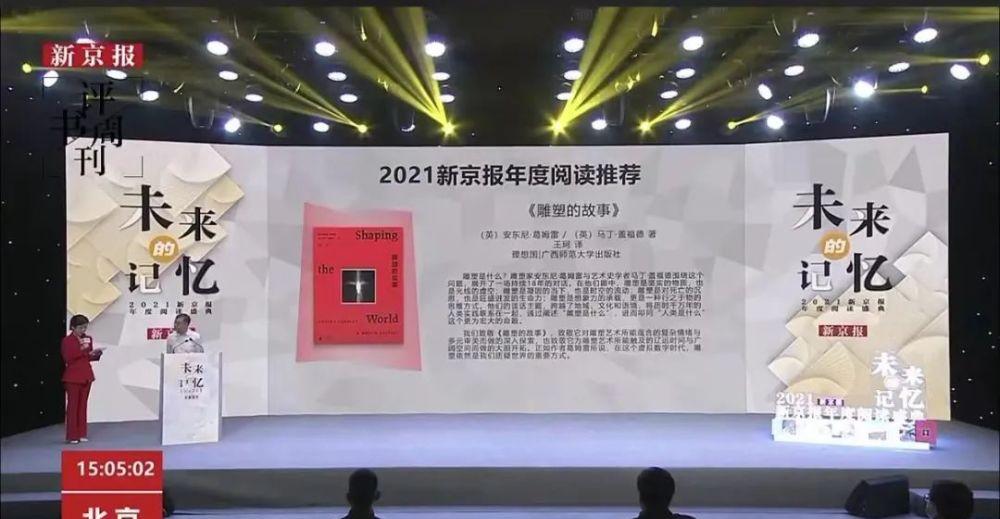

The 2021 Beijing News annual reading recommendation (a total of 12 books) released today, the ideal state has two books on the list - "The Story of Sculpture" and "Cheese and Maggots".

We pay tribute to "The Story of Sculpture", pay tribute to its in-depth exploration of the complex emotions and diverse aesthetics that sculpture art can contain, and also pay tribute to its bold exploration of the long time and vast space that sculpture art can touch. As author Gormley says, sculpture is still an important way for us to question the world in this virtual digital age.

We pay tribute to "Cheese and Maggots", to its profound insights, clean and vivid writing, which gives the boring literature and archives a living life. We would like to pay tribute to the author Carlo Günzburg, who cut through the thorns in the dusty archival jungle and unearthed the extraordinary story of an ordinary person from the microscopic details, and his rigorous, profound and warm historical writing makes us believe that even if it is as small as dust and sand, even if the glimmer of independent thinking will disappear in the long night, it also has the dignity of not being forgotten.

(Excerpt from the 2021 Beijing News Annual Reading Recommendation)

In addition, "Cheese and Maggots" was also selected as one of the top ten good books of the year in the first New Weekly Blade Book Award, Douban annual book, history and culture category, top ten good books read in triptych, private book list of interface culture editorial department, Sohu culture annual good book, searchlight book critic good book list, annual top ten non-fiction translation books, and top ten good books in 2021.

I am really glad that this book has been loved and recognized by everyone, as a masterpiece of micro history, for the first time in the Chinese world, "Cheese and Maggots" has received widespread attention from the beginning of the establishment of the Douban entry, and has received thousands of "want to read" overnight, I believe that readers who have read this book have also felt the "strange, time-space world" described by Carlo Günzburg in the book.

The translator Rui wrote a 10,000-word note at the beginning of the book, and after revising it again, we can finally share this postscript with everyone. For Rui, translating the book was a challenge and a feast.

She wrote: "What every 'liberated' should do is not to give rise to covetous attachments, to label himself as a certain label, or even to take this as a step forward, but to be like them, with joy in life and truth, to constantly make his own voice, and to constantly seek, listen to and transmit those voices that are worth hearing, small and large, or small or small." ”

Tiny Voices: A Translation of Cheese and Maggots

Wen 丨 Rui

One of my favorite passages of the Bible is from 1 Kings chapter 19 of the Old Testament. God appeared to the prophet Elijah, "Before him there was a great wind, and the mountains were crushed and rubble, but the Lord was not in the wind; after the wind there was an earthquake, and the Lord was not among them; after the earthquake there was fire, and the Lord was not in the fire; and after the fire there was a tiny sound." When Elijah heard this, he covered his face with his coat and came out and stood at the mouth of the cave. ”

A few days ago, looking at the book review of "Cheese and Maggots" on Douban, a reader wrote: "This book does write about the divinity of a mortal", which immediately made me feel like a confidant - a year ago, it was the ethereal divinity in the tiny voice of Menocchio, the 16th century miller, who attracted me, who did not feel that I had a "diamond diamond", and then translated the book into Chinese". As Carlo Günzburg repeatedly mentions in the foreword to Cheese and Maggots, many things in the world are purely accidental, including his research and my unexpected encounters with this study.

01

My first reaction was to refuse

Searching for Carlo Günzburg's name on Wikipedia returns a not-so-long but weighty introduction page. You'll see that the Italian historian, born in 1939, became an authority in the field of microhistory at the age of forty with two new classics of historiography, "The Battle of the Night" and "Cheese and Maggots"; his mother Natalie Günzburg and father Leon Günzburg, as well as many of his mentors, have their own terms; he is the winner of the 2010 Balzan Prize, a European prize that is roughly equivalent to the Nobel Prize, which is not well known to the public, in the humanities , the natural sciences and culture are well-known and important...

Carlo Ginzburg (1939–)

But when I first opened this page in June 2020, I didn't really know anything about him and his work.

What prompted the search was a message from Huang Xudong, the editor of the Republic of China. He asked me if I would be interested in translating a book called Cheese and Maggots, "The Enduring Classics of The Great Historian Günzburg." And my first reaction was to refuse.

There are practical reasons for this. At that time, in order to dispel the boredom of the epidemic lockdown and trapped at home, I took several jobs for myself, large and small, and the schedule was already full, including the third book translated for Xudong. However, the two books before this, for various reasons, one ended without illness, and one was delayed, although it did not reach the point of "one drum, then declined, and three exhausted", from a rational point of view, it seems that it is not appropriate to continue to increase the sunk cost. What's more, with my self-taught three-legged cat in Italian, it was enough to read Italian Fairy Tales and Pinocchio with my son, and it was far from translating such an academic work.

But more importantly, there are psychological reasons. Indeed, I have always been interested in history, and I almost transferred to the history department in college. More than twenty years ago, through the recommendation of several students majoring in literature, history and philosophy, I read "Calling the Soul" and "The Death of the Wang Family", which were popular in their circles at that time, but in fact, I was quite slanderous, and I felt that Chen Yinke's "On the Origin of Regeneration" and "Liu Ru is a Biography" were obviously a research path, but the clouds and mist were obedient, and it was difficult to escape the suspicion of foreign monks chanting the scriptures. In the small video room of the school library, I also watched more than once the French version of "The Return of Martin Gale", which was of poor quality and unclear subtitles, but at that time, I also felt that the Hollywood version of "Like the Old Man" starring Richard Jill and Judy Foster, a handsome and beautiful woman, who could understand the English dialogue, was better.

However, taking academics as a career is ultimately a path that I have no choice. What's more, I was originally a lonely person, and in recent years, I have become more and more obstinate after I was born, and I instinctively have a respectful attitude towards "giant qing" and "masterpiece", and I feel that the meeting of the Nine Heavenly Gods and Buddhas is not the turn of my generation of netherworld demons.

Xu Dong did not insist, and the matter came to an end. A few days later, he sent me an electronic version of the English translation on WeChat and asked me to "see."

That night, after cooking, eating, washing dishes, washing clothes, and sending my son to bed, he was finally able to curl up in one of his favorite reading chairs and open the documents on his mobile phone—and when he looked up again, the winter days in the southern hemisphere were getting darker. Over breakfast with his son, he asked, "Were you reading a joke book last night?" I kept hearing you laugh. ”

A few days ago I occasionally saw a quote from the poet W.H. Auden: "Among those whom I like or adore, I find no common features, but among those whom I love, I can find them; they all make me laugh". This immediately reminded me of the night when I couldn't bear to release the volume - is Menocchio, the protagonist of the book "Cheese and Maggots", a cute person who makes people laugh? But that laugh, sometimes it is a smile, sometimes it is a giggle, and sometimes it is a tearful smile.

The next day, I sent a message to Xudong: "I took this job." ”

02

Its story is so moving

The text is so exquisite and perfect

Miao Wei, who recruited me to be a reporter in Sanlian, once gave me a comment that I was interested in everything and dared to write any manuscript: The dog collects eight bubble, and the bubble lick is not clean. But of course people will grow up—in order to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past, the translation process of this book after that, although most of the time can only see stitches and needles, but I have set the rules for myself, no matter what, every day to turn a little. Fortunately, its story is so moving, and the text is so exquisite and perfect, many times, it is like a heart chocolate candy that can dissolve the pain of life and reward daily labor. By the time the manuscript was finally delivered in November, even I couldn't believe that such a thing, which seemed impossible at first, had actually been done.

Most importantly, the moment I clicked to send the email, I had enough confidence to say to myself that this translation was certainly not perfect, but it should be worthy of the painstaking efforts of the writer, the trust of the editor, and the expectations of the readers. This confidence came from the fact that over the course of a few months I became more and more acutely aware that, despite being an untrained layman with no professional training in history, and having failed to live up to the expectations of many of my mentors and friends over the past few decades because of my willfulness, the misguided and accumulated guilt that had become an extremely powerful force in my chance encounter with Cheese and Maggots helped me to reach a wonderful fit with my protagonist, Menocchio, and the writer Carlo Günzburg.

It must be emphasized that this Carlo Günzburg, for me at that time, was not the historical authority who later became famous for this book, but a young Jewish scholar who was on the margins of Italy in the sixties and seventies and knew what loneliness was. At that time, it was only after more than ten years of thinking and entanglement that he chose to go forward on the path of deviant research and further experimented with an unruly academic writing method.

Republic of China produces "Cheese and Maggots" and "Battle at Night"

Yes, although microhistory has gradually become a manifestation in recent decades, any bustling thoroughfare was once a rare road. In His article "Inquisition Judge as an Anthropologist," Günzburg lamented that the archives of the Church of Udine, an important source of literature for The Battle of the Night and The Cheese and maggots, had been introduced to one of his learned Catholics, who was a native friuli and had written several historical works on local heretical events and counter-reformations, but had never thought of the voluminousness of these volumes beneath his eyes. Orderly records of inquisition trials were excavated and used.

This is because, of course, not every road that is rarely taken will become Yangguan Avenue – it may also lead to the valley of no one, or even the valley of death. Take, for example, the records of the inquisitions that once caused the young Günzburg to be intrigued and the envy of many of today's researchers, which were so unnoticed at the time, partly because the protestant historians who first tried to use these documents were mostly conceptually first, concerned only with showing the heroism of their predecessors in the face of persecution, while on the other hand, the wary Catholic historians, It is deliberately or unintentionally aimed at weakening the historical role of the Inquisition, an institution that has become unpopular within Catholics. (See The Inquisitoras Anthropologist as Anthropologist, in Carlo Günzburg's collected essays Myths, Emblems, Clues, (Hutchinson Radius, 1990), p. 156-64.)

So, instead, a young Jewish scholar was given such an opportunity by fate that was not seen as an opportunity in the eyes of the people of the time. In fact, for a long time after the publication of "Night Battle", it was in a "no one's watching" situation, which made Günzburg feel isolated and isolated. (Maria Lucia Paralas-Burke, New Historiography: Confessions and Dialogue, Peking University Press, 2006, p. 236)

1493 Latin edition of the Nuremberg Chronicle

However, obscurity is not the only price to pay for being prejudiced and obstinate. After all, the crime of being convicted of words happened not only to The Miller Menocchio 400 years ago, but also to his close friends in Günzburg.

03

The tiny sounds he heard with his own ears that had been erased, forgotten and distorted

In 1965, the 26-year-old Carlo Günzburg completed his first book, The Night's Battle, relying on the records of the Inquisition trial. Cheese and Maggots was first published in Italian in 1976, when he was 37 years old.

But those who admire Günzburg as a genius today will rarely notice that his father, Leone Ginzburg, an equally multilingual, passionate and insightful intellectual who had emigrated from Ukraine to Italy during World War I, had translated several important works by Gogol and Tolstoy into Italian at the age of 24, and at the age of 24 he and a group of like-minded friends founded the enophony publishing house known for its cutting-edge avant-garde. However, less than two months before his 35th birthday, he died in silence after being tortured in the German-occupied Roman prison, "unable to utter his last words, to say goodbye to anyone, to complete his work, to leave us with even a message" (from a memorial essay by Norberto Bobbio, a childhood friend of Leon Günzburg and italian political philosopher Norberto Bobbio).

Leon Günzburg (1909–1944) and Natalie Günzburg (1916–1991)

At that time, he had only been married to Carlo Günzburg's mother, Natalie Günzburg, a well-off and talented fiction writer, for only 6 years. Previously, although he had been arrested, persecuted and exiled for his participation in the anti-fascist movement, he was full of hope for the future, and he had been making his voice heard and had three children with his wife. Who would have thought that just after the Allies had entered Italy and Mussolini's fascist regime had fallen, the German invasion of September 1943 and the frantic persecution that followed it would leave him alone in the darkness as the dawn of freedom approached.

The popularity of Cheese and Maggots and the 1979 issue of Clues: Roots of anEvidential Paradigm generated a huge response in the global historical community, which certainly made Carlo Günzburg an important figure in Italian culture.

But in correspondence with me, the 82-year-old historian recalled bitterly an impotent experience. In 1991, Adriano Sofri, the leader of the Italian left, a close friend he had met while attending the Higher Normal School in Pisa, was sentenced to 22 years in prison for allegedly instigating an assassination. Günzburg, who firmly believes in the innocence of his friend, has used his historical expertise in studying the trials of the Inquisition to write a book dedicated to this purpose. In Il giudice e lo storico (The Judge and the Historian), he strips away and argues in the hope of convincing the jury of the Court of Appeal that there is no evidence to convict Sophie. However, he failed: the first judgment was upheld, but then Soufri was inexplicably acquitted, but it was not long before the original verdict was confirmed again. Sophie was imprisoned and spent nine years there until he became seriously ill and nearly died before he was sentenced to serving his sentence at home. Ironically, from another point of view, Günzburg was successful. Judges and Historians has so far been translated into 7 languages, and a Russian edition is coming soon.

Judges and Historians in English

All of this reminds us that when we read and talk about microhistory and the small people and small events that are the focus of it, we always ask ourselves when it is really necessary: What is small? What is greater? Where do we come from between the small and the big in the "endless variations between the whiskers"? Where are you at the moment? Where is the future going?

There is no doubt that The change in Menorchio's mindset between trials, presented by Carlo Günzburg in Cheese and Maggots, can help us answer these questions. And an old childhood incident that he has mentioned on many occasions may also help: in the summer of 1944, shortly after his father was persecuted and died, at the age of 5, he and his mother and grandmother took refuge in the mountains near Florence. But because the Germans chose to retreat from there, the planned safe spot became the front line of artillery fire. One day, he was reading a children's book by the Italian children's writer Carola Prosperi called Il più felice bambino del mondo, and his grandmother, the only non-Jew in the entire family, called him over and said, "If anyone asks for your name, you have to say, it's Carlo Tanzi." Tanzi, the surname of his grandfather, one of the oldest aristocratic surnames in Italy.

"I'll never forget that moment," Günzburg said in an email, "and look back, it was at that moment that I became a Jew." I know this sounds a bit contradictory – but the paradox resonates with Jean Paul Sartre's view in Refléxions sur la question juive that the national character of the Jews is the product of persecution. When I read Sartre's article, I thought his views were very unconvincing — but in my own case, I supported them. ”

The protagonist of Cheese and Maggots, The Miller Menocchio

And when I look back at it the same time, whether it is the excitement of the night of the first reading of "Cheese and Maggots", or the tears that filled his eyes countless times during the translation, and the wonderful empathy from many ordinary readers that he read after the publication of the Chinese translation, there is no doubt that it is inseparable from the personal emotions that Günzburg has written into history: the small sounds he heard with his own ears that have been erased, forgotten and distorted, and he himself has become one of the real feelings, and the voice of Menocchio, the 16th-century miller. It has a wonderful resonance that goes straight to the heart.

04

A larger, more wonderful, more fascinating universe

However, it must be pointed out that this review of mine occurred largely after the completion of the Chinese translation of Cheese and Maggots. In the process of translation, despite the many challenges encountered, out of an unsubstantiated doubt that the "dragon slayer boy will eventually become a dragon"—or, more appropriately, my dislike of my habitual "pulling the tiger skin to make a big banner" when I was a journalist—I never tried to contact Carlo Günzburg himself.

It's an adventure, of course, but its inspiration is alluded to the concept of "double-blind experimentation" proposed by Günzburg in his book. Suppose a 16th-century miller, empowered by the Reformation and the printing press, came into contact with a few jumbled books from the point of view of his maggots from the bottom up. (worm's-eye view, an aesthetic term, is usually translated as a worm-to-eye chart or an upward view, a scene that looks up from the ground or the lowest level, as opposed to a top-down bird's-eye view) Looking at it, one can also glimpse a universe that is slightly the same as what ancient philosophers and contemporary humanist elites have seen, so is it possible that a layman like me can also see the sages and draw the scoop according to the gourd?

The possibilities certainly exist, as the risks lie. The first problem is that in the more than four decades since its publication, Cheese and Maggots has been translated into more than twenty languages, and its "translatability" is self-evident. But why, after all these years, has not a Chinese translation appeared?

In addition to the various operational yin and yang differences, a key reason may lie in the particularity of the text itself.

Cover of Cheese and Maggots in Portuguese and Korean

Cheese and Maggots covers different editions in Polish and Spanish

The famous "Cheese and Maggots" is actually a small book, if you skip the preface and annotations, the Italian and English versions are only more than a hundred pages of text, and can be read quickly. It felt a bit like the first time I went to France many years ago to see the Mona Lisa at the Louvre, huddled in front of the crowd and facing a very small painting — the 2,000-piece puzzle of the Mona Lisa that my college friends had sent was a big one. Of course, that smile was charming enough, but I, who knew very little about Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance at the time, was just a hilarity. It was many years before I really began to appreciate it and understand what the masters were praising when they enthusiastically praised the Mona Lisa. In the middle of this, there are things that are not human, joys and sorrows, books that have been read, roads traveled, and decisive leaps of faith.

But the things that helped me understand the Mona Lisa, this time, apparently helped me see a larger, more wonderful, more fascinating universe in the little book Cheese and Maggots. Moreover, Carlo Günzburg is clearly more interested than da Vinci in how his picture of the universe of a 16th-century miller is framed. In several prefaces to the book, Günzburg is like a rather "poisonous tongue" painting critic, pointing at some of the so-called traditional and clumsy lines of painting: "Painting, it is not the only way to draw." And after showing off a stunning sketch, he unveiled his painting kit in the annotation section, unabashedly showing the brush paints and copying, study and scrapped manuscripts he used— "Want to learn?" I teach you! ”

After clarifying the dynamic organic structure of this trinity, the rest of the work is nothing more than seeing tricks and dismantling tricks.

Coincidentally, as a science journalist, one of my professional trainings was to read a large number of academic papers and then rewrite them into text for a general audience in as easy-to-understand language as possible. A few prefaces to the translation of "Cheese and Maggots" just use this old-fashioned style. The translation of the commentary part, apart from that, is most difficult to involve Latin and various European languages. But because of other opportunities, I have been learning Latin and Italian for a while, plus the 800 hours of German for love twenty years ago, and the little bit of fur French I have learned over the years to understand literary films, with the help of dictionaries, academic databases and powerful search engines, the translation process is more of a water mill - of course, unfamiliar is not familiar, eyes, lazy hands, will make mistakes. For example, "La beaute dumort" (the beauty of the dead) in the first edition of the commentary was casually translated by me as "Beauty and the Dead", and as soon as the book came out, it was immediately discovered by serious readers, laughing generously.

For me, the hardest part of the whole process is the text that looks the simplest and the easiest to read. The reason is that as the son of the famous writer Natalie Günzburg, he also had a deep friendship with Italo Calvino, and Carlo Günzberg fully demonstrated his literary skills comparable to that of historiography in this part. The books that the miller Menocchio dabbled in out of a spontaneous passion for reading were extremely voluminous in content, genre, and style, and in the process of interpreting and analyzing them, Günzburg introduced texts with a more diverse content, genre, and style. But with one of his raw flowers, the main text of chapter 62 is tightly structured and natural, the narrative is smooth and the text is catchy—even if my Italian level is limited, it is enough to feel the beauty of the beautiful rhythm of the original text. If it is just a simple literal translation, it will not only fail to live up to the painstaking efforts of the authors, but also fail to reflect the amazing innovation of this historical work when it came out. So I decided to challenge myself to see if I could recreate the book's literary character in Chinese through a layer of English filter.

In this attempt, I reopened many of the books I had read—theological and philosophical works that I had read slowly in recent years to solve the puzzles of life, the social science classics that I had made ad hoc surprises as a journalist for certain topics, and the textbooks I had swept through in college in jurisprudence, the history of Chinese legal system, civil law, criminal procedure, the history of Western legal thought, and Roman law. But the most influential on the appearance of this Chinese translation today is many of the books I myself read haphazardly as a teenager. There are some works and writers that magically echo the inspiration that Günzburg used as a source of inspiration when he wrote Cheese and Maggots, such as "Bible Stories", "Divine Comedy", "Decameron", "Fantasy", "Sherlock Holmes Detective Selection", "Freud Biography", "Oxfly", "Notes in Prison", "Selected Plays of Brecht", "Italian Fairy Tales"... But there are also some seemingly eight-stroke legends, playing words, and commentaries that the book duo has helped me a lot in understanding and translating the 16th-century European popular literature texts that I quote a lot in the book.

05

It's not just these books that matter

And the people who made me meet these books

Yes, I used to be a small town reader like Menocchio. Benefiting from the reading fever and ideological emancipation of the 1980s, as well as the workers, peasants, soldiers, and scholars from all over the world living in a small northeastern city at that time, a girl who had never been a reader in her family also had the opportunity to read the beautiful words poured into the painstaking efforts of countless previous writers, translators and publishers, so as to know the existence of a broader intellectual world, and even set a vision of "seeking something high above" that was not commensurate with her origin. Thanks to the good fortune of the times, this ambition was partially realized more than a decade later, although the famous saying was soon fulfilled: "She was too young to know all the gifts of fate, and had already secretly marked the price." ”

In this process of drawing on previous personal experiences to achieve understanding, it became increasingly clear to me that what was important was not only these books, but also those who had contributed to my encounters with them. Among them, there were primary school Chinese teachers who helped me experience the freedom granted by reading, including the decentralized cadres and intellectuals who gave books to my parents and colleagues when they returned to the city after leaving retirement, the clerks in Xinhua Bookstore and post office who were stern-looking but often secretly helped with a kind of northeast-style wisdom of life, and even my grandmother, who claimed to be "a big character who can't read a basket"—she worked in a printing factory, and often came back with some waste stamps to make fires, paste kang, lay chicken nests, and fold paper boxes. It was through these scrapped sheets that I came into contact with Notre Dame de Paris, the Count of Monte Cristo, and John Christophe in a fragmented and upside-down manner, and forced me to accurately predict the direction of the story with structural layout and foreshadowing.

Of course, I will always be grateful to the young teachers who gave us the new liberal arts students in the suburbs of Beijing as class teachers in the first year of college. In a place where "the temple demons are windy and the water is shallow", they refuse to become accomplices and brainwashing tools of power-grabbers, selflessly open their bookshelves to students, enthusiastically give lectures to us in their spare time, patiently instruct us who were ignorant at that time to read "Tolerance", "The Right of Heresy", "The Myth of Sisyphus" and "The Last 20 Years of Chen Yinke", and sprinkle the good seeds of narrative dissemination and academic research in our hearts.

Among these figures, the one that makes it most difficult for me to forget is Mr. Shen Shuping, who met each other on campus in my sophomore year and guided me to systematically read Western classics for two years. Because of his humility and my youthful madness, it was not until many years later that I discovered that this old gentleman, whose lungs and trachea were not very good, who always told me in a soft and slow voice not to be impetuous and to return to Greece and return to the source of freedom, turned out to be a student of Southwest United University, and the photo of the southwest United University gate that was widely circulated on the Internet was from his hand. After his retirement, he translated The Metaphysical Principles of Law and The Treatise on The Government Films, which helped me overcome my fear of Western philosophers and historians with crooked names, and let me see the simplicity and beauty of the classic originals under the clouds. However, because my mind was distracted and busy with various things that seemed very important at the time, after my junior year, I slowly reduced the frequency of meeting Mr. Shen. Later, through a classmate of the Mountain Eagle Society who lived in the dormitory next to me that Mrs. Shen knew, I went to the school hospital to meet Mr. Shen who was hospitalized for pneumonia, although I did not know it at the time, it was the last side. I clearly remember standing in front of Mr. Shen's bed with a nasal tube inserted, I was very nervous, ashamed, and did not know what kind of storm I would face, but he only asked softly and slowly: "What books have you been reading lately?" ”

Menocchio, the miller in the 2018 film Menocchio the Heretic, suffered a religious trial

For years, I have avoided these memories, consciously or unconsciously, because they all point to a question I do not want to face: How can you do it, and what do you want to repay? But in the process of translating Cheese and Maggots, the voices and smiles of the people I saw with my own eyes overlapped wonderfully with those of Menocchio's contemporaries who loomed in the narrative. Because of the lack of historical materials, Günzberg often only brushsed them over in the book, but when these grass snake gray lines are connected in the translation process, the completion of personal memory and experience allows me to more deeply understand the hypothesis proposed by Günzburg: there is a cyclical relationship between cultures that influence each other, and these influences will flow from the bottom to the top, and will also be transmitted from the top to the bottom.

And in the process, the Word became flesh.

Even if it is flesh, it can never be perfect. But does this imperfection prove in turn that the Tao is not far away, and the seeker must get it?

What made this idea grow stronger were a few things that happened in my personal life at the end of 2020, and Carlo Günzberg's "Foreword to the 2013 Edition" for Cheese and Maggots has led to my growing interest in him as a person. Interestingly enough, the preface to the beginning of this book was translated by me at the end, and the original subconscious was somewhat tainted with fundamentalist pride and prejudice.

But after knowing the whole book well, and looking at the preface, the authoritative Günzburg's sincere reflection on the small and the grand, the narrow and the short, his frank acceptance of the right criticism (in which He mistakenly targeted two letters from Cardinal Santa Severina) and the serious rebuttal of different points of view, as well as his eagerness to "put the golden needle with man", immediately became extremely moving. Blessed are those who believe without seeing it, but for those who have to see with their own eyes and always cannot believe, he does not abuse his authority to despise and spurn, but frankly shows the scars that have been seen and not seen, and teaches people to fish and to fish - there is no need to be condescending, he has his own strength. At this point, I began to regret that I had not tried to contact him for some difficulties and confusions when translating. But since the book had been translated, the necessity seemed to be small, so it was left behind.

Unexpectedly, just when the Chinese translation of "Cheese and Maggots" was about to be printed after the review process, Xudong contacted me again, saying that the Shanghai Review of Books intended to interview Günzburg and asked me if I would like to try it.

This time, I didn't push back.

06

Through them either small or grand sounds

The true divinity that is transmitted

But frankly, it's a huge challenge, and my past as a journalist and as a Chinese translator don't help much. After all, "Cheese and Maggots" has been around for 45 years, translated into more than twenty languages, and all sorts of questions must have been asked by different interviewers in different languages. The first interview outline I had prepared included a dozen modest but general "standard" questions, but just as I was about to read it for the last time before sending it to the editor, I realized with great frustration that most of it could be answered with the words that prompted St. Augustine's conversion: "Pick it up, read it!" ”

So why bother? - "What did you go out into the wilderness to see?" ”

After a night of tossing and turning, I ended up with a series of questions based entirely on my own curiosity, confusion, and reflection, and was actually quite offensive. After Xudong read it, he reminded me with some worries, whether it was too personal, and there were some questions, as long as the old man answered "no" or "no", there was no following.

Naturally, I was worried, but I was as stubborn as ever, insisting on sending a barely modified interview outline to Günzburg, and then saying to myself, even if it doesn't work, what is the loss? A few years ago, I experienced the regurgitation of the right to speak, not to have learned to "pretend to ignore, it is best to observe from the outside" like Menocchio after the first trial, withdraw from the distance, and live my own life. As Confucius said, "I am a little and a lowly person, so I can despise things", fortunately, I was able to live in the prosperous world of Shengping, relying on my own small handle and the kindness of Providence, I could not also warm my clothes and food. What's more, from a journalist to a translator, there is no need to be yoked to say anything, and to be able to make a wedding dress for a lady is simply a pleasure!

But I have a vague hunch that this Italian historian, who looks at the photos and videos on the Internet and has clear eyes that are very similar to Mr. Shen Shuping, may bring me some kind of surprise.

Unexpectedly, this surprise came three hours later, and considering the time difference between the two places, it can be regarded as a second return. Thus began an online conversation that lasted intermittently for more than a month in an intermediary language that was not a native language to both parties.

Two people with vastly different experiences must have set out with their own prejudices and misunderstandings: Günzburg first miscalculated my gender, and then significantly overestimated my interest in and understanding of academic papers in Italian; and I said to myself in shame that even if it was impossible to read the "27 books, 3 compilations, and 171 historical essays" that Mr. Lao had completed by 2019, it should be okay to look at the small part translated into English. It turns out that less than one-fifth of the stacks of books that were gleaned from the libraries of local universities were read with great interest, and it was difficult to sustain them without the special empathy and corresponding historical knowledge of Cheese and Maggots. In the process, I obviously asked a lot of silly questions, but Günzburg always went out of his way to answer them all, and sent all kinds of references depending on my degree. But when I try to sneak around and take shortcuts, he also taunts me just right: "Of course I don't want to steal your precious time." ”

Illustrations in Cheese and Maggots, Part I: A Thousand Worlds, 1552, National Central Library of Rome, Part II: Illustration of the title page of the 1541 edition of The Dream of Caravia, National Library of Austria.

As this fascinating and enlightening dialogue unfolds, I become more and more convinced that with sincere curiosity, prejudice can lead to insight, and misunderstanding may even lead to understanding—in fact, understanding itself should be a cyclical process, a common road, not a fixed end point in Rome.

As an example, when translating Cheese and Maggots, I thought the title was simply taken from a whimsical confession by Menorchio, but after flipping through Gombrich's Art and Illusions and re-reading Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin, inspired by a conversation with Günzburg, I realized that both "maggots" and "cheese" were multi-layered metaphors, with deep radical connotations that I had not understood at the time. After studying Italian and etymology for a while, I realized that even "il formaggio" and "i vermi" were "quadratic metaphors based on metaphors", and that these subtle meanings were inevitably lost in the translation from the Italian version to the English version, and then from the English version to the Chinese version.

This is crucial, of course, but it's not really important. Because in the 82-year-old Günzburg, I clearly saw that "today is" does not necessarily mean "yesterday is not", an inch in, there is a joy to enter an inch. This kind of joy is still great in his old age, far beyond many people who are in their prime but are living in the dead and voluntarily "lying flat".

More importantly, this kind of joy has also been seen in Mr. Shen Shuping's body.

For many years, I have liked the philosopher's metaphor of the finger moon as an ode to the wisdom and courage of the giver, and a warning to the recipient not to analyze the subtleties, nitpick, or even give birth to a little golden delusion on that finger. But in the process of communicating with Günzburg, I slowly discovered that this understanding actually fell into the trap of utilitarianism, which is equivalent to using the heart of calculation to enjoy the joy of the face. Cheese and Maggots certainly begins with a tiny sound, but compared to the book's unusual fame, How can Günzburg's 60-year work be a tiny sound?

Because of the creation of people, Mr. Shen Shuping was only an associate professor when he retired, and he had studied all his life, leaving only a few translations, and due to the limitations of the times, he was not very satisfied with the quality of the translations that year, and began to revise, but unfortunately it was not a day. However, they did not give up going into the wilderness of knowledge again and again, and used every opportunity to extend instructions to those who approached them, and the round shone on the heads of everyone throughout the ages, although occasionally covered by clouds of rain and snow, but with confidence looked up to the bright moon that would eventually be seen. Do they mind if this person is the one they initially chose? Why do they care if anyone inherits their mantle?

Because they have experienced first-hand the beauty of the light, the joy of being illuminated, they believe that as long as they point the way and straighten the path, there will always be latecomers who will follow in their footsteps and extend their fingers at the right time.

This is the true divinity that is transmitted through their small or grand voices. And this joy of theirs is more heart-warming than all the other vanity and vanity that will eventually disappear.

Dürer's "St. Anthony reading" (original cover design of the Chinese translation of Cheese and Maggots)

Remembering this tiny voice, I will wave with gratitude to the miller Menorchio and the historian Carlo Günzburg. The wonderful encounter with them helped me achieve redemption for my past. But what every "liberated person" should do is not to give birth to covetous attachments, to label himself or herself, or even to take this as a step forward, but to be like them, with joy in life and truth, to constantly make his own voice, and to constantly seek, listen to, and transmit those voices that are worth hearing, small and large, or small or small.

For, as Menocchio said, "With the eyes of our flesh we cannot see everything, but with the eyes of the mind we see everything, whether it is a mountain, a wall, or everything..."

Yes, it's a challenge to send out an invitation to each of us, but equally, it's a feast.

Edit the typography Bear Mur

Cheese and Maggots