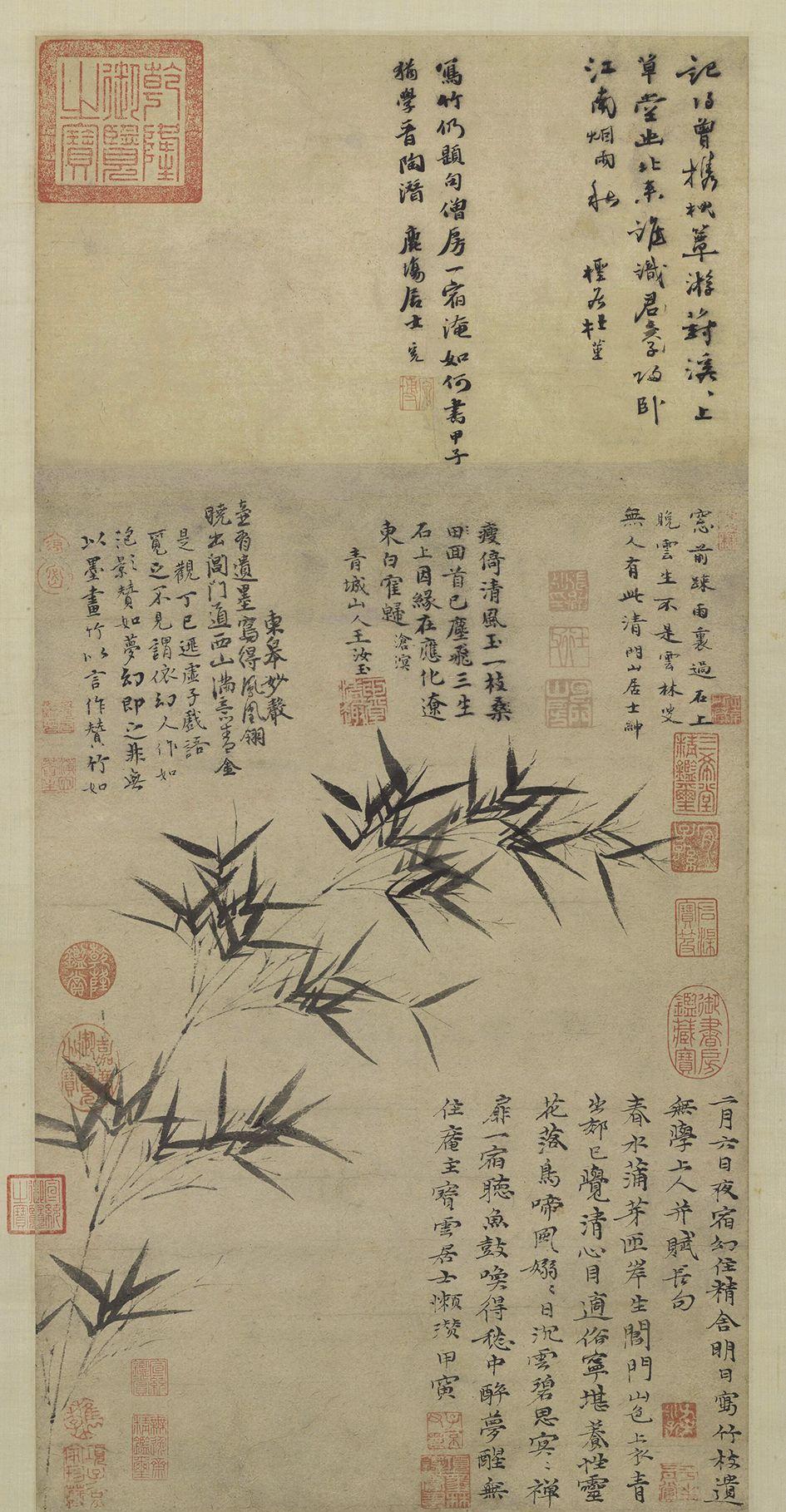

[Yuan] Ni Zhan 《修竹圖》Ink on paper 51cm×34.5cm 1374 Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

"Running Dragon" from the Six Dynasties Period, from the Princeton University Museum

Luoyang unearthed Western Han Dynasty portrait stone carved rubbings "Running Horse"

Whoever he is, as long as he has seen the literati landscape paintings of the 14th century Yuan Dynasty, he will find that he is facing another world that is completely different from the majestic landscape paintings of the early Song Dynasty. What later Chinese paintings show is that as an individual artist, he speaks with words and images full of great enthusiasm and concentration—his voice, to us today, is convincing and resonant, even quite modern. As early as the 14th century, it is truly surprising that the art of painting has such a personalized expression. Describing and trying to explain this phenomenon is the purpose of this book.

Perhaps, no civilization in the world has been so consciously given such an important place in society and culture as in China. Imperial nobles were not only enthusiastic about sponsoring and supporting art, but were often excellent artists themselves. The art of the Royal Hanlin Academy is not only the art of poetry and beauty, but also the art of moral and political ideals—it is based on the Neo-Confucian assertion that "literature carries the Tao", but its additional directive, the "Tao", must be represented by the state.

Another basic principle of Chinese culture holds that "traveling in the arts" is an effective way for a person to cultivate his moral self. In fact, the idea of individualist artists as cultural heroes is taken from the ancient model, that is, the hermit is regarded as the embodiment of the country's Confucian moral conscience. These hermits, in times of political upheaval, were seen as a symbol of resistance to tyranny. Zheng Sixiao, a 13th-century relict literati artist, once described them like this:

If Mr. Yang is in heaven, he still sees his Peugeot, scatters into the breeze, and looks up to Xu You, Boyi, Shuqi, Qu Yuan, and Ziling, and his meaning is far away. The eldest husband can tail and tail behind people. The People of Weis came out, and the future generations all walked under Wei Fu, enough to kill their hearts and serve them.

In China, Confucius was the first to explain the problem of literary and artistic expression: "There is a will to say, words to be sufficient, and words to be sufficient." In contrast, the 5th-century literary critic Liu Xun wrote about the representation of emotional responses in poetry:

Da Shun Yun: Poetry, Song And Verse. According to the analysis of the Holy Scriptures, the righteousness is clear. It is to be in the heart, and to speak is to be poetry.

After the Mongols entered the Central Plains in 1279, the search for expression or "speech" became the primary motivation in painting. In fact, painting after being ruled by foreign peoples has changed so much that it can be regarded as a new art of drawing. If Song painting is based on the reproduction of the objective world as the main purpose, then the yuan painting marks the end of this objective reproduction, the real theme of the yuan painting is the artist's internal reaction to the world in which he lives, in view of the meaning of the subject depicted, because the personal and symbolic connection has become complicated, sometimes only the use of language can express, the painter began to write poems on his paintings. On a meta-painting with an inscription, the meaning of the words and images is further expanded by the use of a calligraphic pen. The multiple relationships between words, images and calligraphy thus form the basis of a new kind of art in which pictures and ideas, figurative and abstract, are integrated.

In the eyes of Chinese, painting is an ideographic symbol that can convey meaning, the so-called "figure load". According to the 5th-century scholar Yan Yanzhi, there are three types of diagrams: the first is "Tuli", that is, the Gua Xiang in the I Ching, which represents the laws of nature; the second is "Tuzhi", that is, or orthography, which represents ideas; and the last is "graphics", that is, painting, which represents the natural image. Whether calligraphy or painting, because the ideographic power of a magical symbol comes from the maker of the symbol, a work of art can be seen both as a trace of the artist's physical movement, or as a representation or metaphor for the dynamic but harmonious balance of the universe. Thus, Chinese painting theory links ideographic practice to the artist's bodily behavior. Calligraphy is not only writing, not only containing literal and literary content, but also gesture and improvisational performance, a tool for conveying natural energy and personal interest. In the same way, painting is functional and real, full of magical power and personal expression.

There are significant differences in the way Chinese and Western paintings are viewed. At first, the Greeks saw art as "imitation", or "imitation of nature", and the goal of Western pictorial reproduction was determined to be the conquest of the appearance of reality and the acquisition of a classical ideal standard of beauty. On the contrary, China's pictorial reproduction and attempt to create are neither realism nor mere ideal forms. Western painters always try to obtain the illusion effect by concealing the medium of painting, but Chinese painters try to use calligraphy with brushes to grasp the spirit behind the shape, the so-called "writing god in shape". To describe Chinese painting, it is necessary to take into account both the specific work and the author's physical and mental condition. When the 5th-century Sheikh first coined the term "qi rhyme vivid" as the first meaning of painting, he used a series of phrases of "qi" to describe the painter and his works, such as "qi", "qi", "qi", "qi", "qi", etc. The 9th-century art historian Zhang Yanyuan wrote that as long as a painter "asks for his paintings with rhyme, he seems to be in between." When the painter and the "qi" of his works arouse the audience's reaction, his paintings will reflect a kind of vitality in addition to the image reproduction.

The key to Chinese painting lies in its calligraphy with a pen. The so-called "traces of pen and ink" means that the essence of calligraphy works is that the pen is the continuation of the calligrapher's own body. Similarly, Chinese painting also reflects the movement of the painter's body. Due to the importance of the artist's personal "traces" or "handwriting" in the work of art, it is of course counterproductive to try to create an illusion by concealing or erasing the media. Chinese artists never merely pursue realism, so they use the symbols of writing and painting to create poems and paintings, which can be read and recited and can be viewed. In the 14th century, the relationship between poetic calligraphy and painting developed to a new stage: they not only complemented each other, but also became one as a form of creative expression, and the elements of words and images grew and perfected each other.

Despite the critical reservations chinese painters had about realism, they did master the technique of illusion in their paintings. After the realism technique reached its peak in the late Song Dynasty, Ni Zhan, who lived in the 14th century, once asked: "Is it better to compare it with its similarity and non-existence... Others consider it hemp or aloe. For Ni Zhan, the bamboo he painted, although it may look like a stalk or a reed, is represented by bamboo when it is perceived to be real, when it reaches a point of dissimilarity and transcends reproduction. Because Chinese painters have never developed scientific anatomical, chiaroscuro, or perspective methods, they have no reason to oppose reproduction, and thus do not need to create a non-figurative art.

Early Chinese pictorial reproduction was initially also concerned with "shape-likeness", that is, the formal similarity of images to what the eye sees in reality. There is a tile rubbing of portraits from a Han Dynasty tomb in Luoyang depicting a Tengyue horse from the 3rd century BC. The "resemblance" of this horse shows that its drawing is based on observations of nature. However, the poems of the ancient Chinese who recorded horses tell us that the image of this horse is actually not just a visual record of what the painter saw.

In the Han Dynasty, visiting foreign dignitaries often presented the Divine Horse (then called Tianma, or Dragon) from Dawan (Ferhana) as a tribute to the Chinese emperor. They were taller and stronger than the Mongol horses of North China, and these precious war horses, with narrow heads, wide eyes, wide noses, and strong necks, were described as having supernatural qualities, such as sweating like blood and traveling thousands of miles a day. Thus, in a Chinese painting, a superior horse is understood as a supernatural dragon horse.

Here is another monster of the Six Dynasties, "Ben Long": in the picture, the Ben Dragon has a large mouth, a bowed body, a high tail, and a stride with its head held high, echoing the dragon horse of the Han Dynasty. Both the horse and the dragon are shaped by rounded shapes and flowing curves, which have a circling and twisting effect in space. The beautiful lines of Han Dynasty brick paintings, which are strong and strong, thick and thin, create a smooth and compact animal image, showing its speed and movement. In order to depict that kind of heavenly dragon horse, the artist conceived of a dragon-like form, which is actually a supernatural divine beast.

This close similarity between images of horses and images of dragons reveals a truth in artistic representation: the artist's work comes neither from life nor from imagination. On the one hand, they rely on schemas to transform visual images into pictures or sculptures; on the other hand, they follow the inherent meanings associated with imagination culturally. In his book Art and Illusion: A Psychological Study of Pictorial Reproduction, E.H. Gombrich defines the artist's work as "making first and then matching", through a process of "schema and correction". Drawing on the theories of Emanuel Lowe, a researcher of ancient Greek art, Gundell summarized the problem of natural representation in art as follows: "Paleo-style art begins with schemas, that is, only from one angle to outline symmetrical positive figures; the success of naturalism can be seen as the accumulation of gradual revision of schemas due to the observation of reality." "Once created, the image of the Tengyue horse in ancient Chinese painting became a basic pattern that was followed by later Generations of Chinese artists, and all they could do about it was some gradual changes. This realistic reproduction method gradually perfected, reaching its peak in the Song Dynasty, until after the Yuan Dynasty, with the emphasis on calligraphy and superficial abstraction, it returned to symbolic expression.

The development of early Chinese figure painting, from the Han Dynasty in the 3rd century BC to the Tang Dynasty in the 8th century, is similar to the so-called "Greek miracle" or "Greek revolution", and the figure shape awakens from the dull ancient style of positive law and becomes an organically connected image that can move freely in space. Landscape painting, from the Han Dynasty to the end of the Song Dynasty, that is, the reproduction of the motif of the mountain tree in the late 13th century, developed into an illusionary spatial creation: using perspective shortening, a single piece of ground is in a spatial retreat.

Taking place at the end of the 13th and early 14th centuries, the transformation of Chinese painting from realistic reproduction to symbolic self-expression was both a product and a tool of change in the history of Chinese society and culture. In the Tang Dynasty, the aristocratic ruling class was cosmopolitan in its vision; the narrative art of the Tang Dynasty, which served the needs of state etiquette and indoctrination, expressed the luxurious world of emperors and military generals. In the early Northern Song Dynasty, with the rise of the literati and the powerful Neo-Confucian movement, painters shifted from the narrative of human history to the vast and boundless natural world. This macroscopic view of the natural universe of the Northern Song Dynasty arrived in the Southern Song Dynasty and was replaced by an era of reflection in painting. Painters of the time turned inward, using flowers and trees as symbols of revealing spiritual pictures. In the Yuan Dynasty, this symbolic self-expression trend became more popular with the mongols' accession to the throne. When realistic natural reproductions gave way to symbolic images of lone trees, bamboo stones, and flowers, painting became equivalent to calligraphy. However, when the image carries too many symbolic meanings, it is no longer understandable without the help of language. Literati painters of the Yuan Dynasty created a set of discourses, a context, by inscribing poems on paintings, using words and images.

Although the calligraphic style flourished after the Mongols entered the Central Plains, it was deeply rooted in the art of literati and doctors in the late 11th century of the Northern Song Dynasty. It was a period of political and moral crisis, and the art of painting and calligraphy was increasingly under the control of the imperial court. These literati doctors, the intellectual elite of Song Dynasty China, broke away from official orthodoxy and created a new type of scholar-doctor painting art, that is, the predecessor of the literati painting of the Yuan Dynasty. Scholars and artists of the late Northern Song Dynasty, such as Su Shi, Li Gonglin and Mi Fu, who were unparalleled geniuses, retired from politics and lived a Thoreau-style life of seclusion. They often converted to the ancient mystical Taoist philosophy or Buddhism introduced from India. The "Tao" that Confucians hold as a moral code is the way of nature in Taoism and Buddhism—inaction, freedom, and going with the flow. The literati and amateur painters changed the decorative public style used by professional painters, and sought a kind of self-transcendence by creating personalized styles. Drawing on the resources of antiquity, they simplify and purify the technical elements of their works—the decoration of colors and the realism of imitation. In this way, as poets, calligraphers and painters, they are reunited with the Way of the Universe. They exalted the simplicity of antiquity as a means of innovation, which, although they suffered political failures, gave them brilliant success in their artistic pursuits.

From the end of the Northern Song Dynasty onwards, Chinese literati and artists used the contemplation of past history and the summation of historical lessons as a fruitful strategy for triggering drastic reforms and stylistic innovations. Going back to the past doesn't mean imitating the past, it's the opposite. Because only by immersing himself in learning the past, grasping its truth from the surface and the inside, can the artist re-integrate himself with nature and the past. He wants to reinvent himself in this way.

Perhaps, the essential difference between Chinese and Western painting does not lie in the difference in the artist's understanding of the past tradition, but in the difference in the historical application of the past tradition. The term "classicism" in Western art history has its roots in idealism and refers to several eras of artistic revival inspired by ancient Greco-Roman and Greco-Roman ideals, notably Renaissance Italy and France in the 17th and 18th centuries. In the history of Western art, classicism is followed by anti-classicism (such as the Gothic, Baroque, and Romantic periods), which have been seen as an era of decline. However, in the history of Chinese art, there is no period in ancient times that represents a normative classical standard, and although the style of describing antiquity has been ubiquitous for thousands of years, there is no specific era that can be said to be more classical than other eras.

In the history of Western art, precisely because classicism is guided by values based on order and structure, there is a hypothetical ideological connection between classicism and legitimacy and power. On the contrary, as the antithesis of official retrofuturism, the "ancient meaning" of Chinese artists is clearly based on individuality and psychology. When contemplating and commenting on a quotation or an early landscape painting tradition or genre, the artist often arbitrarily rewrites or changes its contents to express his new meaning, placing retrofuturism in the context of the idealized "ancient" and the unsatisfactory "present", then what it represents is not so much a set of standards as a desire and defense for change. In the works of calligraphy and painting, we can see the interconnection between ancient style, personal psychological reactions and social behavior. According to his own temperament, an artist will choose a certain antique genre and create his own expressive style. Thus, contrary to Western classicism, Chinese retrofuturism is able to satisfy both apparent conflicts of opposites: reconstructing ancient styles as their own, individual expressions. Paradoxically, it takes into account both orthodoxy and heresy, tradition and innovation.

After the establishment of the Mongol Yuan Dynasty, literati artists turned to their hearts as they tried to escape political and social turmoil. Literati painting is not mainly a manifestation of the times, but an individual's reflection and struggle against the decline and decline of life. From the revival of Yuan Dynasty art, we see the efforts made by artists to reposition and rediscover individual identity. Contrary to the Western view of progressive history, the circular view of history Chinese offered the literati painters of the Yuan Dynasty the possibility of restoring the harmonious unity of antiquity and creating continuity beyond change.

(This article is an introduction to the book Beyond Reproduction: Chinese Painting and Calligraphy from the 8th to the 14th Centuries, by the famous art historian Fang Wen, Zhejiang University Press, May 2011, translated by Li Weikun.) )

<h1 toutiao-origin="h4" > Editor: Liu Zhilin</h1>