Brodsky Figure/IC

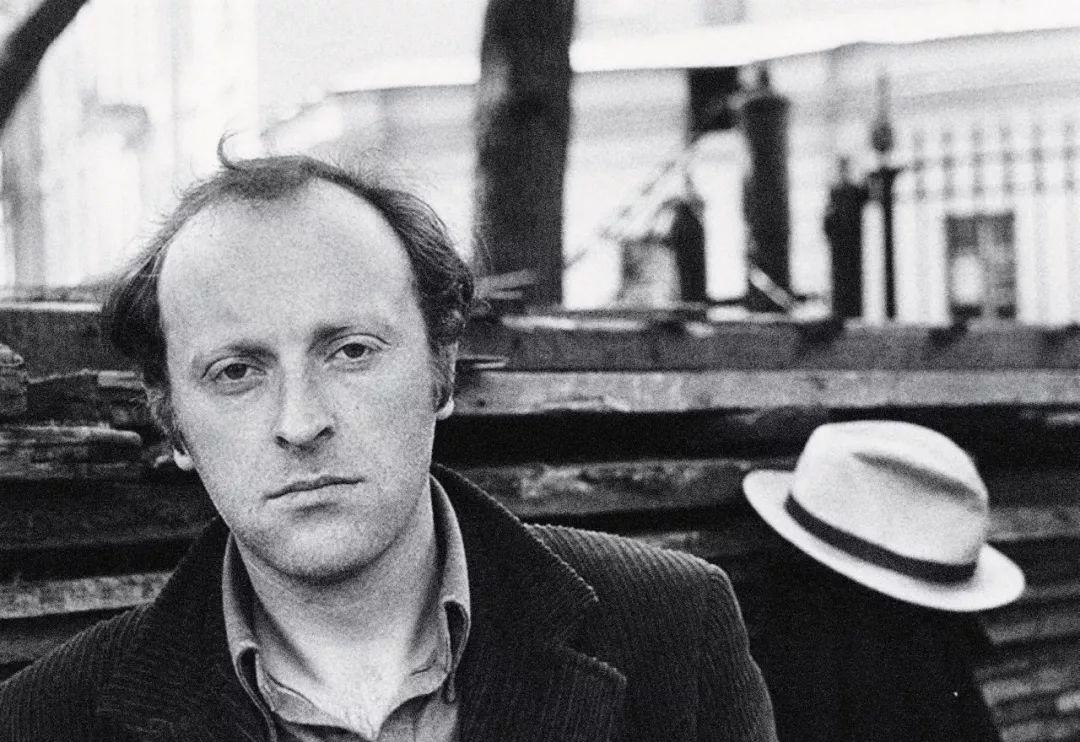

Brodsky: Poetry comes from Providence

Reporter/Liu Yuanhang

Published in China News Weekly on July 29, 2019, Issue 909

In 1970, the Russian-American novelist Nabokov, after reading a long poem by a young Soviet poet, sent him a pair of jeans, which was still scarce in the Soviet Union at that time. Solzhenitsyn, a writer in exile, once said that as long as it was the poet's work published in a Russian-language journal, he would never miss it. The English philosopher Isaiah Berlin described it as a genius when one reads the poet's work.

The poet's name was Joseph Brodsky. A Soviet-born poet, an exile who had been wandering for half his life, a Jew, wrote in both Russian and English, and won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1987. Since the 1990s, he has also had a considerable influence on China's intellectuals and writers.

In April this year, the first volume (volume I) of Brodsky's Complete Poetry was introduced and published by the Shanghai Translation Publishing House, and the translator was Lou Ziliang. This is the third translation of the complete works in the world after English and Russian. After several rounds of discussion, the publisher finally decided to select an annotated edition of the scholarly commentary edited by Brodsky research expert Lev Lochev, with a seventy-thousand-word literary biography as the preface.

"Judging from the acceptance of domestic readers, most people have read his prose and react well, but they don't know much about his poetry, which is a very regrettable thing, and this gap is very necessary to fill in." Liu Chen, the editor-in-charge of The Complete Works of Brodsky's Poetry, told China Newsweek.

Brodsky's poetry has different faces in different cultural contexts, and often cannot be separated from the times and politics, and those verses are like mirrors, reflecting a world full of differences.

"Cross" and "Glass"

The translator Lou Ziliang is 87 years old, and when he is free, he still smokes and drinks. Previously, his most important translation was Tolstoy's War and Peace, and six years before Brodsky's complete collection of poems was laid out, a new "war" began. He became a wounded soldier at one point, was diagnosed with cancer in the hospital, and fortunately, he recovered well. He picked up his pen and threw himself back into the battlefield.

Sometimes, Lou Ziliang will also work until the middle of the night, feel tired, just take a break, play mahjong for half a day. Now, the dictionary that assists the translation at hand has been turned over. His eyes had also gone wrong, replaced with an intraocular lens, and if the words were too small, they needed a magnifying glass. At night, three or four lights turn on at the same time, and the table is bright, as if performing a difficult internal surgery.

The most important thing is precision, especially for such a complex translation object as Brodsky. "Many people may think that poetry is more important, but it is not. Brodsky's poems, in particular, are often thousands of miles away." Editor-in-charge Liu Chen told China News Weekly. The seventy-thousand-word literary biography was revised three times before and after, and this did not take into account some minor repairs. Brodsky's poetry involves a great deal of philosophical and historical knowledge, as well as the influence of metaphysical poetry.

While translating the long narrative poem "Gorbunov and Gorchakov", Lou Ziliang noticed the confrontation between two voices, which originated from the same consciousness and were anthropomorphized. When encountering obscure places, we still grasp the main points and use the internal context of opposites to determine the specific connotation.

Cultural differences are also prone to ambiguity. In addition, care needs to be taken into account of the intrinsic relationships between the different titles, as well as the unity between the editor's preface, the original text of the poem, and the commentary. Lou Ziliang gives an example of a poem by Brodsky in which a cross and a glass appear, both of which have specific meanings. The cross refers to a cross-shaped prison, and the glass refers to a cell with a small space. The explanation is already given in the comments section, so it can only be translated literally.

Prisons and cells bear witness to Brodsky's hardest experience. In the early '60s, he was arrested three times, "three times to let the knife scrape my nature," was put in a mental hospital, woken up in the middle of the night, and then dipped into a cold shower. Eventually, Brodsky was convicted of "parasites" and exiled to the north of the Soviet Union. The 1964 trial, which has since been frequently mentioned, still shows the conflict between the system and the individual.

At that time, the pockets of public opinion were loosened, and even Solzhenitsyn's A Day in ivan Denisovich had the opportunity to be published, a novel about life in the stalinist labor camps. However, the liberalized political climate was soon replaced by a tightening ideology. During that time, Brodsky had no fixed job and lived by writing poetry and translating. According to the court, he changed jobs 13 times, sometimes for more than half a year.

Brodsky leaned against the wall, and the judge questioned him why he had rested so long and not participated in productive labor. Brodsky replied that he was working, and that poetry writing and translation was his job. None of you had a high school education, and the judge went on to ask, who admits you're a poet? Brodsky replied that schools could not teach a person to be a poet. Where does that poem come from? The judge did not give up. I think Brodsky gave the answer, and it came from Providence.

Eventually, Brodsky had to be exiled from what is now St. Petersburg to a village near the Arctic Ocean for five years of voluntary labor. However, under the mediation of celebrities such as the female poet Akhmatova, the final period of labor reform was reduced to 18 months. Brodsky's popularity in the West grew dramatically, and many see his experience as another testament to pasternak's post-Soviet repressive policies.

Brotz did not want to be portrayed as a victim of the system, but consciously or unconsciously, his poetry and life were always associated with politics.

watermark

By all accounts, Lou Zilian was eight years older than Brodsky. When Brodsky was exiled to the north of the Soviet Union, Lou Ziliang, who was classified as a "rightist," had resigned from a middle school in Shihezi, Xinjiang, and returned to Shanghai alone, becoming an unemployed vagrant, spending all day in the library, reading foreign books, and later finding a job, working in a factory during the day and continuing to read at night. By 1969, he was framed as a "counter-revolutionary" and spent three years in prison, engaged in manual labor.

Lou Ziliang did not quite agree with Brodsky's political leanings, but in terms of self-education, the two people had a lot in common. After coming out of prison, Lou Ziliang still refused to leave the Russian language. At that time, Soviet things were still taboo, and Lou Ziliang read Russian translations of German philosophy, including Marx and Hegel. Self-education is not just about self-taught, Lou Ziliang told China News Weekly, which means you need to set your own direction and choose teaching materials.

Brodsky's experience is equally rare, as he dropped out of school at the age of 15 but became self-taught and became proficient in English and Polish, and later was able to read Latin and French in dictionaries and even learn Chinese. He is surrounded by many professionals, including linguists, musicians, and literary scholars. He escaped from the official Soviet education system and, in the language of poetry, rebuilt his cultural identity and spiritual possessions.

After leaving the Soviet Union, Brodsky traveled to many places and was always looking for his spiritual home. His favorite places are not Ann Arbor and New York in the United States, but Venice in Italy.

Journalist Charles Feniweg recorded his brief dealings with Brodsky in the water city of Venice. It was in 1978, and Brodsky had just finished a recitation in a dilapidated cinema, and with about 20 admirers, he had come to a nearby flyhouse for dinner, where several small tables were put together and turned into squares.

Brodsky invited Fenivich to sit next to him because the journalist's face resembled that of a friend of Brodsky's, who lived in Leningrad, now St. Petersburg, and was a violinist. Six years ago, Brodsky was deported, left the Soviet Union, and settled in the United States.

One of those present asked Brodsky about his 18-month labor camp, describing the frozen soil, swamps and peculiar light, as well as Stalin's joyful and eerie smile and the pomp and circumstance of the Moscow government's funeral. After the dinner, Brodsky and Feniveh proposed to go for a walk outside and talk as they walked. Sometimes Brodsky speaks Russian and then quickly translates into English. Sometimes, he seemed to be talking to himself.

Brodsky loved the Venetian winter, and the great poet Dante had been in exile for many years, staying in Venice for a long time, and Brodsky felt like he was at home, even though he didn't speak Italian. It's one of the few places where he feels at ease, having been here 17 times before and often for Christmas.

In this Eden-like city, he saw "the time born from the water." Life abroad was miserable, but Brodsky did not like the complaints of the exiles around him who were in the same situation. Ten years later, Brodsky published Watermark, a collection of essays on the subject of Venice. Twenty years later, he was buried in the water city.

Scattered reflections

Brodsky won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1987, when he was just 47 years old. His poems began to appear in Soviet publications. At that time, Soviet society had shown signs of relaxation, many previously banned writers had surfaced, and some exiled writers had chosen to return home.

At the same time, Brodsky was translated into China. The translator Sun Yue was one of the first to translate Brodsky, and at that time there was no news of the award in China, Sun Yue borrowed a copy of Brodsky's Russian poetry published in the United States from the National Library, translated several poems, and published them in Contemporary Soviet Literature.

"I personally feel that Brodsky's poetry has had an impact in the West, not mainly because of the Russian language, but because of the English language, and his political overtones. He later went to the West. In the Soviet Union, the controversy was mainly caused by Brodsky's writing skills and writing style, as well as the values inside, which many people did not know about. Sun Yue told China News Weekly.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, many people had expectations for returning diaspora writers, including Brodsky. In the Language Department of Moscow State University, there is more than one teacher who studies Brodsky, and Brodsky's topics are also included in the study and discussion class.

Among the intellectual community, however, attitudes toward Brodsky remain somewhat divisive. The poet Kuberanovsky returned to Moscow in exile in Europe in the early 1980s, on the eve of the collapse of the Soviet Union. He agreed that Brodsky was an outlier among Russian poets, considered one of the most Latinized Russian-speaking authors, but unlike many Russian poets influenced by the European poetic tradition.

The impression was that Brodsky was always busy, always surrounded by people, and he needed these things, like a drug addiction. But on the other hand, Brodsky often felt depressed and tried to escape from the public eye. He traveled the world, incorporating those insights into his own creations, and Kuberanovsky said in an interview that frequent travels showed signs of self-repetition in Brodsky's later creations.

In addition, politics distinguishes one group from another. Kuberanovsky mentioned that when the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968, Brodsky, like many intellectuals, considered it immoral. But by the mid-1990s, when NATO was sending troops to southern Europe, Brodsky's attitude had changed, and Kuberanovsky did not understand and asked Brodsky why he was like this.

"His work was so popular in the 90s that everyone thought he was at the pinnacle of Russian poetry. But in fact, I don't think he loves Russia, he's not a patriot. It should be said that later his attitude towards Russia was very cold. Kuberanovsky told China News Weekly.

In the United States, Brodsky's English creations are highly accepted. He became America's Poet Laureate in 1991, frequently invited to speak, and his commentaries and essays are considered exemplars of English prose, with Less Than One winning the National Book Review Award and Grief and Reason becoming a classic.

Since the 1990s, Brodsky's influence in China has been equally far-reaching. In the 1990s, when various value systems were reshuffled, the intellectual community introduced Brodsky as a confidant. In his poetic theories and essays, he elevated the status of poetry to the height of civilization, and re-refreshed many people's understanding of poetic language. He is believed to have inherited the mantle of the Russian Silver Age, and at the same time people see in him a response to and continuation of the European and American poetic tradition.

The poet Xidu experienced the idealistic 80s, and at the beginning, he regarded Brodsky as a cultural hero, because he had done various jobs such as corpse workers and expedition members, and he had been in exile for many years, trying to maintain the dignity of poetry and life in the turbulent displacement.

When the poet Zang Di read Brodsky's poems, he found in him a valuable quality, that is, "how to gain reason in an ill-fated era." Brodsky felt that Brodsky had a very clear power to break the boundaries between ancient and modern literature, and that the spirit of life and the sense of destiny were fascinating.