Author 丨 Cui Xueqin

The skull and middle ear of the rhinoceros

Retrieval of the Toothed Beast

On January 28, Nature magazine published online the cooperation results of the Inner Mongolia Museum of Natural History and Yunnan University. Based on the new discovery of the connection between the auditory ossicles in the middle ear of mammals, this study proposes that the overlapping anvil-hammer joint is a key step in the separation of the middle ear ossicles from the jaw, and solves the long-standing problems in the study of the evolution of the middle ear and hearing in mammals.

"The study, which spans three years, synthesizes evidence of fossil and emerging ontogenesis and contributes to a clearer understanding of the evolution of mammalian unique auditory organs." The evolution of the mammalian middle ear involves complex details and is the best example of the extended adaptation and re-action of existing structures (anvil, hammer bone). Bi Shundong, one of the corresponding authors of the paper and a professor at Yunnan University, told China Science News.

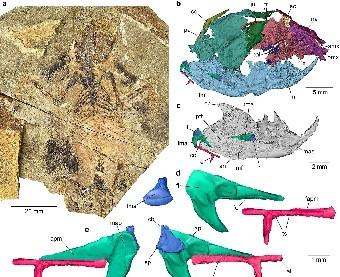

The study discovered the theory of the anvil-hammer superimposed relationship, which solved the problem of the mechanism of jaw movement. The specimen from the Late Jurassic Yanliao biota (about 160 million years ago) in Qinglong County, Hebei Province, belongs to the double-bowled coronate, which has a gliding wing membrane and is a species of thief beast.

"The two sides of the specimen preserve in situ the intact ossicles and joint structures, in which the anvil is only about 1 mm long, which is very rare." Wang Jun, the first author of the paper and the Inner Mongolia Museum of Natural History, said.

The middle ear contains three ossicles of hearing—the stapes, anvils, and hammer bones—the smallest bones in the skeletal system of living mammals, including humans, forming an auditory chain that transmits sound waves and enhances sound wave frequencies from the eardrum to the inner ear. In contrast, reptiles have only one stirrup in the middle ear, while the joint bone in their jaw and the square bone in the skull form a jaw joint, connecting the lower jaw and the skull, with the dual functions of chewing and hearing.

In the process of reptile evolution into mammals, square bones and joint bones gradually evolved into anvil bones and hammer bones, forming the keen auditory structure of mammals that are now "three bones standing". However, exactly how the square and articular bones of reptiles separated from the mandibular and evolved into the delicate and complex ossicles of mammals has been considered a central problem in the study of biological evolution for the past two hundred years.

Traditional models of middle ear evolution suggest that the lower jaw of mammalian ancestors was connected to the skull by Mychonnearthys and articular bones, and that the enlargement of the skull during mammalian evolution led to the position of the middle ear moving backwards and eventually detaching from the lower jaw. Recent studies have proposed the "motor function drive theory", which believes that the behavior of the jaw moving backwards when polyodonts chew is the main reason why the middle ear gradually detaches from the lower jaw and eventually enters the skull. However, the mandibular, which is connected to the skull by mychondrium and articular bone, does not move backwards, and the basal mammalian clades such as platypus do not move backwards when chewing, contradicting the theory of motor function drive.

Through the study of the fine morphology and joint structure of the ossicles, it was found that the ossicles of the thief were obviously separated from the lower jaw, and there was no mychondrium attached, which belonged to the typical mammalian middle ear. The two ossicles, the anvil bone and the hammer bone, like the living platypus, are superimposed. It is this overlapping connection that allows for small movements between the anvil and the hammer bone, thus providing space for the movement of the lower jaw relative to the skull, which ultimately leads to the complete separation of the ossicles from the lower jaw.

This way of connecting the upper and lower ossicles of hearing, first appeared in the early members of various branches of Mesozoic mammals, and was also seen in the early stages of the ontology of living platypus (single-hole), placental and marsupials, and was a key part of the transition of the middle ear ossicles from having the dual functions of chewing and hearing to a single auditory function.

This superimposed connection, further in the Cretaceous true trilobites, polyodonts, and paraodonts, moved the anvil backwards relative to the position of the hammer bone to form a partial overlap. In the long years that followed, these two small ossicles were completely separated from the lower jaw and continued to shrink into the middle ear and full-time hearing, becoming true mammalian ossicles. It can be seen that it is natural selection, not the jaw-chewing function, that determines the evolution of the middle ear.