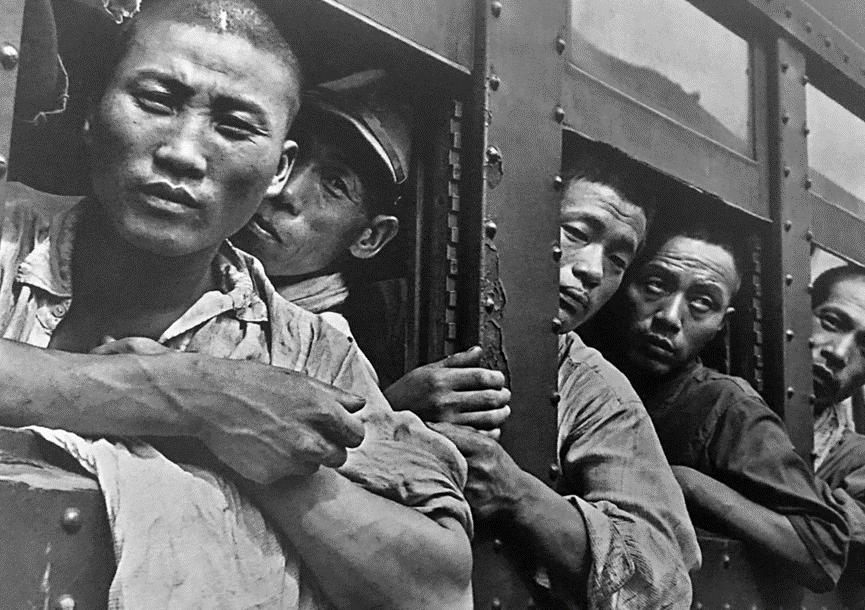

In early 1946, 594,000 strong Japanese prisoners of war of the Kwantung Army were squeezed into a series of stuffy tank trucks and taken to the bitter cold of Siberia to engage in "labor reform."

The soldiers lacked food and clothing, worked hard every day, and had to undergo ideological reform and repentance. The days were too difficult, and the prisoners of war died in droves of starvation and cold.

From the end of 1946, the Soviet army successively repatriated prisoners of war from the Kwantung Army. Due to the low enthusiasm of Japan to receive it, it was not until the end of December 1956 that the repatriation came to an end.

A total of 472,934 Japanese prisoners of war returned home and 62,068 died in Siberia.

When these prisoners of war returned home from their ordeal, the japanese authorities and the people's attitude toward them was perhaps far more harsh and chilling than the cold Siberian wind.

Their veteran status is not recognized, there is no pension, preferential treatment, everywhere hit the wall, repeatedly blindfolded, most people can not even find a job.

Many homeless soldiers had to sleep on the streets, and some became homeless.

However, the general-ranked officers among the prisoners of war, as well as the relatives of some dignitaries, were properly placed.

To the surprise of the Japanese authorities, more than 180 of the people who were resettled were plotted against in the prisoner-of-war camp and became Soviet spies. After their return, they played a major role in the intelligence work of the Soviet Union.

However, the good times did not last long, and in 1954, all the spies were exposed.

The cause came from a mercurial move by Beria, the number two person in the Soviet Union.

<h1>Shame on the red face</h1>

Beria, a member of the inner circle of the Soviet Union, was in charge of the People's Commissariat of internal affairs of the SOVIET Union for a long time and held the power of life and death.

Figure | Beria

There are so many stories of Beria's moral corruption that Russia has refused to rehabilitate him. In 1998, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the remains of five young women were found at Beria's former residence on Moscow's "Garden Ring".

In 1946, Beria took a fancy to the ballerina Andrivna Gudova, took her for herself, moved her family into the General's Building in downtown Moscow, and sent her husband to Japan, nominally to work in intelligence.

Gudova's husband, Yuri A. Rastrov, a KGB lieutenant colonel.

Rastrov was born on July 11, 1921 in Dimitryevsk, a small town in the Kursk Oblast——— the son of a Soviet General of the Red Army who served as a political commissar of the Dakarn Front in Moscow and a physician to a physician.

In 1941, many of his peers were paid for, but Rastrov was much luckier and, because of his father's connections, was recruited into the NKVD and went to the secret service base to learn Japanese.

After graduating, Rastrov entered the foreign intelligence service, later married the ballet actress Andrivna Gudova, and in 1945 gave birth to the eldest daughter, Tatjana.

In 1946, he was sent to Japan to take cover as a diplomat to gather intelligence on U.S. troops in Japan.

After less than half a year, he returned to the Soviet Union on the grounds that his identity was in danger of being exposed.

The real reason is that he can't trust his wife.

Rastrov knew that with the rank of lieutenant colonel, he was able to live in the General's Building not because of his achievements in intelligence work, but because Beria had a plan for his beautiful wife.

However, the arms can't twist the thighs. Soon after, he was sent again to Japan.

Before leaving, the director personally talked to him: for the sake of competing for influence in the Far East, intelligence activities against Japan should not be weakened, but should be strengthened.

The director personally handed him a list of 36 people, all of whom were relatives of generals and dignitaries among the Kwantung Army prisoners of war, who had been plotted against him as Soviet spies in the prisoner-of-war camp and who had now returned to Japan.

His secret mission was to use a tennis club in Tokyo as a base to contact the 36 spies and pass on information.

The director also beat him, a man should put his career first, do not have children and daughters, complete the task in Japan as scheduled, and promote the general is expected; otherwise, accept disciplinary sanctions.

Rastrov was forced to return to Japan, perhaps taking advantage of the convenience of his work to perfect his tennis skills.

On the tennis court, he inadvertently revealed to a friend that he "wanted to learn English."

Soon, a beautiful "blonde female teacher" floated to his side.

As an agent, he knew in his heart that the other party's identity was suspicious. However, frustrated by the love scene, he did not break it, but established an ambiguous relationship with the other party.

On 17 December 1953, TASS abruptly announced that Beria had been removed from all positions and brought before the court.

Two days before Rastrov was happy, terrible news came that all those associated with Beria would be subject to "scrutiny."

Rastrov was surprised to find that he could no longer contact his wife.

In January 1954, Rastrov was notified to return to the Soviet Union on January 25.

With a look of schadenfreude, the translator said to him: "As soon as winter arrives, the shrimp will not be able to jump up!" ”

He realized that as soon as he returned home, his life would be over.

On the evening of January 24, 1954, the day before returning home, Rastrov found a "female teacher" ——— a female CIA agent.

Soon, he and the "female teacher" boarded a plane to Okinawa, and then they stopped and flew to the United States.

In the United States, Rastrov and Pan revealed all the secrets——— there were as many as 36 Japanese in direct contact with him in Tokyo, and he also listed specific names, including former chief staff officer of the Japanese base camp, Asae Fuharu.

Figure | Spring towards the branches

In November and December 1954, Rastrov signed his real name and published a serial article in the American magazine Life revealing the inside story of the KGB and the causes and consequences of his defection to the West.

The article had a wide impact. Rastrov was known as the Soviet Union's "No. 1 spy" in Asia, and as a result of his rebellion, Soviet spies in Japan were almost wiped out.

Subsequently, the Moscow military tribunal sentenced him to death in absentia.

But what is puzzling is that after the serial article was published, Rastrov mysteriously disappeared from public view.

In 1956, he appeared briefly to attend the hearings of the US Senate Subcommittee, but in the decades that followed, Rastrov completely "evaporated"!

Some people wonder if Rastrov was "hoeed" by Soviet agents abroad.

<h1>A life in seclusion</h1>

On January 19, 2004, just five days before the 50th anniversary of Rastrovrov's defection to the United States, at a rehabilitation hospital in McNorkent on the picturesque Potomac River in the United States, an elderly American named Martin Simon died of illness at the age of 83.

In the eyes of friends, Simon is a businessman who likes Russian-style meat stuffed vegetable rolls, a skilled tennis player, but no one expected that a Russian magazine published in September would throw out a surprising news: the so-called "Martin Simon" is actually the former Soviet Union's Agent No. 1 in Asia - Yuri Simon. Lieutenant Colonel A. Rastrov, also a traitor that the KGB has been secretly pursuing! In 1954, he single-handedly destroyed the entire Soviet spy network in Asia.

A few days later, Rastrov's daughter Jennifer Wasser showed up in an exclusive interview with the Post, revealing the inside story of her father's "double life."

It turned out that not long after Rastrovrov defected, he appeared in a completely new guise- Martin V. F. Simon.

Figure | Yuri M. A. Rastrov

In order to hide the sky, the CIA also made up a set of "files" for Simon that "have noses and eyes".

In 1959, Simon officially acquired U.S. citizenship, a Social Security number, and a book with the inscription "Martin S. Simon" written on it. F. Simon's U.S. license.

With this license, Simon often travels to European ski resorts in winter.

Accompanying her was the CIA "female teacher", Hope Maccartney Simon, who married Simon and gave birth to two daughters.

His wife and daughter, who had been stranded in the Soviet Union, had to endure the pain of separation for many years, and later, his wife, the ballet dancer Andrivna Gudova, finally announced her divorce from him.

According to his daughter Wasser, his father was always secretive about his past experiences.

It wasn't until she was 11 that she and her 13-year-old sister Alexandra learned of her father's dual identity, when the family was living in Minnesota.

One day, the mother solemnly told the sisters, "You have a sister in the Soviet Union."

Wasser said Simon was annoyed by his wife's approach. Doing so is likely to leak out and put the family in extreme danger. At that time, the KGB was pursuing him with all its might.

Talking about the past, Wasser said: "At that time, my father may have been a little worried, but his worries were not unreasonable. Life and death are at stake, and we cannot do so without caution. ”

According to Wasser, his father may have been active on the front lines, providing the CIA with a lot of advice and advice.

In a declassified CIA document, Rastrov was described as a "high-value spy talent" who "provided inside and background information on a large number of KGB and Soviet authorities, and he was a mentor to young CIA agents who taught them how to deal with the KGB." ”

Paul Raymond, the now retired head of the CIA's counterintelligence department, said: "In counter-espionage work, he has helped a lot in how to identify the 'mole'. ”

"My father often took long-haul planes to meetings out of town to prevent revealing his location," Wasser said. He never shared the slightest detail of his work with his family. ”

Even after the collapse of the Soviet Union, he remained in a state of fear.

Wasser said she would like to see her sister in the Soviet Union in her lifetime.