Knowing Yangguan, it is all because of Wang Wei's poem; the west out of Yangguan has no reason. Sorrow and sorrow, as if containing infinite desolation in it. Later, after graduating from college, when the last time I met with the window, someone read the poem, and it was a female classmate, her voice was sad, word by word, and the last "person" word had not yet landed, and she burst into tears. Thinking of a school gate, the sea of people is uncertain, the future is uncertain, and a parting cocktail party ends in misery. Therefore, from that moment on, the yang guan of the melancholy was forever fixed in my mind.

However, when autumn comes to spring, Yangguan is still in his dreams, in the sound of the horseshoe of the deceased who regrets farewell...

It's not that I don't want to fold a willow and go thousands of miles to explore the land that the ancients conquered, but I am afraid of my fragile nerves, and I can't bear the camel bell that fades away, and strike out the heavy sigh that the old man yiyi looked back.

But at this moment I was still standing on the ruins of Yangguan, and it was still a crisp autumn morning. The blue sky, like the sea gently washed it over, snow white clouds, like a flying sky in the air scattered a cloud of cotton wool.

However, there is no castle, no arrow tower, no soldiers in military uniforms. Looking at it from the extreme, there is still yellow sand outside the yellow sand, and there is still the Gobi outside the Gobi. But this was once the ancient battlefield of "Hu Tian August is flying snow"! The twenty-three-year-old hussar general Huo Fuyi once fought against the Xiongnu here and captured the "Heavenly Golden Man" of the people on horseback; Zhang Qian and his 300 retinue had set out from Guanxia to Wusun and dredged the thousands of mountains and rivers of the Silk Road; the Western Han general Zhao Baonu, who "did not break the Oath of Loulan and not returned", also drove from here to directly attack the ancient kingdom of Loulan and Cheshi, and the Pavilion was blocked in Jiuquan and Yumen; the general Li Guanglitun of the Second Division, after a year of bloody battles, finally won three thousand sweat and blood horses for the Western Han Dynasty, which made Han Wu ecstatic and the whole country rejoiced. At that time, the banner hunting, the drums of war, the arrows flying like locusts, the soldiers and horses like ants, the Han army destroyed the decay, and tens of thousands of iron horses swept the clouds, so that the Xiongnu who had been plagued for a hundred years were driven out of the Hexi Corridor. The Huns who had lost their armor and fled for their lives had to lament: The loss of my Qilian Mountain has made my six animals restless; the death of my Yanzhi Mountain has left my women colorless. But where have all these spectacular scenes gone? Why is there only desert yellow sand, damaged beacons, wind-eroded Great Wall, and a big Gobi that cannot be seen at a glance. What about war drums? What about smoke? What about the iron army of Ma Ta Fei Yan? Is it really all gone into this barren sea? Could it be that the unbreakable border cities, pavilion barriers, passes, and piers have all become passers-by of history, and have become imaginary relics?

However, the sand is still flying, the wind is still roaring, and the sun's ultraviolet rays are still shooting overhead. What about those Hu and Han people who look at each other, a few people, many hundreds, driving teams of camels, riding horses, carrying bags, carrying silk, and stubbornly running on the Gobi? Those who have stepped on the tranquility of the desert and covered the wind and dust of the plateau have made the court ladies more colorful, once praised by the city as immortals, and once made the ancient Romans and ancient Greeks marvel at the colorful silk, simple and elegant pottery, porcelain? What about those who have crossed the green ridges and waded through the Aral Sea of the Caspian Sea, which have made the royal nobles praise and let the people of the great Han dynasty reminisce endlessly about sesame seeds, alfalfa, walnuts, pomegranates, and grapes? What about those caravanserais, guest houses, and carriages and horse shops that have smoked and waved wine flags, let countless merchants and camel caravans rest their feet and tip their heads, and dream of returning to Chicken Saixi night and night? Was it really stripped, trampled, and flattened by the wind of the Tang Dynasty, the rain of the Song Dynasty, the iron horse of the Yuan Dynasty, the chariots of the Ming Dynasty, and the artillery fire of the Qing people? Why is it that now only this version of the border city, the remaining kiln sites, the faintly recognizable farmland and channels, or even the above and below the ground and the countless copper coins, pottery pieces, wheels, bricks, human bones, animal bones, blades and Han Jian are left? And these are all symbols of our ancient people's load, camping, transmission and as a fusion of Chinese and Western cultures. They have also been brilliant for a while, nourishing families and nations, bringing hope to young women in boudoirs, longing to old mothers who are leaning on the door, and bringing joy to children in dreams. Now they have become a cloud of smoke, buried in the desert, lying in the gravel, letting the eagles in the sky whirl on it, the cold wind of the desert whipping over and over again, and the sand and dust of the Gobi are buried again and again. But who can know how many "people in the spring dream" are looking forward to these weathered pottery pieces and relics, and even unclaimed bones!

Standing on the ruins of Yangguan, looking west at the Gobi, the vast wilderness, endless. The Han sea is no longer the golden yellow we imagined, and the grassland is not the verdant in our minds, they have been blackened by the colorless wind and scorched by the flameless fire. Dark and dull, more than twenty beacons lined up from south to north on the ruins, like undulating waves, like chariots lined up, standing alone on the dunes, although archaeologists surrounded it with a circle of iron bars, but it was still like an old man with a walking stick, standing in an uninhabited place, helplessly looking at the cloudy sky in the west under the scorching sun, not knowing whether it was a memory or a lament. Behind it, Yangguan is disappearing, everything is turning into gravel or turning into sand, only the Qilian Mountains of hundreds of millions of years ago are silently watching it, watching the splendor it has had and the splendor it has disappeared.

Only at this moment, standing on the gravel of Yangguan, I could really read Wang Wei.

October 2008

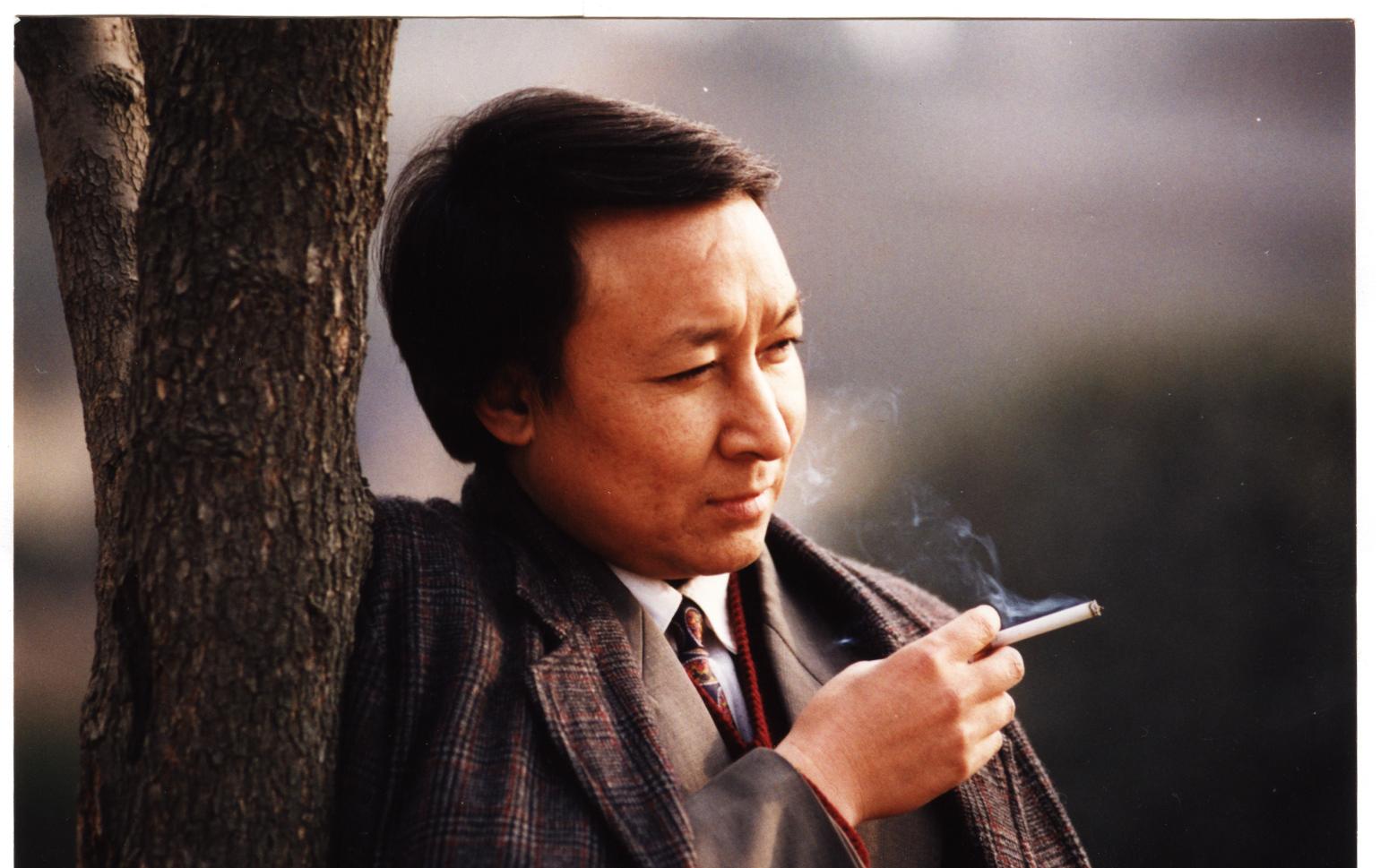

Wang Shenghua, real name Li Chonghua, pen name Mengzhi. Famous writer, critic, calligrapher, and cultural scholar. Graduated from northwestern university Chinese department.

He is a member of the Chinese Writers Association, honorary chairman of the Chinese Calligraphers and Painters Association, vice chairman of the National Joint Conference of Sinology Institutions, member of the Art Committee of the Shaanxi Provincial Committee of the China Democratic League, executive vice chairman of the Shaanxi Provincial Sinology Research Association, visiting professor of Chang'an University, professor of modern college of Northwest University, visiting professor of Xi'an Urban Construction Vocational College, consultant of Shaanxi Folk Writers Association, consultant of Confucius Society of Shaanxi Province, etc. He was the editor-in-chief of Western Art Newspaper and the director of the Joint Department of the Shaanxi Provincial Federation of Literature and Literature. He has published more than 20 works such as "Dream Home" and won 37 national awards.