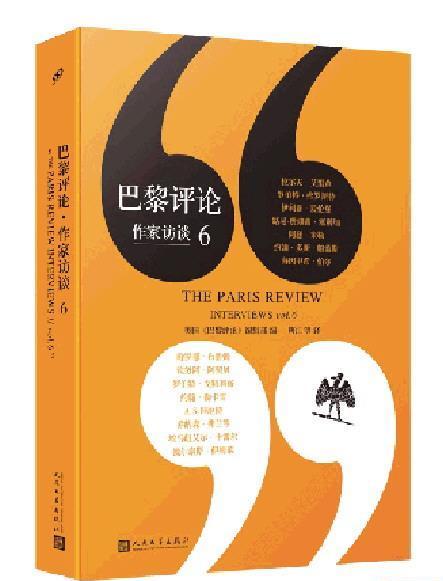

"Paris Review writer interview 6", edited by the editorial department of the Paris Review, People's Literature Publishing House, March 2022 edition, 65.00 yuan.

□ Jonathan

The Paris Review Writers Interview series is a book that literature lovers love to read, and indeed deserve to be seriously read. In 2012, when the first of the series was published in China, I wrote a short essay titled "On the Quality of translation of the Paris Review writer's Interview I", which was published in the Southern Metropolis Daily. In the blink of an eye, ten years later, the series has come out to the sixth. Recently, I read the Paris Review Writers Interview 6 against the original article and found that the quality of the translation was about the same as it was ten years ago. There are 16 interviews in the book, and I have selected 9 places with deviations in the understanding of the meaning of words from the translations of the previous two interviews, and explained them slightly for the reader's reference. As for other mistranslations, this time it is not listed.

The first was interviewed by Ralph Allison, an african-American writer and author of The Invisible Man. The opening paragraph mentions that "The Invisible Man" won the prize, and "the author points out with both frustration and satisfaction in his acceptance speech..." (p. 1) It is usually said that the award is a happy event, and people are not likely to be "depressed". The word corresponding to "frustrated" in the original text is dismay, which means "depressed" at all, and it generally means panic or discouragement. In fact, in the context of the writer's award, there is a word in Chinese that corresponds to dismay quite accurately, that is, "trepidation". Trepidation, both expressing panic and implying shame, is very appropriate as a humble remark.

Irison is unhappy with the critic's work, stating, "I don't want to sound like I apologized for my failures" (p. 10) The translator misunderstood the meaning of apology, and here it is not "apology" but "defense". Unfortunately, in some medium-sized English-Chinese dictionaries, the apology entry does not have a "defense" meaning, such as the highly acclaimed Oxford High-Level English-Chinese Dictionary. But as long as we look at the slightly larger dictionary, it is not difficult to find. For example, in the English-Chinese Dictionary edited by Lu Gusun, the second meaning of apology is "defense and justification". Chinese may be a little difficult to understand: apology and defense, how do the meanings of the two feel a little opposite? Apologizing for one thing is very different from defending one thing. In fact, the English-Chinese Dictionary gives a etymological explanation, the English apology comes from Greek and Latin apologia, and the meaning of "defense" is much earlier than the meaning of "apology". Let's look at Wu Fei's translation of Plato's Apology of Socrates (Huaxia Publishing House Edition), with Apologia Scoratis printed on the cover. The 16th-century English poet Philip Sidney wrote a book in defence of poetry, entitled An Apologie for Poetrie. Perhaps because I usually read english literature in written language, I am under the impression that the word apology appears as a "defense" no less frequently than as an "apology". The writer Allison's language is very written, and what he actually wants to express is: I don't want this to sound like I'm defending my incompetence.

The second interview was with the great poet Robert Frost. There are many mistakes in this article, and only the meaning of words is discussed here. The opening statement goes to England that after Frost's early departure to England, "he has turned down countless opportunities like the Georgians to lose himself in the currents and movements" (p. 18). The so-called "Georgian" here is inaccurately translated, the original text is the Georgians, referring to a group of British poets in the early 20th century, including Walter Delamer, Rupert Brooke, and so on. The name of the school of poetry comes from the accession of King George V to the throne in 1910, and their collection of works was later called Georgian Poetry. So perhaps the more appropriate translation would be "George V"—in any case, the word "Ya" should not appear.

Frost said of his mother: "She was a hard worker—very supportive of us" (p. 26) (she was a very hard-worked person—she supported us. The support here cannot be translated as "support", but as "offering", which means that she works tirelessly to provide for us.

In an interview, Frost mentions a poem by the 16th-century English poet Richard Edwards: "It was a difficult poem with the old saying: 'When a faithful friend departs, it is the day when love is born again.'" (p. 28) The falling out of faithful friends is the renewing of love. In fact, here the poet Edwards borrowed a famous saying of the ancient Roman playwright Terentius: "The quarrel between lovers is the renewal of love." (Amantium irae amoris integratio est.) If a translator looks up the English-Chinese Dictionary, the third meaning of the phrase fall out is "quarrel; discord." So, here is not "leaving", but "quarreling".

Frost recited his own poem: "I read the last few sentences: 'It's better to die decently/Have bought friendship around/It's better to have than nothing.'" Contribute, contribute! (p. 34) The so-called "contribute, contribute!" ", the original text is: Provide, Provide! The provide here translates to "contribute", which is really inexplicable, it actually means "prepare early". What the poet wants to say is: "Prepare early, prepare early!" ”

The poet tells an anecdote: "Once I was asked to go, in front of four or five hundred ladies, to talk about how to have leisure to write. I said, 'Secrecy — because there are only five hundred people here, and it's all women — I'm a little bit like a thief, a little bit like a man scratching a little bit — and now I have a little bit in my cup.' (p. 39) Three of these two sentences are not translated very accurately. The original text at the beginning is: I was once asked in public... The ask here does not mean "invite", but the most basic meaning of "ask". It begins by saying: I was asked in public... Looking at "confidentiality", the original text is Confidentially, which translates as "confidentiality" is too rigid. Here, its meaning is equivalent to the "speak your own words" that are used in novels such as "Dream of the Red Chamber", or we will say "I only tell you, you don't tell others". The "cup" in the translation, the original text is tin cup, this is not an ordinary cup, it has a cultural connotation, the translator is so simplified, the reader will not experience that layer of connotation. The so-called tin cup, which generally refers to the tin cup used by beggars to receive the change given by the giver, is somewhat similar to the so-called "begging bowl called Hanako" in Chinese. That's why Frost would then say, "Sounds like a beggar, but I never meant to be a beggar." "The great poet lowered his posture in front of the ladies, saying that he stole a little here, snatched a little there, or begged for a little. But Chinese readers reading the above translation are afraid that they will not be able to understand his meaning.

I've always believed that the premise of doing translation is to understand exactly what each word in the original text really means. If you don't even grasp the meaning of the word correctly, it is impossible to translate it well.