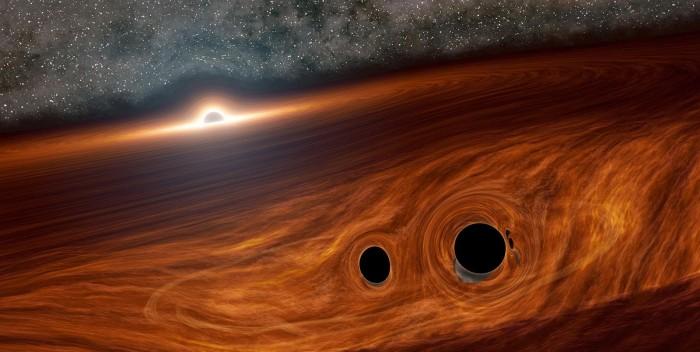

For the first time, astronomers saw the light emitted by the merger of two black holes, providing an opportunity to understand these mysterious dark objects. The artist's concept diagram below shows a supermassive black hole surrounded by a disk of gas. Embedded in this disk are two smaller black holes, which may have merged together to form a new one.

When two black holes rotate against each other and eventually collide, they emit gravitational waves — ripples in space and time that can now be detected with extremely sensitive instruments on Earth. Because black holes and black hole mergers are completely dark, these events are invisible to telescopes and other optical detection instruments used by astronomers. However, theorists have come up with ideas on how black hole mergers can produce light signals by causing radiation from nearby matter.

Now, scientists using the California Institute of Technology's Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) at the Palomar Observatory near San Diego may have found that this could be the case. If confirmed, it would be the first known flare from a colliding pair of black holes.

On May 21, 2019, two gravitational-wave detectors — the National Science Foundation's Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO for short, and Europe's Virgo detector — discovered the merger in an event called GW190521g. The probe allowed ZTF scientists to look for light signals from the source of gravitational waves. These gravitational wave detectors have also found mergers between dense cosmic objects known as neutron stars, and astronomers have identified the light radiation produced by these collisions.