▲ Click on the video to watch more of the new book introduction of "Aunt Lily's Tiny South"

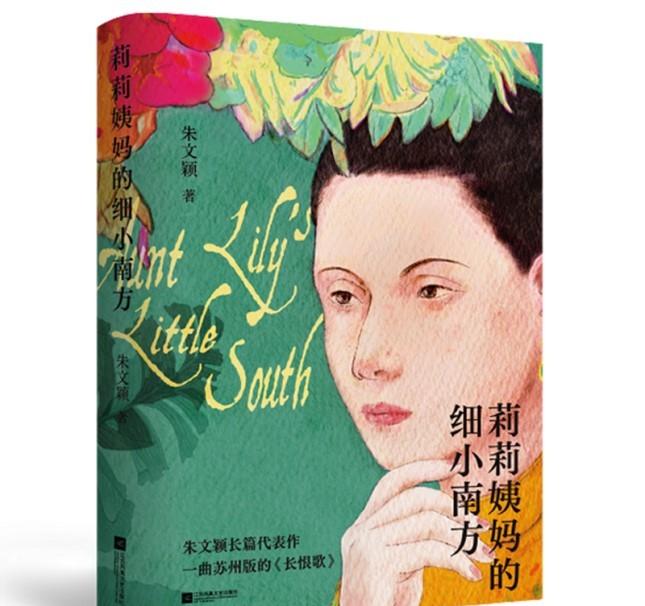

"Aunt Lily's Tiny South"

By Zhu Wenying

Published by Jiangsu Phoenix Literature and Art Publishing House

Zhu Wenying's novels belong to a category that is extremely difficult to grasp. Usually, there is a category of good novelists who are transparent and holistic, and the elements of structure and drama are like fish bones; the other is like Zhu Wenying, who is difficult to say about her kind of good, jumping out, broken, like the broken gold of the sunset shining on the surface of the water. Like most female writers, the psychology of her novels is always greater than the story, and the subjective narrative is always more than the objective description; at the same time, she is more "thin" than the average female writer, like the garden in Suzhou, small and multi-organ, with elusive twists and turns.

Sadness

Regarding the sentimentality of life, the impermanence of the world, and the rotation of fate, our ancestors have long had countless exquisite descriptions, and those touching poems have long become the psychedelic drugs that affect and shape a Chinese soul. And such a tradition, an aesthetic, is geographically and exceptionally typically gathered in the "south of literature" - the smoke and rain of Jiangnan China. Therefore, Zhu Wenying's reproduction of the "South" image, her persistent pursuit of her mirror image and Charm, in my opinion, is not an occasional random touch, but a cultural pursuit that comes from inner consciousness, a reconstruction of local traditions, family history and personal life memory, and a dream journey about the cultural spirit and blood inheritance of "Southern Imagination".

So let's talk about the character of "Aunt Lily". There is the intimate world, there is the elusive heart, there are small struggles and hidden pleasures, there are ancient and repetitive fates, this is a beautiful but vulgar woman to the bone. Zhu Wenying uses her to carry her own thinking and reliance on contemporary history, the contemporary evolution and fate of Suzhou or the "cultural form" of "south", giving her "small" a unique aesthetic significance. The grand history is destined to be inherently misaligned with her petite destiny and the natural "little South". At first she fell in love with Pan Jumin, who came from a capitalist background, and later had to marry Wu Guangrong, who came from the north and had a revolutionary resume, and they spent most of their lives in the division and union, after three divorces and two remarriage tragedies, and by the time she was more than 60 years old, aunt Lily was still fantasizing about the love with Chang Defa, who had been living in widowhood, with the dream of trying to open her double eyelids, maintaining her brilliance and posture with fashionable clothing. In a soft sunset, she complained about the impermanence and change of the world, and at the same time was full of excessive obsession and fanaticism about life.

Obviously, Zhu Wenying gave this elderly Suzhou woman a real and absurd meaning: a lifetime of yin and yang mistakes and fate bumps did not make her full realization, but still indulged in the daily life that had never favored her, which is absurd and sad both philosophically and historically; but perhaps this is the "south" that Zhu Wenying wants to write, and its soft and practical tenacity and "smallness". Tragedy and comedy are forever perpetually intertwined, entangled. However, as the mirror image and continuation of her life, "I", when she should really have life, fell into a almost hopeless depression and was completely tired of life. History and reality are here in the twist of the fracture, the decline in the continuation. If Aunt Lily carries more "the joy of history itself", then "I" undoubtedly hints at "the sadness and decadence of the historical examiners". This is another source of tragic style in the novel.

Long

It was a long life connected by fragments: the golden images, memories, scenes, and flashbacks of dream-like time gave me a glimpse of a small, private contemporary history. This is a main theme that Zhu Wenying hopes to construct in this novel, and it is also the structure of the novel itself. This is where the "sense of history" is born. If "sadness" constitutes the aesthetic style of "Aunt Lily", then "long" unfolds its historical space and proposition. Undoubtedly, this novel implies Zhu Wenying's ambition to write history. This corrects our usual perception that Southern writers were less enthusiastic and adept at portraying history. Here, Zhu Wenying strongly expresses her creative impulse to try to create a special historical form of "southern memory", and this ambition has indeed been realized. In a sense, if the work of "Long Hate Song" constructs "Shanghai in modern history", then "Aunt Lily" constructs "Suzhou in contemporary history".

The "strategy" of the historical narrative in "Aunt Lily" is noteworthy, and it adopts a staggered way of encountering face-to-face between "private scenes" and "grand history" and quickly avoiding them, which is the attitude of the characters and the attitude of the novel's narrative. History is even longer because of fragmentation and "microscopy", and the trance of personal memory of old dreams makes it "four or two pounds" to fictionalize the twists and turns of contemporary history, as well as its dramatic ups and downs.

The long feeling is also achieved through "repetition": the mirror image of "me" and Aunt Lily in the novel increases the length of history in the novel—"I will suddenly be curious about my intimate relationship with Aunt Lily." That natural sense of closeness, a smile on the face, the vanity of those trivial women... Sometimes I even feel as if there's a conspiracy in there. As a sample of "Suzhou women", Aunt Lily's history continues to extend in "me", no matter how different their encounters look, the things in their bones are still the same. The historical logic revealed by this family lineage is the soft vitality of that "southern" culture, its secular and powerful existence and will to continue.

Small

If "long" shows the length of southern history, then this "small" is undoubtedly the "spatial attribute" unique to southern culture.

The geography of the south, Suzhou - Shanghai - Hangzhou, this is about the spatial diameter of Zhu Wenying's novel, which is of course not "small", but from the meaning and attributes of culture, they are enough "small", this small is fine and exquisite, is feminine and soft, is careful, is to be soft and rigid... It exists in the human heart, in the abundance and even decaying daily life of the South. This is one of the foundations of Chinese culture, since the Six Dynasties, our ancestors have depicted its beautiful and decadent demeanor countless times, Zhu Wenying has only once again given it a concrete and vivid and vivid form, showing the maximum tension within the history of modern China implied here - no matter how history changes, the abstract and concrete, soft and powerful, loose and tenacious, bent and thus still my cultural body will always exist, unharmed. If we want to maximize the cultural significance of the novel "Aunt Lily", I think it should be a marker and boundary.

"The Small of the South" has countless ways, and the vividness of the novel is also reflected in this aspect, although its flashing and broken story lines are exhausting, but the narrative that always comes out of the branches is also joyful, the scenes of the night sailing boats on the canal, the bookstores that can be encountered everywhere on the banks of the canal, the leisurely time in the countryside hometown in the suburbs... Always play this "small" to the fullest.

There should also be a number of topics about Zhu Wenying's novels, such as imagery, thinness, and fragmentation, such as the innerization of the narrative, as well as talent, language, and even the charm of the tone and rhythm of the narrative, and so on. There are many praiseworthy, and there are naturally many who can be picky, such as the fullness of the story, the clarity of the characters' faces, and the drama of the story itself and the prominence of the sense of form, etc., which can be discussed. But these are perhaps not the most important, the most important, is the big festival as a writer - her cultural consciousness is becoming more and more firm and clear, which is the most admirable and joyful. Discovering and completing a culture's narrative should be a writer's most important mission, and I now believe more and more in this. In the future, if there is a moment when people realize that because of Zhu Wenying's story, people have a lovely legend about Suzhou and About Jiangnan, which is nothing but it, flesh and blood, both form and god, and living, then it is her greatest creation, because it means that she not only wrote the south that lives in the story, but also established herself.

Author: Zhang Qinghua

Editor: Zhou Yiqian

Editor-in-Charge: Zhu Zifen

*Wenhui exclusive manuscript, please indicate the source when reprinting.