John Robbie (Gary Grant) is a habitual thief who stole in France before the war. His technique is so characteristic that every crime he commits has left his mark, and he has been called a "black cat". After falling into the net and being sent to prison, Robbie manages to escape by accidentally blowing up the prison. He later joined the underground and eventually became a hero of the French Resistance.

The film begins years later, when Robbie has retreated to a country house in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, enjoying the comforts of his previous career. Yet his quiet life was shattered by a series of jewelry thefts at riviera mansions and hotels, and thieves were clearly connoisseurs like him and with the same style.

He was called into doubt, and his retirement and daily habits were disrupted. The former "Black Cat" therefore decided that the only way to regain his tranquility was to expose the thief who had plagiarized him by the police. To track down his imitators, he used the dialectic that Arsène Lupin could not have done otherwise: "To expose the new black cat, I must catch him the next time he steals; and to analyze who he will attack next (because he thinks from my point of view), I just have to imagine what I would do if I did his theft, Or imagine from his point of view what I'm going to do next. In fact, that is, from my own point of view. Apparently, Robbie succeeded.

I present you here in detail the storyline of To Catch a Thief (1955) to show that, regardless of appearance, Hitchcock remains faithful to his eternal themes: interchangeability, reversal of crime, moral and even behavioral identity between two men.

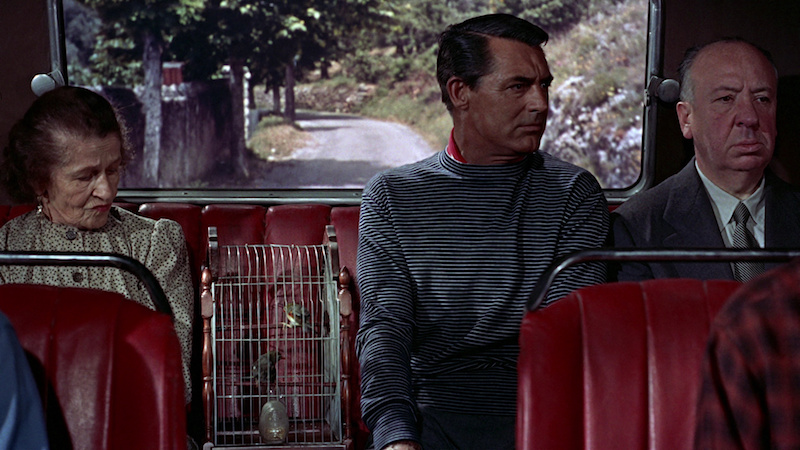

Without revealing the plot of To Catch a Thief, I'm pretty sure brigitte auber and Grant are so similar and both wear the same striped shirts — Grant's blue and white stripes, Aubert's red and white stripes – it's no coincidence. Grant's hair splits on the right, while Auber's is on the left. They are similar in appearance and opposed at the same time, so that the film has a symmetry from beginning to end, a kind of confrontation that is also presented in the smallest details of the plot.

"To Catch a Thief" is not a black-and-white film, and there are not many elements of suspense. Its framework is different from that of I Confess (1953) and Strangers on a Train (1951), but its basic architecture is the same, and the relationships between the characters are the same.

I mentioned Arthur Robbin earlier because this new Hitchcock film is so elegant, witty, and almost emotionally sad, and somewhat similar to the approach of The Enigma of 813 (813, 1910) and l'aiguille creuse (1909). Sure, it's a crime story meant to make us laugh, but Hitchcock's basic idea still moves him toward the model of Jacques Becker's Touchez pas au Grisbi (1954): thieves are ultimately exhausted. Gary Grant is the protagonist of the film, disillusioned, and his life is over. And this last vote forced him to use all the tricks of a thief for the request of a policeman, and brought him a sense of nostalgia for returning to the industry. You might be surprised that I saw To Catch a Thief as a pessimistic movie, but all you have to do is listen to the melancholy soundtrack of Georgie Auld and Lyn Murray, and then check out Grant's extraordinary performance (you get it).

Like Dial m for Murder (1954) and Rear Window (1954), Hitchcock's use of Grace Kelly was crucial: here she played an extraordinary American, Mary Shantar, who eventually became the only one to catch grant by marrying him.

I've read people who criticize To Catch a Thief for not being realistic enough. But André Bazin points out the nature of Hitchcock's relationship with realism:

Hitchcock never deceived his audience, and whether it was pure dramatic appeal or deep suffering, our curiosity was not driven by a vague threat. It's not a question of the mysterious atmosphere of a perilous situation emerging from the shadows, but a question of non-equilibrium: like a huge block of iron sliding down a smooth slope, we can easily calculate how it will accelerate. The director's direction thus becomes an art, pointing out where reality lies when the vertical line of the dramatic center of gravity is about to leave its supporting polyhedra. Such a directorial style abandons the impact of the opening and the collision at the end. For me, I can see in this wonderfully unbalanced and decisive level the core of Hitchcock's style, which is so personal that we can see through it at a glance in his most ordinary shots.

In order to maintain the imbalance of creating a tense atmosphere in the film at all times, Hitchcock obviously had to sacrifice many of the essential shots in psychological films (links, revelations, climaxes), and he apparently had no interest in shooting them. He has always tended to ignore realism and even despise rationality in his suspenseful stories, especially as audiences of an entire era have identified only with "historical ... Sociologically... Psychologically "reasonable plot.

Alfred Hitchcock, like Renoir, Rossellini, Orson Welles, and other great filmmakers, believed that psychology was the least thing to worry about. The master of suspense's realization of realism is accomplished through a high degree of loyalty to the precision and accuracy of its effects in the most unlikely scenes. In To Catch a Thief, there are three or four unreal scenes that jump to the audience, but the precision in each shot has never been seen before.

Here's an entry in the archives: After Hitchcock returned to Hollywood to shoot the studio scene for To Catch a Thief, his assistants stayed in France to shoot the Riviera's "feature film." He then sent a telegram from Hollywood to his assistant in Nice, asking him to remake a scene that would only last on the screen for a maximum of two or three seconds, and the telegram read:

Dear Hebby: I've seen the scene where the car dodged the oncoming bus. I'm afraid it won't work, for the following reason: As our cameras turned, the bus appeared so suddenly that it passed before the danger could appear. Two areas that need to be corrected: First: move on the straight and show that there is a curve at the end so that we know it exists before we reach the corner. When we arrived, we should have been surprised to see the bus appear and greet us. Because the corners are narrow, the bus should be on the left, and our cameras should never go straight into the corners. Second: In this shot projected, the bus appears only halfway. I realized it was because you were cornering. To correct this error, you can install the camera on the left side so that when the bus turns, the camera can slide from the left side to the right side. The rest of the shots are breathtakingly beautiful. Greetings to the entire crew. Hitchland.

In the career of a man who knows better than anyone what he wants and how to get it, To Catch a Thief may be a trivial film, but it still satisfies his fans—the most snobbish and ordinary—and still becomes one of the most cynical films Hitchcock has ever made. The last scene between Grant and Kelly is a classic. This fantastic film updates Hitchcock's label and witnesses that he remains as he always has been. It's a humorous, funny film, and its teasing of French police officers and American tourists is also mischievous.

——1955

《捉贼记》(to catch a thief,1955)

Translation: Stalker @ Shadow Translation