@Pierluigi Long

Federico Fellini and the Lost Cinematic Magic

Author: Martin Scorsese

HARPER's MAGAZINE

Translated | gyro

Typography | room temperature dog

©️ Except for the attribution, the pictures are from the Internet

00

Eighth Avenue, New York, 1959, in the afternoon, exterior

The camera kept moving, on the shoulders of a young man, a teenager, intently walking westward on the busy Greenwich Village Boulevard.

Under one arm, he was holding several books. In his other hand, he holds a copy of The Voice of the Countryside.

He walked quickly, past men in coats and hats, past women pushing foldable shopping carts in scarves, past couples holding hands, past poets, cheaters, musicians, and drunkards, past grocery stores, liquor stores, delis, apartment buildings.

But the young man's eyes were focused on one thing: the door number of the Arts Theatre, where John Casaverti's Shadow and Claude Chabrol's Cousin were playing.

He mentally wrote it down, and then crossed Fifth Avenue all the way west, past bookstores, record stores, recording studios, and shoe stores, until he reached the Eighth Street Theater. "Flying Geese" and "Love in Hiroshima", as well as Jean Luc Godard's "Exhausted" are coming soon!

The camera continued to follow him, and as he turned left on Sixth Avenue, he hurried past restaurants, more liquor stores, newsstands, and a cigar shop, then crossed the street and saw the door sign of the Waverly Theater that read: "Ashes and Diamonds."

He cut back east from West Fourth Street, past the Kettle of Fish and the Judson Memorial Church south of Washington Square, where a man in a linear suit was handing out flyers. Fur-clad Anita Eckerberg and La Dolce Vita will be performing at a broadway theater, selling reserved seats at Broadway ticket prices!

He walked along LaGuardia Square to Bleecker, past Village Gate and Bitter End, to the Bleecker Street Cinema, where "In the Mirror," "Shoot the Pianist, and Twenty Years of Love," and "Night," which has been screened for three months, is screening!

He lined up to see Truffaut's films, opened his Country Voice magazine and flipped into the movie section, and a lot of wealth jumped out of the pages and swirled around him: "Winterlights", "Pickpockets", "Devil's Eyes", "Falling into a Trap", Andy Warhol's screening, "Pigs and Warships", Kenneth Anger and Stan Brahag's conversation in the Anthology Film Archives, "Eyeliner"... More important than everything else in all this:

Poster of the French version of "Eight and a Half Parts"

Joseph M. E. Levin introduces Federico Fellini's Eight and a Half!

As he flipped through the pages, the camera rose above him and the waiting crowd, as if stirring in waves of their excitement.

01

Fast forward to today's film art, which is being systematically degraded, marginalized, and reduced to the cheapest common denominator: "content."

Just fifteen years ago, the word "content" was heard only when people were seriously discussing the art of cinema, and it was contrasted and measured against "form". Later, gradually, it was increasingly used by those who took over media companies, most of whom knew nothing about the history of the art form and didn't even think they should know.

"Content" became the business term for all moving images: a David Lane movie, a cat video, a Super Bowl commercial, a superhero movie sequel, an episode of a series.

Of course, it has nothing to do with the cinema experience, but with home viewing. On streaming platforms, it has completely replaced the cinema experience, just as Amazon has replaced brick-and-mortar stores.

A streaming platform that has swept the world

On the one hand, it's good for a lot of filmmakers, myself included.

On the other hand, it creates a situation where everything is presented to the audience on a level playing field, which sounds democratic, but it's not. If further viewing is "suggested" by an algorithm based on something you've already seen, and those suggestions are based solely on the subject matter or genre, what effect does this have on cinematic art?

Curation is not undemocratic, nor is it "elitism", a term that is now used too often and has no meaning. It's an act of generosity: you're sharing what you love and what inspires you (the best streaming platforms like Critterion Channel and MUBI, and traditional channels like TCM, are all curated based: they're actually all curated).

Algorithms, as the name suggests, are based on computations that treat the viewer as a consumer, not anything else.

Publishers like Amos Vogel, the choices made by Grove Press in the sixties, were not only acts of generosity, but often acts of bravery. Dan Talbot, both distributor and curator, founded New Yorker Films to release a film he loved: Bertolucci's Eve of the Revolution.

This is not a safe bet. Thanks to the efforts of these people and other distributors, curators, and theaters, these films that came to the United States made an extraordinary moment.

But the circumstances that created that moment are gone forever, both in terms of the primacy of the cinematic experience and the shared excitement of the infinite possibilities of cinematic art.

That's why I often think back to those years. I feel fortunate that I have always been young and alive, with an open mind when everything happens. Cinematic art has always been more than content, and it will never be. In those years, those films popped up from all over the world, interacting with each other every week and redefining the art form, as evidenced by that.

Essentially, these artists are constantly grappling with the question "What is a film?" That's the question, and then throw it back to the next movie to answer. No one operates in a vacuum, and everyone seems to be responding and inspiring others. Godard, Bertolucci, Antonioni, Bergman, Imama, Ray, Casaveti, Kubrick, Varda, Warhol and others reinvent the film with every new camera movement and every new clip, while veteran filmmakers like Wells, Bresson, Houston, and Visconti were rekindled by the surge of creativity around them.

02

At the center of it all, there is a director, an artist, whose name is synonymous with cinema and refers to where cinema can reach.

The name immediately conjures up a certain style, a certain attitude towards the world. In fact, it became an adjective. Let's say you want to describe the surreal atmosphere of a dinner party, wedding, funeral, or political conference, or the madness of the whole planet: you just say the word "Fellini" and people will understand what you mean.

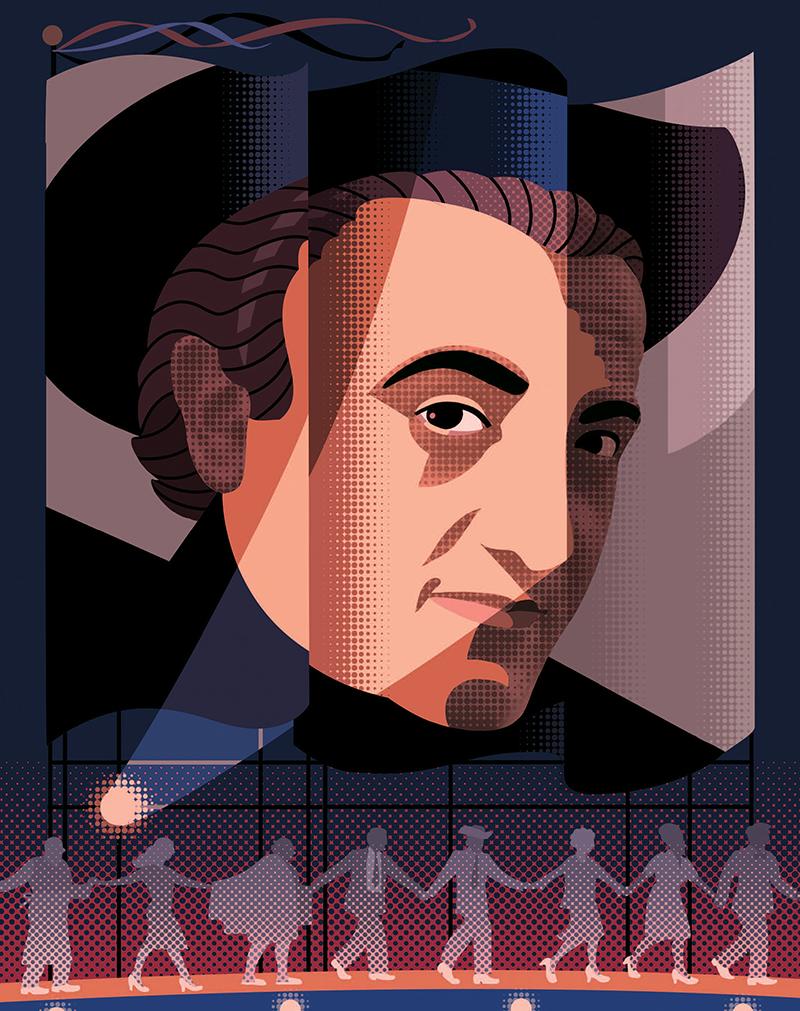

Young Fellini

In the sixties, Federico Fellini became more than just a filmmaker. Like Chaplin, Picasso and the Beatles, he was more important than his own art. At some point, it's no longer a question of this film or that movie, but all the movies that come together and become the act of chiseling in the galaxy.

Going to see a Fellini movie is like listening to Callas sing, going to see an Olivier show or Noureyev dancing. His films even began to incorporate his name: Fellini Satyricon and Fellini's Casanova. The only comparable example in the film world is Hitchcock, but that's something else: a brand, a genre in itself. Fellini is a master of the arts in the world of cinema.

By now, he had been gone for nearly thirty years. The moment when his influence seemed to permeate all cultures was long gone. That's why Critterion's boxed Essential Fellini, launched last year to mark the centenary of his birth, was so popular.

CC's hot Fellini set

Fellini's absolute control over the visual began in 1963's Eight and a Half Films, in which the camera hovers, floats, and soars between internal and external realities, in line with the emotional changes and secret thoughts of Fellini's self-cast "Guido" played by Marcelo Mastruani. There are some passages in this movie that I've revisited many times, but I still find myself thinking:

How did he do it? How did he do it? Why does every movement, gesture, and gust seem to fit perfectly? Why does all this feel incredible and inevitable, like a dream? Why is there such a rich and inexplicable vision at every moment?

Sound plays a big role in this mood.

As with the imagery, Fellini's sound design is equally creative. Italian cinema has a long tradition of non-synchronous sounds, beginning in the Mussolini period, when he ordered that all films imported from other countries must be dubbed. In many Italian films, even in some great films, the dissynchronization of the sound can be disorienting. Fellini knew how to use this sense of disorientation as a tool of expression. The sounds and images in his films work together and reinforce each other, so that the entire film experience flows like music, or like a huge picture that slowly unfolds.

Nowadays, people are dazzled by the latest technological tools and their features. But lightweight digital cameras and post-production techniques like digital stitching and deformation don't create movies for you— they create movies with all the choices you make throughout the film.

For the greatest artist like Fellini, no element is too small: everything matters. I'm sure he'll be thrilled by the lightweight digital cameras, but they won't change the rigor and precision of his aesthetic choices.

It is important to remember that Fellini started with Neorealism, which is interesting because in many ways he represents the poles of Neorealism. He was actually one of the inventors of neorealism, collaborating with his mentor Roberto Rossellini. I'm still blown away by it. It has brought a lot of inspiration to the film industry, and I doubt that without the foundations of neorealism, all the creativity and exploration of the fifties and sixties would still have happened. It's not so much a movement as it is a response from a group of film artists to an unimaginable moment in their national life.

Fellini (right) and Rossellini (left) @Sense of Cinema

After 20 years of fascism, after so much cruelty, terror and destruction, how do people move forward as individuals and as a nation?

The films of Rossellini, Desika, Visconti, Zavatini, Fellini and others, aesthetically integrated with morality and spirit, cannot be separated, and play a vital role in the world's eyes of Italian redemption.

Fellini co-authored Rome, the Undefended City and Fire of War (fellini was said to have taken over several scenes when Rossellini fell ill), and he co-wrote and starred in Love with Rossellini. His path as an artist was clearly at odds with Rossellini from the beginning, but they maintained great mutual love and respect.

Fellini once said something very pithy: what people call neorealism really exists only in Rossellini's films, and does not exist anywhere else.

Leaving aside Bike Thief, Tears of the Wind and Tears, and The Earth Is Fluctuating, I think Fellini means that Rossellini is the only person who has such a deep and enduring trust in simplicity and humanity, the only one who strives to bring life itself as close as possible to telling his own story. Fellini, by contrast, is both a stylist and a fable, a magician and a storyteller, but the life experience and ethical foundations he gets from Rossellini are crucial to the core of his films.

Rossellini with cats

I grew up when Fellini was developing and blooming as an artist, and many of his films are precious to me. When I was 13 years old, I watched The Great Road, the story of a poor young woman being sold to a charlatan, and it touched me in a special way. It's a film set in postwar Italy, but unfolds like a medieval ballad, or something older, a divergence from the ancient world. I think "La Dolce Vita" can say the same thing, but it is a panorama, a grand event of modern life and spiritual rupture. Released in 1954, The Great Road (released in the United States two years later) is a smaller canvas, a fable based on elements: earth, sky, innocence, cruelty, affection, destruction.

For me personally, it has an extra meaning.

The first time I watched it was on TV with my family, the story is a true reflection of the hardships my grandparents left behind in their hometown. The Main Road is not popular in Italy. For some, it was a betrayal of neorealism (many Italian films at the time were judged by this standard), and I think it was just too strange for many Italian audiences to set up such a harsh story within the framework of an allegory.

Yet in other parts of the world, The Great Road was a huge success and was a truly fellini film. Fellini seems to have put the most effort into the film and suffered the most – his script was very detailed, six hundred pages long, and at the end of an extremely difficult production, he had a psychological breakdown and had to go through the first (as I remember) of many future psychological counseling to finish shooting. This is also the movie he cares about the most in the rest of his life.

"The Great Road"

The Night of Cabilla is a series of fantastic episodes of Rome's street life (the inspiration for the Broadway musical and the Bob Fox film The Melody of Life) that cemented his reputation.

Like everyone else, I feel like it's too emotionally powerful. But the next great creation is La Dolce Vita.

When the film was first released, watching the film with the audience was an unforgettable experience. In 1961, "La Dolce Vita" was released here by Astor Pictures and screened as a special event at a Broadway theater, with reserved mail-order seats and high-priced tickets: a screening similar to watching a Biblical epic such as Bing hue.

We sat down, the lights went out, and watched as a majestic, terrifying movie mural unfolded on the screen, and everyone present experienced that shock. It is an artist who successfully expresses the anxiety of the nuclear age, feeling that everything no longer matters because everything and everyone can be wiped out at any time. We felt the shock, but we also felt Fellini's love for the art of cinema – and therefore, for life itself.

Rock 'n' roll has seen similar situations, like Bob Dylan's first electronic album, followed by The White Album and Let It Bleed: they're about anxiety and despair, but they're exciting and otherworldly experiences.

Ten years ago, when we were in Rome to introduce the restoration of La Dolce Vita, Bertolucci was in attendance. He was in constant pain because he was in a wheelchair, but he said he had to be there. After the movie, Bertolucci confessed to me that "La Dolce Vita" was the reason why he turned to film in the first place. I was really surprised because I had never heard him discuss this. But in the end, this is not surprising. That movie was an uplifting experience, like a shockwave that traveled through the entire culture.

"La Dolce Vita"

Fellini's two films that have had the greatest influence on me, and the ones that really stuck in my heart were "The Wandering" and "Eight and a Half Films" and "Eight and a Half Films" in my heart.

"Wandering" is because it captures something so real and precious that is directly related to my experience.

And "Eight and a Half" is because it redefines my view of cinema: what movies can do and where they can take you.

Released in Italy in 1953 and in the United States three years later, Wandering was Fellini's third film and his first truly great film. It is also one of his most personal works. The story follows a series of life scenes from five friends in their 20s in Rimini, the city where Fellini grew up. Alberto, played by the great Alberto Soldi; Leopoldo, played by Leopoldo Trieste; Morado, Fellini's self-projection, played by Franco Interrangi; Ricardo, played by Fellini's brother; and Fausto, played by Franco Fabrizi. They play billiards all day long, chase girls, and wander around making fun of others. They have grand dreams and plans. They act like children and their parents treat them accordingly. And life goes on.

I feel like I know these guys, from my own life, from my own neighborhood. I can even recognize some of the same body language, the same sense of humor. In fact, at some point in my life, I was one of these people.

I understand what Morado went through, his eagerness to flee. Fellini captured it all very well, immaturity, vanity, boredom, sadness, looking for the next distraction, the next point of excitement. He made us feel warmth, camaraderie, jokes, sadness and inner despair. "Wandering Child" is a sad, lyrical and bittersweet film, and it is a key inspiration for "Poor Streets and Dark Alleys". This is a great movie about hometown. Anyone's hometown.

"Poor Streets and Dark Alleys"

03

As for "Eight and a Half Parts". Everyone I knew in that era had a turning point, a personal touchstone.

My touchstone—and it still is—Eight and a Half Parts."

What would you do when you made a movie like La Dolce Vita that took the world by storm? Everyone is paying attention to your every word and deed, waiting to see what you are going to do next. That's what Dylan was like in the mid-sixties after "Blonde on Blonde." For Fellini and Dylan, the situation is the same: they have touched countless people, and everyone feels like they know them, understand them, and often feel like they have them.

So, pressure from the public, pressure from fans, pressure from critics and enemies (and fans and enemies often feel like they are one). The pressure to make them create more similar works. Pressure to go further. Pressure from yourself, pressure on yourself.

For Dylan and Fellini, the answer is to venture inward. Dylan sought what Thomas Merton called simplicity in the spiritual sense, and he found simplicity after the motorcycle accident in Woodstock, where he recorded The Basement Tapes and wrote songs for John Wesley Harding.

Fellini started with his situation in the early sixties and made a film about his artistic decomposition. In doing so, he embarks on an adventurous exploration of uncharted territory: his inner world.

Fellini's self-projection "Guido" is a well-known director who is suffering from the creative obstacles equivalent to that of a writer, as an artist and a human being, he is looking for a refuge, looking for calm, looking for guidance. He went to a lavish spa sanatorium to "heal", where his mistress, his wife, his anxious producer, his actors, his crew, and a clutter of fans and followers, as well as fellow spa goers, soon descended into his convalescence—one of whom, one critic, declared that his new script "lacked a central conflict or philosophical premise" and amounted to "a series of senseless plots." The stress intensifies, his childhood memories, longings and fantasies come and go in his day and night, and he waits for his muse (who comes and goes in the form of Claudia Katina) to "create order" for him.

"Eight and a Half" is a brocade woven from Fellini's dreams. Just like in a dream, on the one hand everything seems solid and clear, and on the other hand it appears to be floating and short. The tone is constantly changing, sometimes drastically. He actually creates a visual stream of consciousness that keeps the viewer in a state of surprise and alertness all the time, and the form is constantly redefining in progress. You're basically watching Fellini make a movie in front of your eyes, because the creative process is the structure.

"Eight and a Half Parts"

A lot of filmmakers are trying to do something along that line of thinking, but I don't think anyone can do what Fellini does here. He has the courage and confidence to play with every creative tool, extending the plasticity of the image to everything that seems to exist on some subconscious level. Even the seemingly most neutral picture, when you really look closely, there are elements in the lighting or composition that shock you because in some way injects Guido's consciousness. After a while, you stop trying to figure out where you are, whether you're dreaming or flashbacking, or in ordinary reality. You want to get lost and wandering with Fellini, surrendering to the authority of his style.

The picture culminates in the scene where Guido and the Cardinal meet in the baths, a journey through the underworld in search of the oracle and a journey back to the dirt we all originate from. Throughout the film, the camera is moving: restless, hypnotic, floating, always moving toward something inevitable, something revelatory. As Guido walked downstairs, we saw from his perspective a succession of people coming toward him, some suggesting how he could please the Cardinal, others begging him for help. He entered a steam-filled vestibule and walked toward the Cardinal, whose entourage held up a tulle shield before him, for the Cardinal was undressing and we could only see his shadow.

Guido told the Cardinal that he was unhappy, and the Cardinal's answer, simple and unforgettable—

"Why should you be happy? That's not your task. Who told you that we came into this world to be happy? ”

Every shot of this scene, every arrangement and choreography between the shots and the actors, is extremely complex. I can't imagine how difficult it would be to execute all of this. On screen, its unfolding is so elegant that it looks like the easiest thing in the world.

For me, the audience with the Cardinal embodies the extraordinary truth of "Eight and a Half Parts": Fellini made a film about cinema, which can exist only as a film and not as anything else, not as a piece of music, not as a novel, not as a poem, not as a dance, only as a film work.

When "Eight and a Half" was released, people debated it endlessly, and the effect was so dramatic. Each of us has our own interpretation, and we spend hours talking about the film: every scene, every second. Of course, we have never determined a clear explanation—only a dream can be explained by the logic of a dream. The film doesn't have a clear explanation, which bothers a lot of people. Gore Vidal once told me that he said to Fellini, "Fred, the next time you dream less, you must tell a story." ”

But in Eight and a Half, there is no explanation, because there is no explanation for the process of artistic creation: you have to keep going. When you're done, you'll have to do it again, like Sisyphus. As Sisyphus discovered, pushing boulders up the mountain again and again becomes the purpose of your life.

The film had a huge impact on filmmakers: it inspired Paul Mazursky's The Dramatic Life, in which Fellini still appeared as his real character; Woody Allen's Once Upon a Time in Stardust; and Fox's Jazz Spring, not to mention the Broadway musical Nine. As I said, I've watched Eight and a Half times countless times, and I can't even talk about how much it has affected me. Fellini has given us all a glimpse of what an artist is and the super demand to create art. "Eight and a Half" is the purest expression of love for the film I know.

After La Dolce Vita? Hard.

After "Eight and a Half Parts"? I can't imagine.

With Damn Toby, a mid-to-length film inspired by Edgar Allan Poe's story (the last third of a platter film called Ghost in the Shell), Fellini elevates his hallucinatory imagination to a sharper level. The film is an instinctive descent into hell. In Fellini's The Myth of Love, he created something unprecedented: a mural of the ancient world, as he put it, "inverse science fiction."

Armacord is a semi-autobiographical film set in a fascist Rimini and is now one of his favorite films (Hou Hyo-hyun loved it, for example), though it was far less daring than earlier films. But it is still a work full of extraordinary vision (I was surprised by Italo Calvino's appreciation of the film, which he thought was a portrayal of Italian life during Mussolini's time, which I did not expect).

After Armacord, each fellini film had brilliant fragments, especially Casanova. It's a cold film, colder than Dante's deepest hell circle, and its style is extraordinary, bold, but really daunting. This seems to be a turning point for Fellini. In fact, the late seventies and early eighties seemed like a turning point for many filmmakers around the world, including myself. The camaraderie we all felt, real and imagined, seemed to be shattered, and everyone seemed to be on their own silos, fighting for the next film.

I know Federico enough to call him a friend. The first time we met was in 1970, when I took a group of short films of my choice to a film festival in Italy. I contacted Fellini's office and he gave me half an hour. He was so enthusiastic, so gracious. I told him that on my first trip to Rome, I had left him and the Sistine Chapel for the last day of the visit. He laughed. "Look, Federico." His assistant said, "You've become a monument to boredom!" I assured him that boredom was one thing he would never be. I remember I also asked him where he could find a good lasagna, and he recommended a great restaurant: Fellini knew all the best restaurants everywhere.

A few years later, I moved to Rome for a while and I started seeing Fellini regularly. We would meet each other and then have dinner together. He was always a performer, and the performance never stopped. Watching him direct a film is an extraordinary experience. It was as if he was conducting more than a dozen orchestras at the same time. I took my parents to the set of "City of Women", and he ran everywhere, coaxing, pleading, performing, sculpting, adjusting every element of the picture to the last detail, and realizing his idea in the uninterrupted whirlpool of motion. As we left, my father said, "I thought we were going to take a picture with Fellini." I said, "It's already done!" Everything happened so fast that they didn't even know what was going on.

Fellini, Isabella Rossellini, Martin Scorsese (from left to right).

In the last years of his life, I tried to help his film Moonsing be released in the United States. On this project, his relationship with the producers was very weak: they wanted a Fellini-style big production, and he gave them something more brooding and melancholy.

I'm really shocked that no distributor wants to touch it, and no one, including any of the major independent theaters in New York, doesn't even want to show it. Old films, yes, but new films, no, turns out this is his last film.

Later, I helped Fellini secure some funding for one of his planned documentary projects, a series of portraits of people who made the film: actors, cinematographers, producers, location directors (I remember in the outline of that episode, the narrator explained that the most important thing was to organize expeditions so that the location could be brought close to a great restaurant). Unfortunately, he died before he could start the project.

I remember the last time I spoke to him on the phone. His voice sounded so faint that I realized he was fading away. I was saddened to see that incredible vitality disappear.

The set of "Love Myth"

Everything has changed – (like) the movie and its importance in our culture.

Of course, it's not surprising that artists like Godard, Bergman, Kubrick, and Fellini, who once ruled our great art forms like gods, end up in the shadows over time.

But in the moment, we can't take everything for granted. We can't rely on the film industry to take care of the art of cinema. In the film industry, that is, the current mass visual entertainment industry, the emphasis is always on the word "industry", and the value is always determined by the amount of money made by any particular property right: in this sense, from "Sunrise" to "The Road" to "2001: A Space Odyssey", it can only dry up day by day in the "Art Movie" channel on the streaming platform, and no one cares.

Those of us who understand the art of cinema and its history must share our love and knowledge with as many people as possible. We need to make it clear to the rightful owners of these films that they are not just property that is exploited and then locked up. They are one of the greatest treasures of our culture and must be treated accordingly.

I think we also have to refine our concept of what is and what is not a movie. Federico Fellini is a great place to start. You can say all sorts of things about Fellini's films, but one thing is indisputable: they are films.

Fellini's work has made a significant contribution to the definition of the art form of cinema.