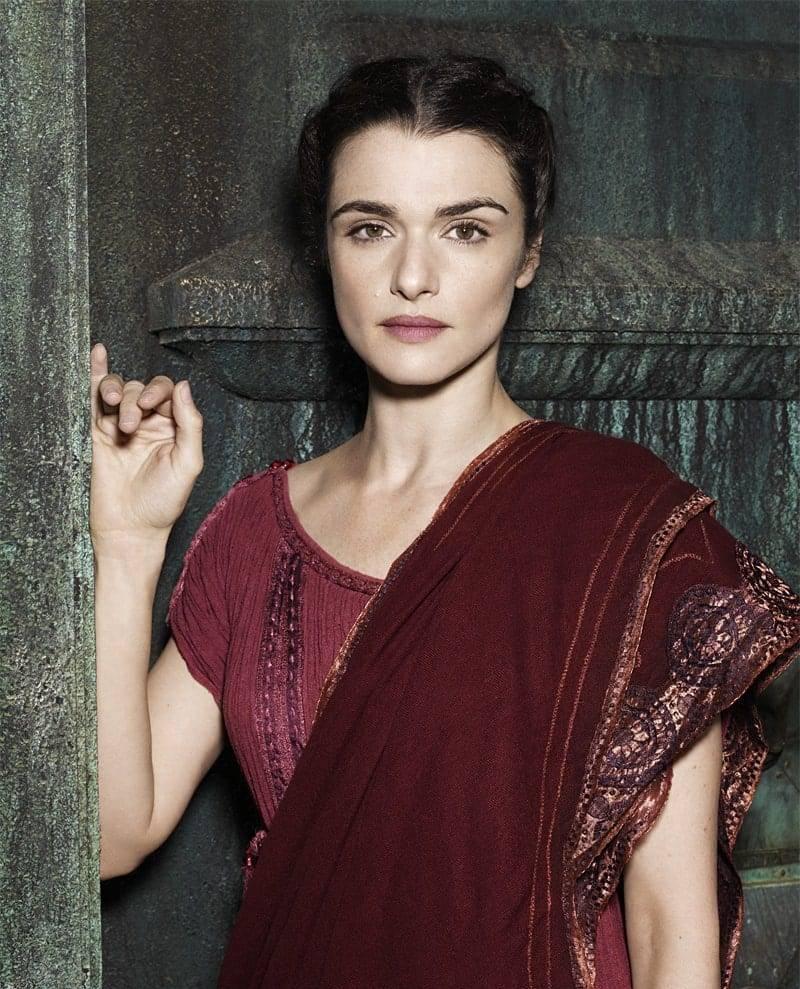

Rachel Weiss as Hypatia in the film

Hypatia, the first female mathematician, philosopher, and astronomer in Western history, was a legendary scholar even in ancient Rome and Greece.

But such a goddess of wisdom was tragically killed in the streets by the misfortune of being humiliated and dismembered, and died at the hands of a group of extremist Christians.

Her death pulled down the curtain of ancient Greek and Roman civilizations, and the long night of obscurity fell.

19th-century theatrical actor as Hypatia

Let's start with the tragedy of Hypatia:

It was an early morning in March 415 A.D., on the outskirts of the Eastern Roman Empire, in Alexandria, Egypt, and a beautiful woman, dressed in a white Greek robe as usual, sat gracefully in the carriage returning home, and she was Hypatia, and everything seemed the same as ever—fate always turned its face in a flash.

Charles William Mitchell, Hypatia, 1885, oil on canvas, 244.5cm*152.5cm, in the Tyne and Vail Museum.

A group of extremists, led by a priest named Peter, surrounded the carriage, pulled Hypatia down, beat her and dragged her into a church, stripped Hypatia of her clothes, cut off her flesh and blood little by little with a sharp oyster shell, cut off her eyeballs and limbs, brutally dismembered her body, and dragged her limbs all the way to a place in the suburbs called Sinalon and burned them.

Screenshots from Agora tell the story of Hypatia

Hypatia's death caused a sensation throughout the Roman Empire, and scholars were long considered worthy of respect, and countless nobles sent their descendants to study philosophy: only to end up with a female scholar being tortured and killed in the streets.

Why did Hypatia suffer from this? Is it a political struggle or a religious factor? Or tell a story while watching the painting.

Hypatia was born around 355 AD, and her father, Theon, was the curator of the Library of Alexandria and the author of the surviving texts of the famous Thirteen Books of Euclid Elements. Born in such an environment, Hypatia was carefully cultivated from an early age, and she herself was also very intelligent, and at the age of 19 she edited and annotated her father Theron's "Ptolemaic Synthesis of Astronomy".

As an adult, Hypatia remained in Alexandria to teach mathematics and other subjects, working with his father for many years, and together they revised Euclid's Primitive Geometry, which remained the standard version of the textbook for the next thousand years. Hypatia also completed his own annotations to the Cone Curve by the Greek mathematician Apollonius and the Arithmetic by the Greek mathematician Diophantus.

She then began to teach philosophy, as a moderator of the New Platonic Institute of Alexandria, writing books on Plato and Aristotle, as well as in mathematics and astronomy. Poets of the time called her "Holy Virgin" and "Flawless Star," and she often wore the robes of philosophers and preached in public. Her students came from all over the world, but most of them were the aristocratic elite of the Roman Empire, because according to the tradition of the time, they often had to receive education in philosophy, debate, and so on before entering politics.

In this way, Hypatia gradually became a well-known teacher at that time.

The historian Socrates, a contemporary of Hypatia, described her in the History of the Church this way:

Alexander had a woman named Hypatia, the daughter of the philosopher Theon, whose literary and scientific achievements far exceeded that of all the philosophers of her time. Inheriting the schools of Plato and Plotinus, she explained philosophical principles to her audience, many of whom came from afar to receive her guidance. Because of her mental cultivation, she behaved freely and calmly, and she did not feel shy about attending men's gatherings. Because all men admire her even more for her extraordinary dignity and virtues.

Astrolabe, 1885

She was an all-rounder, and in her invention, there was the original flat astrolabe, a density measuring instrument for water, and a liquid level measurement system.

Unfortunately, Hypatia lived between the classical and the Middle Ages: roman, Greek, and Christian ideas intertwined like a whirlpool. In 380 AD, the Roman Emperor Theodosius I proclaimed Christianity the state religion of Rome, and in 392 AD, Theodosius issued a series of anti-pagan decrees that removed pagan festivals from the calendar, prohibiting people from sacrificing in non-Christian temples and forbidding access to pagan temples.

It was during this period that our modern and influential Olympic Games were abolished by Theodosius.

This series of repressions, of course, provoked a backlash: unrest soon broke out between Christians and pagans in Alexandria, where Hypatia was located. In 391 AD, local Christians looted the Library of Alexandria, destroying centuries of collections and research, and about 5 million volumes.

And Hypatia's fame also made her a bird of prey: she did not believe in Christianity, did not obey the pope, and her Neoplatonism had a great influence on the local Christian elite.

This, of course, encroaches on the living space of the missionaries – how to interpret the world is a fundamental question that can be controlled by others?

More crucially, Hypatia was also embroiled in political struggles:

At that time, the egyptian provinces were led by the governor Orestes and bishop Cyril, and the governor and bishop did not interfere with each other, but at that time Christianity had just been established as the state religion, and the momentum was gaining momentum, so Cyril single-handedly covered the sky, and even the public affairs of the municipality had to be mixed, which of course caused the viceroy's dissatisfaction - and the governor was a good friend of Hypatia.

Hippatia drama, January 1893, based on Charles Kingsley's novel

Subsequently, bishop Cyril drove out Christian Novatia and Jews successively, fanatically eradicating paganism, destroying temples and monuments, a process that was of course bloody and cruel, and in the turbulent city of Alexandria, there were even missionaries who threw stones at the governor in the streets, and although they were executed by the governor, the bishop of Cyril declared the attackers martyrs.

Soon, more and more religious extremists targeted Hypatia, and they began to criticize Hypatia's school, portraying her as a witch and framing her for performing magic: such a beautiful, wise, and beloved Hypatia, but not believing in God, were those who worshipped her and praised her under the ruse and sorcery of Hypatia?

More crucially, Hypatia's public opposition to Pope Pauline's teaching that women should submit to men and remain silent in public also made her a thorn in Cyril's eye and a thorn in her flesh.

It can be seen that the death of Hypatia was not only a direct religious conflict, but also a power struggle between the emerging Christian forces and the old magnates of the empire, but also a struggle between classical culture and religious thought, scholars and missionaries who would explain the world.

The innocent Hypatia was thus destined.

Centuries later, medieval chroniclers are still repeating this lie, fabricating history for their own bloodshed:

In those days, Alexander saw the emergence of a female philosopher, a pagan named Hypatia, who had devoted herself to magic, astrolabes, and musical instruments, and she had seduced many through Satan's machinations. The lord of the city [Orestes] held her in high esteem; for she had deceived him with her magic.

Chronicle, LXXXIV.87-88, 100-103 (John Auf Nikai, 7th century CE)

Whether this rumor was initiated by Cyril himself is uncertain, but it was indeed Cyril's supporters who carried out the inhumane lynching— and later Cyril was also canonized in Christianity.

There are only two ways to convert or to die, to be stigmatized as a witch queen of Hypatia.

Soon, a group of radicals, led by a priest named Peter, intercepted Hypatia in the street, stripped her naked in the church, and killed her with a sharp oyster shell, her body torn apart by five horses, abandoned in the wilderness and burned. Onlookers even wrote down the words of the mob, who screamed loudly: "Paul told us that women should be silent, and now she has obeyed".

The first female scientist, mathematician, astronomer and philosopher in human history, the last teacher of platonic school, the founder of Plato's school of Alexandria, the wise life of Hypatia was thus ended by religious ignorance.

In the end, no one was punished for this, and the Holy See put an end to the incident. The atrocities led to the exodus of many scholars, and the ancient center of scholarship in the city of Alexandria declined.

▲ "City Square" film Hypatia stills (network map)

In modern times, Hypatia has become both an idol for many women and a symbol of anti-religious ignorance. In the 18th century, Enlightenment philosophers such as Voltaire enthusiastically praised her story, and even aroused the anger of the Roman Catholic Church, and the church's official rebuttal responded that "Hippatia in history is the most wanton mistress."

In the 19th century, the anti-Catholic Charles Kingsley wrote the best-selling novel Hypatia, which was later adapted into a play that swept across Europe. In the 1980s, modern scholars founded the journal Hypatia, which focused on the philosophy and women's issues studied by women scholars.

Hypatia's death can be said to have brought the entire "classical world" to an end, the light of reason was extinguished, the academic freedom of the ancient Greek and Roman periods ended, and the West began to step into the "dark Middle Ages". Even more than a thousand years later, scholars like Bruno suffered the misfortune of hypatia and died for upholding the truth.