This article is reproduced from | China Biotechnology Network

WeChat | biotech-china

We always seem to "not want to grow up". As primates with the strongest brains, modern humans usually follow a "slow" life history (the rhythm of the entire life cycle), for example: we wean ours very early, but it takes a long time for the body and brain to develop into adulthood before we begin to enter the reproductive stage of life.

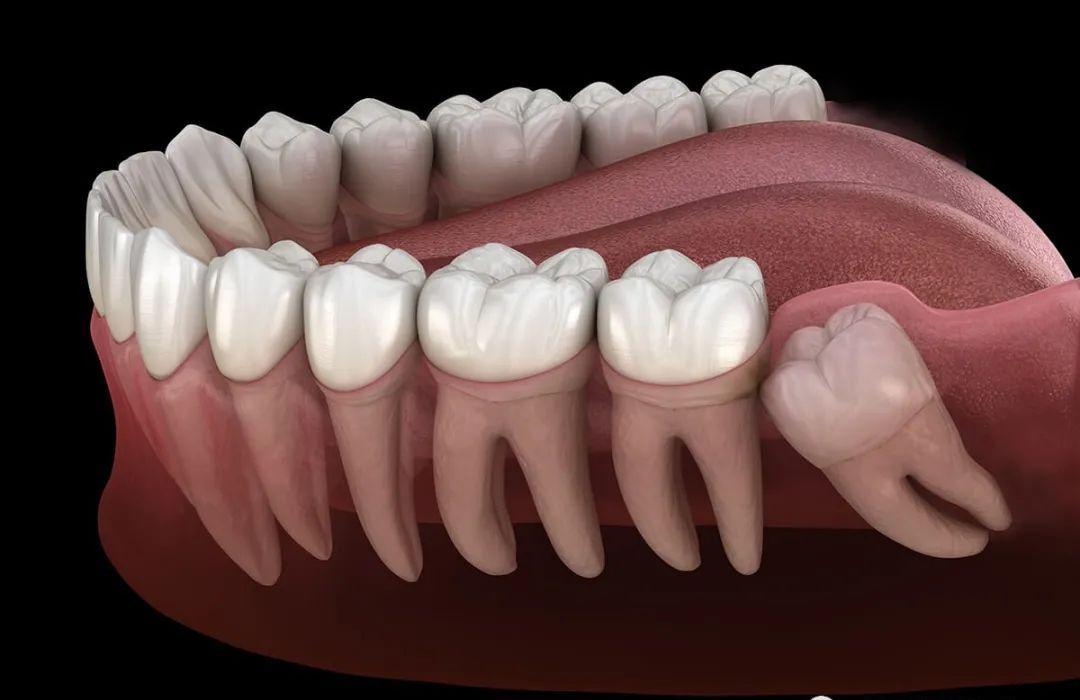

Among human relatives, only chimpanzees extend their time during critical developmental periods, as we do. But even chimpanzees have grown their teeth early. Modern Homo sapiens do not begin to germinate a third molar until the end of puberty, that is, impacted wisdom teeth (commonly known as wisdom teeth). Healthy wisdom teeth can help with chewing, but problematic wisdom teeth can cause inflammation and infection of the gum tissue, ultimately leading to pericoronitis. Therefore, many people have to remove problematic wisdom teeth.

Molars (commonly known as molars) play a vital role in tracking human evolution, and it can be used to determine the age of an individual organism or its remains. But there are still many unanswered questions about molars, such as why they germinate so late in the future wisdom teeth.

Recently, in a study published in Science Advances, researchers from the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University in the United States have proposed one of the mysteries of human biological development - how the precise synchronization between the appearance of molars and life history occurs, and how it is regulated.

Aspects of human life history (the rhythm of the entire life cycle), while unique, are closely integrated with other components of the biology of an organism. For example, throughout mammals, the rhythm of life history is closely linked to patterns and rates of tooth development. The rate at which primates develop teeth, particularly the age at which the first constant molars erupt into the mouth, is closely related to a range of life histories, such as weaning age, age of first reproduction, shortened birth spacing, and mortality. The appearance of molars is often considered the best skeletal indicator of life history and is therefore used to infer the life history attributes of fossil taxa.

For the study, the researchers created 3D biomechanical models of the skulls and teeth of 21 primates, from lemurs to gorillas, and simulated the attachment position of each major masticatory muscle throughout the growth of these species.

The researchers found that the timing of the eruption of adult molars has a lot to do with the delicate balance of biomechanics in our developing skulls.

The mature teeth we use to grind food into a paste usually erupt from the mouth in three stages, that is, around the age of 6, 12 and 18.

The adult molars of other primates grow earlier. Like humanity's close relatives, Pan troglodytes, they develop molars at the age of 3, 6 and 12. Papio cynocephalus had the last adult molars at the age of 7, while macaca mulatta had all teeth by the age of 6.

An important factor that limits the timing of tooth eruption is space. If the jaw is not large enough to fit the full set of adult teeth, there is no need to stuff them all in.

The oral space of early humans was not as large as it is now, and obstructed wisdom teeth (commonly known as wisdom teeth) were a major problem we humans faced. But that doesn't explain why they appear so late in our lives, or why the wisdom teeth in the back always seem to be causing trouble.

Having an empty slot for teeth to grow doesn't mean it's a good idea to put it there, though. Teeth don't chew on their own and require a lot of muscle and bone to support them to ensure enough pressure to grind food safely.

And the reason behind our tooth growth retardation seems to be for "safety".

Study corresponding author Gary Schwartz, a paleoanthropologist at Arizona State University's Institute of Human Origins, said: "It turns out that our jaws develop very slowly, which may be due to our longer overall life cycle, coupled with our shorter faces and delayed timing of mechanically safe spaces, which leads to the late age of our molars." ”

The posterior molars of primates are located directly in front of the two temporomandibular joints, which together form a hinge between the mandibular and skull. Unlike other joints in our body, these two pivots must be in perfect sync with each other. They also need to transfer some level of strength to one or more points to enable you to bite and chew.

In biomechanics, this three-point process is controlled by a principle known as the constrained horizontal pattern. Putting a tooth in the wrong position, the force generated in this mode can be bad news for a jaw that simply can't withstand.

For species with longer jaws, the time it takes the skull to form a suitable structure for the teeth closest to the muscles near the hinge is relatively short.

Humans with distinctly flatter faces have no such luck, and we need to wait until the skull develops to a certain extent so that the force exerted on each constituent molar does not damage our developing jaws.

Taken together, the study provides a new perspective on the condition of teeth, through which it can observe long-known connections between tooth development, skull growth, and maturation features; and it can also help paleontologists better understand the unique evolution of the jaws of human ancestors.

Thesis Link:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abj0335