Rui/Interview

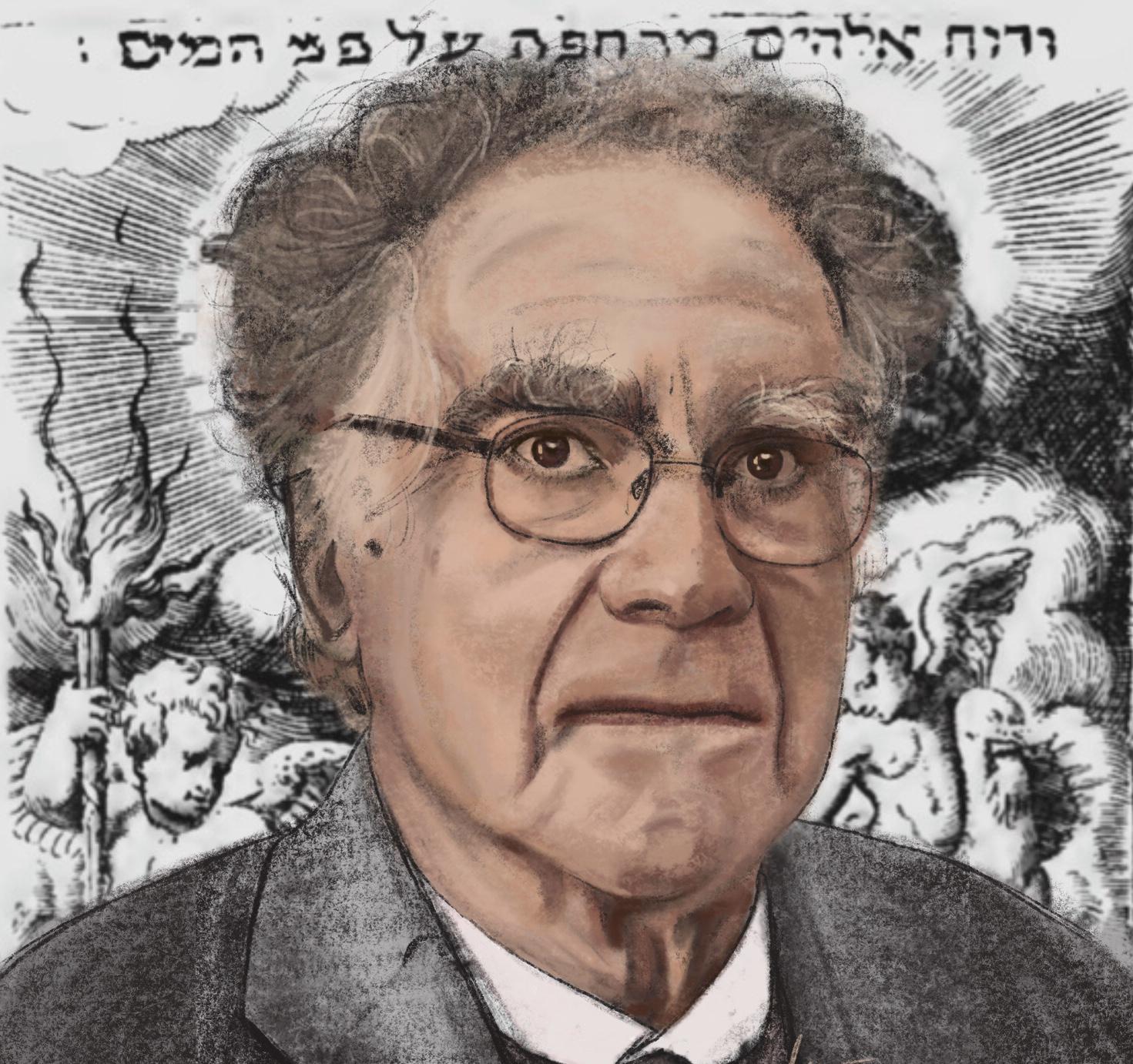

Carlo Günzburg (Zhang Jing)

Born in 1939, the Italian historian Carlo Ginzburg became a figure in the field of microhistory at the age of forty with his books Night Combat: Witchcraft and Agricultural Worship in the 16th and 17th Centuries and Cheese and Maggots: A Universe of a 16th-Century Miller. In addition, his research interests span social, cultural and intellectual history from Renaissance Italy to early modern Europe, and his achievements are internationally renowned in academia. As one of his masterpieces, Cheese and Maggots has been published in more than twenty editions in Italian, English, French, German, Portuguese, Catalan, Spanish, Russian, Japanese, Korean, Czech, Hebrew, Polish, Estonian, Finnish, Croatian and other languages, and is an enduring classic. In July 2021, Guangxi Normal University Press, Ideal Republic, launched the Chinese translation of Cheese and Maggots, the first time in the 45 years since the book was published in the Chinese world. The Shanghai Review of Books commissioned Chinese translator Rui to give an exclusive interview to Carlo Günzburg, asking him to talk about the book's writing and his views on microhistory.

Cheese and Maggots: A 16th-Century Miller's Universe, by Carlo Günzburg, translated by Rui, Guangxi Normal University Press, Republic, July 2021, 400 pages, 75.00 yuan

As a world-renowned historian in his eighties, do you have any questions about the thirty-seven-year-old scholar who spent more than a decade developing "material that could have been just a footnote" into a "best-selling and widely circulated work of microhistory"? Is there a question about this book that you have been preparing or hoping to be asked, or even thought of in your mind for many years, but no one has dared or wanted to ask you?

Carlo GÜNZburg: For years, I've been in the middle of a conversation about who I am today as a historian and the same person I was earlier in my career. I realized almost immediately that the intention of this imaginary conversation was to see myself as a case study: from this point of view, narcissism is a means, not an end. I tried to understand, in the course of my research, my biases, assumptions, and preconceived judgments (why not?). What roles do they play—and to what extent they are corrected or modified by my findings. I was also particularly curious about the role that hidden memories ("cryptomemory," a term Freud used in a letter to a friend) played in the research. In other words, the distance between today's me and the one I was a long time ago was used by me as a means of alienation. As would happen in any historical study, this experiment began with some problems of reverse chronology, which could be revised and corrected based on documentary evidence. In this case, the reader may find that the word "microhistory" is never mentioned at all in Cheese and Maggots, the "best-selling and most widely circulated work of microhistory." Why? The answer is simple: in the late 1970s, microhistory first emerged as a project, stemming from a series of heated discussions among a group of Italian historians associated with the magazine Quaderni storici. These people were Edoardo Grendi, Giovanni Levi, Carlo Poni and myself. One of those hotly debated topics was my 1976 book, Cheese and Maggots. As always, research precedes; labels (including the "micro-history" tag) follow. But the meaning of the word "microhistory" is often misunderstood, mainly on the issue of the prefix "micro" (which derives from the Greek word mikros), because what it refers to— both literally and symbolically — is often interpreted as the object of study. According to this interpretation, microhistory will focus on trivial, marginal issues (as in the case of microhistory in Mexico). But in the case of microhistory that concerns me personally, the prefix "microscopic" is actually a metaphor for the microscope, pointing to a method of analysis of history. You can place a small piece of bee wings under a microscope, or you can put a small piece of elephant skin under a microscope. The protagonist of Cheese and Maggots, Menocchio, is a completely unknown miller; but in the "Microhistory" series, which I was responsible for with my friend Giovanni Levy (another famous microhistory), my first book, Indagini su Piero (the English version of The Enigma of Piero), discusses the fifteenth-century painter Piero della Francesca) is a group of paintings, and he is a great and globally renowned painter (this book published in Italian was first published in 1981 and expanded in 1994, and has been translated into English, French, German, Spanish, Portuguese, Japanese, Russian and Czech). Microhistory analysis can focus on individuals, as well as on communities, events, and other objects. As I said, it emerged as a collective enterprise, and then spread to many countries, in all its forms. My own path into microhistory has been centered on trial cases from the very beginning of my research career. My first book, Night Combat (1966), was translated as Chinese in 2005 and has now been reprinted with a new post-memory. The book is already based on the study of a case. But cases always raise the question of generalization: they also include the extraordinary ones that I particularly like. (I'll stop there, because it's an endless topic.) )

Night Battles: Witchcraft and Agricultural Worship in the 16th and 17th Centuries, by Carlo Günzburg, translated by Zhu Geshu, Guangxi Normal University Press, Republic, June 2021, 352 pp. 65.00 yuan

Cover of the Italian edition of Carlo Günzberg's The Mystery of Piero

From your books and articles, I can see a rush of curiosity to explore the hidden threads hidden in history, literature, and art. Where does this curiosity come from? How do you maintain this curiosity? Sometimes, in the process of collecting information and writing, the initial curiosity will slowly fade, how do you deal with this problem?

Carlo Günzburg: Your observation is absolutely correct. I was particularly fascinated by the initial stages of a study, when I was confronted with a whole new subject—a subject that I often knew nothing about. I once described my feelings at that stage as an euphoria of ignorance. But what is so exciting is the elimination of the possibility of ignorance: learning is possible. I have said that the species to which we belong—Homo sapiens—got its name not from "knowing," but from "knowing how to learn." Over the past few decades, my fascination with the literary genre of essays has intensified, perhaps to significantly increase the excite experience of being exposed to new questions that I know most of the time. Many years ago, on a public occasion, I mentioned a masterpiece by the great Spanish painter Goya, showing a very old man with a long white beard and two canes: the painting was signed "Aún aprendo" (I am still learning). Goya sees himself as the old man, and so do I (si parva licet, "If a dwarf like me were to be compared to a giant like him"). A collection of four essays of mine has just been published in Chile under the title I'm Still Learning.

Cover of Carlo Günzburg's essay collection I'm Still Learning

In your opinion, how do your personal life experiences relate to the fragments of Menocchio's life that you choose to examine and describe in detail, such as the way he reads (chapters 16-42) and his writing style (chapter 45).

Carlo Günzburg: There's no doubt I learned a lot from the way Menorchio reads. Looking back, I think that in the course of the analysis, I was inspired by two books that had a great influence on me: Freud's The Psychopathology of Everyday Life and Ernst Gombrich's Art and Illusion. I realized that there was a gap between Menocchio's recollections of the books he had read and those of fact, and that was part of everyone's daily experience—though not everyone could think at once of a moment to use that divide to recreate a deep interplay between oral culture, peasant culture, and printed books.

Title page of the Italian utopian literature The Great World, published in 1552

When I first entered the profession of journalists, the editor-in-chief of our magazine was Zhu Wei of People's Literature at that time. He once told me that there are many striking similarities between writing and photography, and both need to have a good enough "depth of field": for a good work, the blurred background outlines that we choose to put outside the focus play an equally important, or even more important role, than the clearly recognizable objects in the focus plane. So I'm curious, in the process of researching and writing Cheese and Maggots, are there some interesting facts and details that you found in the course of your research that you consciously omitted or blurred? If the answer is yes, can you tell us about the thinking and trade-off process at that time?

Carlo Günzburg: Good question. The act of writing always means that we may marginalize or abandon certain elements of reality that we should describe. This is true for all descriptive works, from novel to history, despite the obvious differences between them. The Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges wrote a beautiful and witty sketch in which he described a one-to-one map of empire and its subsequent ending. In the case of Menocchio, I was confronted with not a real fragment, but a series of archival documents in which Menocchio's statement was presented through the filter of the Inquisition judge. Inevitably, my analysis focused some elements clearly and others on edges or backgrounds. But here, I tend to make a different comparison, not with photography, but with cinema: after all, all narrative works—including historical narratives—unfold slowly over time. I was deeply influenced by a famous essay on montage techniques by the Soviet film director Sergei Eisenstein. Of course, his cinematic masterpieces also had a deep influence on me. The narrative structure of Cheese and Maggots is interspersed with long or short passages, which can be likened to a montage combination of close-up and long-range shots.

Taking on the previous question, are there any facts and details that you ignored at the time, or clues and traces of abandonment, and now that you look back, you think they should be discussed in the book?

Carlo GÜNZburg: Obviously, it's possible to focus on Monterreale, the town where Menocchio lives— rather than Menocchio himself, and everything else. In principle, there were a variety of other possible options, but in fact I didn't care about them at the time. I don't regret it: that's what this book looks like.

In the opening verse of Cheese and Maggots, you quote a famous quote from Celina: "All interesting things happen in the dark... We know nothing about the true history of humanity. "It sounds very pessimistic. Were you a pessimist at the time? What now? In the decades since then, your book and some other excellent work on historiography have shown that "all things interesting" can be partially revealed to the world, and that we can know a little, if not a great deal, about the "true history of mankind." Have you ever thought of revising the preface? Or add a commentary?

Carlo Günzberg: This statement sounds a bit extreme, but it shouldn't be taken literally. It declares the innovation of this experiment and its hidden richness. It's a challenge. But as I wrote in the last sentence of the book, we know a lot about Menocchio, but we know nothing about the countless human individuals who have not left a trace before and after death. This vast and inevitable disproportionate situation between historical evidence and historical reality should not be forgotten— both historians and readers of historians.

The reason why "Cheese and Maggots" has achieved such great success is not only its originality in historiography, but also the book's distinctive protagonist, Don Quixote-style Menocchio. The cute and delightful sixteenth-century miller you created reminds me of many of the characters I read as a teenager in Calvino's Italian Fairy Tales and Collodi's Pinocchio. In fact, when I translated some chapters of Cheese and Maggots, my writing style drew heavily on the Chinese translations of these two books. However, due to my limited level of Italian, the Chinese translation of Cheese and Maggots can only be based on the English translations of John Tedeschi and Anne Tedeschi. Although I have had a lot of pleasure reading the English translation, and I believe that John Tedeschi, who is himself a good historian, has given a fairly good translation, the problem of "lost in translation" occasionally bothers me. What do you think about this? Have you ever been puzzled that the literary nature of your work may not have been fully appreciated by non-native Italian speakers because of the language barrier?

Carlo Günzburg: I'm glad to hear that in translating Cheese and Maggots, you borrowed from the Chinese translations of Calvino's Italian Fairy Tales and Collodi's Pinocchio. I was lucky enough to be a friend of Italo Calvino (who was not only a first-rate writer, but also an extraordinary person). In an interview published only after his death, Calvino mentioned that Pinocchio was significant to him, a model of compact, concise style. This book is also a model for me. (Incidentally, I think Colody has been of great help to me in distancing herself from the obscure jargon of Italian academic circles, which often has nothing to do with brevity; but in this respect I have also been helped by my mother, Natalie Günzburg, a famous novelist who also likes to write concisely and practices it.) The filters you used in translating my book must have been apt—and it was extremely insightful to think of choosing them. Unfortunately, because I don't understand Chinese, I won't be able to see how something is lost and how something is being added in your translation. This is inevitable. If translations had never existed, human history would have been completely different—and extremely narrow and cramped. This is a "lost and regained" thing. I am deeply grateful to my friends John Tedeschi and Anne Tedeschi, as well as to you, for you have made my book accessible to many ordinary readers who I cannot speak directly to in my native language.

Menocchio's extraordinary personal charisma certainly contributed to the book's success. But if I'm not mistaken, the book was translated into many languages (which I am curious about) thanks to its two core themes: the challenge to political and religious authority, and the interplay of oral and written culture. Both themes easily cross borders and resonate with readers, even though these readers are very different from those I know.

Cover of The Cheese and maggots, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013

As a historian, you are known for your work on the social, cultural, and intellectual history of early modern Europe. You have elaborated in several articles on why history, especially the fragmented, distorted, contradictory history of oppressed and alienated people living in particular places and times, in particular cultures, still makes sense to people in other places and places of time and culture. In fact, reading Menocchio's story and the Protestant Reformation and the spread of the Catholic Counter-Reformation and printing as a backdrop did help me better understand the trajectory of my life. But there is often only a thin line between "learning from the past (or invoking history to criticize or justify reality)" and "abusing history," which is now becoming more and more pervasive. As a scholar who doesn't seem to mind being labeled "radical," "subjective," and "populist," how do you balance the two?

Carlo Günzburg: I will interpret your challenging question in two different, even opposite directions. "Abuse of history" can mean either projecting/imposing the past on the present or an opposite process. What leads to these two trajectories is an impulse to make an analogy between the present and the past: for example, as you point out when you compare your own experience with that of Menorchio, the influence of printing can be compared to the influence of the Internet. These analogies are not only plausible, but also have the potential to yield lucrative results—if they are used as a starting point for reflection, which should also focus on the differences. There is a famous saying that the "past" is a strange country (this is the first sentence of L.P. Hartley's Letter Deliverer [1953], and later quoted by D. Levental in The Past is a Strange Country [1985]), but the "present" is also a strange country (we return to the question of alienation, to the view that in order to better understand reality, we need to see reality as something difficult and strange). In other words, we must learn the languages of those nations; we must learn to translate those languages into our own language (the Latin translation is interpres, which means interpretation).

There is always some kind of competition between old and new memories, and the history shared by each generation is, to some extent, always the product of collective forgetting. As a historian who has successfully salvaged so many old memories and resurrected so many forgotten individuals, would you like to share some of your experiences with young Scholars in China?

Carlo Günzburg: The tension between memory and forgetting mentioned in your question is, of course, crucial: but first we need to clarify two things.

First, memory is not the same as history. All human societies pass on certain memories from one generation to the next; but history, as a form of knowledge, was and is present in only certain societies. Memory can be nourished by anything, including history (in societies where history has existed or is existing as a form of knowledge). However, the experience of memory may be subjectively true, but objectively false; memory can modify the past in every possible way because it does not involve evidence. In contrast, history as a form of knowledge depends on evidence (which may also include memories, and even false memories), which opens up the possibility of pursuing the distinction between true and false based on evidence.

Second, the production of evidence always implies inequalities of all kinds: hierarchical differences in society, hierarchical differences in gender, hierarchical differences in age. The evidence we have about peasants, women, and children in any society is obviously not comparable to the evidence we have about the social elite, men, and adults (vis-à-vis). This inability to compare is not only quantitative, but also qualitative. On this issue, if I am not mistaken, the case of Menocchio, which is analyzed in Cheese and Maggots, may have some educational significance. An alternative interpretation of the inquisition's trial literature to complete the rescue of the voice, thoughts, beliefs, and actions of an unknown miller may provide some enlightenment for those who have embarked on a study of the evidence produced by European colonists around the world (court records, official investigations, etc.) and who are trying to rescue the voices, thoughts, beliefs, and actions of the colonized. But this is just one example. That alternative interpretation strategy can also be applied to literature produced before and after European colonization. One must learn a technique that focuses on the way evidence is produced and the likelihood that something that is recorded in the evidence— often reluctantly, is rescued. For decades, I've been fighting skeptical relativism, the kind of (once?) The popular idea that there is no strict boundary between fictional narratives and historical narratives. But I wrote, "The idea that the source material provides a shortcut to the truth as long as it is reliably sourced is, in my opinion, equally pediatric." The source material is neither the four-wide open window as perceived by positivists, nor the fence that skeptics insist on blocking view: if we really want to make any analogy, we can compare them to a distorted ha-ha mirror" (C. Ginzburg, History, Rhetoric, and Proof, The University Press of New England, Hanover and London, 1999, p.25)。

Neither this process of distortion nor the distorted mirror which this mirror reluctantly presents to us should be analyzed as closely as possible, beginning with the problems that were born in the present. The answer will be unpredictable.

History, Rhetoric, and Proof, by Carlo Günzburg, University of New England Press, 1999

Battle of the Night and Cheese and Maggots make you one of the definitive figures in the field of microhistory. Would you like to compare the differences between you and several other famous micro-historians, such as Leva Radhuri and Natalie Zemun Davis? I'm also curious to see if there have been any trends and findings in this field over the past four decades that you don't want to relate to.

Carlo Günzburg: Natalie was a close friend of mine, an admirable historian, and an extraordinary person. I was struck when I read her Society and Culture in Early Modern France (1975). Later, I wrote an afterword to the Italian edition of Natalie's The Return of Martin Guerre, which was published by us as part of the "Microhistory" (1984) series. I've also met Le Valladduri; he published a very kind book review of the French version of The Night's Battle. It would be interesting to compare Le Valladduri's Montaillou (1975) with mine," Cheese and Maggots (1976): the two books rely on inquisition records from different periods (the former in the Middle Ages; the latter on the early modern period) with different focal points (the former focusing on a village; the latter on a farmer). All of these works use the same method of historical analysis. But that's not the case for many books labeled "microhistory." But labels are irrelevant. As I have often said, a bad work of microhistory is a bad work of history.

Montayou, by Emmanuel Levaadhury, translated by Xu Minglong and Ma Shengli, The Commercial Press, 2011

What are you doing right now?

Carlo Günzburg: I am currently revising a proofreading of a collection of essays, which will be published in Italy in September this year. Two of the essays were unpublished; many had previously been published in English or French; and four had been translated into Chinese. They address a wide range of issues. As Voltaire said, "I love all literary genres, except le genre ennuyeux." I hope readers don't get bothered by me.

In general, do you think you have achieved your academic ambitions in your twenties? Do you have any academic regrets?

Carlo Günzburg: At that time, I never even dreamed that my work would be translated into so many languages, including Chinese. It still seems like I can't believe it. What regrets do I have about my work? I have some near-term plans that I probably can't complete. But I've always been very lucky.

New Historiography, Vol. 18, edited by Chen Heng, Elephant Press, 2017

Note: For the relevant views of Mr. Carlo Günzburg in the first question and answer of this article, see "Making It Strange: A Prehistory of a Literary Setting Technique" (translated by Li Gen), "Our Words and Their Words: Reflections on the Skills of Historians" (translated by Li Gen), "Microhistory: Two or Three Things I Know" (translated by Li Yingxue) in The New Historiography of New Historiography published by Elephant Press in 2017, "Making It Strange: A History of a Literary Setting Technique" (translated by Li Gen), and "Microhistory: Two or Three Things I Know" (translated by Li Yingxue).

Editor-in-Charge: Shanshan Peng

Proofreader: Yan Zhang