<h1 class="pgc-h-arrow-right" data-track="6" > a grape wine luminous cup</h1>

Grape wine luminous glass, want to drink pipa immediately urge. Drunkenly lying on the battlefield Jun Mo smiled, how many people did Gu Lai fight back?

Wang Han (Tang) "Liangzhou Words"

The Liangzhou Ci by the poet Wang Han in the eighth century AD is a well-known work of Classical Chinese literature. During the prosperous Tang Dynasty, the territory of the Tang Empire expanded to the distant western regions, and the Tang army also had to fight in a foreign country thousands of miles away from its hometown, which became the poetry described in the "Liangzhou Ci".

In addition to depicting the military career and the dangers and bitterness of expeditions to other places, the words also describe many foreign cultures, such as the "grape wine" imported from the Levant and the Caucasus, and the "pipa" introduced by the nomadic Hu people in Central Asia.

It is worth mentioning that the words describe a mysterious "Luminous Cup", which has attracted countless speculations from later generations. What exactly is a luminous cup? Over the years, the academic community has put forward a lot of speculation and discussion about this. Some people say it's a white jade cup, and some people say it's a glass. Whatever the truth, it is still controversial to this day.

The Tang Dynasty poet's description of the Luminous Cup must be understood in the context of the entire historical background at that time. If it is really glass, then we can find clues from the Tongdian of ancient Chinese literature written in the ninth century AD, that is, about a century later than Wang Han.

The relevant records in the General Canon are quoted from the Jingxingji, and the origin of the Jingxingji should be mentioned here. Du You, the author of the Tongdian, had a nephew named Du Huan, who was a prisoner of war at the Battle of Qiluo.

Duhuan was captured and exiled to the Arab world, and there is even speculation that he once reached Al-Andalus in southern Spain, which was then controlled by Islamic forces. Later, Du Huan was allowed to return to China, and he wrote his experience and experience in the West into the "Records of The Classics".

At that time, the Tang court allowed foreigners to come to China to become officials, but did not allow the Tang people to go abroad privately, and crossing the border without permission was a felony in the Tang Law, so Du Huan's experience was really difficult, and it was also a window for the Central Plains people to peek into the Western world.

At present, although the "Jing Xing Ji" is unfortunately lost, it has been cited in part by Du Huan's uncle Du Youzhi's "General Code" and has been passed down to this day. The General Classics quote the Book of Jingxing as saying that the Forbidden City in the West is "the one who is in the glass, the mobi under the heavens." (Tongdian vol. 193, Border Defense 9, Xi Rong 5).

FuDiguo, or Ancient Great Qin, is the name given to the Roman Empire in classical Chinese times. As early as the Tang Dynasty, glassware produced in the far west has become famous all over the world. However, to what extent did Roman glass technology develop? Glass magician, why the world Moby? A major archaeological discovery may give us a glimpse of it in modern times.

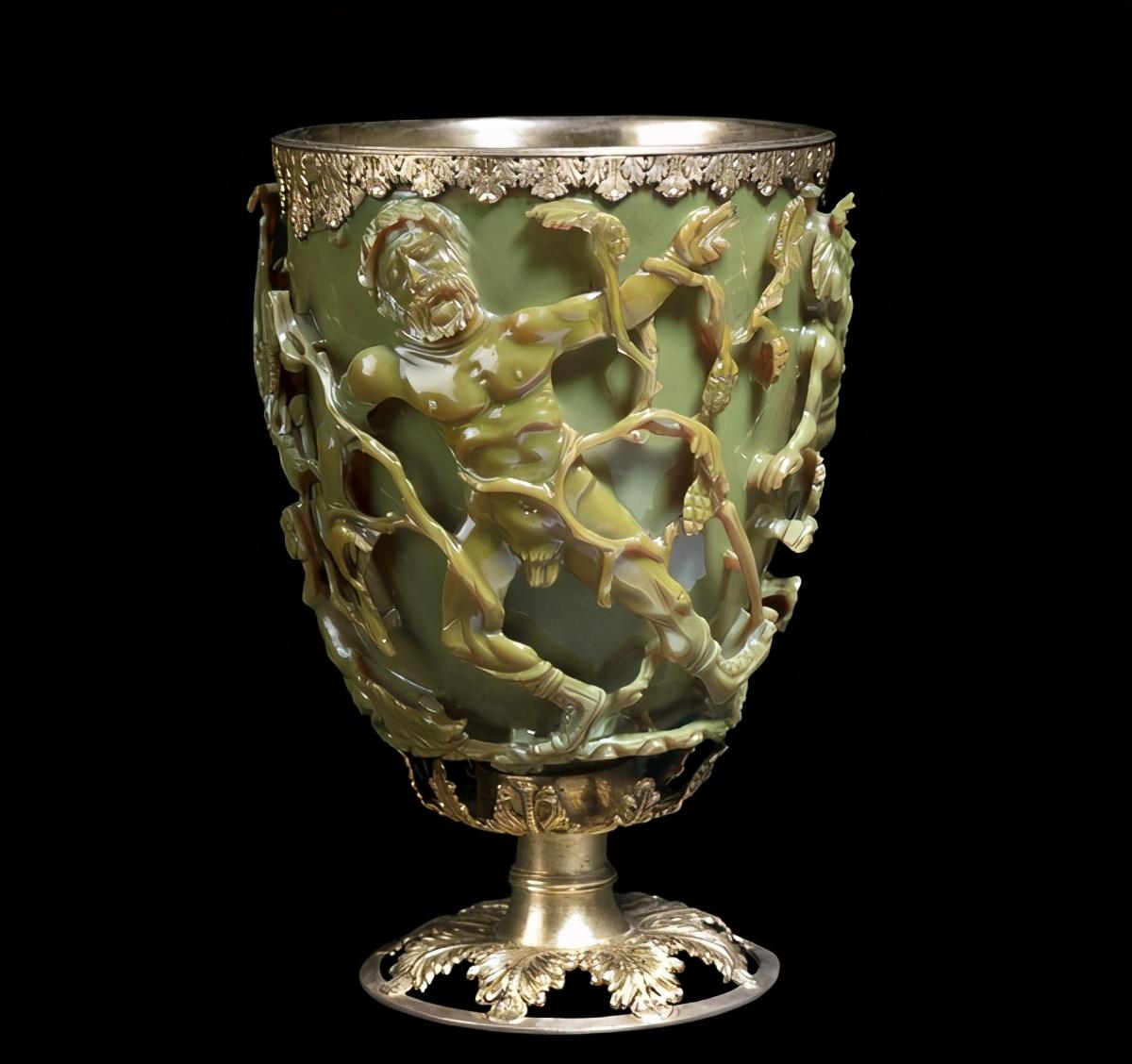

In the classical era exhibition area of The British Museum, there is a glass that is not very conspicuous and is about the same size as an ordinary wine glass, but this ordinary glass has puzzled countless experts and scholars. In daylight, it's just a dark green, opaque ordinary glass with reliefs that, though ingeniously crafted, don't look anything special.

However, if the light source is placed in the cup, the cup body immediately changes, from the ordinary dark green to the eerie purple-red light, just like the red wine in the glass, and like the blood of yin red, the dramatic change of color and light is shocking.

Lekugou

Through the identification of archaeologists, it is believed that the glass should be made in the Roman Empire in the fourth century AD. The relief on the cup is the scene in which Lycurgus, king of Thrace in the sixth episode of the Greek myth of Iliad, is defeated by Dionysus, the ancient Greek god of wine. The reliefs of Laikugu are large and full of cups, and the pattern is vivid, which is why the cup is named Lycurgus Cup.

The Lecugu Cup is one of the treasures of the British Museum's Rome exhibition area, and twentieth-century materials science experts have spent a lot of effort to study the source of the glass's bizarre optical effects, but the truth is still widely disputed.

It was not until the end of the twentieth century, thanks to advances in analytical chemistry such as X-Ray diffraction and electron microscopy, that the secret of the Lekugou Cup was finally revealed.

<h1 class="pgc-h-arrow-right" data-track="25" > the meaning of the lifelike relief on the cup: myth and reality</h1>

With a total height of 16.5 cm and a diameter of 13.2 cm, the Lycugu Cup is currently on display in Hall 41 of the British Museum (European Heritage Zone from 300 to 1,100 AD). At first, scholars made many speculations about the material of the cup, and finally confirmed that the material was glass. When the cup was included in the British Museum, it was only a glass part, and the metal base of the cup was added later, and the most important relief decoration retained the original appearance.

At one end of the glass, Lycugu, the Thracian king, entangled in vines incarnated by Ampercia, frowned, opened his mouth, and his desperate expression came to life. On the other side of the glass, Dionysus, holds a scepter in his hand and attacks Lekugu with a beast

The reliefs on the Lycugu Cup highlight the battle between Lycurgus, king of Thrace (r. around 800 BC) and Dionysus, the Greek god of wine.

Thrace is located in present-day northern Greece, on the northern shore of the Aegean Sea, east of the Sea of Marmara and across the sea from northwest asia minor. The mythical Thracian king Lekugu was a grumpy man who forbade the Thracians to worship Dionysus, angering the Greek dionysus, and eventually sparking a war between the two.

The motif on the cup shows That Lekugou attacking Dionysius and his follower Ambrosia, and Thatposia summons Mother Earth for help, who turns Ampesia into a vine and wraps it around Lekugu to make him unable to move.

Meanwhile, Dionysus, the god of wine, held his staff and fought back with a tiger, repulsing Lekugu and defeating him. This battle of gods and men is deeply etched on the glass, and The face of Laikugu, which is twisted by the vines, is even more vivid, fully reflecting the superb craftsmanship of the glass craftsman.

The Battle of Lecugu and Dionysius on the Cup may have been pointed out to represent a major political event of the time, namely the defeat of Constantine I of the Western Empire in 324 AD by Licinius (reigned 308-324 AD) to re-establish the unity of the Roman Empire. Since the cup was supposed to be of great value at the time, it is not excluded that Constantine I specially ordered it to celebrate his victory.

<h1 class="pgc-h-arrow-right" data-track="35" > the value of the Lekugou Cup</h1>

There are two main reasons why the Lekugu Cup fascinates archaeologists and the materials science community.

The classification of the Lecu cup in ancient Roman glass crafts belongs to the cage cup. The so-called cage cup, refers to the glassware divided into connected inner and outer layers, the outer layer usually has a complex carving, the most common carving is a connected circle or repetitive geometric shape of the relief, looking like a wire mesh cage wrapped cup, hence the name.

Archaeological excavations of cage cups are rare, with only about 50-100 examples to date, with the largest number of them being the Rhine region in western Germany today. Historians believe that cage glasses were also a very expensive luxury in Roman times, and the use of cage glasses was mainly suspended or table-mounted lighting.

The same type of cage cup as the Leku cup, its intricate carving and the method of making intricate three-dimensional geometric patterns have always been a mystery.

Traditional theory is that it was done by blowing two layers of glass inside and out, and some people think that it was made by clay molds, but there is now more and more evidence that the reliefs on such glassware are integrally formed, and use processing techniques that archaeologists have always thought could not exist in Roman times

As scholars took a closer look at the methods used to make cage cups, three competing theories gradually emerged.

The first: the double-layer method, first blowing the smooth surface of the inner layer of cup-shaped glassware, and then making the outer layer of patterns, and then combining the inner and outer layers.

The second: mud mold forming method, all the patterns are first formed in the mud mold, and then injected into liquid glass, after the glass cools and solidifies, you can get the desired shape.

The third: the one-piece forming method, that is, the glass craftsman first blows a single thick-walled glass container, and then grinds and carves point by point to obtain complex concave and convex shapes. Since the outer pattern and the inner container come from the same piece of glass material, it is also called the integrated forming process.

The ring mesh structure of the cage cup is integrated with the cup body, and the extra part is sharpened by the saw knife, leaving only small columnary glass for connection and support

All three of these speculations have their own cities and problems. The first double-layer method must prove that there are traces of melting and re-joining between the inner and outer layers, and the second method of clay mold forming is difficult to explain the hollow characteristics behind the relief portrait of the Laikugu Cup. The third one-piece forming method is also the most difficult to process, which has exceeded the known level of ancient Roman glass manufacturing technology.

Due to the extremely high hardness of glass (grades 6-7), in order for glass to form as a whole, craftsmen need to use sapphire (hardness 8-9) or diamond knives (hardness 10) to process, and it is likely to use mechanically driven tools. In modern times, the same type of machining can only be done by skilled craftsmen who operate electric diamond knives, as can be seen in the difficulty of performing the same kind of processing in Roman times.

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, the processing technology of Lekugu cup and cage cup has not reached a consensus conclusion in the academic community, however, with the advancement of chemical analysis and microscopic imaging technology, more details that have been ignored by predecessors or cannot be discovered due to the limitations of scientific and technological level have gradually surfaced one by one.