Author | Cold Research Author Team - Wu Bi

Word count: 5220, Reading time: about 10 minutes

"In the place where the Playboy of Paris flirts every day, a Bashkir man stands in the midst of smoke and fire, wearing a greasy hat with long ear pads, and grilling a steak with an arrow."

- Russian officer Radzechnikov

"A bashkir man in a red robe, a yellow fox-eared hat, and a bow and arrow happened to pass by, causing a burst of laughter in the crowd."

― Russian officer Radozytsky

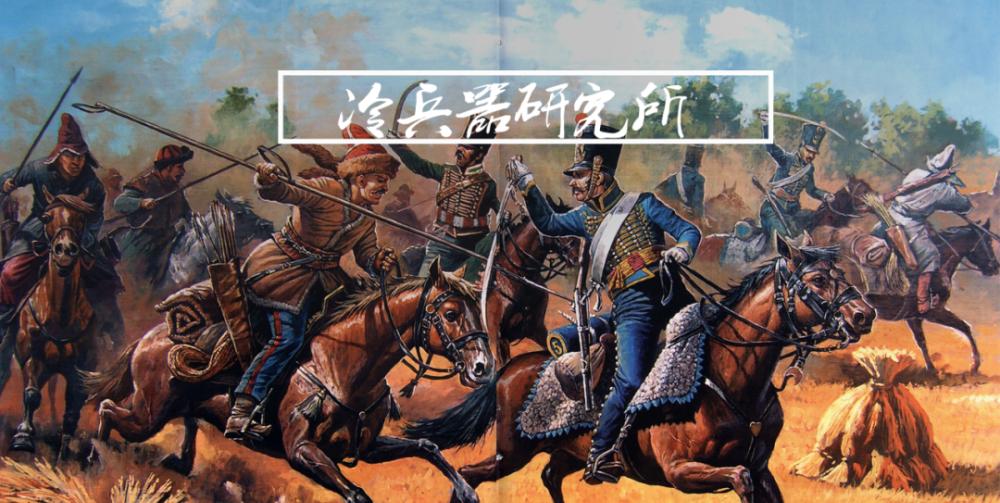

Editor's note: As mentioned in the two sightings above, the European Armageddon of 1812-1814 not only brought the Napoleonic Empire to an end, but also brought the Bashkir herdsmen in the foothills of the Ural Mountains to the city of Paris on the Seine river for the first time as Russian soldiers. So, in this war, in addition to attracting the attention of the people with their strange appearance, what kind of battlefield performance did the Bashkir people show? The Cold Weapons Institute wrote in its previous article, "The Last Use of Bows and Arrows in European Wars: Mongol Cavalry Defeated napoleonic armies in the 19th century by riding and shooting?" It provides a brief description of the armament and combat characteristics of the Russian archers (Bashkirs and Kalmyks) during the Napoleonic Wars, as well as a brief mention of their situation when they first appeared in 1807. This article attempts to analyze and reconstruct the battle of Bashkir's cavalry from both accounts from both sides.

Figure 1. Bashkir in Paris

Figure 2. Bashkir winter hats tend to be equipped with long ear protectors or fox ears

The Imperial Gift was of The Same Cossack origin

As we all know, there are all kinds of chains of contempt within the Russian army, the regular army often despises the discipline of the irregular army, the lawless army also despises the regular army is hierarchical and bureaucratic. Among the large number of irregular cavalrymen, there is also a difference between the early and the late and the alienation of the nation, and the Russian-speaking, Orthodox Cossacks are undoubtedly the most "regularized" and most reassuring group of people in the irregular army, "voluntary annexation" as early as the 16th century (the official Russian term for territorial expansion), and in fact the Bashkir Muslims who adopt the Cossack military district system and the Kalmyks who have converted to Orthodoxy are close behind, to some extent it can be said that they are "of The same Cossack origin". The Kalmyks, who still maintained tibetan Buddhist beliefs, were often seen as the most unreliable group: during the conscription in 1807, the Buddhists even staged a conscription riot, which led to the complete failure of the plan to form two regiments.

Figure 3. Kalmyk icons by the German naturalist Pallas at the end of the 18th century

In April 1811, in anticipation of the possibility of the Russo-French War, Tsar Alexander I ordered the formation of two Bashkir regiments and a Stavropol Kalmyk regiment (the Kalmyks converted to Orthodoxy), requiring that the enlisted soldiers be armed on two horses and "armed according to traditional customs" and customs. At the beginning of June, the three national cavalry regiments were formed, and they immediately embarked on a westward journey. However, although the Russian military leadership generally admired the performance of the Cossacks in the service of light cavalry, there were still many differences in the perception of the national cavalry. The commander of the Second Western Army, Bagrardion, saw these small, oddly armed nomadic cavalrymen of little use and even ordered the Bashkir troops belonging to the legion to be rearmed according to the Cossack model on the eve of the war in 1812.

Figure 4. The Bashkirs rushed to the front

The 1st Bashkir Regiment, assigned to the First Western Army, was much luckier, encountering Platov (Платов), an old acquaintance of the 1807 war, and was able to use his strengths in the first phase of the war. The regiment originally had five hundred troops under its jurisdiction, and at this time, according to the status of personnel and horses, two elite hundred teams were selected for combat, and the rest of the personnel relied on the advantage of the number of horses to drive a "hitchhiker", that is, to use idle horses to carry Russian personnel and materials. The commander of the hunting battalion, Petrov (Петтров), was therefore grateful to Platov's "father", and frankly stated in his memoirs that if it were not for the bashkir ponies carrying backpacks, tools and tired hunters silently carrying their weights, their battalions would have collapsed in the middle of the road!

Figure 5. Platov had a hodgepodge of national cavalry at hand

A duel of light cavalry

French light cavalry expert de Braque once called the Cossacks "real light cavalry" and even the best light cavalry in Europe in "Light Cavalry Outposts". In the War of 1812, Platov's cavalry of various ethnic groups, mainly Don Cossacks, quickly proved with practical actions that de Braque's later summary was accurate.

Figure 6. Mir battle took place

On 9–10 July 1812 (27–28 June 1812), three Polish cavalry brigades (6 lancers regiments) of the French army, in Mir (Мир) in central Belarus, encountered Platov's Cossack rearguard group (11 irregular cavalry regiments and 2 regular cavalry regiments), and after two days of fighting, the Polish lancers with losses of 500 or 600 men were forced to retreat, almost losing one regiment, thus losing morale.

As mentioned above, the 1st Bashkir Regiment did not participate in the battle at the full regimental scale, but sent two hundred troops into battle, and according to the Russian commendation documents, the Bashkir officers Ikhsan Abubakirov and Gilman Hudai Berjin, and the soldiers Uzbek Akmurzin and Blanbay Chuvashev all performed well in the battle of Mir. The Polish general Turno also mentioned the Nomadic cavalry of the Russian army in his bitter and vivid memories:

"We saw only the Cossacks, Bashkirs and Kalmyks on the road, who, with their usual agility, ran everywhere, through the valleys, and then got close to shooting... In an instant, the plains were overwhelmed by lightly armored troops, and I had never heard such a terrible howl... [After encountering the Russian reserves], hordes of Bashkir, Kalmyks, and Cossacks could be seen hovering, encircling, and strangling the [Polish Lancers] squadrons that were stationary in place, and they tried to charge three times, and were repelled three times, while the more cunning Cossacks poured out a large amount of bullets, and when they spent a full four hours running out of anger, the battle was stopped, and the [regular] light cavalry of the Russian army appeared on the battlefield. At the same time, howling nomadic cavalry rounded the woods and charged at our already unfolded left flank, crushing it, sowing terror and death in the 2nd and 11th Lancers... There was terrible chaos in all the units of our army. ”

Figure 7. Mir battle painting by the Polish-Russian painter Mazurovsky

On August 8 of the same year (27 July in the Russian calendar), Platov sought fighter jets in the Molevo Swamp (Молево Болота) and attacked the French 2nd Light Cavalry Division (under the jurisdiction of the 7th, 8th, and 16th Light Cavalry Brigade, a total of 7 cavalry regiments, a total of about 2,300 men, and the 4th Battalion of the 24th Battle Column Infantry Regiment) with about 3,000 cavalry from the 6 Don Cossack Regiments, 1 Crimean Tatar Regiment (1st Regiment), and 1 Dorset Infantry Regiment (1st Regiment).

Figure 8. Schematic diagram of the Battle of the Moljevo Swamp

At 6 o'clock in the morning, the Russian army broke into the French camp, so anxious that the senior generals on the opposite side did not even wear boots, and rushed out to rush out to organize the troops to rush to the battlefield. The French 8th Light Cavalry Brigade, which bore the brunt of the attack, soon fell into a bitter battle, and to make matters worse, Platov, who was marching fast, suddenly drew 2 Cossack regiments and 2 Bashkir Hundred to raid the French flank, and the 8th Brigade immediately collapsed. Lieutenant Жилин) of the Bashkirs, who after the war was awarded the Order of St. Vladimir of the Fourth Class, was awarded the order of Bashkir, whose medal indicates that bashkir cavalry first threw themselves into scattered warfare, engaged in confrontation with the enemy (it seems that Platov had not forgotten how he used bashkirs in the last war), and then rushed into the enemy position with the Cossack regiment to crush them, in addition to 6 Bashkir officers and men "set an example for others, showed extraordinary bravery, defeated the enemy cavalry, and pursued them until the reinforcements", As a result, he was promoted.

Figure 9. Don Cossack - Ataman Pratov

At about 8 o'clock, the French 7th Light Cavalry Brigade began to line up to meet the Russians, but this kind of oil-filling style of rushing to deliver vegetables was very much in line with Platov's appetite. Captain Maurice de Tascher, Queen Josephine's distant cousin, witnessed another rout:

"We were outnumbered, retreating in an echelon in disorder, and the chaos led to obstacles in the road. My mount was also killed... There were also Kalmyks and Bashkirs with bows and arrows! ”

The last group of the 16th Hussar Brigade to meet the battle was a foreign force in the French Army, consisting of the 3rd Hunting Cavalry Regiment in Württemberg, the 10th Polish Hussar Regiment, and the Prussian Mixed Lancers Regiment. The Germans and Poles generally maintained their horses higher than the French, and the preparation time for the day was relatively long, so they only retreated in an orderly manner in front of the Cossacks, and there was no sign of collapse. Roos, a Württemberg medic, later recalled that he had witnessed the bow and arrow for the first time in the battle: a Polish hussar officer had been shot in the right flap of his ass by it, and a fellow hunter had been shot through his clothes by an arrow.

Figure 10. Bashkir cavalry pursued the French in the Battle of the Molevo Swamp

Since then, the Bashkirs have participated in almost every light cavalry outpost and rearguard battle of the Russian army. Lieutenant Radozhsky of the 3rd Light Artillery Company of the Russian Army recalled:

"We especially enjoyed watching the various tricks and tricks of the Bashkirs, wearing ear hats, shooting arrows like cupids, buzzing around the French hunters, charging, retreating, luring them into ambush sites, then gathering again, screaming and attacking, and then dispersing again."

Lieutenant Combe of the 8th Hunting Cavalry Regiment of the French Army also pointed out that the Cossacks, Bashkirs, and Kalmyks formed a thick scattered line to cover the retreat of the main Russian army, which caused some of the hunters to be wounded by bows and arrows, but the hunters also killed some "very ugly" Bashkirs in the scattered battle.

Zimmermann, the lancer of the 9th Lancers, described the Russian nomadic cavalry as "a bunch of rampaging devils" in his memoirs, saying that they had yellow-brown skin, wore narrow coats, pointed headdresses, and rode back and forth on ponies, believing that these people could wield weapons skillfully and whose cries were extremely terrifying.

Figure 11. "Rampage of the Devil"

There is no need to enumerate too many records of both sides here, in short, the Bashkir people were indeed able to perform well in the light cavalry battle in 1812, but often lacked room to play in the battle of the column, taking the Battle of Borodino as an example, the 1st Bashkir Regiment had a good performance in the pre-war and post-war rearguard battles, but on the day of the battle, it was idle.

The Vietnam War became stronger

However, oral history collected later mentions a confrontation between bashkir nomadic cavalry and French heavy cavalry (probably cuirassiers). Bashkir veteran Janchoria (Джантюря) once recounted that he and about 50 of his comrades encountered 20 French cavalry "with steel badges" on patrol. The Bashkirs saw this as a good opportunity to fight more and fight less, so they jumped on their horses and charged over with their rifles. With the speed of his mount, Zhan qiuria immediately pierced a French war horse, but just as he was about to pull out his mounted gun, another French cavalryman slashed at him with a sword, and Zhan Qiuria was not killed on the spot in chainmail, but he was also unconscious. When he woke up as a prisoner, he found that only 12 of the 20 French cavalry had been left, but 50 of Bashkir's comrades were completely annihilated: half killed and half captured.

Figure 12. A scene of a showdown between the Bashkirs and the cuirassiers by modern Bashkir painters

This story illustrates the great disadvantage of the Bashkir light lancers, who used bows and arrows as a secondary weapon, in a head-on duel with heavy cavalry. Of course, the ending of the story is still a comedy for Jantyria: as soon as the battle began, his wife, who was on the army, ran out in search of the main Cossack force, and an hour and a half later, a Cossack Hundred suddenly appeared and solved the remaining French cavalry...

Figure 13. Modern Bashkir painters painted Bashkir female warriors based on the story of Jantyuria, mixed with imagination

However, for "old qualified" units such as the 1st Bashkir Regiment, with the russian counter-offensive and the retreat of the French army, officers and soldiers began to find ways to collect and use various types of captured equipment, not only becoming more and more adapted to the battlefield of the hot weapon era filled with gun smoke, but also gradually developing in the direction of firearms. On April 2, 1813 (March 21 in the Russian calendar), the regiment participated in the Russian-Prussian army's surprise attack on the French army near Lüneburg, and in the battle, contrary to the traditional perception of nomadic cavalry at that time, it braved artillery fire to raise its mounted gun and take the lead in breaking into the infantry and cavalry covering the French artillery. On December 19 of the same year (December 7 in the Russian calendar), the regiment and a squadron of hussars raided the Terheijden ferry in the Netherlands with 2 guns, capturing 200 French troops who had come to seize the crossing.

Figure 14. Expedition to the Bashkirs (close-up) and Cossacks (far-range) to the Netherlands in Western Europe

The role of armed firearms in the Battle of the Bashkirs also increased, also in the case of the 1st Regiment, which consumed 2,000 rounds of long guns (rifles, carbines) and 1,270 rounds of short guns (pistols) during the scattered war near Leipzig on October 7-8, 1813 alone.

In short, like other Russian irregular cavalry of this period, the Bashkirs studied warfare in warfare, and their weapons gradually moved closer to the common standards of European light cavalry: mounted guns, sabre, carbines, pistols.

Figure 15. The church spire in Schwarzsa still retains a replica of bashkir's arrow

At the same time, the Bashkirs are still proud of their ancestors' bow and arrow skills. On April 26, 1814 (April 14 in the Russian calendar), on its way back to China, a Bashkir force passed schwarza in the Thuringian region, showing off their bow and arrow skills to the Germans, but someone was in trouble online, claiming to test the power of the bow and arrow on the spot. After some back-and-forth translation, the nosy priest simply asked them to take a test shot at the church spire a hundred meters away. So, a Bashkir archer Ma Liding shot an arrow through the square, cleanly hitting the spire!

Resources:

de Brack, A.-F., Light Cavalry Outposts. Paris, 1831.

Turno, C., Souvenirs d'un officier polonaise générale Charles Turno (1811-1814) // Revue des études napoléoniennes, 1931, t. 33, p. 99-145.

Popov, A., An Expedition to Lüneburg, ler-3 April 1813 // Tradition, 2013, No255, p. 20-30.

Popov, A., Regards sur les troupes irrégulières russes // Tradition, 2013, No267, p. 19-28.

Benkendorf, A. H., Benckendorff's Notes. The year is 1812. Patriotic War. The year is 1813. Liberation of the Netherlands. M., 2001.

Petrov, M. M., Stories of Colonel Mikhail Petrov, who served in the 1st Jäger Regiment, about the military service and life of his and three of his brothers, which began in 1789. 1845 The year is 1812. Memories of soldiers of the Russian army. M., 1991, S. 112-329.

Radozhitsky I. T. Pokhodnye zapiski arkillerista, s 1812 to 1816 goda. M., 1835.

Rakhimov, R. N., Evolution of the armament of the Bashkir cavalry in the era of the Napoleonic Wars // War and Arms: New Research and Materials. Proceedings of the Third International Scientific and Practical Conference 16-18 May 2012, St. Petersburg, 2012. Ch. III.C. 98-108.

This article is the original manuscript of the Cold Weapons Research Institute, the editor-in-chief of the original outline, the author Wu Bi, any media or public account without written authorization shall not be reproduced, violators will be investigated for legal responsibility. Some of the image sources are online, if you have copyright questions, please contact us.