Wang Hongchao

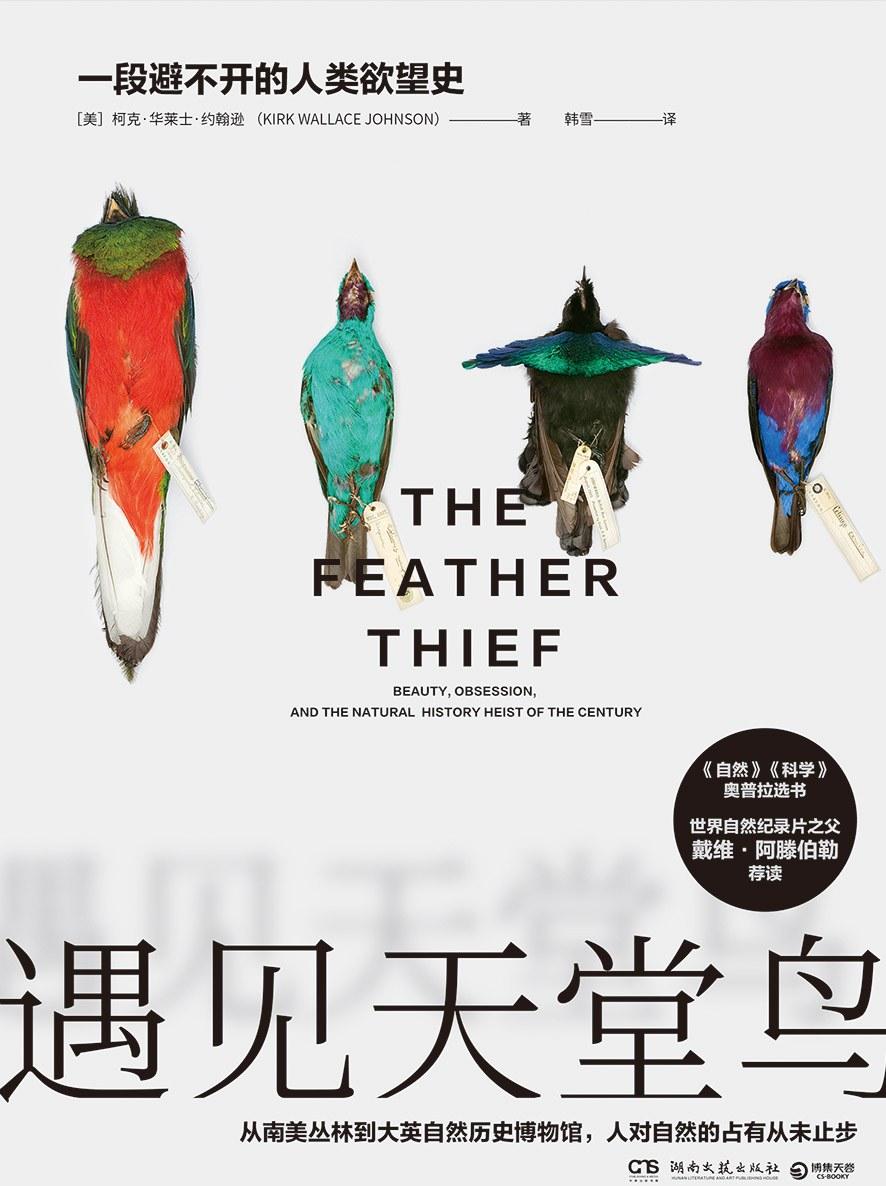

"Meeting the Bird of Paradise: An Unavoidable History of Human Desire", by Kirk Wallace Johnson, translated by Han Xue, Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House, August 2019 edition, 272 pages, 45.00 yuan

Theft at the British Museum of Nature

On the morning of July 28, 2009, Mark Adams, a senior researcher in charge of the bird collection at The Natural History Museum at Tring, went to work at the museum as usual. After work, he received visiting scholars to visit bird specimens. Part of the British Museum of Natural History, the Trin Museum is the world's largest collection of bird specimens, with 750,000 bird skin specimens, 15,000 bird skeletons, 170 million soaked specimens, 4,000 bird nests and 400,000 bird eggs.

When Mark Adams pulled out a drawer containing a specimen of the red-collared fruit umbrella bird, he found it empty. Nervously, he opened another drawer, still empty. He hurriedly opened several other drawers, and the scene in front of him terrified him—dozens of specimens of birds of paradise were gone.

The museum hastened to report the case to the hertfordshire police. An inventory revealed that a total of two hundred and ninety-nine bird skin specimens of sixteen different species had been missing. The theft brought police into contact with a report from the Trin Museum thirty-four days earlier. On the evening of June 24, museum security guards patrolled after watching the game when they found a window broken. The museum's staff were most worried about their town treasures: the bird specimens that Darwin had collected during his voyage with the Berger, and the bird specimens collected by John James Audubon and his book Birds of the Americas, "The Most Expensive Book in the World" (84 pp. The treasure of the town hall is still there, and the police investigation has not found anything suspicious, and they all agree that perhaps the fans on the side of the road finally smashed the window. The matter is closed.

750,000 bird specimens are stored in more than 1,500 cabinets, and it is difficult for the staff to conduct a comprehensive inventory. Could the July 28 theft have happened on June 24? Thirty-four days have passed, and the surveillance has not retained data for so long that it cannot be confirmed. Sheriff Adele Hopkin, who was in charge of the case, personally conducted an investigation of the scene and found a small piece of rubber glove and a small glass knife among the remaining broken glass. She decided the case took place on June 24. After checking with the museum staff, she came to a rather puzzling conclusion: the purpose of the thieves was not for scientific research, perhaps only to obtain the feathers of the colorful and exotic birds.

Wallace's adventure

Among the many collections of the Trin Museum is a special collection of bird specimens from the naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace. A naturalist with the same name as Darwin, he is also a giant of the forgotten history of science and intellectual history. (For Wallace's life, see Peter Rebbe, translated by Lai Luming: The Collector of Nature: Wallace's Journey of Discovery, The Commercial Press, 2021.) )

Peter Rebbe, translated by Lai Luming: The Collector of Nature: Wallace's Journey of Discovery, The Commercial Press, 2021.

In his twenties, Wallace saw fellow Darwin's Voyage of the Beagle, which sparked a passion for exploring and collecting species. He chose the most challenging place, the Amazon Basin. Wallace harvested a lot there, and when he had to return home early four years later due to yellow fever, he already had more than 10,000 bird skins, many specimens of bird eggs, plants, fish and beetles, and a batch of expedition notes. "These specimens are enough to make him a top naturalist and add to his life's work." (p. 7) But on the way, the ship caught fire, and Wallace watched as the specimens collected at the risk of his life were buried in the fire. He lost everything.

But Wallace did not get depressed in the predicament, and after recovering, he reloaded on the road. Against the backdrop of many naturalists scrambling to find new species, it would be pointless to return to the Amazon, and he would need to find new gaps to re-establish himself. With the foundation of his research, coupled with his talented insight, he really found that blank spot— the Malay Archipelago. This time he changed his previous practice, no longer putting all the specimens together and bringing them back to The End, but sending them back to Europe in batches in time. Most of these specimens were purchased by the British Museum of Natural History. During World War II, in order to escape german bombing, the museum transferred specimens collected by Wallace and Darwin to the Trin Museum, which became the most important collection.

[English] Alfred M. By R. Wallace, translated by Kim Heng-bis and Wang Yizhen: A Natural Expedition to the Malay Archipelago, People's Literature Publishing House, 2018.

In his investigation and research, Wallace has been thinking about what exactly causes species differences and changes.

I suddenly thought of the question, why do some species die and some survive? The answer is obvious – overall the most suitable survived. The healthiest escaped disease, the strongest, the most agile, the most cunning dodged the enemy, and the best predators survived famine. (19 pages)

Yes, he is proposing "survival of the fittest." Wallace could not suppress the joy in his heart and wrote to his idol Darwin about this idea. Wallace's letter left Darwin deeply worried and confused, because Wallace's idea was the same idea he had been thinking about for years and had not yet published. And, surprisingly coincidentally, they all use the same terminology. Darwin wrote worriedly to his friend:

I hadn't originally intended to publish any theoretical outlines, but could I (simply) hurry up and publish them because Wallace had sent me a copy of his outline? I'd rather burn my entire book than see him or anyone else seeing me doing it as the work of a kinsman. ([Dan] Hanne Strager, translated by Daigang: A Biography of Darwin, CITIC Press, 2020, p. 166)

But at the subsequent Linnaeus Society, the views of the two men were faithfully published. The importance of theory made everyone put aside the concerns of the dispute over the right to invent, and also won the glory of history for darwin and Wallace.

Eight years later, Wallace was already famous when he returned from an expedition to the Malay Islands.

Bird of Paradise: An object of beauty and desire

Wallace set out on his expedition to the Malay Archipelago with a special dream, which was to find the bird of paradise.

Before the nineteenth century, the bird of paradise was a mysterious existence in mythology for ordinary Europeans. In 1522, the Spanish navigator Juan Sebastian Elcano bought five bird skins from the natives of Moluca in Southeast Asia and returned home to offer them to the King of Spain. This was the first time Europeans had seen a bird of paradise. Because of the indigenous way of making bird skin specimens, these birds have no feet, so Carolus Linnaeus, the father of taxonomy, named it "Paradisaea apoda". Many Europeans also believe that this bird dwells in heaven, is born to the sun, feeds on jade liquid jelly, and does not fall into the earth until the moment of death. They believe that the female lays eggs on the backs of their mates and hatches them. (pp. 11-12)

John Gould's Red-feathered Bird of Paradise (Bird of Paradise), originally from Gould's The Birds of New Guinea and Adjacent Papuan Islands, from Mark Ketzby, John Gould et al., translated by Tong Xiaohua et al., Discovering the Most Beautiful Bird, The Commercial Press, 2016.

Goldfinch bird of paradise painted by John Gould, ibid.

Most of the birds of paradise on Earth are on the island of New Guinea, where a unique natural environment and groups of species have formed due to the drift of the continental plate. Although Wallace had already understood and studied the bird of paradise before the expedition, it was very shocking to see the real bird of paradise:

In terms of the configuration and texture of the feathers on this little bird alone, it is already comparable to the best of jewelry, but its wonderful beauty is far more than that... The pectoral feather fan and the tail feather at the end of the spiral are unique products, unique among the 8,000 species of birds in the world, and with the most elegant plumage, this bird is one of the most adorable species in nature. ([English] Alfred M. By R. Wallace, translated by Kim Heng-ho and Wang Yi-jin: A Natural Expedition to the Malay Archipelago, People's Literature Publishing House, 2018, p. 198. )

Little emerald bird of paradise painted by Levayan. Le Wayan wrote The Natural History of the Bird of Paradise (1806), the most informative work on the bird of paradise at the time. Image from [French] François Levalyan, [English] John Gould, [English] Alfred Wallace, translated by Tong Xiaohua and Lian Guanyi: "In Search of the Bird of Paradise", Peking University Press, 2017.

The bird of paradise, because of its beauty and rarity, has naturally become the object of human desire. In the late nineteenth century, the feather fever was popular in Europe, and women used bird feathers as a fashion decoration to highlight their identity and status. The bird of paradise is naturally the focus of the pursuit of wealthy women:

Due to the constantly changing laws of fashion, each occasion requires a specific hat, and each hat requires different kinds of birds to decorate. Women in the United States and Europe scrambled to buy the latest feathers, and they put their entire bird skins on their hats, so flashy and so large that they had to kneel or stick their heads out of the window when they rode in the carriage. (31 pages)

A lady who decorates a hat with a whole sheet of bird of paradise skin, around 1900. Image from Meet the Bird of Paradise: An Unavoidable History of Human Desire.

In fact, China also has a tradition of feather decoration, and later it is also popular to buy feathers from outside the region. Some scholars speculate that the bird of paradise has long entered China, and the feathers of the bird of paradise may be in the flower plumes of Qing Dynasty officials. (Hu Wenhui, "The Problem of "Jade" and "Cui Yu" and "Cui Mao": Birds of Paradise Entering Chinese Speculations," Chinese Culture, No. 41, 2015)

Europe's feather fever intensified in the last decades of the nineteenth century, with France importing nearly 100 million pounds of feathers and London auction houses auctioning 155,000 birds of paradise in four years, and that's just the public auction figure, perhaps just the tip of the iceberg. Feathers were used as fly bindings after hats were not used to decorate hats, which was also a huge market, and there was no shortage of people who became rich as a result, such as Paul Schmookler. At the time, Sports Illustrated said:

If Donald Trump can't afford to pay the taj mahal casino, he might be able to give a phone call to paul Schmerkler, a former classmate at the New York Military Academy, for tips on how to make money. (48 pages)

Donald Trump did find the trick to making money, but not because of fly binding.

The lust for feathers has led to the extinction of some bird species, and birds of paradise face this fate. Wallace foresaw this result when he was in the Malay Islands:

In the unlikely event that a civilized man arrives on these remote islands and brings moral, academic, and physical knowledge into this deep virgin forest, we can almost certainly destroy the otherwise good balance between nature and inorganic, and that even if only he could appreciate the perfect structure and beauty of this creature, it would lead to its extinction and extinction. ([English] Alfred M. By R. Wallace, translated by Kim Heng-ho and Wang Yi-jin: A Natural Expedition to the Malay Archipelago, People's Literature Publishing House, 2018, p. 199. )

Later, the subsequent anti-feather trade movement in the West somewhat curbed the trend of the extinction of the bird of paradise. It is not that human desires are satisfied or conscience is discovered, but that as fashion shifts, human desires are temporarily filled by other objects.

Edwin the Thief: Genius and Morbid Fun

The theft of the Trin Museum, after more than a year of investigation, has made no progress. In late May 2010, an Irishman who had attended the Dutch Fly Show called Hertfordshire Police and said that there was a suspicious person on e-Bay with the username "Flute Player 1988" and that he had multiple rare bird skins for sale. Sheriff Adele hurried to investigate and learned that the man's real name was Edwin Lister. He did sell bird skins and appeared on the Trin Museum's visitor list for November 5, 2008.

Edwin is a student at the Royal College of Music in London and is from the United States. At this time, he was still on vacation in the United States, and the police had to wait for him to return to school in the fall. During this time, police also investigated Edwin's online shopping records, including a glass knife.

On the morning of November 12, 2010, Sheriff Adele and her colleagues arrived at Edwin's residence while he was still asleep. Edwin immediately pleaded guilty when he saw the search warrant, and the interrogation went quite smoothly, and he also handed over the unsold bird skins. Five hundred and seventy days have passed since the theft.

Edwin stole specimens of bird skins from the museum, really just to get those pretty feathers.

Edwin had been practicing the flute since he was a child, but once became fascinated after seeing a video footage of a trout fly. Flying flies, simply put, are fish hooks decorated with feathers. Different fish, different environments, different times, the use of fly will also have subtle differences, this refinement of the pursuit makes fly binding a unique skill. Flying flies are especially used when fishing for salmon. Salmon have a special habit of not eating after spawning, guarding the spawning area, and if attacked, they will bite it. So salmon flies are not meant to hide their hooks, "but to provoke provocation" (p. 42). A beautiful fly dotted with various feathers can really anger these "fish kings". Anglers have raised the technique of fly flying to the level of pure fire, which in turn has become an art.

Spencer Sam's bound fly. Image from Meet the Bird of Paradise: An Unavoidable History of Human Desire.

Ever since he became obsessed with fly binding, Edwin began experimenting on his own, until he met George Hooper, an evolutionary biologist and fly binding enthusiast. Under Hooper's guidance, Edwin's skills improved, and Hooper encouraged him to participate in fly binding competitions. Edwin stood out in the competition and won the first place.

While Edwin was overflowing with triumphal joy, he suddenly "saw something shimmering in the midst of a dazzling multitude of exhibits, which distorted his hobby and turned it into an obsession" (p. 54). What he saw were some Victorian flies. The Victorian fly is the ultimate in luxury and is the object of admiration in the minds of all later enthusiasts.

Edwin tied up flies. Image from Meet the Bird of Paradise: An Unavoidable History of Human Desire.

Edwin has become more and more famous in the circle under the guidance of many famous teachers, and he is seen as the future of the fly binding world. After Edwin mastered all his skills, he realized that what was really holding him back from reaching new heights was his lack of those truly perfect feathers. The best feathers are undoubtedly the feathers of the bird of paradise.

In 2007, Edwin was admitted to the Royal Academy of Music, and his dream was to become the concerto flute player of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, which is his real-life identity. Fly binding is like the dream of his other self, a utopia he has constructed. He spends almost all of his spare time tying flies, and he uses all opportunities and resources to obtain feathers. But these were far from fulfilling his most perfect ideals. Those feathers were too expensive for a poor student.

Until one day, Edwin received an email from Luc Qutiglier telling him to go to the Trin Museum. This look put Edwin on a path out of control.

The protagonist of the theft, Edwin Lister

After Edwin's arrest, the facts investigated by the police were clear and the evidence was conclusive, and he had to wait for a trial. The only thing you can do at this time is to hire a good lawyer as much as possible. Peter Dahlsen, who was sure to be a good lawyer, suggested a psychological assessment of Edwin and contacted Simon Baron-Cohen, a cambridge professor. Barron Cohen is Director of the Cambridge Autism Research Centre and an international leading scholar on autism research. He provided a psychological diagnosis to Gary Mckinnon, a hacker who invaded the Pentagon, which led Britain to refuse an extradition request from the United States, based on Asperger's syndrome.

During the conversation, Edwin "explained to Barron Cohen the uniqueness of each feather", and Barron Cohen was extremely impressed by Edwin's immersion, concentration, and pursuit of perfection, believing that Edwin did not steal out of greed, but developed an irrepressible obsessive-compulsive interest in fly binding. He takes fly binding to new artistic heights, and due to "excessive attention to this art form (and all its intricate details) to the point of forming a typical 'tubular vision', he can only think of materials and works that aspire to be bound, without considering the social consequences that he or others need to bear". (p. 121) The psychopathologist believes that Edwin's behavior is perfectly consistent with the symptoms of Asperger's syndrome.

Crime for art, what an elegant statement. The defense of the criminal always provokes the anger and resentment of the masses, but the defense of the genius wins sympathy and tolerance. If it's not a genius, shape him into a genius. Besides, Edwin really had the shadow of genius.

On 8 April 2011, the case was heard in criminal court. After court arguments, the judge finally sentenced him to twelve months' imprisonment with a suspended sentence. Edwin doesn't need to spend a night in jail. This was presumably an outcome that surprised Edwin himself, who could have spent thirty years in prison. On June 30, Edwin also successfully graduated from the Royal Conservatory of Music with a diploma.

Johnson: The interloper of the story

Except for Edwin and his family, probably no one will be satisfied with the verdict. These specimens, which embody the lifelong efforts of many naturalists, have irreplaceable significance for the study of species and natural ecology, and the damage caused by destroyed feathers is huge and irreparable. The verdict is already in effect, and apart from the fact that museum staff will have to spend a lot of time repairing surveillance equipment and sorting out the recovered specimens, others may soon forget about the case. Who cares if such a case does not involve the interests of an individual?

At this point, an interloper with nothing to do with the matter emerged, Kirk Wallace Johnson, the author of the book "Meet the Bird of Paradise." Johnson worked at the United States Agency for International Development, where he coordinated reconstruction efforts in the Iraqi city of Fallujah. In the midst of the tumultuous and painful work, he approached the brink of depression. For a while he used fishing to save his life. During a fishing trip, his fly fishing instructor Spencer Seim mentioned the Edwin theft in small talk. Just hearing a musician enter the British Museum of Nature to steal feathers will intriguate everyone.

Kirk Wallace Johnson

Johnson, in a state of frustration at work, became extremely interested in this bizarre and bizarre event. He first calculated a simple mathematical problem: the museum had stolen two hundred and ninety-nine bird skins, and recovered one hundred and two labeled ones and seventy-two without labels from Edwin's dormitory. After the police filed the case, the buyers sent back nineteen copies one after another. But one hundred and six bird skins are still missing. Where are those bird skins?

"This crime is so bizarre that it keeps me distracted." (p. 137) Unquenchable curiosity prompted Johnson to consult information about the case. He had no purpose, just curiosity, or simply to transfer the pressure of his work.

Johnson approached the fly-bound colony, and the first explanation he found was that the Trin Museum probably hadn't lost as many two hundred and ninety-nine sheets at all. The museum's collection is too large, and it has not been counted for at least a decade. Perhaps the two hundred and ninety-nine lost were stolen over the course of ten years:

Did I imagine a mystery that didn't exist? Was someone else taking the bird skins before Edwin? Could it just be that museums get the number wrong — they have hundreds of thousands of specimens in their collection and may not know the exact number? Could it be that on the day Edwin was arrested, all the bird skins had already been recovered in his apartment? Will there be no more birds missing? (142 pages)

These claims all seem reasonable, but they all seem to be full of doubts. The key is the evidence.

Johnson first went to the Trin Museum, and after communicating with the researchers, he basically believed in the authenticity of the data. Moreover, the museum has done it more carefully. They restored the recovered feathers, calculated "the approximate number of specimens represented by feathers and bird fragments," and concluded more precisely: sixty-four bird skins were missing.

Johnson's new question is, was Edwin a man who committed the crime? According to Edwin, he had come to steal with a suitcase, smashed glass, entered the museum, put bird skins in a suitcase, and left by train. But can two hundred and ninety-nine bird skins fit into a single box? After Edwin pleaded guilty and closed the case, the police naturally stopped the investigation. But could it be that Edwin had protected his accomplices with a confession of guilt, and the sixty-four bird skins were still in the hands of his accomplices? Or maybe the birds were still in Edwin's hands, and he hid them, and when the limelight passed, he would take them out. That's a lot of money.

But as the investigation deepens, the difficulty becomes greater and greater. After Edwin's arrest, his website ClassicFlyTying.com, which betrayed bird skins, removed everything related to it. Such cases would offend the interests and ecology of this group, after all, buying and selling bird skin specimens is often a trade on the boundary between legal and illegal. Just when Johnson was at a loss, he discovered a "time-travel machine" software that retained web traces through web snapshots crawled by web spiders. Johnson suddenly had all the information on the Edwin deal.

Johnson, after carefully browsing Edwin's trading profile, finally made a surprising discovery. Many of Edwin's deals were posted through another user: Goku. This person seems to be an agent of Edwin's online trading. But the trouble is that since the Edwin incident, this user has not appeared on the Internet. Johnson later learned from Yale University professor Richard M. Johnson, who was equally concerned about the progress of the matter. In the information provided by Richard O. Prum, it was gradually revealed that "Goku's" name was Long Nguyen. Will he be behind it?

Some people on the Internet are talking about "his partner is still at large", targeting Ruan Long. Edwin then issued a statement saying that although Nguyen Long had helped him, Nguyen Long had nothing to do with the theft and was responsible for it. To further confirm this, Johnson tried to contact Edwin directly to meet with him in the hope of getting some information from him. Johnson also knew that this was futile, how could a person who had been tried in court possibly provide new evidence against him? Moreover, the meeting is also full of dangers, just like the scenes often seen in Hollywood movies, when the respondent is desperate, he will give the person who is staring at him a little color. Johnson, of course, knew this, and before he met Edwin, he hired a large bodyguard to hide outside the door, and if there was any movement, the bodyguard would knock on the door at any time.

Not surprisingly, Johnson did not get any new information during his conversation with Edwin, but Johnson realized that Edwin did not fit as Asperger's syndrome. People with this condition have social impairments, and Edwin is a smart, sensitive, and alert interlocutor.

Johnson also wanted to meet Nguyen Long. Nguyen Long is also a genius in fly binding, he is a Norwegian of Vietnamese descent who met Edwin because of a common hobby. Edwin was a master figure in Nguyen Long's eyes, and they quickly became good friends after meeting. Nguyen Long began helping Edwin sell bird skins and feathers online. Johnson realized that Nguyen Long was a mere admirer, and Edwin took advantage of that sense of worship. All the trades were dominated by Edwin, and Nguyen Long didn't know where the remaining bird skins were. But in the end, the guilt-ridden Nguyen Long also admitted that Edwin had sent him about twenty bird skins and eight hundred Indian crow feathers.

Johnson did not stop the pace of the investigation, and he targeted a man named Luc Qutierje. This man was Edwin's mentor in tying, known as the "Michelangelo of the fly-binding world", and it was from him that Edwin first heard about the Trin Museum. On the Internet, you can find records of bird skin transactions related to Quttiriya, probably more than twenty. But after Edwin's accident, Coutirier evaporated.

As Johnson approached Coutirier step by step, he saw Coutirier's obituary.

Incurable nostalgia

Although the number of unaccounted bird skins had been reduced to twenty, Johnson could no longer find any clues to trace. He exhausted all the details and approached the truth, but the truth could not be truly restored.

At this point, Johnson realized that he was not facing Edwin alone, but the entire fly-trap community:

There are avid fly-tyingrs, feather dealers, addicts, beast hunters, former detectives and invisible dentists. It was full of lies and threats, rumors and false news, truths and setbacks, and I began to understand the evil relationship between man and nature, and the endless desire of human beings to possess the beauty of nature at all costs. (10 pages)

Victorian luxury pushed feather ornamentation and fly binding to the extreme, and a new generation of binders took this as a perfect example, not only pursuing form, but also material. The bird of paradise still did not escape the doom. If this is a nostalgic feeling, it is also an incurable nostalgia, as Svetlana Boym put it in The Future of Nostalgia: "In the seventeenth century, nostalgia was considered a healing disease, similar to the common cold... In the twenty-first century, the disorders of the past that should have been left behind have become incurable modern diseases. (Svetlana Boym, translated by Yang Deyou, Nanjing: Yilin Publishing House, 2010, p. 2) If literary and artistic nostalgia has aesthetic value, this destructive nostalgia is just a shoddy and blind imitation.

It cannot be said that Edwin is a thief and a liar outright, but he steals beauty for desire, after all, it is still a crime. Edwin's pursuit of fly binding technology is exactly like creating a work of art, and fly binding has long been separated from practical functions and become a purely artistic form for these high-level enthusiasts. But Edwin, they cannot be counted as artists, not because of their skill, but because of their attitude towards feathers. As Kant said, "We must not have the slightest tendency toward the reality of things, but have a completely indifferent attitude in this regard, in order to act as judges in matters of appreciation." "Aesthetics are pure. Edwin had only desire in his eyes.

Human desire for things is always there, but sometimes this desire is cloaked in aesthetics. "Closing beautiful things tightly so that one can enjoy them alone" ([Fa] Jean Baudrillard, translated by Lin Zhiming: The System of Things (Revised Translation), Shanghai People's Publishing House, 2018, p. 108), is a situation that often occurs in the relationship between people and objects. Beauty, which is closed tightly, becomes a slave to desire, no longer an object of beauty. The story of the bird of paradise also allows humanity to reflect on the relationship between man and living things, with nature, with all objects, and with human desires.

The story of the bird of paradise is far from over...

Editor-in-Charge: Huang Xiaofeng

Proofreader: Luan Meng