【Text/Martin Wolfe Translation/Observer Network by Guan Qun】

What commitments must be made at the twenty-sixth meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, held in Glasgow, if the increase in surface temperatures is to be kept to the extent possible, as recommended by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, as recommended by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change? As I said last week, the answer is that they have to be more aggressive: most importantly, they need to cut more.

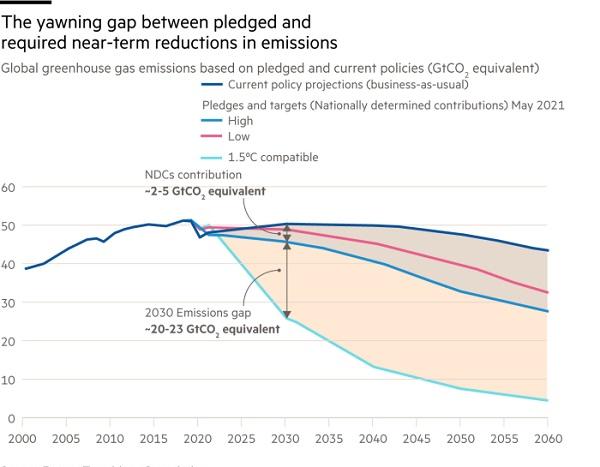

Promises like "net zero energy" in thirty years are all too easy to deliver on. It is now necessary to commit to reducing global carbon emissions by almost 40% by 2030. The emission curve must now be bent downwards. Despite the difficulties, this is both economically and technically feasible. Without the high-risk geoengineering that Gernot Wagner recently discussed, the planet will inevitably suffer irreversible damage 10 years from now.

So, what must be done now? A book published last month solves this problem. The book proposes a six-point plan to provide a reference standard for discussion at the Glasgow conference.

The plan includes: first, a substantial and rapid reduction in methane emissions, which is an extremely potent greenhouse gas despite its relatively short duration in the atmosphere; second, to stop deforestation and restart afforestation; third, to decarbonize the power sector and, most importantly, to gradually free it from coal at a much faster pace than it is now; fourth, to speed up the electrification of road transport; and fifth, to "decarbonize" heating and steel, cement, chemicals, long-haul air shipping, and so on. The industry needs to accelerate decarbonization; finally, accelerate energy efficiency across the economy, especially new buildings, and renovate many older buildings.

The plan makes it clear that much of the work will be complex and difficult to do. However, appropriate support in terms of incentives, regulation, greater transparency, encouraging the investment of necessary financial resources and providing generous assistance to emerging and developing countries is possible.

Consider what this ambitious plan will actually mean for the next decade. One point is particularly clear: the Nationally Assigned Contribution Plan needs to be more rigorous and detailed. Another point is that the most important emerging countries – first China, then India and Indonesia – need to commit not to building new coal-fired power stations from now on.

Another point is that stopping deforestation and starting to stop using coal, especially for electricity, will require a steady stream of aid and subsidies from high-income countries to developing countries, which could amount to around $100 billion a year. This is crucial if an agreement is to be reached. But it's also fair and reasonable, because high-income countries have emitted the most carbon in the past, and until now their per capita carbon emissions have remained relatively high.

The gap between committed emissions reductions and the required emissions Reductions Image: Financial Times

Developed countries must also provide financial support to developing countries to help them build environmentally friendly power systems. Equity capital and debt financing methods are too costly and have limited utility. A key element is the risk-sharing between the private and global public sectors. Multilateral development banks must play a central role. Adair Turner, co-chair of the Energy Transitions Commission, said the money needed could be $300 billion a year and would rise to $600 billion by the end of the century.

Another point is to strengthen the effectiveness of international agreements to accelerate the net zero process of the above-mentioned "difficult to decarbonize" industries. The EU's proposed Carbon Boundary Adjustment Measures are a key element in achieving net zero.

Finally, achieving electrification is central. If there is no better option, electricity can be supplied in a carbon-neutral manner, including nuclear energy.

In short, these things need to be done to meet the goal of drastic emissions reductions by 2030. More broadly, however, negotiators also need to remember three things.

How to keep the temperature rising within 1.5 degrees Celsius Image: Financial Times

First, the price mechanism is more than just an effective incentive mechanism. It can also generate income to compensate the damaged. However, as the World Bank's Carbon Pricing Matrix indicates, carbon prices are generally too low and coverage is limited.

Second, policymakers must remember that no matter what changes occur, the premise is that the lights cannot be extinguished and the house cannot be cold.

In the end, we really came together. While China, the United States, the European Union, India, and Japan will be key, no single country can solve the problem alone. Individual countries will explore viable paths. But an agreement must be reached, especially between China and the United States. As the Prime Minister of Bangladesh pointed out in an article in the Financial Times, rich countries must help poor countries.

Technical experts have done an excellent job of demonstrating our ability to decarbonize our economies as quickly as possible. Now, leaders must show that they understand what this means. Act quickly, and that's how to avoid disaster.

(The Observer Network is translated by Guan Qun from the Financial Times)

This article is the exclusive manuscript of the observer network, the content of the article is purely the author's personal views, does not represent the platform views, unauthorized, may not be reproduced, otherwise will be investigated for legal responsibility. Pay attention to the observer network WeChat guanchacn, read interesting articles every day.