Qiao Yu, School of History, Capital Normal University

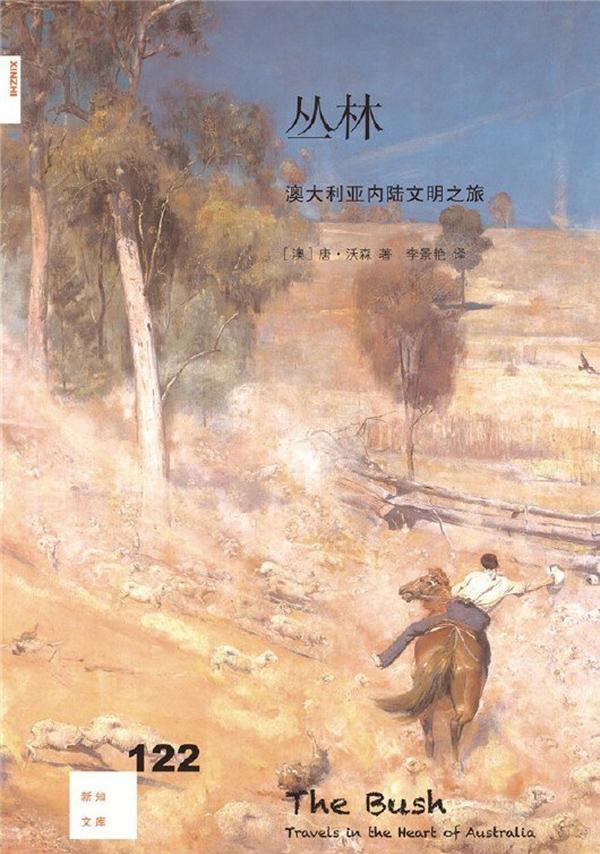

"Jungle: A Journey to Australian Inland Civilization", by Don Watson, translated by Li Jingyan, Life, Reading, and Xinzhi Triptych Bookstore, July 2020, 395 pages, 49.00 yuan

In 2014, Australian author Don Watson, a historian and a writer of the Prime Minister's speeches, published The Jungle: A Journey to Australia's Inland Civilization. The book won the 2015 Australian Independent Bookseller Book Award and the New South Wales Governor's Literary Award. The book has the spatial structure of a travelogue, starting in Gippsland on the southeast coast of Australia, and the author travels westward through the mallee, the Murray-Darling Basin to the wheat belt of Western Australia. This vast area is or was once a jungle strip on Australian soil. At the same time, the book also hides the time clues of the memoir, from the blue wisps of the ancestors, to the sacrifice and glory of the world battlefield, and the struggle of the settlement plan until the drought challenge of the new millennium. The jungle is the starting point for these stories, and the jungle has become an important image in the formation of the Australian nation and the growth of the country. The author challenges the jungle myth and a whole set of jungle narratives that have been formed on Australian soil since the colonial period. Don Watson uses pastoral diaries, oral materials, old photographs and other historical materials, combined with field visits, to reveal to readers what the imagery of the jungle in the historical period was, how the jungle narrative affected Australia's national development, and what kind of jungle concept is more rational and beneficial to Australia's future.

Jungle with jungle mythology

Jungle is first and foremost a changing geographical concept, referring in the Australian context to the Great Dividing Range and its extension, in the broad sense of the inland zone, whose edges continue to shrink westward as the colonization process progresses. Historical bushland areas are the countryside, suburbs, national parks, Aboriginal reserves and deserts of modern Australia. The jungle is also a developing concept of cultural landscape, and in the early colonial period, the jungle meant wilderness, suffering and fear, "unburned land" and "primeval forest" that has not been visited by people (p. 18). The earliest song from the forest tells the thrilling journey of exiled prisoners who escape prison discipline and make a living by robbery in the wilderness. The more widely circulated jungle story is the hymn of the hero represented by Ned Kelly, who robbed the rich and the poor, acted heroically, feared no power, and was the Australian version of Robin Hood. At the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, the group of Australian poets and writers represented by Henry Lawson paid more attention to the jungle, focusing on the jungle with realistic poetry and novels, weaving the story of the jungle into Australia's nationalist narrative and romantic national identity. They faithfully depict the hard life of jungle people seeking to survive in harsh environments. The jungle people are not afraid of hardships, hard work and friendship, so that the wild land into a vibrant agricultural community, the jungle people also from simple, tough coolie to respected landowners. Today, the jungle has become a source of self-awareness and an official worldview for the Australian nation, a unique component of national identity and beliefs. The jungle is the clear smell of eucalyptus trees, the noisy macaw, the small pickup truck transporting livestock, the casual and rugged rancher.

But in the author's view, jungle mythology is a racist male elite narrative from the beginning. From an ecological point of view, the first jungle myth is the jungle itself (p. 73). The word bush is derived from the Dutch word for "boshch". The word originally meant forest, similar to woods in English. In the 1820s, in Australian English, the term was used specifically to refer to uncultivated and uninhabited land in a colony. The settlers of the time also used a number of words that overlapped and were not precise enough to distinguish between different kinds of jungles. Woodlands are called forest, bushes are rush, dense forests are called kick brushes or fastness, the towering rainforests of the New South Wales Colony are big brushes, and vast low eucalyptus forests are called scrubs. Precisely because there was no exact vocabulary in the English-speaking world to describe the landscape they saw, immigrants retreated to choose words beyond its connotation and extension to define what Australia had seen before it was "civilized" by Europeans.

But the jungle was never terra nulius, and aborigines had been living here for tens of thousands of years before the British officially colonized Australia in 1788, and like many indigenous peoples in the New World, many of Australia's indigenous tribes would regularly burn woodland and cultivate and cultivate on this basis. Incineration-type land management adheres to strict rules, the means are convenient and the results are predictable, and reasonable incineration can make forests dense and grasslands open, which is convenient for hunting. Therefore, the jungle is not a "wilderness", but a horticultural undertaking that the indigenous people have been cultivating and maintaining for many years. "Garden" is a term used by colonists to describe the frequency of landscapes they saw, second only to jungle. The exploitation of the jungle is precisely at the expense of the loss of land by the indigenous people. There is a lack of definitive documentation of specific aboriginal population losses in Australian history. It is estimated that after the smallpox epidemic in 1789, there were about 300,000 aborigines in Australia, and about 50,000 to 75,000 aborigines lived in the southeastern pastures of Australia in the 1820s and 1830s. The sharp decline in population has destroyed the socio-economic and cultural foundations of the indigenous people. Not only are aborigines disappearing in the jungle narrative, but aboriginal culture is also lost in the modern jungle heritage preservation cause – the exhibits of the Queensland Town History Museum jump from dinosaur fossils directly to cultural relics from the colonial mining and grazing era. (342 pages)

Ironically, the Europeans of the Victorian colonies at the end of the nineteenth century also began to manage their land by burning, but unlike the natives, they were more accustomed to using fierce fires rather than slow cold fires to advance the burning, and the natives only burned the woodland, and the colonists burned the forest to clear the land. The result was that the Europeans completely changed the landscape of the colony and artificially increased the risk of fire outbreaks. As the edges of the jungle continued to expand to the west and north, european religions ascended and indigenous gods gave way. In "europe where religions are scarce, jungle beliefs take their place". (p. 80) As the nomadic indigenous peoples were forced to settle and entered the cash economy of the colonial era, Europeans became a semi-nomadic people who wielded their whips and lived in the jungles. Colonists also often brought new species to the jungle, with pepper trees from South America, plantagenets from South Africa, and willows from St. Helena. Large areas of forest and woodland eventually struck by invasive plants, and once meadows and gardens turned into impenetrable shrubs from. Of course, what the author does not point out is that indigenous people are not ecological angels, and the recent extinction of large mammals, eucalyptus forests replacing rainforests and other signs show that Australia's jungles are created by effort and effort to grab and grab, and when modern Australians talk about the peaceful coexistence of indigenous peoples and jungles, they also refer to the compromise of these two ecological forces.

Jungle narrative as frontier memory

Jungle mythology deals with the collective memory of the frontier of all Australians, and the author is full of affectionate recollections while looking at it coldly, and his reflection will be reloaded. So it's a work that places a high emphasis on Australian homegrown consciousness, sometimes so much so that it almost resonates with foreign readers. However, even if you are an international tourist with only a solid impression of Australia's blue sea, kangaroo, koala, Great Barrier Reef and so on, when you are in the bustling Melbourne metropolis, the streets are performing digeridoo 's Indigenous entertainers, the aboriginal drunkards on the trains at night, and the crowded Italian streets will remind you that these diluted fragments of history mean that the frontier has only recently retreated from here. Examining jungle memories can give you a better understanding of Australia.

The jungle first records the relationship between people and land on the frontier. From the original squatters, the selecters after the gold rush, the soldier settlers who returned home after the two world wars, the closer settlers, the lumberjacks, the cattle herders, the grain growers, the vineyard growers... After the colonies promulgated the Land Selection Act in the mid-nineteenth century, dozens of occupations existed in the jungle, appeared one after another, then disappeared, and almost never coexisted. This was the way bushmen bargained with nature, constantly probing, fighting or cooperating, and the advance of the frontier eventually laid the pattern of Australia's agricultural geography: land on the southwest, southeast and east coasts of the continent that had grown for more than nine months to produce dairy products, and sugar cane was grown along the northern and Queensland coasts of New South Wales. The southeast coastal highlands are cattle and sheep mixed pastoral areas, and the hilly plains are mixed wheat and wool production areas. The irrigation area is mainly along the Gulburn, Murray and Marambidi rivers. Due to many restrictions such as terrain, soil, rainfall conditions, etc., crop cultivation is usually not continuous. In extreme climatic conditions, much of the reclaimed land is abandoned after cultivation, and farmland becomes jungle again. South Australia has historically drawn a famous "elegant german line", its location basically coincides with the thirty centimeters of rainfall, in the 1870s, in a few rainy years, immigrants poured into the rain line to reclaim farmland to settle, and in just ten years have given up. Beyond the rain line, there are still ruins of the colonial era.

Australia's land selection practices are often compared to inland development after the enactment of the Homestead Act in the United States, and are often considered inferior to the latter. In 70 years, approximately 1.6 million farmers in the United States created 10 percent of America's farmland. Food growers in Australia have also created more than a thousand farms when quality land has been monopolized by ranchers. The barrenness of the soil, the harsh weather, the instability of the market, the proliferation of hares, along with the frustrations of the land-seekers, loneliness and stress, are integrated into the heroic identity of the frontier: bravery and perseverance. (p. 222) Australia is a first-world country heavily dependent on primary industries, and the growth of public and private wealth easily offsets the environmental damage caused by European settlement. This popular frontier agricultural thinking and utilitarian ethic was established in the jungle: it valued short-term vitality and immediate interests, and even ignored the traditional agronomic knowledge of Britain and Europe.

The jungle also creates and revises the social memories of Australians. The first to enter the jungle were ranchers, who occupied the land in a greedy, fanatical way. Then jungle towns formed, where the first colonial political life took place. As the gold rush cooled, the settlement movement in the colonies found alternative ways for miners to work and employment, the middle class in the towns began to seek political exports, and the jungle towns became the center of the democratic movement and the channel of modern communication. Land and power became the focus of the middle class between ranchers and towns: the land question was about who would own the jungle, and the question of power was about who would have the right to rule. At the Melbourne Colonial Council in 1858, these two major questions received an initial response. Rancher-led parliament vetoed bills aimed at correcting land monopolies. The urban middle class is keen on land development, not only because they see the potential of the jungle town proletariat, but also because they gain the possibility of asserting their power in the process of weakening ranchers. On the other hand, the rapidly growing peasants and agricultural workers have also developed at an astonishing rate with the help of the former into a third political force (p. 215). Open up the land to more proletarians, and although they can't share in the initial land and mineral dividends, as long as there is hope to gain a foothold in the jungle, it means that there is hope to enjoy a good life. "A mighty jungle with rails is closely connected to the world." (p. 220) Unlike South America, Australia's land selection bill avoided the monopoly of large estates, and generations of self-sufficient immigrant descendants were born in the arms of the jungle, bringing more towns and communities to the land, becoming a proud model of life for Australians.

The reality of the last hundred years has been that Bushlings have continued to move to the suburbs, with only fifteen per cent of Australians today living outside the urban and coastal peri-urban corridors. The gold rush, the settlement act, the post-war soldier resettlement program, the irrigation settlement program that pushed generations of immigrants and their descendants into the jungle, and then the comforts of modern cities brought them back, this drift lasted for a century, eventually the city expanded, the suburbs spread like the capillaries of the former, and the real countryside almost completely declined: the fallen village towns belonged to the descendants of the jungle people, the vibrant suburbs were home to Middle Eastern and Asian immigrants, and the wilderness and national parks were the last places for the indigenous people. It's also intertwined with Australians' jungle memories of the past. And the jungle towns that nourished the Australian labour movement are becoming the final foothold of conservatism.

The future of the jungle

Jungle narratives also have a direct impact on environmental protection in contemporary Australia. The "wilderness" presupposed by jungle mythology becomes the benchmark for landscape restoration. Nacate in the Murray-Darling Basin in South Australia is a forest that has left an ecological footprint of indigenous and colonialists: indigenous burning remnants, europeans stripping tree bark, salinization caused by reclamation and soil wind erosion are clearly visible. It is also home to many exotic plants, golden chrysanthemums and cang ears that accompany animal husbandry, and African goji berries and redemption grasses are companions of irrigated agriculture. Ninety-two per cent of Australia's virgin forests have been destroyed since the arrival of Europeans. Nonetheless, Nacate has a number of "indicators" to meet the requirements of the South Australian Wilderness Conservation Act. So the state government established a national park here, a million hectares of small eucalyptus forests within the reserve. The South Australian Wilderness Conservation Act requires national parks to restore their pre-colonial landscape, completely remove the traces left by Europeans in eucalyptus areas, and avoid the impact of modern technology, exotic flora and fauna in the protected areas. These goals are undoubtedly unattainable. Nacate represents the embarrassing reality faced by over-idealized concepts of wilderness and rigid standards for Australia's many national parks and reserves.

But the jungle is a moving fragment of natural memory, a landscaped historical material. Scientific and rational modern jungle research will not only help to better carry out the action of soil restoration, but also help modern foresters complete vocational education. The budding Natural Sequence Farming is a constructive concept of reclamation. It not only requires the restoration of the original vegetation and landform as much as possible, but also pays more attention to the function of reconstructing the landscape by imitating the natural evolution system of the Australian landform. For example, the presence of large ponds and swamps in pre-colonial times slowed the flow of water, while the destruction of logging and grazing led to the unrestricted flow of water, damaging soil nutrients, productivity and biodiversity. Restoring pond systems not only beautifies the landscape, but also helps to restore soil fertility and biodiversity, reducing the risk of fire.

This concept of reclamation puts forward higher requirements for the basic research of natural sciences in Australia. The Wallace Line permanently separates the Australian-Guinean species from the Eurasian species. As a result, Australia was geographically isolated, but geologically stable. Species classification in Australia became a huge and daunting undertaking, and until now most of the named flora was done before the publication of On the Origin of Species. Ninety per cent of Eurasian species are known species, which is less than forty per cent in Australia. Evolution is also misinterpreted here, and since the 1820s, naturalists and explorers who have come to Australia have been accustomed to grouping similar plants together, but in fact, as modern genetic analysis has shown, the lineage of plants with similar evolutions may be completely unrelated. So without a reliable classification system, it is impossible to understand the jungle scientifically. At the same time, every day an unknown number of Australian species disappear or retreat into the desert further afield.

By understanding the unknown, we can live more skillfully in the light.

Editor-in-Charge: Yu Shujuan