We are familiar with the "interstitial welcome", which often means courtesy and respect, but in european armies, for thousands of years, another terrible interstitial passage was practiced - "running the gauntlet".

The "torture of the middle road" has a very long history in western armies, and it has existed since ancient Greco-Roman times. The Greeks called it xylokopia and the Romans called it fustis, which was roughly an open staffing or whipping. However, unlike ordinary flogging and cane punishment, it is personally executed by the prisoner's military comrades left and right, which is not only a physical punishment, but also a spiritual humiliation, which is quite cruel. Roman legions sometimes even used it to enforce the infamous decimatio (a collective execution by lottery of one-tenth of rebels, fleeing battles, and losing their flags).

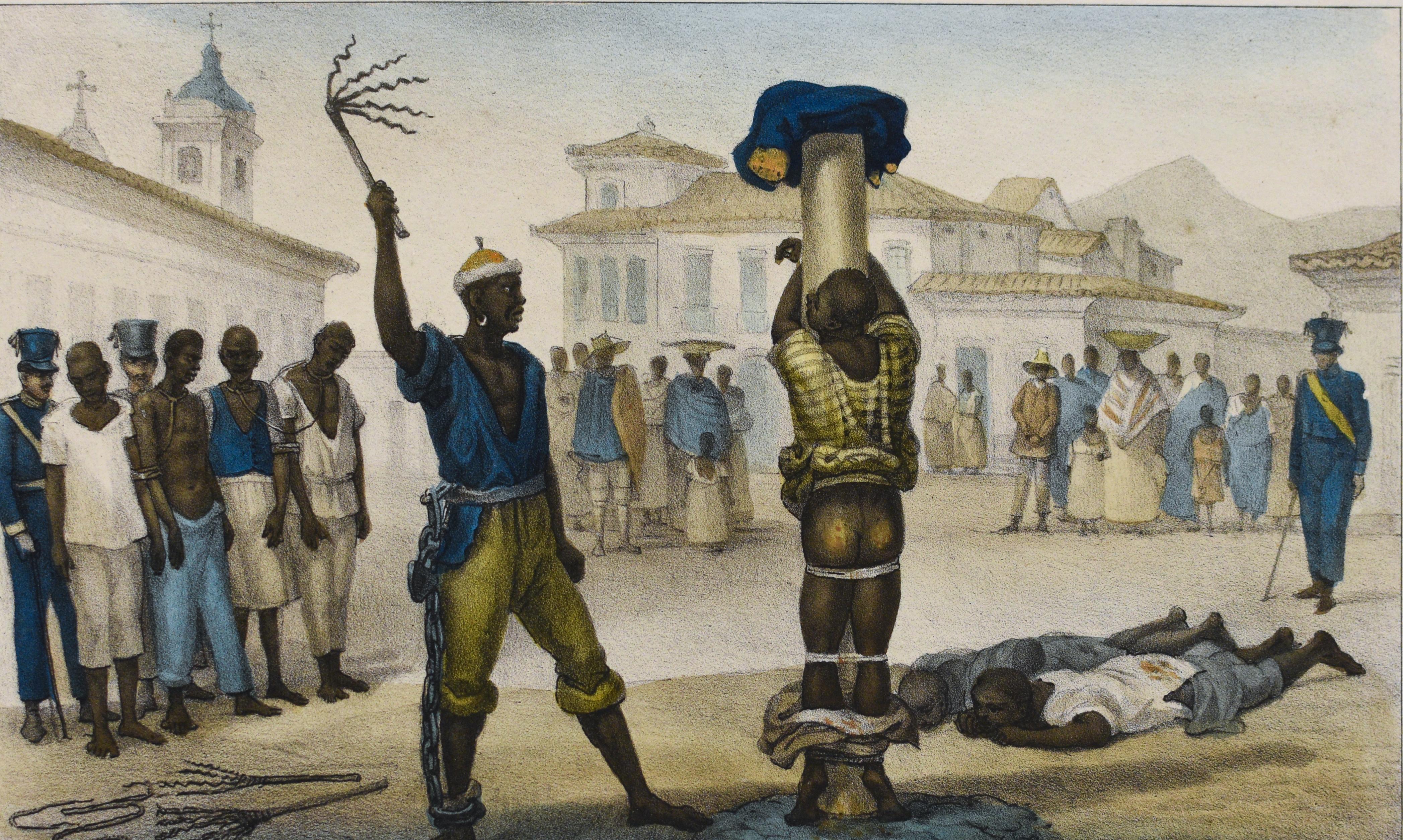

Ordinary public flogging, painted by the French painter Jean Baptiste Debray (1768–1848).

Eleven killings in the Roman army

Modern European armies have inherited this special punishment and have even "introduced new things". The term "running the gauntlet" that is common in the English-speaking world today sometimes confuses Chinese readers because it literally means "running metal handguard." In fact, this theory was introduced around the time of the 30 years of war in the 17th century, when the British army fought side by side with the Swedish army. The source is the Swedish word gatlopp (a combination of road and running), originally transliterated in English as gantelope, and later became a more generic running the gauntlet because of its resemblance to the familiar term gauntlet (the handguard part of European armor) as a result of false rumors.

The gauntlet of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I is not directly related to the "torture of the middle road" in military law.

The "torture of the middle lane" in modern European armies has usually been carried out in the following way: the punished soldier is stripped of his shirt and his comrades are "welcomed" with sticks or whips. The executioner walked in front of the prisoner with a sword in case he escaped. Occasionally, they would be tied up, and the executioner would drag the rope in his hand like an animal. According to the most demanding tradition, prisoners must persist in completing the ranks in order to successfully atone for their sins. At this moment, he has won his innocence and can return to the army. If he gives up halfway, he has to start all over again, and the cycle repeats until he dies. In some of the more humane rules that have been modified, if the prisoner is really physically exhausted and unable to continue, the executioner will announce the termination and the prisoner will be able to retrieve a life.

The "Torture of the Middle Passage" recorded in the 1564 print

This particular punishment is not without rules. For example, soldiers who are beaten on both sides are often required to use blunt instruments such as sticks, while open-edged weapons are prohibited so as not to leave fatal wounds. While on the march, prisoners were allowed to protect their heads with their hands— so that the main part of the blow was on the back— and the executioners were required to keep at least one foot on the ground, thus eliminating malicious, desperate beatings. All in all, although there is no lack of physical destruction, the main intention is to punish and insult the spiritual level, not to take people's lives, which is somewhat similar to the shackles that were once popular in Europe. Of course, the execution of the middle lane is shorter and more private than that of ordinary shackles (usually only within the barracks rather than in public), but the fear, pressure, and risk of prisoners facing long rows of executioners are not comparable to those of shackles.

European shackles in the 17th century

By today's standards, the punishment is cruel. However, many officers regard it as a means of "curing the sick and saving people", and what is even more paradoxical is that because this punishment must rely on many soldiers to execute, it can instead embody a certain grass-roots "democracy" and even objectively correct the punishment of the superiors. In 1760, for example, an English sailor named Francis was punished three times by an officer for returning to the fleet for a little late report—a fatality if enforced strictly. His comrades complained and felt that they were too harsh, but the officers refused to take back the order. Thus came a spectacle in which all the executing sailors were "lifted high and gently lowered", and Francis was tortured three times, and finally he was almost unharmed.

For all these reasons, the "torture of the middle way" has existed in Europe for a long time. After the French Revolution of 1789, the revolutionary government abolished the "torture of the middle lane" in the French Army, but the navy continued to retain it (the navy of that era was more prone to mutiny and the number of soldiers was not easy to replenish). The same punishment (spießrutenlaufen in German) is also prevalent in German-speaking countries such as Prussia and Austria. The Prussian cavalry even had its own unique "invention" – replacing the general wooden stick whip with stirrup rope. The relatively civilized British Royal Navy of that era also carried out this cold punishment for a long time, and it was not abolished until 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars. The more closed and backward Russia was implemented until the mid-to-late 19th century, even in Tolstoy's novels.

Russian troops executing the torture of the middle road in 1845

After the 19th century, the management of Western armies became increasingly institutionalized, scientific, and humane, and outdated and ugly punishments such as flogging, "torture in the middle of the road", and "cale" (the prisoner was tied to a truss and repeatedly immersed in the water with his head down) slowly withdrew from the stage of history, of course, the punishment for desertion, mutiny, and non-compliance with military orders was equally strict. Some foreign military academies still retain a special "torture of the middle road", but this is only to train the courage of the trainees, not to be a kind of corporal punishment, let alone fatal. Today, we can only rediscover this punishment in works of art — for example, the American literary hero Hemingway's "For Whom the Death Knell Tolls" and the great director Stanley Kubrick's 1975 film Barry Linden.

Poster of Barry Linden