Source: Foreign Language Studies, No. 2, 2020

Transferred from: Zhejiang University Translation Academy

Abstract: "Monkey" is the most widely disseminated version in the West among the many English translations of "Journey to the West", and has had a profound impact on Westerners' understanding of this masterpiece of classical Chinese literature. This paper builds on the relevant concepts and principles of the theory of the network of actors, and establishes a theoretical framework by adapting it to the needs of translation research; the University of Reading, Special Collections" "Records of George Allen & Unwin Ltd." The relevant publication materials of "Monkey" are the main data sources, restoring the production process of the translation of "Monkey" in the early 1940s. Describe and discuss the various stages of production of the translation of Monkey, the translation actors involved in it, and how these actors act and make connections in the actual translation activities under real social conditions.

Keywords: Actor Network Theory; Actor; Translation Production; Arthur Welley; Journey to the West; Monkey

START OF SPRING

0. Introduction

This article is guided by the theory of the Network of Actors, based on the University of Reading, Special Collections" "Records of George Allen & Unwin Ltd." A descriptive study of the production process of Arthur Waley's English translation of Monkey: A Folk-Tale of China (monkey) was used as a data source to investigate the applicability of the network of actors theory, explore the stages of translation production, discover the translation actors involved in the production of Monkey,[1] and how they acted and connected in the actual translation activities under real social conditions.

The actor network theory was chosen because of its positive implications for the actual development of translation activities in the study of micros, which is also endorsed by translation scholars such as Buzelin (2005), Chesterman (2006), and Tyulenev (2014); and its use has so far been rare and still needs to be developed. There are many translations of Journey to the West, and many of them are recognized as excellent translations. There are several main reasons for choosing Monkey as the subject of study. One is because Monkey, though not the most faithful, is undoubtedly the most successful — Welley's translation was so beloved in the UK that George Allen & Unwin alone reprinted it six times between 1942 and 1965 (see Johns 1988). Originally published in the UK by George Allen & Unwin, and then published and listed in the United States by John Day, Monkey was equally popular; at the same time, its British translation was once again translated into French, Italian, Spanish, Indian and other languages and spread widely around the world. The second reason is that among the many translations of Journey to the West, only the Monkey has enough historical materials that detail the production process of the translation for research. The third reason is that although there have been many studies of the translation of "Monkey", so far, there has been almost no study of its production process. I also agree with Touri that any translation study without understanding the social environment in which the translation is produced, the actual conditions, and the production process is likely to become a "mere mental exercise leading nowhere" (Toury 2012:22). The research of Bogic (2010) is a good example of how blindly criticizing a translator and translator without understanding the production process of translation may not work and is unfair.

1.The application of actor network theory in translation research: literature review and current situation analysis

Compared with two other theories that also fall under the sociology of translation, Bourdieu's theory of social practice and Luhmann's theory of social systems (Wolf 2007), the use of the network of actors to study the current state of translation activity is not satisfactory. Up to now, there are not many translation scholars and their research results who study the theory of the actor network at home and abroad. Foreign scholars include Hélène Buzelin (2005, 2006, 2007a, 2007b), Andrew Chesterman (2006), Francis R. Jones (2009), Anna Bogic (2010), Esmaeil Haddadian-Moghaddam (2012), Kristiina Abdallah (2012), Sarah Eardley-Weaver (2014), Tom Boll (2016), and Jeremy Munday (2016), among others. Domestic related research started a little later. Relevant scholars include Huang Dexian (2006), Sun Ningning (2010), Wang Baorong (2014, 2017) and so on.

The above studies can be roughly divided into two types. The first is a purely theoretical discussion. Chesterman (2006: 21-23) tentatively proposes that actor network theory can be used to explore the operation of translation activities in reality; Buzelin (2005) and Huang Dexian (2006) introduce actor network theory from a theoretical level and discuss its implications for translation research. The purpose of such studies is to theoretically explain, guide or pave the way for the second type of research. The second type of research takes the actor network theory as the framework and the specific translation project as the research object, collects extensive data, and then completes the study of the translation production process. Buzelin (2006, 2007a, 2007b) first applied the theory of actor networks to study the translation production process. Most of the subsequent studies fell into this category, such as Bogic (2010), Haddadian-Moghaddam (2012), Boll (2016), Munday (2016), and Wang Baorong (2014, 2017).

This study is in line with other studies, but differs from other studies. First of all, this study is empirical in nature and belongs to the second category of studies mentioned above. Secondly, this study selected the English translation of "Monkey" by Wei Li as the research object, focusing on the production process of a specific translation. This is similar to the research angles of Bogic (2010) and Wang Baorong (2014) in the above study. However, the biggest difference from Bogic (2010) is that this article is not limited to discussing the (antagonistic) relationship between translators and publishers, but as far as possible to restore how the participants in various translation projects interact (including conflict and cooperation) under the social and technical conditions of the time, so as to complete the production and dissemination of translations. The most obvious difference between this study and Wang Baorong's (2014) study is that Wang Baorong, like Buzelin and Haddadian-Moghaddam, attempts to place the theory of the network of actors under the same theoretical framework as the theory of social practice. The author of this article still has reservations about whether the theory of the network of actors can be combined with the theory of social practice, so he only uses the theory of the network of actors as the theoretical basis. Finally, on the issue of data collection, the authors of this paper, like Bogic (2010), Boll (2016) and Munday (2016), screen relevant materials from archival historical documents, and at the same time, take the internet search, related literature collection and other methods.

2.Introduction to Actor Network Theory

The theory of the network of actors was born in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and was established by sociologists such as Michel Callon, Bruno Latour, John Law, and others in the course of conducting sociological research in the field of science and technology. Sociologists such as Callon (1986a, 1986b), Latour (1987, 1988, 1999, 2007), and Law (1986a, 1986b, 1992) have introduced and developed the theory of the network of actors. The translation scholars introduced earlier also introduced some important concepts, such as actors, networks, black boxes, etc. This article will not provide a comprehensive introduction to the theory of actor networks, but will only focus on the parts that constitute the theoretical framework of this article.

The main theoretical basis of this paper consists of the basic logic of the actor network theory and the concept of the actor. The basic logic of the network of actors theory is that society is a network system formed in the interaction of various actors; the actors, with their actions, are constantly coordinating and re-coordinating their interrelationships, defining and redefining identities (Callon 1986a), thereby shaping and reshaping society (Latour 2007), rather than, the opposite, by the ubiquitous relatively stable social system or social structure that defines the actor and its actions, relationships, and definitions. This determines that the theory of the network of actors is more concerned with changes and developments, uncertainty, and heterogeneity (ibid.) than fixed static, certainty, and identity. In the theory of the network of actors, all changes, uncertainties, and heterogeneities can be embodied and generated by the actors. It's not hard to understand why Latour proposes that researchers should "follow the actors" and describe how they use actions to build social networks (2007:12,62 etc.). Therefore, the concept of "actor" is particularly important.

Activist network theory scholars argue that "actors" can be both human and non-human (Callon 1986a; Latour 1988, 2007)。 At present, scholars still have a broader definition of "actor", such as Latour (2007: 71) points out that whether a subject, human or non-human, is an "actor" depends on whether he (he) has changed the development of the situation or changed the actions of other subjects, and whether the relevant changes are measurable and verifiable. Few scholars have defined "human actors" and "non-human actors" explicitly. This may be related to the fact that scholars are still looking for and identifying more actors and their agencies, reluctance to specify actors, and reluctance to influence the uncertainty and heterogeneity of actors.

The lack of a clear definition offers more possibilities for research on the one hand, and may blur research boundaries on the other. In this study, how to identify relevant actors became a difficult problem. For example, during the production of translations, translator Arthur Waley and publisher Stanley Unwin[2] relied on correspondence to stay in touch in most cases. Each communication, in addition to two communicators, also requires the cooperation of many people and non-human (messengers, postal carts, etc.) to complete. These people and non-people ensure communication and decision-making between translators and publishers, do contribute to the smooth output of translations, and their actions are verifiable, and letters are evidence, so are these people and non-people actors in translation production? If so, I am afraid it should also include workers who produce paper, printing presses, pigments, printers, etc. As a result, the number of actors can grow almost exponentially, social networks can be extended indefinitely, and translation networks have long ceased to be the center of research. It can be seen that although it is important to understand that the translation network is part of the social network, it is also the key to distinguishing the boundaries between the translation network and the postal network and other social networks. To do this, we should return to the definition of the actors in this translation production.

Therefore, based on the definition of "actor" in Latour, the author proposes another criterion, that is, in this study, translation production actors include only those actors directly related to the translation project (Luo 2018, 2020). Here, "directly related" means directly involved in or directly acting on the production of the translated version. Thus, in the above example, the translator and the publisher are directly involved and directly involved in the production of the translation and belong to the actors of this translation network; Once the definition of "actor" is clarified, it becomes possible to follow the actor to describe the development of the translation network.

In addition, in the process of data analysis, the author uses the "Three Principles" of Callon (1986a: 200-201) and the "Research Methods Guidelines" of Latour (1987: 258) to propose the research guidelines to be followed by the Institute: (1) This research focuses on the analysis of what actions the translators take to produce a particular translation under specific and practical social conditions, rather than how the translation itself or a broad social or cultural background affects the production of the translation ;(2) The author of this article should not make any assumptions about the development of the translation project, the number, variety, behavior, and the way of establishing connections.

3. The Birth of the Welly Edition of the English Translation of Journey to the West in England

Since literature is critical for descriptive research based on the theory of networks of actors, it is necessary to provide a systematic introduction to the literature in this paper. The literature in this article is mainly divided into two parts. The first part is featured by the University of Reading's collection "Records of George Allen & Unwin Ltd." constitute. Materials related to Wyley's translation of Monkey include more than two hundred letters, as well as a number of contracts and a small number of notes. The materials involved many of the actors involved in the translation project, including publisher Stanley Onwyn, David Unwin, who was responsible for printing and production, Arthur Wyley, translator, Duncan Grant, cover designer, and other producers such as printers and bookbinders. These materials record in great detail the production and dissemination of several editions of Monkey and its reprints over a period of about 25 years, between 1941 and 1966. This article intercepts the period from September 1941 to July 1942 and describes and analyzes in detail the production process of the original version of Monkey. Another part of the literature mainly includes the translation of the Monkey (including the preface and the protective seal of the translation), the autobiography of the publisher Aung Van and his writings on the publishing industry, and the articles and works of translators and related translators. This part of the information is supplemented by the first part of the information, providing more material and evidence to support it. In short, this article mainly reconstructs the production process of Monkey based on the correspondence of the participants in the translation project, and uses other literature as necessary to supplement it.

3.1 Free and independent translation space

The author of this article believes that during the translation of Journey to the West, the translator Wei Li has always enjoyed a free and independent translation space. The translation of Journey to the West and the use of translation strategies were decisions and considerations made independently by Willy. First, Stanley Onwy did not commission Welley to translate Journey to the West, but Whley translated the Journey to the West himself, and only proposed publication to Stanley Onwy near the end of the translation; after the translator completed the translation, he delivered it to the publisher for publication opportunities. Previously, Stanley Angwin did not know that Welle was doing the translation of Journey to the West, or even that there was a Famous Chinese book called Journey to the West. This can be inferred from Stanley Onwy's reply to Welly. Stanley Onwyn has stated that in order to be more efficient, the author (or translator) should submit the complete manuscript to the publisher and then review it by the publisher's relevant personnel (Unwin 1995: 9-10). Rather than having other parties assign translation tasks, Welly himself is inclined to suggest that translators should choose their own original text. In an essay on translation, he once stated that free choice of original text helps maintain a translator's sense of mission and passion for translation (Waley 1970: 162-163).

Second, Welly was not a member of the publishing house, and translating Journey to the West was not Welley's full-time job. The entire production of Monkey coincided with World War II, when Welley worked as a censor for the British Ministry of Information. That is to say, Weili is independent of the publishing house in the translation process, and the publisher does not have a substantial influence on the translated text throughout the translation process. In addition, Stanley Onwyn was satisfied with the translation after reading Welley's, and directly proposed the intention to publish, and did not ask for special changes to the translation except for proofreading.

In the eyes of friends, Welly was a quiet, independent, detached scholar, often fully immersed in his own research (Simon 1967, Lewis 1970, Sitwell 1970, Quennell 1970). Walter Robinson recalls, when Wiley wrote Ballads and Stories from Tun-huang, he worked alone in the garden with his manuscripts and simplest tools (Robinson 1967: 61). Welley was accustomed to independent, free work. Such work habits must also affect the translation process of Journey to the West.

In the preface to Monkey, Welly clearly explains why he decided to translate Journey to the West, what translation strategy he adopted, and why he adopted it. Welle (1965: 9-10) considered Journey to the West to be an absurd, humorous, and profound literary work with a rich history and culture, a rare classic; the previous translations were either excerpts and abridgedments, loose paraphrase, or very inaccurate accounts, which led to a retranslation of the book. Journey to the West became very necessary. According to Welley's own account, Monkey selected thirty chapters of the original text, eliminated most of the poems in the selected chapters, and carefully translated the rest, especially conversation and spoken language.

In summary, none of the literature I have collected shows that anyone or department had asked Whillie to make specific changes to the translation. From choosing to translate Journey to the West, how to translate it, to how to revise the translation, all decisions in the translation process are made independently by the translator. This is very different from the case of Bogic's study, when the translator translated Le Deuxième Sexe (The Second Sex) in English, the translation was greatly different from the original due to the influence and constraints of the editor and publisher (see Bogic 2010).

3.2 Rapidly initiated translation projects

Even before Welley could finish translating it, Stanley Onwyn stated that he was "extremely interested" in the progress of the translation of Journey to the West. Within two weeks of receiving Welly's translation, Stanley Onwy completed the review of the translation and immediately wrote to Welly, in which he raised direct questions about the publication. These problems consisted mainly of two aspects, one was to obtain authorization from Welley to publish The Monkey, and the other was to determine the form in which the translation would be published.

Willy has worked with Stanley Onwyn on several occasions. In the more than two decades from 1919 until the publication of Monkey, Welley published about 28 books, half of which were published by Stanley Onwyn's publishing company (see Johnson 1988). Knowing this fact, it is not difficult to understand that Stanley Onwy could draw a contract between the publisher and Welley on the terms previously agreed upon by the two parties. From the drafting of the contract to the signing of the Werley authorization, Stanley Onwy took only ten days.

It is much more difficult to determine the form of publication of a translation than to obtain authorization to publish a translation. Although the available literature does not show whether Stanley Onwyn elaborated on the publication of Monkey, it is certain that he took into account the publishing environment at the time and the policy restrictions on the production of translations. Stanley Onwyn was puzzled at how to present such a beautiful, absurdly humorous translation in the "best form." At the time of World War II, the shortage of resources had created many problems for publishers, and the British government had introduced some policies to restrict the publishing industry (Holman 2008), which made it more difficult to produce beautiful translations. To this end, Stanley Onwynjovely talked in detail, and soon accepted David Aungwey's advice, deciding to abandon the use of Katsushika Hokusai's ukiyo-e Journey to the West illustration and find a chinese artist to design Avery's translation. However, the question of the form of the translation was not thus resolved. For a long time after that, more and more people participated in the design and production of "Monkey". [9]

3.3 Well-conceived translation design and proofreading of translations

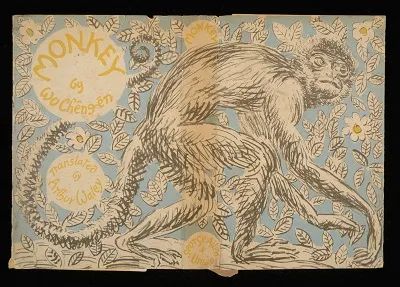

Stanley AungWin asked Welly to recommend a Chinese artist to design the seal and title page for Monkey. Among the Chinese artists in London at the time, Welly only knew Jiang Yi, and Welley did not like his work. So Welley took the opportunity to recommend the British artist Grant. On the one hand, Wiley wanted Grant to be free to use his imagination in the design; on the other hand, as Welly's friend, Grant could give a reasonable asking price.

Stanley Onwyn immediately wrote to Grant, in which he outlined the situation and attached a passage from Werley describing the general contents of the translation. At the same time, Welle also wrote to ask Grant to design the translation. Grant accepted the couple's invitation and agreed to design the cover and title page of Monkey at the market price of the publishing industry at that time.

After successfully hiring Grant as the designer, Stanley Onwyn seems to have handed over the rest of the production to the publishing house's production department. David Angwin, in charge of the production department, was responsible for the typesetting and printing of the translations. He believes that Monkey is a book with a difference, not only needing a beautiful cover, but also a redesigned layout specifically for the translation. By mid-November 1941, David Onwy had prepared two sets of typography, one for the usual design and the other for new designs, and sent them to Ville for comment.

About a month later, the production department sent Copies to Welly for proofreading. [14] Grant was then sent all the proofs for him to learn about the story, as well as some other requirements besides the design patterns, such as the size of the seal and the title page, and the types of colors available.

Welley completed proofreading in late January 1942. He wrote to Stanley Aung-Win asking about Grant's design progress. Previously, Stanley Onwyn had not given Grant any time limit. Upon learning that Willy had completed the proofreading, David Onwyn urged Grant to get the title page design first. Grant promised to complete all the design work next Monday, but he had to consult Welley before handing it over.

Although Grant quickly completed the original design, the design phase was far from over. Publishers need to convert these design manuscripts (which participants call "reproduction") into final samples for direct use in printing. This process of "reproduction" is full of uncertainties and can be described as twists and turns. There have been iterations of changes to the original, the choice of cover cloth and sample color, and the production method of the sample. The following discussion focuses on two changes to the original manuscript.

The first changes were made by the publisher. Both Stanley Onwing and David Annwin were pleased with Grant's original design. However, considering the peculiarities of Monkey, they wanted the monkey pattern on the seal to be reversed head to tail, so that the head of the monkey coincided with the front of the book, and the tail of the monkey and information such as the title and translator of the book were transferred to the back of the book (Wu 1965). Grant gave a simple explanation of his original design—the monkey's tail appeared on the front of the book in line with the rebellious character of the Chinese monkey (Sun Wukong), but still left the final decision to the publisher.

With the technology of the time, it was not easy to make a sample according to the original design of the seal. The person in charge of carving the template privately altered the original manuscript and repainted Grant's design, resulting in a simplified pattern in the resulting sample. This simplification is a much more substantial change than the first substitution of the first pattern. Grant felt that the simplified pattern did not match his original design, so he was reluctant to use the simplified pattern. Although eager to enter the next round of production as soon as possible, the publishing house also decided to abandon the simplified sample and make a new sample according to the original after finding out the facts. After many efforts, the new sample draft of the seal was finally completed at the end of April. This meant that printing with the new sample was about two months later than printing with the simplified sample.

3.4 Delayed publication: printing and binding of translations

The printing of the translation went relatively smoothly, and there was no delay in publication due to a lack of paper due to the printing of the fourth edition of Monkey at the end of 1943. Nevertheless, during the translation binding phase, publishers had to postpone publication from the original 9 July to 23 July, as the bookbinders were unable to complete their work on time. Fortunately, the publisher did not suffer losses due to the delay in publication date, but had more time to prepare inventory and supply, and it was possible that Monkey would have a related book review at the time of publication, thus playing a promotional effect.

In summary, the production process of Monkey can be roughly divided into six stages, namely the translation of text [19] (<[20] 1941.10), the initiation of the translation project (1941.10-11), the design of the translation (1941.11-1942.5), the proofreading of texts (1941.12.18-1942.1.21), the printing of translations (1942.5-6), and the binding of translations (1942.6-7). During the translation phase,[22] the translator Willy translated Journey to the West into English as Monkey. During the project launch phase, publisher Stanley Onwyn evaluated and decided whether to publish Monkey and planned how to make the translation stand out under limited conditions. During the translation design phase, artist Grant designed the cover and title page of Monkey, and David Angwin, who was in charge of printing, designed the typesetting of Monkey. At the same time as the design, the translator independently and efficiently completed the proofreading. Finally, printers and bookbinders print all the sheets and covers of the translation and bind them into a book. On the whole, the above six stages occur sequentially. However, the proofreading phase takes less time and the design phase takes longer, so the proofreading phase completely coincides with the design phase in time, and starts later than the design phase and ends before the design phase. (See Figure 1)

Figure 1: The six stages of the production process of Monkey and the main human actors

4. Conclusion

This paper uses the basic logic, related concepts and research criteria of actor network theory to construct a theoretical framework for descriptive research on translation production processes. Within this framework, a descriptive study of the production process of the English translation of Monkeys from Journey to the West was conducted. The study found that: (1) Unlike many classic translations, "Journey to the West" is selected by the translator himself and translated independently, in the translator's own words, which makes him full of interest and passion for translation, and can ensure the quality of translation. (2) The most important actors, namely translators and publishers, are extremely concerned about the design of translations. Translation design is arguably the most difficult and tortuous action in the production stage, involving complex actors, many conflicts of interest, and the longest time consumed in the production process. (3) The production process of the translation is full of uncertainties, for example, the original manuscript has been simplified privately, and the binding office no longer supplies the designer's original selection of lilac cover cloth. These factors continue to weave and update the network of translation production in unexpected ways, and they also constantly change and ultimately shape the face of translation. (4) The production process of Monkey can be roughly divided into six stages, each of which has different actors collaborating to achieve a specific purpose. (5) In addition to translators and publishers, translation actors include designers, engravers of design templates, printers, staplers, etc., each of whom has a greater or lesser influence on the production of the translation and the translation itself, and as noted above, these effects are difficult to predict in many cases. In short, translation is not just as simple as the translator completing the translation work and the publisher producing the translation, but the influence of other actors (such as designers and template engravers) and their related actions on the production process and results of the translation should not be ignored, otherwise both the translation activity and the study of the translation itself are one-sided.

Finally, it must be noted that describing the production process of translation is not an end in mind, but a preparation for more in-depth research. For example, how the various translation actors coordinate their interests and work together to complete the publication of The Monkey through obligatory passage points; how the actions of the translation actors and their relationship with other actors affect their own roles and identities in translation activities; what kind of actions non-human actors produce in the production process of the Monkey, what kind of initiative they have, and how they have for other actors? The production of the translation and the impact of the translation itself are urgently needed to be discussed. The author hopes to present the research results of the above problems in future articles, and also hopes that more translation research colleagues can use the actor network theory to study translation cases. Only by accumulating a large number of in-depth case studies can we better realize the common development of actor network theory and translation activity research.

Fund Projects: Some of the research results of the project funded by the China Scholarship Council (No. : Liu Jinfa [2013] 3009).

Notes

1. Due to space limitations, the term "participants" referred to in the text includes only the "human actors" referred to in the theory of the network of actors. I am writing in translation as Actor-Networking, A Lierary Translation as a Translation Project, and another journal article (Visiting elements thought to be 'inactive': non-human actors in Arthur Waley's Non-human actors are discussed in detail in the translation of Journal to the West.

2. All references to Stanley Onwing and David Aungwyn are referred to by full name in the whole text to distinguish between them.

3. Stanley Onwy's letter of 25 September 1941 to Welly (Records of George Allen & Unwin Ltd., UoR AUC 127/7).

4. Stanley Onwy's letter of 22 October 1941 (Records of George Allen & Unwin Ltd., UoR AUC 127/7).

5. Interestingly, Journey to the West is the only Chinese novel translated by Welly. Welly is good at translating Chinese poetry into English, and before translating Journey to the West, Welly was already a well-known sinologist and translator. His works are mainly translations of ancient Chinese poetry, with classics such as A Hundred and Seventy Chinese Poems (1918) and The Book of Songs (1937) (see Johnson 1988).

6. Records of George Allen & Unwin Ltd., UoR AUC 127/7, 25 September 1941.

7. Records of George Allen & Unwin Ltd., UoR AUC 127/7, 22 October 1941.

8. Ibid.

9. Stanley Aumwyn's letters of 22 and 31 October 1941 to Welly (Records of George Allen & Unwin Ltd., UoR AUC 127/7).

10. Stanley Aung-Win's letter to Welly of 31 October 1941 and Welley's reply to Stanley Angwin of 3 November 1941 (Records of George Allen & Unwin Ltd., UoR AUC 127/7).

11. Stanley Aumwin's correspondence with Grant on 7 November and 9 November 1941 (Records of George Allen & Unwin Ltd., UoR AUC 112/19).

12. Records of George Allen & Unwin Ltd., UoR AUC 127/7, 14 November 1941.

Letter from production department to 18, 19, 24, 30 December 1941 (Records of George Allen & Unwin Ltd., UoR AUC 127/7).

14. David Aumwin's correspondence with Grant on 1, 4, 6 January 1942 (Records of George Allen & Unwin Ltd., UoR AUC 138/5).

See the correspondence between Welly and Stanley Onwy, David Onwy and Grant from 20 to 23 January 1942 (Records of George Allen & Unwin Ltd., UoR AUC 154/4, UoR AUC 138/5).

See Records of George Allen & Unwin Ltd., UoR AUC 138/5, 28 January, 1942, 1 February 1942.

See Letter from the Ministry of Production to Grant of 3 March 1942 and Grant to David 26, 1942 (Records of George Allen & Unwin Ltd., UoR AUC 138/5).

See Welly's letter to Stanley AUC of 22 and 23 December 1943 and Records of George Allen & Unwin Ltd., UoR AUC 181/1, UoR AUC 154/4.

19. Text and translation have different meanings in the text. Text refers to the textual content of a translation, which includes the translated text and its sub-texts, emphasizing its own integrity.

20. The symbol < in the text means "at least" or "before (a certain period of time)".

21.There are not many records of the printing and binding stages of the translation, nor are there any definite signs or dates of commencement and end. The temporal division of these two phases is inferred from the publication time of Monkey and the antecedents and consequences of its changes.

22.This translation project also includes two other phases: marketing (< 1942.9, < 1943.2, < 1944.4, <1946.7) and translation dissemination (< 1942.1-1966). Due to space limitations and the fact that the marketing and dissemination of the translated version does not directly affect its production process, these two stages are not discussed in this article.

bibliography

Huang Dexian. 2006. The networked existence of translation[J].Shanghai Translation (4):6-11.

SUN Ningning. 2010. The cultivation of translators in theory and application of actor network[J].Research and Practice of Higher Education(2): 47-49.

Wang Baorong. Sociological analysis of the production process of Ge Haowen's English translation of "Red Sorghum"[J].Journal of Beijing Second Chinese University(12):20-30.

Wang Baorong. Sociological analysis model of Chinese literary translation in the West[J].Journal of Tianjin University of Foreign Chinese (4):1-7.

[5] Abdallah, K. 2012. Translators in Production Networks: Reflections on Agency, Quality and Ethics [D]. Dissertations in Education, Humanities, and Theology. Joensuu: University of Eastern Finland.

[6] Bogic, A. 2010. Uncovering the hidden actors with the help of Latour: the ‘making’ of The Second Sex[J]. MonTI. Monografías de Traducción e Interpretación, Sin mes: 173-192.

[7] Boll, T. 2016. Penguin Books and the translation of Spanish and Latin American poetry 1956-1979[J]. Translation and Literature25: 28-57.

[8] Buzelin, H. 2005. Unexpected allies: How Latour’s network theory could complement Bourdieusian analyses in translation studies[J]. The Translator 11 (2): 193-218.

[9] Buzelin, H. 2006. Independent publisher in the networks of translation[J]. TTR: Traduction, Terminologie, Redaction19 (1): 135-173.

[10] Buzelin, H. 2007a. Translations “in the making” [C]// M. Wolf & A.Fukari.Constructing a Sociology of Translation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins: 135- 169.

[11] Buzelin, H. 2007b. Translation studies, ethnography and the production of knowledge[C]// P.St-Pierre & P.C.Kar. In Translation – Reflections, Refractions, and Transformations. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins: 39-56.

[12] Callon, M. 1986a. Some elements of a sociology of translation domestication of the scallops and the fishermen of St Brieux Bay[C]// J.Law. Power, Action and Belief. A New Sociology of Knowledge? London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Books: 196-233.

[13] Callon, M. 1986b. The sociology of an actor-network: the case of the electric vehicle[C]// M.Callon, J.Law & A.Ri.Mapping the Dynamics of Science and Technology: Sociology of Science in the Real World. London: The Macmillan Press: 19-34.

[14] Chesterman, A. 2006. Questions in the sociology of translation[C]// J.F.Duarte, A.A.Rosa & T.Seruya. Translation Studies at the Interface of Disciplines. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins: 9-27.

[15] Eardley-Weaver, S. 2014. Lifting the Curtain on Opera Translation and Accessibility: Translating Opera for Audiences with Varying Sensory Ability [D/OL]. UK: Durham University. http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10590/ [2016-04-10].

[16] Haddadian-Moghaddam, E. 2012. Agents and their network in a publishing house in Iran[C]// A.Pym & D. Orrego-Carmona. Translation Research Projects 4.Tarragona: Intercultural Studies Group: 37-50.

[17] Holman, V. 2008. Print for Victory: Book Publishing in Britain 1939-1945[M]. London: British Library.

[18] Johns, F. A. 1988.A Bibliography of Arthur Waley[M]. 2nd ed. London: The Athlone Press.

[19] Jones, F. R. 2009.Embassy networks: translating post-war Bosnian poetry into English[C]// J. Milton & P.Bandia. Agents of Translation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins: 301-325.

[20] Latour, B. 1987. Science in Action. How to Follow Scientists and Engineers through Society[M]. Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press.

[21] Latour, B. 1988. The Pasteurisation of France[M]. tr. A.Sheridan & J.Law. Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press.

[22] Latour, B. 1999.On recalling ANT[C]// J.Law & J.Hassard. Actor Network Theory and After. Oxford: Blackwell: 15-25.

[23] Latour, B. 2007. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network- Theory[M]. New York: Oxford University Press.

[24] Law, J. 1986a. On power and its tactics: a view from the sociology of science[J]. The Sociological Review34(1): 1-38.

[25] Law, J. 1986b. On the methods of long distance control: vessels, navigation and the Portuguese route to India[C]// J.Law. Power, Action and Belief. A New Sociology of Knowledge? London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Books: 234-263.

[26] Law, J. 1992. Notes on the theory of the actor-network: ordering, strategy, and heterogeneity[J]. Systems Practice5(4): 379-393.

[27] Lewis, N. 1970. The Silences of Arthur Waley [C]// I.Morris. Madly Singing in the Mountains. An Appreciation and Anthology of Arthur Waley. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.: 63-66.

[28] Luo, W. 2018. A Literary Translation as A Translation Project: A Case Study of Arthur Waley’s Translation of Journey to the West [D]. UK: University of Durham.

[29] Luo, W. 2020. Translation as Actor-Networking: Actors, Agencies, and Networks in the Making of Arthur Waley’s English Translation of the Chinese ‘Journey to the West’[M]. New York: Routledge.

[30] Munday,J.2016.John Silkin as anthropologist, editor and translator[J]. Translation and Literature 25: 84-106.

[31] Quennell, P. 1970. A note on Arthur Waley[C]// I.Morris. Madly Singing in the Mountains.An Appreciation and Anthology of Arthur Waley. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.: 88-92.

[32] Robinson, W. 1967. Dr. Arthur Waley[J]. The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland1 (2): 59-61.

[33] Simon, W. 1967. Obituary Arthur Waley[J]. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies30 (1): 269-271.

[34] Sitwell, S. 1970. Reminiscences of Arthur Waley[C]// I.Morris. Madly Singing in the Mountains. An Appreciation and Anthology of Arthur Waley. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.: 105-107.

[35] The University of Reading. Records of George Allen & Unwin Ltd.[C]. Special Collections.

[36] Toury, G. 2012. Descriptive Translation Studies and Beyond[M]. Revised edition. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

[37] Tyulenev, S. 2014. Translation and Society[M]. London and New York: Routledge.

[38] Unwin, S. 1960. The Truth about a Publisher: An Autobiographical Record[M]. London: George Allen & Unwin.

[39] Unwin, S. 1995. The Truth about Publishing[M]. New York: Lyons & Burford.

[40] Waley, A. D. 1970. Notes on translation (1958)[C]//I.Morris. Madly Singing in the Mountains. An Appreciation and Anthology of Arthur Waley. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.: 152-164.

[41] Wolf, M. 2007. Introduction: The emergence of a sociology of translation[C]//Wolf, M. and Fukari, A. (eds.). Constructing a Sociology of Translation. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins: 1-36.

[42] Wu, C. 1965. Monkey: A Folk-Tale of China[M]. tr. A. D. Waley. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

About the Author

Luo Wenyan

He is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University and graduated from the University of Durham in 2019 with a PhD in philosophy. His research interests include sociology of translation, history of translation, and translator research.