Xiao Gongquan Don't eat me

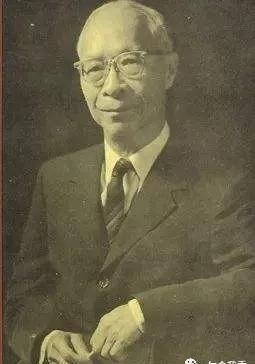

Author| Xiao Gongquan (1897--1981)

Famous historian and political scientist, the first academician of academia sinica, successively or concurrently served as a professor of Yanjing, Tsinghua, Guanghua, Huaxi and other famous universities. He left Taiwan in 1949 for the United States and was a visiting professor at the University of Washington Institute of Far Eastern and Soviet Studies, retiring in 1968.

Although the environment of the Qing Empire was different, regardless of the rural life, the gentleman (who held the title of official or scholarly title) seemed to be the most positive factor. There is some indication that the gentlemen of the rural south of China are more active and more influential than those in the north. Although the author does not have enough information to prove this conclusion, it is reasonable to speculate that in the villages where there are more gentlemen, the economic environment is better; the more celebrities, which in turn promotes the prosperity of the villages. In small and poor villages, gentlemen do not have much room for activity, even if the gentry with special status really choose to live here. In such villages, the gentlemen have become almost as devoid of vitality as the ordinary inhabitants of the village, essentially abandoning the duties which their companions in the prosperous village are performing. The scholars of a certain place in northern China struggled in the harsh economic environment in which they lived, and almost completely lost the enterprising spirit possessed by the elite group. According to a local chronicler:

...... The scholar is still simple, or pro-hoe, and at first there is no control of the township, and the current politicians are discussed. However, the old custom is that after the children win the green shirt, they do not seek progress.

Knowing this, the next step is to explore the role of the gentleman in the countryside.

The development of a village depends to a great extent on the leadership provided by the gentry—retired officials and titled men—for limited organization and activity. People who have been trained by the imperial examination and have a special social status actively promote community activities, including the construction of irrigation and flood control projects, road construction, bridge construction, ferrying, settlement of local disputes, creation of local defense organizations, etc. It is no exaggeration to say that the gentleman is the cornerstone of the village organization. Without gentlemen, the countryside can survive, but it is difficult to have any well-organized village life and decent organizational activities. As long as the gentry intends to maintain order and prosperity in their communes, their leadership and activities will bring widespread well-being to their neighbours. In fact, they seek to protect local interests against all kinds of government abuses— such as extortion or corruption by state and county officials and their pawns. Their knowledge and special status often empower them to resist openly and even to make their grievances compensated.

However, it would be wrong to infer from the above situation that the gentleman' relationship with the Qing government as a group was hostile. Instead, retired officials and scholars with titles or ambitions often maintained the rule of the Qing dynasty. As scholars, they generally had to prepare for or take competitive imperial examinations; as a result, their attitudes and positions were influenced to varying degrees by King Kongo Confucianism. In general, they were loyal to the emperor; even though they had no official positions or political duties. After the officials temporarily or permanently retired and returned to their hometowns, they had no intention of opposing the Qing government or challenging the imperial court. Although intellectuals do not have the status of officials, they are future officials; or, in the words of a 19th-century Western scholar, "they are people with expectations." Unless a scholar's expectations are completely disappointed, he generally prefers to maintain the existing regime rather than political turmoil. Even those who possess the status of gentlemen have the sole aim of "protecting their families and neighbours from the encroachment of authoritarian power", and this is achieved on the condition that the regime granted to them is universally recognized by the people. Therefore, they are also inclined to maintain the existing regime.

Therefore, under normal circumstances, gentlemen play a role in stabilizing rural society. The emperors of the Qing Dynasty had good reasons to use the gentry to rule the countryside; in fact, they tried to control the gentry to a certain extent in order to achieve the goal of controlling the countryside.

Unfortunately for the Qing rulers, however, normalcy did not always exist. Sometimes, the gentleman plays a role of destruction rather than stability. Those in privileged positions were often blinded by their own short-sightedness and selfishness, and what they did (perhaps unconsciously) endangered not only the interests of their neighbors, but also the interests of the qing rulers. Since earlier, the squires have been notorious for exploiting and oppressing ordinary villagers. When a historian of the 18th century mentioned the situation in the Ming Dynasty, he said, "The gentry who live in the countryside also rely on the powerful and bully, and regard the small people as weak meat." As it turned out, this situation continued in the Qing Dynasty, and in 1682 the Kangxi Emperor found it necessary to send some high-ranking officials as Chincha ministers to inspect the situation of haoqiang and abuse of the people. The Qianlong Emperor issued an edict in 1747, which had the following words:

In the past, the squires everywhere were arrogant and arbitrary, abused Sangzi, bullied and insulted the neighbors, and greatly harmed the locality. During the Yongzheng period, the rules were strictly enforced, and the gentlemen knew how to abide by the law. ...... It is the recurrence of old habits in recent days, and there are people who have disregarded the merits and orders and acted arbitrarily. Provinces may not be without this, and Fujian Province is particularly important.

Although the Qing Dynasty issued a series of prohibitions and adopted some punitive measures, some gentlemen still oppressed the villagers. Although some particularly bad or unlucky gentlemen were punished by "grafting", the vast majority of gentlemen still enjoyed a dominant position, and could still use this position to exploit and sacrifice the interests of ordinary villagers for their own profit. As we have seen earlier, gentlemen, as taxpayers, enjoyed the special favors given by the Qing Dynasty, often using their position to pass on some of the obligations that they had originally undertaken. Those in privileged positions often resort to force or deception for material gain; this in turn further strengthens their power and makes them more greedy. In the presence of very powerful gentlemen, even the less powerful gentlemen were not always able to protect themselves; ordinary villagers were often completely slaughtered by them.

Some of the exploitation and oppression adopted by the gentry have been pointed out earlier, but some examples can be added to illustrate the role of the gentry in the countryside. In some cantons and counties in Guangdong, large households regularly send thugs, armed with weapons, to harvest by force the crops that villagers grow on sand fields; this method is called "chamsha". In Shanxi, both Xiangling and Linfen rely on the waters of the Pingshui River for irrigation. The big households arbitrarily decide on "water conservancy"; ordinary farmers will not get water if they do not buy "water coupons" from them. This unfair situation persisted, and finally a strong revolt broke out, which attracted the attention of the Qing government in 1851. In Taixing County, Jiangsu Province, a famous martial artist heard that a villager had stored some silver, he falsely accused him of selling illegal salt and robbing him of all his property. The villain with the title was not punished until 1897. Sometimes, the squire made the rules themselves. In some prefectures and counties in Jiangxi, "big households" have privately formulated prohibition rules for villages and towns:

Poor people who commit crimes do not call officials, or wrap themselves in bamboo baskets, sink them in water, or dig earth pits, bury them alive to death, strangle relatives, write standing clothes, and are not allowed to make a sound.

As we pointed out in our discussion of village regimental training, the powerful use local defense affairs to get their hands on it. In the 1860s, the Governor of Liangguang summarized the popularity of Liangguang:

His unwise gentry, by virtue of profiteering and bribery... Even the small people, the chief, the martial students, the wen tong... Blackmail the crowd to order Yiyi. ...... The great gentleman is quoted as a minion, and the long official is false.

Shameless gentlemen will not hesitate to resort to deception and extortion for the purpose of obtaining illegal income or protecting vested interests. The example of illegal income can be found in Xiangshan County, Guangdong Province. According to the Xiangshan Chronicle, the peasants (including sharecroppers and self-employed farmers) organized themselves to protect their land and crops against looters. Their self-preservation organization has been in existence since the last 25 years of the 17th century. By the 19th century, however, two senior officials in Shunde who had retired from their posts and returned home were authorized by the Qing government to organize regimental exercises. Using this as an excuse, they incorporated self-defense organizations in the villages of Xiangshan County into a wide-ranging organization and then demanded more and more donations from farmers. The final amount collected amounted to 200,000 taels of silver, while the actual total cost was less than 80,000 taels. The two former officials never provided any balance lists.

The example of the use of deceptive extortion to protect vested interests can be found in Dongguan County, Guangdong Province. In 1889, a dispute broke out between the local magistrate and some gentlemen over the rent of the official land. The gentlemen convened a "council of the whole estate" to discuss measures against magistrates. Among these local leaders was a jinshi, a lifter, and a probationary who had donated a sanpin official title. Under their leadership, the council decided to petition the prefect for his due sympathy for "public property". Obviously, at their instigation, the "soldiers and people" of the whole county jointly signed a notice of support for them. The prefect replied:

The county's soldiers and people labeled a long red cloud: "Hexian righteous deeds, look up to Yusi." ”...... Honbudo knew that the long red marked by the people of the Yi shimin was posted by the gentleman, but with this as a word, if the county instructed the manager, then Yun: "Where the anger of the people lies, do not dare to operate." "To delay it.

The prefect may not have been very impartial, but as further developments have shown, his allegations are not necessarily entirely unfounded.

Although not all gentlemen are selfish or oppressive, the stabilizing role of the "just gentleman" is offset by the actions of the "inferior gentleman". The oppressive rural elite has become a destructive force in their village communities; in the long run, its destructiveness is not only to undermine the "social relations of solidarity" that may exist in them, but also to undermine the economic balance of Rural China. They are self-serving and rarely contribute their energy and financial resources to the development of their villages. Many of them "celebrities" choose to live in towns or cities, especially after attaining considerable wealth and status. There, they feel more secure, more prestigious, and more extensive. They allowed their homeland to struggle or decay in harsh conditions.

In this case, the gentry were not only no longer the auxiliary forces that the Qing government could use to rule the countryside, but in times of social unrest, they were more likely to cause dissatisfaction and revolt among the peasants; even if they did not openly or directly clash with local officials, they also hindered the Qing Dynasty from fulfilling its expectations of maintaining the order of rural rule. When they became de facto de facto demagogues (secretly joining the "thieves" or actively launching a popular uprising), they posed a direct threat to the Qing dynasty's rule itself.

The evidence shows that imperial control was never so thorough and complete that local organization could not be made possible, local autonomy unnecessary, or complete obedience by the rural population. Villages, where both size and prosperity have reached a certain level, show the state of village community life; in different environments, the purpose of various village community activities is mainly to protect local interests. As long as these activities served the general interests of the villagers, they played a role in the stability of rural life and thus indirectly benefited the rule of the Qing Dynasty; this situation partly explained the fact why, until quite recently, the Qing government had not encountered any serious difficulties in maintaining control over the vast countryside, even if its various grass-roots control mechanisms were not fully satisfactory.

Although the Qing government generally did not interfere in rural organizations and activities, rural China did not enjoy true autonomy or exhibited genuinely democratic social characteristics. Although many villages have an organized presence, not all villages have established organizations; even in the villages where there are organizations, the scope of public activities is not only limited, but there are almost no mass activities carried out by all villagers on an equal basis. It is extremely difficult to find an example of a village-wide organization working together for the benefit of all villagers. Most organizations are formed only for a special purpose, but only to meet temporary needs. Their members usually include only a subset of the villagers. Although ordinary villagers could participate in village affairs and even act as leaders, they were often controlled by the gentry. The gentleman largely determines the form and direction of the organization of rural life.

Due to the limitations of the actual environment, the control system implemented by the Qing Dynasty over the countryside was incomplete and could not be complete. To a certain extent, the Qing government purposefully allowed the villages and villagers a certain degree of freedom, so that they could use certain attitudes and organizations of the villagers to serve their rule. However, because this system of rule was incomplete, it was impossible to guarantee that the rule of the Qing Dynasty would be maintained for a long time, and it left as much room for attitudes and activities that endangered security as those that were conducive to security. This system allows for social stratification and divergent interests; according to the principle of "divide and rule", this may be exploitable, but it also hinders the development of the countryside into a solid community, making it incapable of solving the problems of real life in a sinister material environment. Under normal circumstances, the stability of China's rural areas does not depend on the subjective will of the villagers to maintain stability, but on the existence of destructive forces.

The population of rural China is not homogeneous, but we need not stress this too much. Socially, the inhabitants of a village are usually divided into two main groups, the "gentry" and the "people"; economically, they can be divided into rich landlords and poor sharecroppers, and this line, although variable, is clear. Although the legal status of the gentleman is not based on wealth (land or otherwise), social status and wealth are closely related because the gentleman has more access to wealth than the common people; this is one of the reasons why the organization of Chinese villages is rarely comprehensive, and the cooperation between villagers is often limited. Although the Marxist view of the "class struggle" between the two large rural groups is far-fetched, it seems clear that there is no such thing as "common social relations" between them. At every level, its interests and purposes are different, and the resulting "conflict of relations" prevents the village from developing into an autonomous unit, one that is effectively prepared to deal with adverse circumstances. No matter what kind of serious crisis, it can put the rural masses in a state of utter despair. In the face of an emergency, the villagers did not unify their thinking, actions, and joint efforts to solve the problem, but acted independently; many villagers were forced by the situation to change their habitual positions and behaviors. The already unstable political and economic balance can easily be undermined. In this case, at best, the system of rural control, which can be called incomplete, is severely damaged and has little effect.

However, there are some special cases worth mentioning. In some parts of the Qing Empire, especially in southern China, clan organizations often coalesced villages into a unit that was closer together than in other regions. The existence of clans made the form of rural organizations slightly different, and brought a series of different problems to the rulers of the Qing Dynasty.

—end—

This article is an excerpt from The Chinese Countryside: Imperial Control in the 19th Century, with notes omitted