Almost any European or American who has taken a lesson in Chinese history is familiar with the following quotation, which is a passage from the Qianlong Emperor's Edict to King George III when he led a British delegation to China in 1793:

The Heavenly Dynasty has four seas, but it is not valuable to make great efforts to govern and handle government affairs. This time, the king of Er entered all the things, remembered his sincere dedication, and specially instructed the steward to store them. In fact, the Heavenly Dynasty is far away, the kings of all nations, all kinds of valuable things, ladder voyages, everything. Erzhi zhengshi and so on. However, it is never expensive and coincidental, and there is no greater need for state-made objects.

Since the 1920s, the above passage has been widely quoted by historians, international relations scholars, journalists, and teachers to illustrate traditional China's loss of awareness of rising Western powers: the Qianlong Emperor foolishly believed that George III was paying tribute to him, while his disparagement of British gifts was seen as a rejection of Western science and even the Industrial Revolution; traditional Chinese foreign relations, linked to tribute and embodied in prostrations, stood in stark contrast to equal diplomacy among emerging European nations. Implicit in this conclusion is a broad interpretation of the political culture of the Qing Dynasty, which has been criticized by experts for many years. However, how did the traditional interpretation of the quotation in the previous paragraph come to be? And what makes it enduring?

Extensive reading of Qing history archives shows that the widely quoted passage does not represent Qianlong's true reaction to the British mission, which Qianlong mainly regards as a security threat; rather, a large number of sources show the British concern for etiquette in the 18th century, and the influence of this concern on Chinese and Western scholars when the Qianlong Edict began to be widely circulated in the early 20th century. An examination of how the Edict of The Qianlong Emperor, King George III, was interpreted shows that both the editorial choices of historical archives and our views on Qing history today are still influenced to some extent by the political changes in China in the early 20th century.

Criticism of the use of a passage from Qianlong's edict to characterize pre-modern Chinese diplomatic relations has been around for years. This criticism focuses on two types of research: first, the study of the influence of Western science on the Qing court; second, the study of the Qing Dynasty as a Manchu conqueror dynasty. Scholars who study the history of Jesuit priests in China have long pointed out that the Qing court was very interested in Western astronomy and mathematics. The Kangxi Emperor studied Euclid's Principles of Geometry and other mathematical writings under the guidance of Jesuit priests, while his grandson, the Qianlong Emperor, collected a large collection of European-made clocks, automatons, and astronomical instruments. In her influential essay "China and Western Technology in the Late Eighteenth Century," Joanna Waley Cohen examines the early Qing emperor's interest in European military technology provided by Jesuit priests, and Cohen argues that Qianlong was motivated by domestic political considerations. It is only in the above quotation that China's cultural superiority and self-sufficiency are emphasized. There are also some scholars who have studied Manchu and Central Asian language literature and argue that although the Qing emperors used Confucian institutions and philosophies to govern their Han subjects, they did not impose these ideas on the frontier peoples of their empire, but rather constructed the relationship between the Qing court and them according to the cultural systems and ideas of the frontier peoples. Laura Newby argues that the Qing dynasty followed the same principle in its foreign relations with Central Asia and did not always adopt the Confucian concept of a tributary system for those regions. More recently, Matthew Mosca added that Qing officials in the 18th century had realized that they were part of the global trading system, and knowing that Britain and Russia were important players, the Qing Dynasty insisted on one-stop trade because the qing dynasty's initial institutional structure gave local officials such as the Governor of Liangguang, the Governor of Guangdong, and the Guangdong Customs Inspectorate over diplomacy.

Although the above research challenges traditional interpretations, the perception of Macartney's visit to China as we know it has a profound impact. In the 1990s research by James Hevia and Alain Peyrefitte, culture and etiquette were placed at the center of explaining how the Qing emperors reacted to Britain, although in other respects they were completely different in methods and arguments. Moreover, the quotation from the Edict of King George III of the Qianlong Emperor remains a familiar way for the public to understand China. Students in middle schools and universities continue to analyze it, and journalists continue to cite it; it is also used by current scholars of international relations as a historical illustration of the international community's current thinking, the idea of China-centered Asian diplomacy, which is the basis for a new interpretation of international relations in Asia today.

First, where does the influence of relevant interpretations come from

The reason why the above quotation is very influential is mainly due to the fact that it is the original text of an important diplomatic document of the emperor. Over the years, however, there have been repeated calls for a critical look at the political process of how historical documents were brought before historians. This starts with the fact that some scholars are currently studying topics that are different from those who have written and compiled archives before them. Social historians look for the lives of silent groups in order to uncover potential messages that differ from superficial writings from reading historical documents. Further reflection gave rise to Ann Laura Stoler's view that archival compilation had both the power to document politics and shape politics. In this regard, Kirsten Weld examines in particular the ability of institutions that write archives to oppress people (and hide that oppression) to discourage those seeking rehabilitation. The study of how archival materials are used not only helps us to understand those who are silent, but is also valuable for the study of politics and diplomacy, especially the need to reconstruct past history in order to legitimize the present after a major political transition.

After the Xinhai Revolution, the Qing court archives were no longer used as a collection of essays to provide information on the decisions of the imperial court and to praise the emperor, but were used as a source of information to explain the rationality of the demise of the Qing Dynasty. Crucial to this process is the work of a group of Chinese scholars. They published the Palm Chronicle in the 1920s, and the political situation at the time influenced their selection of materials on the history of the Visit of the Macartney Mission to China, which became authoritative historical materials. In particular, in compiling archival materials on the Visit of the Macartney Mission to China, this group of scholars focused on documents that showed the Qing court's concern for rituals and rituals, while ignoring those about the Qing court's military response to the British threat, and these historical texts were disseminated to Western readers through Fairbank's research. Fairbank wanted to use Chinese archives to balance the popular views of Westerners on China's diplomatic history at the time, but his emphasis on Chinese archives also meant that his research would be heavily influenced by the selection of archival materials, and the archival materials he came into contact with were screened by the Chinese scholars who managed the Qing history archives at that time and made public to historians.

Terry Cook called on historians to seriously consider the role of archivists as cocreators of history, as archivists could decide which archives to keep and which to exclude. As far as the case of the Macartney mission's visit to China is concerned, the "Case of the British Envoy Macartney's Appointment" published by the Republican archivist in the 1920s was not replaced by the richer "Compilation of The Archives of the British Envoy Macartney's Visit to China" until the 1990s. These Chinese archivists of the early 20th century were all influential intellectuals, and the vast amount of existing materials and research also makes it possible to study their attitudes and actions in the process of compiling archival materials. A careful study of the historical documents on the Macartney Mission in the two sets of archival materials, the Compilation of the Archives of the British Envoy's Visit to China, not only enables us to transform the British Mission's visit to China from a well-known story of etiquette disputes into a story of the Qing court's military response to the British threat, but also enables us to see the important force of data selection in the process of archival editing; this force shapes the history we tell ourselves and others.

Second, what is the truth?

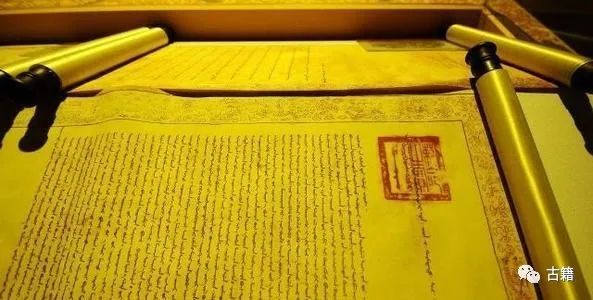

Surprisingly, the popular interpretation of the Edict of the Qianlong Emperor to King George III shows little resemblance to the reaction of the Qing court at that time, as can be seen in the Compilation of Archival Historical Materials of the Visit of the British Envoy Macartney to China, published in 1996 by the First Historical Archives in Beijing. Since the Qing historical archives are far from being completely preserved, the Compilation of Historical Materials of the British Envoy Macartney's Visit to China does not include all the archives at that time, nor does it include all the documents related to the study of the Macartney Mission, but only selects materials related to the mission. Nevertheless, the Compilation of Archival Historical Materials of the British Envoy Macartney's Visit to China collected more than 600 relevant documents, including the Edict of the Qianlong Emperor to King George III containing the above quotations, and the letters from the Qianlong Emperor thanking the British for the gift of the beep gowns. The Compilation of Archival Historical Materials of the Visit of the British Envoy Macartney to China is compiled in its entirety, but there is a convenient catalogue that can be consulted in chronological order.

If we read the Compilation of Archival Historical Materials of the Visit of the British Envoy Macartney to China in chronological order, the story begins with a letter: a letter from the British East India Company to the Governor of Liangguang in October 1792 informing the English King that he intended to send a mission to congratulate the Qianlong Emperor on his birthday. This was followed by numerous correspondences between the imperial court and officials as officials from China's coastal provinces waited for the British ships to appear. In late July 1793, the mission arrived in Tianjin, where the members of the mission took a boat to Beijing, then crossed the Great Wall and traveled to the Chengde Mountain Resort to meet the Qianlong Emperor, and there was a lot of official correspondence between the Qianlong Emperor and his officials. Most of these official documents were about the itinerary, and there was also a lot of discussion about the gifts brought by the British: asking the British to provide a list of gifts, and the methods of transporting, assembling, and displaying gifts, and some of them were discussions of the etiquette of the mission when they visited the Qianlong Emperor, and only a few documents mentioned the issue of prostration, and several of them blamed Zheng Rui for being arrogant and arrogant, and fantasizing that the ambassador should kowtow to him.

The turning point took place at the end of September 1793, when two major events occurred. First, after the mission returned to Beijing from Chengde, Qing officials began to arrange their southward journey to Guangzhou; second, a series of British demands were translated into Chinese. When the Qianlong Emperor read these requests, he felt very unhappy. The British not only wanted to remain permanent ambassador in Beijing (in order to bypass the Governor of Liangguang and the Guangdong Customs Supervision), but also wanted to trade with Beijing in coastal ports, demanding tax breaks, while demanding an island in the Zhoushan Archipelago near the port of Ningbo and a base near Guangzhou. These demands had significant political and financial implications, and the emperor certainly soon realized this. Thus the formulaic edict that had been written earlier to the King of England was thrown away, and a new edict was drafted according to the Emperor's personal instructions. The newly drafted edict states and rejects all requests made by the mission article by article. Although many readers believe that Macartney was rejected because of his refusal to kowtow, which led to the anger of the Qianlong Emperor, the edict does not mention kowtowing or any other etiquette issues, but focuses on the statement and rejection of the various demands of the mission. This edict is the source of the famous quotation from which it preceded. In that quotation, Qianlong downplayed British gifts on the one hand; on the other hand, emphasized his own generosity. The edict was officially handed over to Macartney, and the mission left Beijing in a hurry.

Since then, in the large number of surviving documents, its main concern has been on how to avoid the possible military consequences of rejecting British demands. Just before the mission left Beijing, the Military Aircraft Department issued an important edict to the governors of the coastal provinces. In his edict, the Qianlong Emperor issued an edict to the governors of the provinces, and warned: "England is stronger among the Western countries, and now it has not failed to do what it wants or caused a slight disturbance." He went on to urge the governors to strengthen their defenses and instructed canton officials not to give the British any excuse for military action.

Now that the country wants to allocate trade to the coastal areas, then the sea frontier generation of camp news, do not specially rectify the military appearance, and it is advisable to prepare for precautions. That is, islands such as Ningbo's Pearl Mountain and nearby Macau islands should be in phase with the situation, and the first thing is to be taken care of, and it is not allowed to be occupied by the English Yi people. ...... The Guangdong Customs' collection of Yishang Tax was originally to be levied in accordance with the regulations. English merchant ships come to Guangdong more than other countries, and in the future, it will be inconvenient for the country's cargo ships to enter and leave, and their taxes will not be reduced, and they will not be allowed to levi anything, so that the country's merchants and so on can be excused.

This edict was followed by a repertoire of local officials reporting on their actions in accordance with their orders, and much of it was about how to get rid of the five British warships moored in Zhoushan at the time, especially the heavily armed "Lion". Zhoushan Island has a deep-water port, which is one of the reasons why the British want to establish a base there. Macartney once explained that because many sailors were sick, they needed to rest on the island. This was also true, as there was a severe dysentery outbreak aboard the Lion, which resulted in the deaths of many people. The Qianlong Emperor accepted their request to rest on the island, but at the same time urged local officials to let the British ships leave as soon as possible. Captain Ernest Gower recorded in his logbook that they had been deported by Chinese ships while sailing south along the Chinese coast, and that locals had thrown dirt into their wells, leaving them without clean water. They show their power by firing their guns, and Chinese ships docked in the harbor also show their strength from time to time. Others were to report to the emperor on how they had demonstrated military might to the British missions that were sailing south (these also appeared in the Records of the British, which mentioned the large number of soldiers patrolling along the way and made dismissive comments about the cannons displayed by the Qing soldiers. )

Mixed with these edicts of the Qianlong Emperor, there was a series of recitals written by Song Jun and Ai Xinjue Luo Changlin, who was responsible for the reception of the mission, and Chang Lin accompanied the mission to Guangzhou, taking over the post of governor of Liangguang and at the same time taking over the escort work of the mission in Zhejiang. Their task was to negotiate trade with the mission, on the one hand to dispel the idea of causing trouble for the mission, and on the other hand not to make any concessions to the demands made by the British. From the song played by Song Yun and Chang Lin to the Qianlong Emperor and from Ma Garni's report to the British Minister of the Interior Henry Dundas, it can be seen that Song Yun and Chang Lin were very successful. The general impression of the archives is that in the minds of the Qianlong Emperor, an effective military and diplomatic response to British demands was far more important than the prostrations and other ceremonial issues discussed before the Macartney mission arrived in Beijing.

Throughout the 19th century, the Chinese account of the Macartney Mission also presented a similar narrative. The Qianlong Dynasty in the Records of the Qing Dynasty was compiled mainly from foreign dynasty literature, which lacked some military details that could be found in the emperor's private edicts to his ministers. Nevertheless, the editorial staff's compilation of the historical materials of the Macartney mission's visit to China was relatively fair, including the "Edict of the Qianlong Emperor to King George III" and the Emperor's edict on military action. Until the 1930s, Qing Shilu was only open to a very small number of readers; some works published in the context of the Opium War also emphasized British territorial claims and the military response of the Qing Dynasty. The Guangdong Haiphong Compendium (1838) contains the official edicts of the Qianlong Emperor to the English King, as well as a tougher edict written by the Qianlong Emperor to his officials in response to British demands, as well as his edicts on how Songjun and Changlin should respond militarily and commercially. In addition, the Guangdong Customs Chronicle (1839) contains another harsh edict of Qianlong, emphasizing the importance of not allowing the British to occupy the islands, and ending with an edict establishing coastal defense. The same theme appeared in the Qing Dynasty's History of Foreign Relations, published in the 1890s, placing the Visit of the Macartney Mission in the context of a powerful dynasty that defeated the Ghurkhas and successfully negotiated borders with Russia. In all the Qing dynasty literature, the Macartney mission was seen as a defense issue, with a focus on military preparations and the management of trade in Guangdong by the British.

Third, where is the source of the so-called "etiquette dispute" concern?

Since the Qing court saw the Macartney mission as a military threat from Britain, how did the popular view of "ceremonial disputes" come to be? To understand this question, we must first look at the British literature of the time. The Qianlong Emperor seemed to be well aware of the etiquette to be used for foreign envoys, and was more flexible, at least he did not ask his officials to carry out a full set of prostration ceremonies when they had some kind of informal visit to the envoys at the Chengde Mountain Resort, far from the capital, outside the Great Wall. Europe, by contrast, was in the midst of a historical context in which relations between the rulers of the world were undergoing dramatic changes, and diplomatic etiquette was at the heart of negotiations on how those relations should change.

Scholars who study early modern European history point out that although the Peace of Westphalia of 1648 is often considered to be a sign of the beginning of equal diplomacy for sovereign states, in fact, the concept of sovereignty developed gradually, and until the 18th century, the old court hierarchy system still existed. As D.B. Horn commented in his brilliant study of British diplomacy: "The importance of etiquette in the 18th century (of diplomats) seems too much for writers today." He pointed out that the European powers of this period would not accept ambassadors from other countries unless the country's national power status was comparable to its. He also detailed the cases in which it was difficult for different countries to send ambassadors between countries due to issues of etiquette and privilege. One example is that the Habsburgs, as rulers of the Holy Roman Empire, refused to confer the title of "Majesty" on the King of England because he was only a King and not an Emperor. This made it difficult for britain at the time to send ambassadors to Vienna. The "American Revolution" and the "French Revolution" exacerbated this problem, as the powerful new state they created was a republican system, traditionally the lowest-ranking entity in the court hierarchy. The "American Revolution" and the "French Revolution" also brought the Enlightenment idea of "equality" to a political prominence; previously, it was primarily directed at the individual, and now it begins to extend from the individual to the state. However, even in the 1790s, this idea was still controversial. After the return of the Macartney mission, Thomas James Mathias published a poem in which he claimed to be a translation of a passage from the Edict of the Qianlong Emperor george III, in which the Qianlong Emperor denounced the leader of the French Revolution:

Above the world of shock!

The banner of evil equality is unfurled,

The blood flowing filled the air,

The words on the flag: freedom of fraternity, death, despair!

Mathias was a member of the Queen's chamberlain and a satirist. His anonymous attacks on literary celebrities of the time, as well as on French intellectual circles, were widely welcomed by conservatives. As the poem implies, equality is far from universally accepted, even as an ideal. It was not until the "Congress of Vienna" in 1816 that the etiquette of equality between nations was accepted. Even so, this ideal, like the ideal of China's tributary system, has not been put into practice.

In the context of hierarchical diplomacy, which is still a recognized diplomatic relationship in Europe, it is not surprising that britain, before the mission left London, had begun to pay attention to the etiquette of the Chinese emperor's visit to the british royal mission. In his letter to Dundas, Macartney had anticipated the possibility of encountering "kneeling, prostrating, and other boring Eastern rituals" and said he would be flexible in dealing with them. In James Gillray's famous cartoon The Reception of the Diplomatique and His Suite at the Court of Pekin, the British bow down before a reclining Oriental monarch, which is often used to illustrate the importance of kowtowing to China's Reception of the Macartney Mission. In fact, however, the painting was published long before the mission left London. The painting represents not China's concern for etiquette, but the British public's concern about the posture of British diplomats, and has become a core criterion for judging the success of the mission. Macartney often mentioned etiquette, especially the question of prostration, in his diary, which expressed his anxiety and was clearly intended to record how careful he was in dealing with the problem. John Barrow of the Macartney Mission wrote an influential book about the Mission, which emphasized Macartney's refusal to kowtow, claiming that in fact Chinese was too rigid in matters of etiquette. In this regard, Laurence Williams believes that Barrow's formulation reflects the influence of British satire on the description of the mission by later generations, and they hope to subvert satirical criticism through defensive descriptions.

This preoccupation with etiquette continued to appear in 19th-century English writings on the Macartney Mission, as diplomatic etiquette remained a concern of the European powers in China at the time. Westerners valued the form of etiquette they used to do business with China, and their diplomats refused to act according to Qing etiquette, saying they were not representatives of tributary states. The Qing court, on the other hand, oscillated between—or refusing to receive the reception altogether unless the members of the mission accepted the prostration ceremony—or adopting an alternative ritual that avoided formal reception. In 1816, the British sent a delegation led by Lord Amherst to China, and the Qing court refused to receive them unless the members of the mission accepted the prostration ceremony; but on several occasions in the late Qing Dynasty, the imperial court adopted an informal ceremony to avoid formal receptions— and the British therefore did not have to kowtow. In Britain, the political importance of the issue of etiquette continued to ferment, as evidenced by James Bromley Eames's influential general history book The English in China, published in 1909; a book that criticized Macartney's arbitrariness in prostrating himself and, in the author's preface, dedicated the book to a British officer in the Eight-Power Coalition. The American William Woodville Rockhill published an article on prostration in the newly founded American Historical Review in 1897 entitled "Diplomatic Missions to China: The Kowtow Problem," and in 1900 he was appointed U.S. plenipotentiary to the "Executive Committee on Reforming Qing Diplomatic Etiquette." It can be said that until the Xinhai Revolution, the issue of etiquette during the Visit of the Macartney Mission to China was the focus of Western attention, while Chinese literature emphasized the British threat and the military measures taken to deal with this threat.

At that time, the Edict of the Qianlong Emperor george III was not widely known. The English translation of the edict has long been forgotten in the archives of the British East India Company, and even the tireless Hosea Ballou Morse did not mention it in his 1910 history of foreign relations of the Chinese Empire. The original of the edict can be found in documents on the defense of The Cantonese Customs, but it was not until 1884 that the "Continuation of Donghua" was written and attracted attention. In 1896, Edward Harper Parker translated into English the Qianlong Edict extracted from the Records of The Continuation of Donghua. Parker's interest at the time was to use these new sources to study the Gurkha Wars of the 1790s, and although he published a translation of the Qianlong Edict in a London magazine, it did not arouse any particular repercussions.

What led to the fame of the Qianlong Emperor's Edict to King George III was the demise of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 and the rise of nationalism. In 1914, two British writers in China included the English translation of the Qianlong Edict into their history of the Qing Dynasty. It was from this English work that Chinese scholars selected the Edict of the Qianlong Emperor. For them, Qianlong's ignorance and complacency in the edict coincided with the Republic of China Revolution. The Qianlong Edict is one of the famous documents that appeared widely and popular in the study of Qing history before and after the Xinhai Revolution. The other is The Ten Diaries of Yangzhou, a book that depicts the brutality of the Qing conquest in the 17th century and has also been translated into different languages for publication. The fact is that the archival documents of Qing history obtained by historians through the same procedure make the explanation of the revolution particularly effective and lasting.

For British writers, the failure of the Macartney Mission gave legitimacy to the existence of British power in China. For this purpose, Macartney's demands were summed up as diplomatic relations and free trade (rather than tax breaks and claims for territorial bases). Morse put it: "The Act of Moderate Trade Rights, introduced by England in 1793, was realized by force in 1842. "British writers begin with the visit of the Macartney Mission to Huawei to tell the story of Sino-British relations, by telling the story of britain's two attempts to achieve legitimate and equal relations between countries through diplomatic means, but both unfortunately failed, and then justify the British use of force against China, while avoiding the substantive demands of the mission in writing. One effect of this was to make the Qing dynasty look more like a reaction to a clash of cultures.

Shortly after the 1911 Xinhai Revolution, Sir Edmund Backhouse and John Otway Percy Bland published a book on the history of the Qing Dynasty, including a complete translation of the Edict of the Qianlong Emperor george III. This is a witty and interesting bestseller. The book presented the Qianlong Edict to the public, and some people used it as evidence of Chinese arrogance, thus defending the British invasion of China. However, Brand and Sir Bakerhouse themselves were inclined to romantic conservatism, and they regarded the Qianlong Edict as evidence of the qianlong emperor's greatness, in stark contrast to China's later decline: "How rapid and thorough has the process of the decline and humiliation of this great heavenly empire since its rulers portrayed themselves as 'the heavenly dynasty has four seas'. After that, the Edict of the Qianlong Emperor george III was quickly well known to Western readers. Out of confidence in the Superiority of the West's own culture, Westerners often ridicule the rhetoric in qianlong's edicts.

The philosopher Bertrand Russell, who had lectured on a lecture tour in China, had read the works of Bland and Backhouse, and in his own 1922 book, The Question of China, he excerpted a long passage from the Qianlong Edict and then commented: "No one can understand China unless the absurdity of the edict no longer appears." Arnold Toynbee also quoted the Qianlong Edict in the 1930s, arguing that "the best cure for this insanity is ridicule" (although he believed that there was a completely similar attitude in the West at the time). Toynbee, like Bland, saw a pungent taunt in the contrast between China's arrogance in the 18th century and the decay of the present. Readers and authors coincide in their satire of the Qianlong Edict, and some authors try to find the root causes of some of China's practical problems from the language of the Qianlong Edict, which is undoubtedly part of the reason why the quotation in the Edict has endured in Western literature. Previously, the most expressed view was that the Qing Dynasty had a vast territory and a strong territory under the rule of the Qianlong Emperor.

Brand and Bakerhouse's work also catered to the complex sentiments of conservatism, national pride, and republicanism mixed with many Chinese elites, so much so that Brand and Beckhouse's work was translated into Chinese within a year of publication. Combining the story of the fall and corruption of the Qing Dynasty with the critique of the Qing Dynasty by china's Westernized elite, which constituted China's new political authority, the Chinese translation of the book was a sensation when it was published, and was reprinted four times between 1915 and 1931. For Liu Bannong, a Chinese reader, however, there is little to be ridiculed for the Qianlong Emperor's grandiose remarks, which are in keeping with Chinese tradition, and are derived from well-known classical sources and Chinese diplomatic practices, and are merely incorporated into the book's general textual description of the romance and tragedy of the Qing Dynasty in the past. Inspired by the writings of Brand and Bakerhouse, Liu Bannon decided to translate the diary of Macartney, which had just been published at the time. In the preface, both Liu Bannong's Ma Jiaerni and the Qianlong Emperor show impressive flexibility in the negotiations, and are a model for China's future handling of foreign relations. However, Liu Bannong's fresh view of the Macartney mission, while welcome, was considered unscholar. Translators who translated Brand and Bakerhouse's work into Chinese felt it was their duty to point out how unreliable Liu's views were, because Liu was a novelist, not a historian.

It was through the popularity of these words that the English literature on the Macartney Mission caught the attention of Chinese historians and archivists. In 1924, the remnants of the Qing Dynasty were expelled from the Forbidden City, and the Palace Museum was established. Subsequently, the archives of the Military Aircraft Department, which had been taken over by the State Council, were transferred to the Palace Museum. At the same time, the Palace Museum also took over the remaining case files in the Forbidden City, including the originals of provincial officials. Today, the popular perception of the events of the Macartney Mission is only part of the grand project of reshaping the history of the Qing Dynasty in the past, which was based on how to obtain and compile archives, but the reshaping of the contents of the Qing historical archives was hidden under the story of the struggle to rescue and sort out historical materials.

Before the fall of the Qing Dynasty, many documents had been lost due to poor maintenance and space savings, coupled with the destruction of two foreign armies. Later, the government of the Republic of China, which came to power after the Xinhai Revolution, destroyed some archives that Republic of China officials deemed useless. The decision not to retain some documents, while frustrating to historians, is an indispensable part of the management of national archives. By the 1920s, in addition to political transitions, Rankean historiography influenced Chinese studying abroad. They began to use archival research as a Western method of scientific research. This method coincides with the tradition of the original Qing Dynasty examination of evidence. So when scholars found bags of Qing Dynasty archives sold as waste paper in the Beijing market, they reported the terrible thing in the press, which once again made the archives academically (and financially) valued.

However, the rescue of Qing archives is only part of a larger, politically motivated project to use them to find the truth about Modern Chinese history. In other words, to create a new history that criticizes the Qing Dynasty. Two senior scholars, historians Chen Yuan and Shen Jianshi, were assigned to the archives department of the Palace Museum. Shen Jianshi is a well-known scholar who is still known for his work as an archivist. The two invited Xu Baoyu, who had served in the Qing and Republic of China governments, to manage the archives. These people all experienced the Xinhai Revolution and were all members of the Republic of China government. Chen Yuan, a member of the Chinese League, entered the National Assembly after the Xinhai Revolution and held a series of government positions in the Beijing government. He was also an outstanding expert in the study of the history of early foreigners living in China and was employed by the Institute of Sinology of Peking University. In addition, he is a member of the newly established Institute of History and Literature of the Chinese Academy of Sciences under the leadership of Shen Jianshi. Xu Baoyu was an official, and he and Chen Yuan were active in the same social circle, and they were both members of the "Thinking Mistake Society". The society meets twice a month to edit text and discuss scholarship. Another member of the society was the historian Meng Sen, who became famous for his research on how the Yongzheng Emperor came to power through conspiracy, one of the qing dynasty's greatest scandals. Shan Shiyuan, as Xu Baosu's assistant, excerpted and transcribed many documents, and he was a student of Meng Sen. The personal backgrounds of these new archivists and their circles will almost inevitably lead them to favor historical documents that help to revise the history of the Qing Dynasty.

He made his first visit to the archives in December 1927. Like other visitors to the archives, Xu had the idea of discovering secrets. He found a box that read, "Yongzheng gave an edict in a certain year, and he must not open it before the Holy Emperor, and those who violate it will do the Fa-rectification." Xu Baoxun then opened the box and found that it contained many small document bags, which were about the case of accusing Chinese literati of anti-Manchu writing. He decided to select materials from these archives for publication. A few days later, he discovered a batch of edicts written by the Kangxi Emperor to a eunuch in Beijing when he was traveling from Beijing. These edicts were "like the family letters of ordinary people's families", which made Xu Baoyu extremely excited. He decided to place the encyclicals at the beginning of the new volume of his writings.

In the following months, under the guidance of Chen Yuan and Shen Jianshi, Xu Baoyun and his assistants compiled the first volume of the Palm Ancestor Series. The volume contains 47 documents on the visit of the Macartney mission to China, which until the publication of the Compilation of Archival Historical Materials of the British Envoy's Visit to China in the 1990s, which was the main source of Chinese information on the visit of the Macartney mission to China. John Launcelot Cranmer Byng translated some of these documents into English and published them under the title "Official Chinese Documents of lord Macartney's Mission to Beijing in 1793." Kranmer Beiger considers these documents to be "very complete records" of the Macartney Mission's visit to China, but in fact they are only a small fraction of the more than 600 relevant documents in the archives, which were selected by the original structure of the archives, the preconceived position of the compilers, and the political context of the time.

Similar to other archivists in the period of political transition, Chen Yuan and Shen Jianshi faced the same situation, that is, the bureaucracy that originally created the archives led to their dilemmas in the collation of archival materials. They chose Xu because he had worked in the Cabinet and the Military Aircraft Division, hoping that his internal knowledge would give him a better understanding of the structure of the archives. However, the vast archives and Xu Baosu's limited experience limited them. Many documents of the military response to the Macartney mission are stored in the palace archives, including the qianlong emperor's secret folds. However, none of the palace archives were made public, because these defense issues were both important and confidential, and were not part of the Qing diplomacy that could be publicly displayed, as were the case with etiquette and ceremonial issues. The Military Aircraft Department was the most powerful state agency in the late Qing Dynasty, where Xu Baoyu worked. He believed that the archives of the Military Aircraft Division were very important and had been handed over to the Government of the Republic of China. Therefore, the first to be declassified was the archives of the Military Aircraft Department, not the Zhu Batch folds in the palace archives.

The choice of what literature to publish is also influenced by political factors. At a basic level, the editors' overall view of Qing history was influenced by the nationalist anti-Manchu ideology of that generation. At that time, most of the practical work of selecting and compiling archives was undertaken by graduate students. Shen Jianshi, who instructed these graduate students, wrote bluntly that documents such as the fall of the Ming Dynasty and the literal prison case were very important, and other documents could be used as data and statistics. Another, more direct political context is that in early 1928, when the first volume of the Compilation of the Palm Of the Ancestors was being compiled, Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist army was in the midst of the Northern Expedition, which brought a dangerous situation to the Palace Museum. On the one hand, the conservatives in the Beiyang government expelled the emperor from the Forbidden City and made it a museum deeply dissatisfied: Sun Yat-sen's supporter, The Cantonese Chen Yuan, was arrested during the Beiyang government's suppression of the main kuomintang supporters; on the other hand, the museum was threatened by radicals within the Kuomintang. During the Northern Expedition, the Kuomintang passed a motion to sell the entire palace and its contents as the assets of the rebels. In this context, it is inevitable that the editors of the Series will have to consider how their work can be made more acceptable to the new Government. The new government, seeing itself not only as Sun Yat-sen's successor and revolutionary overthrowing the Qing Dynasty, but also as an anti-imperialist force, was beginning to take back the concession from the British.

It was in this political environment that the first volume of the Palm Series was born. The selection of documents is a combination of the revolutionary nationalism of the compilers and the anti-imperialist emphasis of the Kuomintang in its treatment of Qing history. The first volume begins with photographs of the Kangxi Emperor and the edicts written to eunuchs in Beijing by Kangxi, who had excited Xu Baoyu, when he left Beijing, which will give the reader the feeling that these archival materials can take off the mask of the Qing court and peek into its true face from the inside. Photographs and Zhu Edicts are followed by relevant materials on the Macartney Mission, the rest are the Emperor's Edicts related to the Han nationalist anti-Manchu case (the relevant edicts requiring Han Chinese to wear pigtails in the 17th century) and documents related to the defense of the Chinese border (in which a famous Han general Nian Qianyao fought in Tibet but was executed in a power struggle after the Yongzheng Emperor ascended the throne), as well as documents about the Qing Dynasty's control over Chinese ideology and culture, and the implementation of "word prisons". Although the volume was not a state-directed pamphlet, it was the product of the position of the compilers and the circumstances of the time. These documents originally came from the Qing Dynasty's own records, and the documents themselves did not have a clear hostility to the Qing Dynasty, but when these documents were put together, they contributed to the anti-Qing public opinion at that time. The prominence of these themes in the Compilation of the Palm Series and other archival materials of the time deeply influenced the research of scholars at home and abroad in the following years.

Editors had the same consideration in selecting archival materials relating to the Macartney Mission. In a brief introduction, Xu explained that the Visit of the Macartney Mission to China was the beginning of China's international relations, and that his purpose was to provide new historical materials that were not found in the Records of the Continuation of Donghua. Archival documents begin with Francis Baring's announcement of the establishment of the embassy and end with the departure of the Macartney mission from Beijing, and a large number of documents cover the period when the mission rushed to Beijing and later received a visit in Chengde; its effect was to highlight the period during which gifts and etiquette were discussed, thus omitting all archival documents related to military reactions, and pushing this narrative effect to a climax through the Edict of the Qianlong Emperor George III. This effect was partly due to the use of military aircraft office archives, which dealt with trips from Tianjin to Beijing, as well as the arrangement of the missions' residences in Beijing and Chengde, while the correspondence between the emperor and Songjun and Changlin, as well as the provincial officials responsible for coastal defense, was largely preserved in the palace. Despite the Qianlong Emperor's Edict to King George III.

In addition, Xu Baosuan also selected three of the eight documents on the prostration ceremony to publish. This practice of highlighting the prostration problem is obviously directly influenced by the long-term emphasis on etiquette and ritual in British scholarship, when in fact the prostration issue is not so important in the entire archival material. Hsu's diary records that he visited Koo Hung Ming, a Chinese Malaysian who had been educated in England, in order to get a translation of a Bahraini letter. Perhaps at the suggestion of Gu Hongming, Xu baosuan then purchased the Chinese translation of the Diary of Macartney and the Japanese Inaba Kunzan's The Complete History of the Qing Dynasty (1914). The Diary of Macartney mentions the issue of etiquette several times, while Inaba Junshan's work places the mission in the framework of the debate over equal diplomatic etiquette, and ends with the Edict of the Qianlong Emperor George III.

Overall, the selected archival documents in the Palm Chronicle have the effect that the Qing Dynasty is portrayed as an ignorant and passive dynasty in the face of rising Western powers. Qing officials showed undue attention to the details of etiquette on the one hand, and unaware of the military threats they faced. One of the debates here is, what led to the weakness of the Qing dynasty's military power in the 19th century? This debate is consistent with the early 20th-century critique of Confucian culture, its relevance to the May Fourth Movement, and the broader interest in using cultural differences to explain the disparity in power between China and the West in modern times. Both sides call for further Westernization, and the historical study of Sinicization by scholars such as Chen Yuan is part of the political resonance of the debate. Some aspects of the above critique have convinced many scholars to this day; just as many archival compilations deliberately excluded certain archives in their compilation, the problem with the Compilation of the Palms is that the influence of various historical and political factors in its compilation was not reflected in the final publication. After a few introductions, the Palm Chronicle does not give any hints about the number of archival documents it has eliminated, leading the reader to think that they are immersed in the original voices of 18th-century Qing officials who have not been embellished. And Qianlong's edicts ordering military responses to provincial officials were in the archives of the Military Aircraft Department, and both documents were published at the time, but Xu Baosu chose to end with the Edict of the Qianlong Emperor and King George III, rather than with the edict of the Emperor ordering the provincial officials to respond militarily in the following days.

How did the voice of Chinese scholars reach the West?

The archival materials on the history of the Macartney Mission in the Compilation of the Palm Of the Ancestors were again transmitted to the West through Fairbank. Fairbank emphasized the use of Chinese archival materials and passed on this style of research to his graduate students, who later became scholars of American-led Chinese studies. Fairbank regarded the Macartney mission, especially the Edict of the Qianlong Emperor George III, as a symbol of the conflict between equal diplomatic relations in the West and China's concept of world domination, and considered this conflict to be the driving force behind the development of China's modern history. By using archival materials that were being published at the time, he appeared to be justifying his views with the true thoughts of Qing officials. However, the archival materials he came into contact with were actually selected by the compilers of Chinese historical materials, and the results were naturally misleading.

Fairbank studied under Ma Shi, a prominent British archival researcher, but decided to pursue a career in Chinese archival research. In 1935, he traveled to Beijing to collect information. As an American graduate student with limited Chinese and little connections in China, he had little access to the palace museum's senior archivists. Through Jiang Tingdian, Fairbank came into contact with the archives mentioned above. Jiang is a few years older than Fairbank, speaks fluent English and completed his doctoral dissertation on British Labour Foreign Policy at Columbia University. At that time, Jiang Tingdi was the head of the history department at Tsinghua University, and he was also politically active, and was a member of the new Kuomintang government. In the 1950s, Jiang served as the Republic of China's representative to the United Nations, perhaps his most well-known role. At that time, he had just completed an influential archival compilation of books, Compendium of Materials on the Diplomatic History of Modern China, 1932-1934.

In his analysis of China's modern history, Jiang combines his generation's obsession with cultural differences between China and the West with the English-language claim that European countries are pursuing the ideal of equality between nations. He pointed out that China's relations with foreign nationalities in the north have long existed, but that is not a diplomatic relationship. However, he was also skeptical that european countries' motivation for handling diplomatic relations was the pursuit of equality between states. In his 1938 investigative article on China's modern history, he wrote ironically: "The relationship between China and the West is special: before the Opium War, we refused to give equal treatment to foreign countries; in the future, they refused to give us equal treatment." When the Sino-Japanese War broke out, he wrote with great sorrow that there was only one important question: "Can Chinese be modernized?" Can you catch up with the Westerners? Can science and machinery be harnessed? Can we abolish our sense of family and hometown and organize a modern nation-state? ”

Fairbank was directly involved in the construction of Chiang's tributary system, and together with S.Y. Teng published a series of articles on Qing archives between 1939 and 1941. Deng Siyu conducted a detailed study of the Great Qing Huidian (大清会典), a work that covers a number of topics such as summarizing diplomatic concepts and diplomatic etiquette from diplomatic practice. Relying on Deng Siyu's research, Fairbank and Deng Siyu proposed that the tributary system was mainly to solve trade problems, and in this system etiquette was more important than strength. Unlike Jiang Tingdi, they agree with the Western view of pursuing equal diplomacy between countries, believing that this is a cultural feature of the West. But like Mr. Jiang, Fairbank is using these topics to illustrate the question of whether China can modernize. A few years later, shortly after the Chinese Communist Party took power, Fairbank argued: "China seems to be less able to adapt to the modern living environment than any other mature non-Western country." Fairbank considered modern life to be incompatible with Chinese tradition, including nationalism, industrialization, the scientific method, the rule of law, entrepreneurship, and invention; but his own research focused primarily on the issue of China's diplomatic relations and placed it within the framework of the tributary system.

These views on China's diplomatic relations were more widely disseminated among English-language readers because of the great success of Fairbank and Deng Siyu's 1954 textbook book, China's Response to the West. It is an edited information book that combines "selected and condensed for the greatest possible meaning" with a strongly implicit textual narrative. The outline of the book was originally written by Deng Siyu according to the general framework of the works on the history of the Chinese revolution, beginning with the anti-Manchu nationalism of the early Qing Dynasty and ending with the victory of the CCP revolution. However, this plan was later canceled by Fairbank and replaced with "Problems and Background" as the first part of the book. However, the question that plagued Chiang Tingdi and Fairbank's generation remains: can China modernize? Fairbank re-elaborated on the issue so that the part of how the Communist Party came to power could be included.

Fairbank answered this question within the framework of the transition from a traditional tributary system to a modern system of international relations, using the tensions that arose during the transition as a driving force for other changes. The first chapter ends with the Edict of the Qianlong Emperor George III, but the edict was severely reduced, and all the words in it about the main requirements of the British mission were deleted, and "although it was never expensive and coincidental, there was no more need for the state to make things" became the last sentence of the edict. Then, Fairbank added a paragraph of his own words to make the effect more prominent. He said: "According to this statement, the English and Scottish who were about to break through the gates of the city and destroy the ancient superiority of the Middle Empire were still regarded as uneducated People outside the realm of civilization. Deng Siyu had originally intended to publish the Qianlong Edict along with several other documents on the Macartney Mission in the Compilation of the Palm Of the Ancients, but Fairbank reduced these materials to only one edict and used the edict as one of the most famous examples of the Qing court's inclusion of Western countries in its "traditional and untimely tributary framework."

When the cold war had just begun, the book China's Response to the West began, addressed an important political issue. As Fairbank put it, the rise of Communist power in China is one of the most frightening events in "the entire history of American foreign policy in Asia," and therefore "every intelligent American must strive to understand the significance of this event." He then came up with a solution——— which was to understand history. Fairbank wrote in the book's introduction that if we did not understand China's modern history, then "our foreign policy is blind, and our own subjective assumptions may lead us to disaster." In his depiction of the Qing Dynasty's demise because its officials did not understand foreign cultures, Fairbank was also reminding the United States that if Americans were not committed to understanding China, something could happen. As one commentator wrote, "China is not the only nation suffering because their leaders are unwilling to accept unpleasant facts." But there is no doubt that they have paid a heavy price for this, and we should all be warned from it. So, the book is both a critique of U.S. foreign policy and a call to strengthen research in this area, a view that was shared by many university faculty in the decades that followed.

China's Response to the West has since become a textbook for generations of undergraduate students in the United States and Britain, and is not only still in use today, but will continue to influence future compilations. The use of the Qianlong Emperor's Edict to King George III as the basis for the defense of the United States' foreign policy toward China is as He Weiya pointed out: it is used to represent The culturalism, isolationism, and self-sufficiency of China in the 1960s. Throughout the Cold War, entire generations of textbooks used the quotation from qianlong's edict to illustrate the isolation of traditional China from the rest of the world (this is not convincing to me, because it was the large amount of trade that prompted the Macartney mission to visit China). From here, the Edict of George III is quoted in textbooks of world history and international relations over the past two decades to help readers understand China's current attitude toward Southeast Asia. It is only here that for the first time, the above introduction is no longer mentioned as a joke: China's rise means that international relations scholars will be prepared to look at the Qianlong Emperor's statement in their own way. A new generation of scholars, aiming to challenge much of the Eurocentric scholarship in the field of international relations with the events of the Macartney Mission, pointed out that until recently modern times, non-Western countries were often formulating norms for diplomatic relations, and it was difficult not to sympathize with such research. However, such an approach makes it extremely easy for them to return to the perspective of European egalitarianism and Chinese hierarchism in international relations. This perspective arose from the tensions of the transition to equal ceremonial relations between European countries, and it was written into Chinese history by Chinese scholars to accuse the Qing dynasty, which was overthrown by them, of not being able to distinguish between etiquette and reality.

Fifth, what conclusions can we draw from the whole story

So what conclusions can we draw from the whole story of how the Macartney mission was interpreted? On the one hand, we are seeing the cautionary tale that historians are familiar with: the historical context of interpreting archival documents is important, and quoting a paragraph in isolation is potentially misleading; but furthermore, we need to pay attention to how archives are made available to historians, which will affect how historians use them. In an era of massive electronic digitization of archival materials, a story about the publication of archival materials may seem insignificant; however, in a large-scale data-based archival material, when certain archives are selected and certain archives are excluded without the knowledge of the user, this means that the problem will become more serious when researchers read in search of certain words.

As we begin to examine the problem of omitting archives in the compilation of archival materials, we see that while the Qianlong Emperor replied to the King's letter within the formal framework of the Qing Dynasty's specific concept of world domination, he was also taking action to counter the military threat posed by the Macartney Mission while avoiding potential economic losses. He rightly sensed that appeasing Macartney with vague promises of future trade talks would avoid immediate trouble, but he remained vigilant at all times. Although the Qing court had extremely limited knowledge of the details of British overseas expansion, the Qianlong Emperor and his ministers were clearly intelligent and capable politicians. In addition to reading direct information about the mission, we should also remember that the framework we use today to interpret the history of the Qing Dynasty was formed in the early 20th century, reflecting the concerns of the time, and that this framework created the archives that are presented to us. Whether these frameworks reflect Chinese or Western views on Chinese history remains controversial to this day.

In fact, as we have seen, there has been a lot of communication between English writing scholars and Chinese writing scholars. A more important issue that we need to understand is that the political context of the early 20th century introduced the particular problems of that era. "Can Chinese modernize?" It was a central issue in the study of Chinese and Western scholars at the time, and the Edict of the Qianlong Emperor George III was used to raise the question of whether China "could accept equal diplomatic relations, science and industrialization." Today, such questions seem clearly outdated, and China's growing power on the world stage is pushing for a new round of rewriting of the history of the Qing Dynasty.

About the author: Henrietta Harriso is a professor at the University of Oxford. About the translator: Zhang Li, Professor, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Beihang University, yang Yang, Ph.D. candidate, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Beihang University.

Source: Global History Review, Vol. 20. Transferred from the "Global History Center of Capital Normal University" WeChat public account.