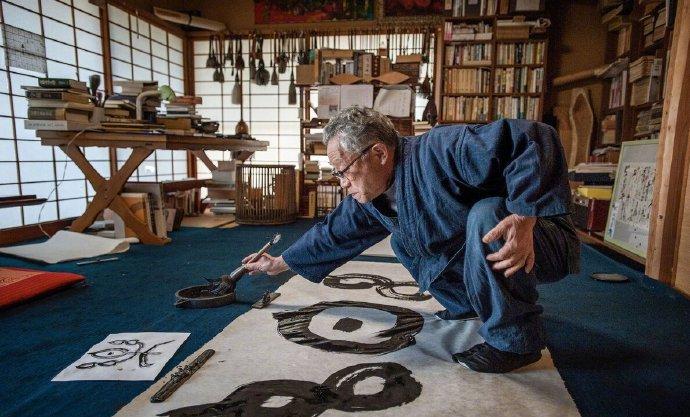

Calligraphy master Kawamata Masamune is writing on paper. In some parts of Japan, people are still handcrafting this traditional paper. Photo by JAMES WHITLOW DELANO

Written by: ROB GOSS

Every summer, giant samurai "walk" through Aomori Prefecture, Japan. These awe-inspiring paper mountain bikes are at the heart of the Aomori Sleeping Demon Festival. The evening celebration will take place in August and last for a week, making it one of the largest seasonal events in Japan.

The roller coaster depicts kabuki and Japanese mythological scenes, next to taiko drummers and dancers. Hikari maker Hireo Takenami tells us that it takes months to design and build each roller coaster, and the Aomori Sleeping Devil Festival is 300 years old, and for most of the time, the roller coaster is only covered with washi paper , a kind of paper made by hand from a tree.

Takenami admits that today's roller coasters are not all traditional. "During the parade, we had waster that was destroyed by a sudden downpour, so I used non-handmade paper that contained some synthetic fibers that were rainproof," he said. But it is not pure washi paper. ”

This fine-tuning of tradition is understandable, and has become increasingly common as machine paper has largely replaced washi paper across the country. But in many towns, the arduous handmade papermaking continues. In 2014, UNESCO listed washi paper made in three counties as intangible cultural heritage.

"It's important that these technologies don't disappear in the future," Says Takeshi Kano, "and it's vital to nurture the next generation of artisans and impart knowledge at the right time, which can lead to an industry that revitalizes the economy." "Thanks to the efforts of craftsmen such as Kano, the traditional way has been continued.

Washi origins

According to the Nihon Shoki, a Japanese chronicle written in 720 AD, paper was introduced to Japan by three Korean monks in early 600 AD. Gradually, Buddhism took root throughout Japan, and paper was originally used to copy scriptures.

Over time, people began to use trees to make improved versions of paper with stronger fibers, which increased durability, and washi paper was widely used. Tough, absorbent washi is ideal for calligraphy and other ink-related forms of artistic expression.

Due to the way the filter is filtered, coupled with the strength produced by the winding fibers, washi paper is used to make door and window paste paper, as well as lanterns and lamps. During the Meiji era (1868-1912), Japan began to modernize and westernize, and before that, the paper used everywhere was Japanese paper.

Washi paper is not only versatile, but also environmentally friendly. Unlike industrial paper, washi paper is made with only new branches and does not require the entire tree to be cut down. Conventional papermaking tends to use chemicals, while manual paper is not the case and is biodegradable.

However, as Japan developed into a modern industrial country, washi paper was replaced by other kinds of paper; mass-produced paper was more cost-effective. For example, most mesh doors today use mechanical paper.

Approaching washi paper

Japan's most legendary was the Mino Washi: Every October at the Mino Washi Lantern Art Exhibition, a lantern is lit up in a commercial district that existed since the Edo period. From elementary school students to highly skilled artists, these lanterns are made in a variety of ways, but they are all made from local Mino washi paper. For more than a thousand years, the region has produced various grades of washi paper, collectively known as "Mino Washi paper".

Takeshi Kano is one of eight Mino craftsmen qualified to make "Ben Mino Paper". Ben Mino paper is the purest and most traditional Mino washi paper, accounting for about 10% of Mino's total papermaking. To qualify, papermakers must train for at least ten years with a member of the Benmei nono Paper Conservation Society.

In 2014, Motomino paper was listed as an Intangible Cultural Heritage by UNESCO, along with ishishu half-paper from Hamada City, Shimane Prefecture, and Hosokawa paper from Ogawa Town/Higashi Chichibu Village, Saitama Prefecture. In evaluating these areas, UNESCO wrote: "People living in these areas are proud of their washi-making traditions and regard them as a symbol of their cultural identity. ”

"[This title] has nothing to do with washi, with the maker, it confers on the craft of making washi paper," Kano says, "for example, Ben mino paper must be made entirely by hand, using only three raw materials: tree, water, and yellow marshmallow, and the marshmallow mucus ensures that the paper fibers are evenly distributed." ”

Like Motomigno paper, Ishizu Half Paper and Hosokawa Paper are made entirely by hand, using only trees. Over the years, they have had similar uses, but is unique in that they are used as masks for local Iwami Kagura dancers. It is a theatrical dance derived from Shinto rituals. Other types of washi, such as non-Ben Mino paper from Mino Prefecture, use trees, three-sycamore bark, or shrubs called "goose skins", plus dyes to form different colors.

Washi, which is classified as an intangible cultural heritage, is not easy to make, and craftsmen have been following traditional craftsmanship for centuries. First, the tree is steamed until the bark is soft enough to peel off. The inner bark is rinsed clean, a step that is usually done in the cold water of a river or stream, then dried in the sun, naturally bleaching.

The bleached bark is boiled in an alkaline solution to remove the gum that holds the bark fibers together. The papermaker then begins the arduous chiritori (塵取り) process: the fibers are placed in cold water, and the papermaker carefully picks out spots and dust.

Papermakers then soften the fibers by hand and mix them with water and goose skins into large vats to form pulp; dip into the pulp with a bamboo curtain frame called "truss" to form a sheet of pulp; then use bamboo mats to scoop up the pulp and shake it evenly; and finally remove the pieces of paper, press them overnight with heavy objects, and dry them on wooden boards. From pulp to paper, it can take up to several weeks.

Wonderful washi paper

In Mino City's Historic District of Houses (named after the firewall that stands out between the buildings), visitors can experience the contemporary and traditional uses of handmade washi paper at the craft shop, including making clothes, handbags, paper umbrellas, interior decorations, and business cards. Last year, Japanese textile maker Takebe even introduced reusable masks made from washi paper.

Ishikawa Mino and Paper Crafts Workshop is located in the Kukenebo Historic District, where visitors can make various crafts such as washi dolls. At the Mino Washi Museum, visitors can also experience the washima-making process with the help of small bamboo curtain frames. For a deeper look, the washi tour organized by Mino Washi-nary is not to be missed, with visitors visiting tree-making plantations, artisan workshops and manufacturing plants.

In Echizen Paper Village, Fukui Prefecture, there are about 60 Wataru paper manufacturing plants, some of which are completely handmade and others that use modern technology. Every Year in May, the local shrine holds a three-day celebration in honor of the goddess of paper. Throughout the year, visitors can build a paper craft museum to make washi with local craftsmen or visit a factory. In Tokyo, 17th-century paper wholesaler Ozu Waka also had experience in making washi, and there are handmade paper from all over Japan.

Today, Washi is no longer the only paper in Japan, but it is still alive and well, and it has even been integrated into the Olympic Games. This summer, if the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games, which have been postponed due to the epidemic, can be held smoothly, the top eight of each event will receive honorary certificates printed on Ben mino paper.

(Translator: Sky4)