Professor Yang Jing of the School of Foreign Chinese of Nanjing Normal University

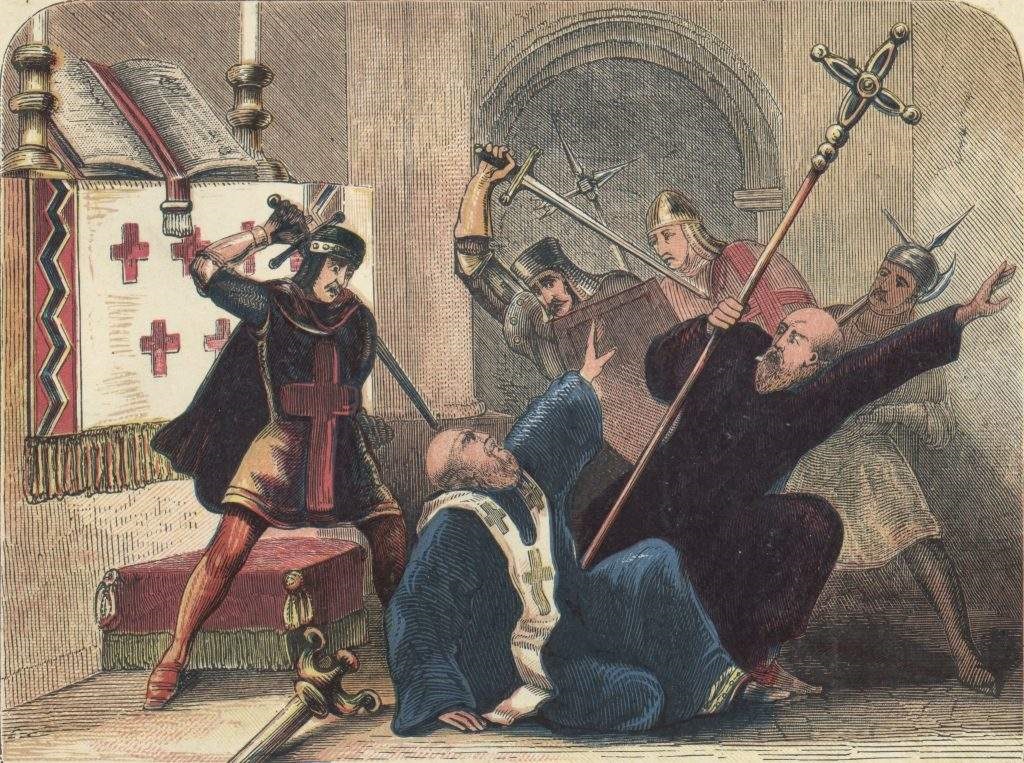

Thomas Beckett was killed

In 1927, T.S. Eliot borrowed the words of historical figures in his famous poem "Journey of the Magi" to ask the soul: "Man grows a long way, and we search up and down, is it to survive or die?" Eight years later, the poet responded in the poem Murder in the Cathedral: the "true saints" of history, such as the protagonist Thomas à Becket (1118-1170), in order to "defend the (Church) truth", not only did not fear death, but even dared to "die". Even more amazing is that two years after Becket's death, Pope Alexander III ordered him to be posthumously canonized, thus setting a record for the fastest canonized in the history of the Church of Rome.

In 1935, the literary critic G. Chesterton K. Chesterton) and the poet W. Chesterton B. Yeats was invited to watch the premiere of Elliot's poetry at the Mercury Theatre. Chesterton, who was known as the "Prince of Paradox", summed up the play in Wilde witticisms as usual: The king sent four killers into Canterbury Abbey — "where they killed a traitor, but there was one more saint in the world.". The historical event of Beckett's sanctification was first seen in Chaucer's Canterbury Tales. The book describes the pomp and circumstance of the pilgrimage of the nations as follows: "Believers from all over the country, north and west, and the multitudes rushed to Canterbury in return for the savior of the world and to remember the saints of great grace. Of course, in addition to expressing admiration and reverence, there are also practical interests in the worship of the saints - the church monks collect the blood and water flowing at the time of Beckett's martyrdom and put them into a lead "holy bottle" called "the water of St. Thomas", and the bottle body is engraved with the words "Thomas is a virtuous doctor of good character" and sold to pilgrims - it is said to be "curative of all diseases". Like Jane Austen's English hot springs with "miraculous curative properties", the "holy land" of Canterbury has a reputation that has attracted countless pilgrims from their own countries as well as France and Italy.

In 1538, Henry VIII broke with the Holy See, and the "obscenity" of St. Thomas was repeatedly forbidden, so he ordered that "his holy name be revoked and his remains destroyed", but this move was ultimately difficult to resist the piety and enthusiasm of the fool and the fool. After the death of Henry VIII, the chapel dedicated to the Eucharist of Thomas was restored, and the pilgrimage winds returned and intensified. Until the eighteenth century, the Enlightenment thinker David Hume was so distressed by this that he commented in the History of England (1754): "Every year more than 100,000 pilgrims go to Canterbury to pay homage to the grave of the archbishop. The heart of a good name... It is sad that such a response has been generated. The greatest genius of enlightened mankind is admired far less than this impostor saint, whose deeds are abominable and despicable, whose tireless pursuits are aimed only at the scourge of the people. ”

The question, then, is why did the archbishop, who was hailed as a moral gentleman by the ecclesiasticals, be denounced by enlightenment scholars as a well-known "fake saint"? What was the far-reaching "Becket's Dispute" in British medieval history?

Becket was a second-generation French immigrant, born into a merchant family in London. He studied at Merton Abbey in his early years, then went to Paris to study, where he returned as a clerk to Theobald, Archbishop of Canterbury. In the eyes of his contemporaries, Becket was "intelligent, charismatic, and majestic", and was deeply appreciated by the archbishop, and was soon promoted to the position of archdeacon of the cathedral. In 1155, Becket ushered in the most important opportunity of his life - on the recommendation of the Archbishop, King Henry II appointed Becket as the Archbishop of England, and then as Privy Councillor, thus embarking on a "honeymoon journey" between monarchs and courtiers.

Henry II succeeded to the throne in 1154. Prior to this, he had acquired Normandy, Anjou and Aquitaine through succession and marriage, creating the Angevin empire, which spanned the European continent and the British Isles. As the founder of the Plantagenet dynasty, Henry II was a man of great talent and was known for meritocracy. At the beginning of his reign, like his ancestors, he spent most of his time in Normandy, paying more attention to European affairs, and regarded England as his granary in the rear of Europe. The king is fluent in six languages, including French, Italian and Latin, but does not speak English! Therefore, he also urgently needed Beckett, a powerful minister from a humble background, to act as a "spokesman". The king was already dissatisfied with the aristocratic family, who, in his "ancestral shadow", actually roared in the courtroom, "If there were no barons desperately moving forward, the illegitimate son William would never have conquered England!" Beckett was the first Aboriginal to be elected to the Lord's Court, but not the last. The king wanted to take the opportunity to suppress the arrogance of the nobles who were born on their own.

Of course, the more powerful church was the thorn in the king's flesh than the arrogant aristocratic community. The former can be bought or divided and disintegrated through subordination and rewards, while the latter is monolithic: from bishops to popes, everyone claims to oppress god and attempts to usurp or even override the king's power. The conflict between clerical and royal power in Europe has a long history, especially since the "Cluniac Reforms" initiated within the Church of Rome in the tenth century, the influence of the Church in the Western world has increased greatly, and "papal power has begun to transcend the boundaries of various feudal lords and races, nationalities, and languages, indicating the universality of papal power." In 1076, Pope Gregory VII forced the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV to kneel by issuing a "excommunication order", which frightened the monarchs of Europe.

One of the results of the Cluny Reformation was the concoction of the myth of "ecclesiastical freedom," the existence of a kingdom of heaven above secular power governed only by God's "law." This also meant that the ecclesiastical property of the Church was sacrosanct, that the clergy were not appointed by royal decree, and that the sins committed by the clergy were not subject to the jurisdiction of the Kingdom. According to historians, at the beginning of the Reformation, church freedom in England was still a "negative freedom" (from royal power), but it rapidly expanded into a "positive freedom" after Anselmus (1033-1109) was elected Archbishop of Canterbury: it called for the naturalization of the Church of England into the universal Church under the papacy, and the transformation of the Church of England according to Pope's Bull Decree, thus forming an "independent kingdom" headed by the Archbishop of Canterbury from top to bottom All matters are "handled by family law" according to doctrinal canon law, and the procedures are not revealed, and the judicial system of the kingdom cannot intervene at all. Under the banner of "protection of clerical property", the trade in the priesthood, corruption and bribery, and the plundering of wealth prevailed: the promotion of the priesthood was directly related to the power, political status and economic interests of the clergy—the clergy of that time could hold several positions, all of whom enjoyed the holy goods, and did not have to live in the corresponding parish, as in today's "empty pay" (Pope Alexander III tried to reform, but because there were too many people who profited from it, the law did not blame the people, and it was dismissed). In fact, under the umbrella of "ecclesiastical freedom", the interior of the church has decayed to the point that people lament that "there is nothing in the whole of Europe that indicates the existence of the monks except the shaved heads and robes of the monks".

The king wanted to rely on Beckett's talents to limit the expansion of the church's power, and the latter did not disappoint the king. After taking office, Becket defended the interests of the crown in a tough manner, forcibly confiscated disputed ecclesiastical estates, forced priesthoods in the diocese to be recommended and appointed by feudal lords (royal vassals), and severely punished those who refused to obey. It is said that Archbishop Theobald, who had recommended Beckett's "entry" to the throne, was furious when he heard the news and called him a "traitor" - the archbishop's original intention was to send him into the enemy's interior to secretly defend the rights and interests of the church.

At the same time, however, Becket was also deeply favored by the king: not only was he good at drafting edicts, but he was also rewarded with a huge fortune of hundreds of millions of dollars- and soon the king even entrusted all the manor property under the royal family's name to this confidant minister, which showed the prosperity of the holy family. The close relationship between the two is described by the French historian Augustin Thierry in The History of the Conquest of England by the Normans (1825): "Becket was Henry II's most loyal and intimate companion, who dined with the king, entertained, and even had the right to enjoy the king's gold and silver jewelry." Like the historical proprietors, Beckett was adept at amassive and good at spending. On one of his visits to France, there were hundreds of honor guards alone, far ahead of the average king on the European continent. Such a high-profile act inevitably aroused the indignation of the nobles, but it undoubtedly further won the king's favor.

In 1162, the post of Archbishop of Canterbury became vacant and the King decided to be succeeded by Becket. According to ecclesiastical tradition, the post must be elected by high-level meetings within the Church convened by the bishops and abbots of the major (district) (district) –given Becket's lifestyle and academic reputation (he was particularly lacking in theological knowledge), it was clear that normal elections would not yield satisfactory results. Before the council, the King issued an edict that if the elections did not go as he wished, Canterbury would henceforth become an enemy of the Kingdom of England. Proceeding from conscious obedience and service to the overall political situation, the top echelons of the church gave up resistance. In May of the same year, Becket was made Archbishop. In June, the coronation and consecration ceremony was officially held. The king was satisfied, but he did not know that, as he would later lament to his courtiers, that his "nightmare had only just begun."

Perhaps from the moment he stepped into the cathedral, Beckett was determined to be "sanctified." His first astonishing act was not to disobey the king's wishes, and he resigned categorically as a lord of the kingdom on the grounds that "one servant cannot do two masters" (coincidentally, Thomas More, who was martyred three hundred years later, paid tribute to Henry VIII for the same reason). The king, though unhappy, agreed to his resignation because of his past feelings—beckett did not seem to realize that the matter had created a gap between him and the king that could never be repaired.

What shocked the king even more was that Beckett, who had always been extravagant, was unusual after taking office. His private life became unusually simple: he was dressed in coarse cloth and linen, and fed only vegetables, grains and water every day. There is no other hobby than studying scripture day and night. Particularly commendable is that he not only regularly flogged himself, but also imitated Jesus Christ's insistence on washing the feet of thirteen beggars daily. Soon, the name of the archbishop's holy piety spread far and wide, all the way to the Holy See. With the acquiescence and encouragement of the latter, Becket began to openly disobey the royal power and vigorously defend the privileges of the church - from a loyal royal guard to an "enemy of the king", successfully completing another gorgeous "rebellion" in his life. The change occurred almost overnight, and Beckett boasted that it was "a great change by the hand of God."

As "the two mighty cattle pulling the heavy plough of England", the theocratic dispute between the king and the archbishop is very extensive, but the core of it is undoubtedly the "problem of the crime of the clergy". In 1163, vicious incidents in Belford, Winchester, and London were all related to the clergy—among them, a priest in Winchester abducted the daughter of a gentry, and after being opposed by the woman's family, he did not stop and killed his father, which was appalling. In fact, since Henry ascended the throne, there have been about a hundred murders involving clergy; there have been countless cases in which clergy have been charged with robbery or theft. However, the vast majority of these cases were heard by the ecclesiastical courts without a just outcome – with Beckett's forceful intervention, the Three Clergy cases were subsequently referred to the inquisition and were dismissed.

It is precisely because of the exclusive judicial immunity enjoyed by church people that the "attractiveness" of the church has increased greatly: all kinds of idle people in society, such as hooligans and villains who can be mixed into church organizations through bribes (and pay a small membership fee), can be mixed into church organizations and receive holy gifts, not only have no worries about food and clothing, but also can be used as a blessing, and for a while many people are competing for it - according to incomplete statistics, the number of church members in the heyday accounted for nearly one-sixth of the total population of Britain, which is staggering. History records that a group of evildoers were hidden in a monastery in Hamptonshire, who went out irregularly to rob merchants passing by, and then escaped as clergy— the "priesthood" of the church was transformed into a "talisman" for all the most evil people, and the church itself became the abyss of sin.

Long before Henry II ascended to the throne, the people of the country had suffered from the church and complained that the people's dissatisfaction was mainly due to the protection and protection of the ecclesiastical court. It is well known that the secular regimes of medieval Europe were known for their severe torture, and that arsonists and thieves were often not allowed to die, but the Inquisition, in the name of God's benevolence, gave leniency to members who had also committed serious crimes: either by imprisonment in lien with the monastery, or by condemning them to join the Crusades, or at best by expulsing them from ecclesiastical organizations. They are all citizens of the same country, but they cannot enjoy equal treatment; the difference between the inside and outside of the church is so obvious that it is not fair and just, and it is even more difficult to block the mouths of the people. In order to control public opinion, the church authorities have also invented a false charge of "blasphemy" in an attempt to prohibit all slander and nonsense in the name of "sacredness," thus increasingly arousing the hatred and disgust of the people.

The king could not turn a blind eye to this. The king studied law from an early age, and according to the famous American medieval historian Bryce Lyon, Henry II was the "great reformer of the law" and the "true founder" of English common law—he abolished the law of duels, the law of oath of exoneration, and the extremely barbaric law of divine inquisition; he appointed circuit judges, introduced a jury system, and worked to abolish the judicial privileges of the aristocratic and clergy classes—during his tenure, English common law (case law) matured and became a model for future generations to emulate. As Churchill put it in A History of the English-Speaking Peoples (1956-1958): "Among the kings of England there were soldiers more outstanding than Henry II, and diplomats more aversaries than he was, but no one could match him in terms of legal and institutional contributions." ”

After careful planning, in early 1164 Henry II presided over a special meeting to launch a counterattack against Becket. The Council adopted the Constitution of Clarendon (herein referring to a set of judicial principles and established customs) that legally confirmed the power of the King of England over the Church since the Norman dynasty, with the core issues concerning the appointment of the priesthood and the treatment of priesthood crimes. Becket was caught off guard at the meeting, forced to sign his consent, and immediately repented, writing his grief and indignation as Miza petitioning the Pope for "Holy Judgment".

In the clash between church and state, as the Pope's envoy in England, Becket took it as his duty to defend the rights of the Church and always adhered to the supremacy of the Pope: "In any case, the laity cannot become the judge of the clergy. If the priest had any offense, he should be corrected in the ecclesiastical court. In response to Beckett's view, the law-savvy king believed that the priests should receive honors higher than the laymen, and that they should have higher moral conduct, but that crimes were inferior to those of ordinary laymen, and that they should be severely punished, which was also the meaning of equal rights and responsibilities. In this regard, Beckett was speechless, and could only sacrifice the "Supreme Magic Weapon" to fight against it. For a clergy, he argued, dismissal and stripping of a priesthood were "the heaviest punishments." To be judged by secular courts again is against the "way of God"—because the Bible says that one should not be punished for one sin and two punishments. In fact, until his exile in France, Becket insisted in his letter to the king that "you have no right to rule over bishops, you have no right to take priests to secular courts for trial, and Almighty God wants Christian priests to be judged by bishops, not by secular authorities." - It's really obsessive and unrepentant.

According to historical records—the poet Alfred Tennyson had a very eloquent portrayal of this in the historical drama Becket (1884)—in order to ensure the stability of the church-state relationship, the king initially had the intention of reconciliation, and summoned the archbishop in the Chamber of Secrets and played against him. "You have trapped your king," Henry II reminded meaningfully. But Beckett was indifferent— he "died" of the king and set the stage for his tragic fate.

At the behest of the King, the King's Bench ordered Minister Becket to appear for trial in the name of "corruption" during his tenure, and provisionally added a charge of "Foreign Lyton" to the trial — under the Clarendon Charter, church members were not allowed to contact the Holy See without the King's permission. The economic affairs were small, the crime of treason was great, and Beckett saw that the opportunity was not good, so he could only choose to flee in a hurry, and did not forget to write a letter to the Pope on the way to escape.

At that time, the Holy See was mired in internal strife, and the Pope urgently needed Henry II's financial support, so he knew that Becket was suffering "political persecution" and could not do anything, but could only mediate between the two sides. During this period, there were several peace talks between the two sides, but due to the archbishop's firm stance and refusal to back down slightly, the king's delegation repeatedly failed to return, and the negotiations reached an impasse. The turning point in peace talks came in 1170. In June of that year, in view of the Archbishop of Canterbury's exile, Henry II ordered the coronation of the young king by Archbishop York, the second in command of the Church, which in Becket's view was undoubtedly a blatant provocation to the church's traditions and his own authoritarianism. Becket appealed to the Pope, and Henry II was forced to agree to reopen peace talks. Eventually, the king promised to reinstate Becket as Archbishop of Canterbury and to guarantee his personal safety upon his return to England, provided that Beckett did not punish the churchmen who presided over and participated in the coronation.

In early December, Beckett returned to London amid the cheers of the people. He felt that he had the support of the people and had the pope's special blessing, which was enough to compete with the king, so he brazenly ordered the expulsion of the Archbishop of York and the other three people. The three bishops cried to the king, who was so enraged that he shouted on the spot, "Who can help me get rid of this troublesome priest!" ”(“will no-one rid me of this troublesome priest?” The four knights at the king's side crossed the English Channel overnight and rushed to Canterbury Cathedral to kill Becket. It is said that at the time of his previous sermons, Becket had foreseen his fate, but he did not choose to defend himself, nor did he heed the advice of his subordinates to hide in the cathedral (holy place). Faced with a royal power that even the Pope could not help, he felt that he might only die to defend the privileges of the Church.

This is also the correct assessment of him by historians: "Becket's knowledge could not help him to propose original ecclesiastical policies and reform programs, and to quickly establish his prestige, he chose to show a certain tough posture in the relationship between the sacred and the secular." All of Beckett's measures boil down to the same purpose of relieving the crisis of legitimacy of his power in the short term. According to Eliot's poetry, it was Beckett's "pride and ambition" that led to his demise. The French dramatist Jean Anouilh, who commented in his play Becket ou l'Honneur de Dieu (1959): "To be a saint is also a temptation — a temptation that is indeed difficult for an ambitionist like Becket to resist." ”

But for the Church of Rome and its adherents, Becket died a good death. Historian Hilaire Belloc once described the enormous impact of Beckett's death this way: "The tide of public opinion was rapidly reversed—in less than an hour St. Thomas became a martyr; in less than a month, he became not only a defender of religion, but also a guardian of ordinary people (the patron saint of London). These commoners, though somewhat ignorant, firmly believed that the standing of the Church was a solid guarantee for them under the oppression of the crown. ”

Caught off guard, Henry II, after three days and three nights of hunger strikes, decided to compromise with the church. He went to the cathedral to plead guilty and promised to atone for the archbishop's death by the following measures: the king promised to forgive all those exiled for supporting the archbishop and to return their lands. Return all property of the Diocese of Canterbury since ancient times. The King paid a sum of money to the Knights Templar each year to finance the pilgrimage of two hundred knights to the Holy Land. Henceforth, the king may not enforce charters that undermine the prerogatives of the Church, and may not prevent clergy from appealing to the Pope on ecclesiastical affairs. More importantly, the issue of priestly crimes still needs to be referred to the religious courts.

This was the famous "Becket Controversy" in medieval history, the result of which the king was eventually forced to bow to the "saint" Beckett, although historians mostly agree with Hume that this "saint" was the "most fearless and stubborn archbishop in history", whose pride and ambition were disguised as the holy and zeal of defending religious rights and interests—a man who had sought fame and glory for the church during his lifetime, perhaps without realizing that "all privileges are unjust, abhorrent, and contrary to the highest purpose of the whole political society." ...... Since the privileged classes enjoy rights distinct from those of the broad masses of citizens, they have in effect broken away from the common law and have become a unique group of people in a great power, a 'state within a state'. Since their aim is not to defend the general interest, but the special interest, their principles and purposes are incompatible with those of the people. ”

It is clear that, because of the supreme glory of Beckett's death, the Clarendon Charter was not enforced, and the privileged clergy were able to enjoy long periods of impunity. As late as the mid-nineteenth century, Thomas Babington Macaulay was puzzled in his History of England (1848): "The usurpation of the power of secular authorities by ecclesiastical groups is a great plague in the present world." Half a century later, In a history of England (1926), Macquarie's nephew, George Macaulay Trevelyan, wrote indignantly of the pernicious effects of the "Beckett Controversy": "Monks and priests, and even various professionals, who have little to do with the church, have committed theft, rape, murder, etc., and as long as they are first-time offenders, they will not be severely punished." It is too easy to obtain low-level teaching positions, and those with inferior character will be attracted to this protection and privilege... Henry II's rash shouts and the recklessness of several knights saved the clergy who had committed felonies for ten generations. The most hated clergy of the Middle Ages, which was most hated by the people, survived for hundreds of years because of Beckett's death, and plagued the people for hundreds of years, which is the fundamental reason why enlightenment thinkers denounced him as a "fake saint.".

To put it another way, Thomas Beckett, the "saint" ordained by the Church, is precisely a historical and national sinner—as George Orwell put it in reflections on Gandhi (1949): "All saints should make a presumption of guilt until they prove their innocence." "------------------------------------------------------

Editor-in-Charge: Huang Xiaofeng

Proofreader: Yijia Xu