<h1 class="pgc-h-arrow-right" data-track="2">

</h1>

<h1 class="pgc-h-arrow-right" data-track="8" > (5) Reality is both ubiquitous and inaccessible: trust yourself in the theater?</h1>

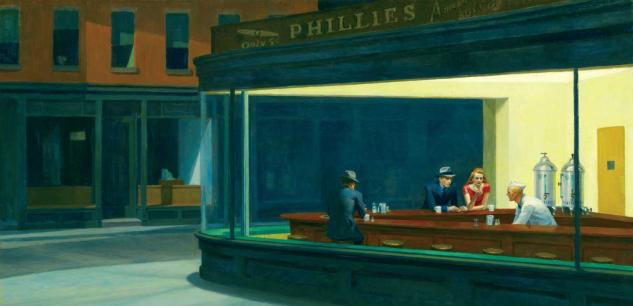

Edward Hope (1882-1967) Nighthawk, aka The Night Wanderer, oil on canvas, 84.1 cm× 152.4 cm. Art Institute of Chicago

The bar reception extends beyond the screen. Walking on the sidewalk, the footsteps at work are loud and unnatural. The town is so clean that it looks like a movie set, and the streets look like they're in an abandoned town built up in a Hollywood studio.

This is Greenwich Avenue in New York. The Phillies bar is also true. Hope may have come here often when he lived nearby. The author only paints the main structure, the shell of reality, but he adds enough realistic details to make us believe in the painting. We do have doubts and wonder to ourselves: Is this really the corner of Manhattan? Or was it remade with cards? The painter only relies on some things of daily life, and they are all related to the figures in the painting. They may be props that actors need to flesh out their characters: cash registers in the opposite store, round stools in bars, some cups, and cigarettes. Nothing complicated, just to establish the character of the character and make the scene more realistic.

Nighthawk, aka The Wandering Man (1942)

We walk by and imagine ourselves in a movie, a black-and-white movie with colors added later. The conversations are very short, that is, exchanging a few words, and the head does not have to be lifted. The man across from us, elbowed on the counter, spoke like Humphrey Bogart. In the heavy shadow of his hat, his eyes were fixed somewhere in front of him. The woman who had smeared heavy eyeshadow was looking at her nails. How much do they know about each other? Maybe they've just met and there's no need to talk. Besides, what else can they say? The bartender was looking for something under the counter, dealing with a few words. He had seen these things before, and there was much more to it than that.

Hope's paintings are full of smoothness and smoothness, as if his brushes never encountered any obstacles between the movements. Everything is in order, including silence and bright colors. The surface of the painting is textureless, full of indifference, and does not feel any change. There is nothing unexpected, which makes the viewer's eyes wander, and our eyes will wander between color blocks. Hope's characters are not interested in us or the outside world, and the man sitting in the bar with his back to us clearly shows this. He was in a corner of his own, content to sit alone on a round stool, occupying the longer side of the bar, keeping a certain distance from other drinkers.

The Phyllis Bar was open all night, its windows shining a dazzling light that illuminated the opposite floor, trying to invade the inside of the store, casting a triangular light on the wall inside one of the windows, but this light still avoided everything it touched. In many early paintings, the moving natural light and the brightness of the lamp would accompany our train of thought, suggesting the passage of time, allowing us to observe closer to the painting, but it was also a challenge for the artist, who had to grasp the shining light and the nuances it caused. In contrast to this tradition, Hope succeeded in capturing the purely functional indifference of the electric light source, which was reflected in the outline line of the building. This light has no feelings, pours down, is unchanged, and is in place, like the light of a dentist's office, illuminating the surface of the skin miserably white.

The bar's interior bathes the streets in green, while smudging the entire painting: sidewalks, shops and its empty windows, and even shutters, which are kept open by the heat of the apartments on the block. The composition and cropping of the picture prevented us from seeing the place above the window on the first floor, and made the atmosphere of the picture heavier. The sky is far above and completely invisible. Pale pictures do not allow anything to pass through, not a trace of wind.

We may have the illusion that if we stay too long in front of this painting — in front of this building — something will happen — a sneaky shadow appears in a window, another passerby appears, or something happens in a bar.

But no, the painting is still desperately monotonous, nothing out of the ordinary. It seems that everything is so simple, so simple. And we will never venture outside of this apparent world. Hope's paintings have a trap-like effect, creating anticipation in the viewer and inviting us to imagine that since such a void exists, something will fill it. He provided scenes and characters, but never gave plot. It was as if he had arranged for himself a meeting that he knew he would never attend. It is in this that the value of the painting is hidden: as soon as we begin to think that the image is a deception and more boring than it seems, we clearly understand the constitutive characteristics of Hope's art. His true subject matter transcends anything purely descriptive in order to express a sense of disillusionment that occupies the viewer. We also enter into silence, which drowns out the others in the harsh light of the bar; the only substitute for the darkness of the street is the glare of the light. Under the lights, men walking in the streets at night look even more lonely. Phyllis Bar is really not much to see. Or, if there were, it would be another kind of emptiness.

What if we try to get in? But you may have missed the entrance and can't find it now. In this slow-motion image, Hope succeeds in enticing us deeper. We often feel tired at night, and the painting takes advantage of this. We need to trace our own footsteps and find the door. Where will it be? It's not worth the effort, it's too late, or next time.

Reference Information

It is said that Hope's painting was inspired by the short story written by Ernest Hemingway, "The Killers". The story, first published in 1927, is about two hired gunmen who are waiting for their target in a restaurant, but the man does not show up that night. A dozen pages of story, the overall atmosphere is more important than the plot, creating a sense of fate and indifference. The door to Henry's dining room opened and two men came in. They sat at the bar..." "I couldn't help but think that he was waiting in the house, knowing he was going to be killed. Too bad. "Hey," said George, "you'd better not think that way. ”

The silhouettes of the male figures in the painting are based on Hope himself, but it is difficult to say that they are self-portraits. Hope's wife, Josephine Nevison, acted as a model for the women in the paintings, as did many of Hope's other works.

Hope is a big fan of theaters. "When I'm not in the mood to paint," he once said, "I'll go to the cinema for a week or more." "Hope's aesthetic embodies the Hollywood world in many ways: lens-like installations, contrasts of light, perspective, all of which are reminiscent of moving cameras, the smooth texture of cinema film and the geometric use of space. Even so, there is little direct evidence that Hope has any paintings that point directly to a movie. However, his images often influenced the film industry, and films often borrowed from the straight-line decorations in his paintings, because they were easy to manipulate, and they could also produce a sense of emptiness, and it was easy to create a dramatic tension.

The most famous example is Hitchcock's 1960 Psychopath. It recreates the house in Hope's 1925 work The Railway. The most recent response to Hope has been david Lynch (blue velvet, Twin Peaks, and The Story of Mr. Street) and Wim Wenders, who referenced the nighthawk to the painting in The End of Violence.

Hope's approach to realism is straightforward, a broader trend in the history of ideas, with sources dating back to the origins of American art. American painting, which originated in the Dutch Protestant tradition in the 17th century, still shows its love of everyday life and its desire to show the authentic and believable side of society two centuries later, so it pays great attention to detail. The emphasis on practical observation and the rush to directly represent the visible world transcend relatively abstract considerations in art and are ultimately embodied in secularized art. As a result, the more sophisticated the painting, the closer it is to objective reality, without too much dramatic plot or obvious expression of feelings. The development of such an attitude to the extreme will inevitably accumulate the effect of wrong vision painting, which is also one of the pursuits of American painters in the 19th century. Hope avoids illusion-inducing artistic techniques and instead adopts a relatively isolated approach to realism, that is, he is not just a person who paints in a pictorial way. His narrative does not deceive the observer, he lists things, but does not play with us: for him reality is both omnipresent and inaccessible.