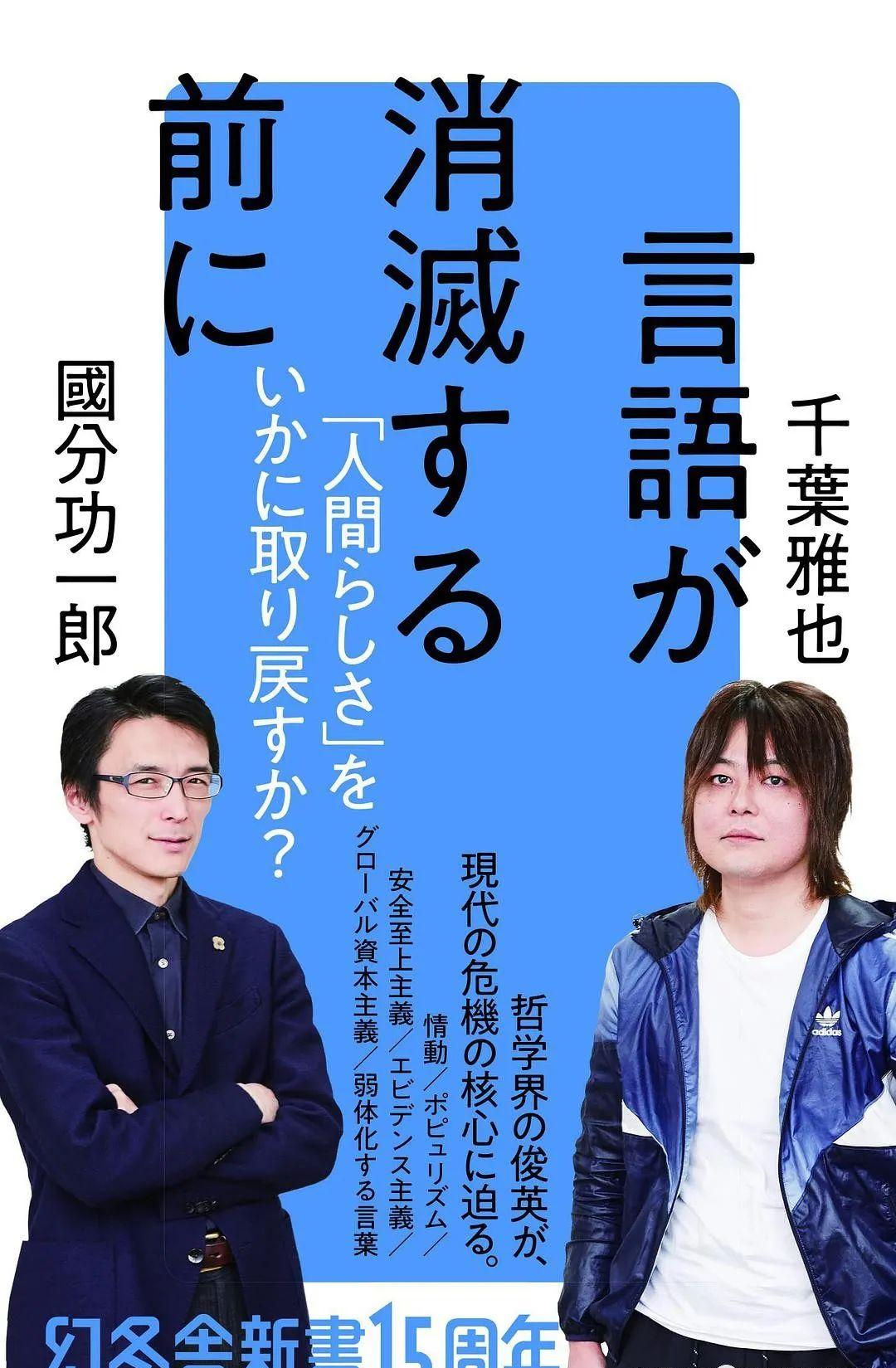

Hara: Before Language Disappears

Original authors: Koichiro Kunita and Masaya Chiba

Translation Proofreading And Typesetting: Chunqi Meikong

Note: Japanese "speech" and "speech", this article is translated as "language", in terms of subdivision, "speech" has more words = word meaning, but in the various contexts of use in this article, it is not easy to translate in this way, simply "language". Both authors have studied Deleuze, and although the word "emotion" = affect is the casual and basically medium research they use, it can be understood as "the movement of emotion" and "moving"; but it should also have the color of Deleuze's philosophy (emotion is the encounter of things that are not themselves... At their own discretion, the translator did not change much.

Small talk: There are no more translations of this book, and the end is sprinkled with flowers. Like please go to Japan to support this book Oh.

For learning purposes only, commercial use is prohibited, and translations are published based on CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Aspirants are welcome to join or contribute private messages (translations or originals): [email protected]

The first release of the network Zhe Neighbor Department, roof authorized reprint

Kokubun is really handsome, and Chiba was also handsome when he was younger

Masaya Chiba (born: December 14, 1978) in Utsunomiya City, Tochigi Prefecture. Japanese philosopher and novelist.

His major is philosophy and representational culture. He holds a Ph.D. (Academic) (The University of Tokyo, 2012). He belongs to ritsumeikan University Graduate School of Advanced Sciences and the Kinugasa Research Organization Institute for Survival Studies. The position is a professor.

[Chiba also won the 162nd Naoki Prize, so it's no problem to be a novelist]

Koichiro Kokubun (born July 1, 1974) is a Japanese philosopher.

Associate Professor of the University of Tokyo. His final degree was in Academics (The University of Tokyo, 2009). He holds overseas degrees in DEA philosophy (2001, University of Paris 10) and DEA and Linguistics (2002, Institute of Advanced Social Sciences).

Humans are becoming less language-free

Kokubun: If I say something exaggerated, doesn't that have something to do with the question of the status given to languages in the modern world? The philosopher Forrest Gumpen pointed out this in his book The Use of the Body, and we are no longer a being prescribed by language.

In fact, Argamben's language seems to negate my writings (laughs), but it is indeed a very important analysis.

Chiba: Well, Kunibi Sang wants to resist the current situation (as Agammoto said).

Kokubun: That's what it says. As I said at the beginning, the twentieth-century philosophy we studied was the philosophy of language. This is why Heidegger tried to grasp existence itself in language. But I think that at the very foundation of such a philosophy of language, there is the premise that human beings are defined by language. In a sense, language is even a prison for us, and that's why we have the idea of how to get out of it.

However, it suddenly occurred to me that human beings were no longer prescribed by language. Language is becoming less prescribed to us. I wonder if this can be pointed out in many places.

For example, this may be a tedious example, but LINE's memes and emoji have a lot to think about. What does that mean?' Even communication without language is sufficient. It's just some kind of emotional/emotional transmission. In everyday communication, this is enough – it is clear.

When writing emails\messages, everyone thinks that they are weaving language and writing articles, but in fact, they are just choosing the options that come out of the input method intelligent prediction. Moreover, this can also be enough to write an article.

In our intellectual circles, we often talk about the "materiality of language". Language itself is some kind of substance, so reading something is like touching a blocky rock. For example, like Hölderlin's poems, which Heidegger was keen to discuss, or what people call the ultimate language of a flash of inspiration in the mind.

But isn't the consensus as a material language disappearing in modern times?

Chiba: Language has become a mere prop. As long as it is used, the language itself becomes a completely transparent means and will not be involved by it (引っかかる). Therefore, it does not matter if it is replaced by emoji, it is also okay to replace it with symbols. Language should be kept as a reason for language, no. In short, communication is becoming more comprehensive. To put it very contrary, language was not something that existed only for communication.

Language itself is something that can be fiddled with\changed, for example, it can be turned into poetry. Poetry is self-purposeful and does not exist for communication. But nowadays (もはや), it is almost impossible to write poetry in a self-purpose manner, and only a small number of good people are still doing it. Everything is dominated by communication, and all means become interchangeable and transformable.

Kokusai: English education is also the same. What an exchange, what an exchange. “HI! HOW ARE YOU? "This kind of thing that can be remembered in a minute or so is taught like a desperate effort."

Chiba: Even so, I dare to speak English and understand the Tao.

Kokubun: There is a lot to say about this situation from the perspective of "diligent study (強いて勉める)", but in short, society is dominated by such things as communication and language is being eliminated – this is a big tendency\ trend, and I think it is necessary to point it out. This tendency can be discussed from a slightly difficult philosophical point of view, or from the LINE level just mentioned.

Chiba: Compared to Twitter, Instagram is becoming more dominant, and that's it.

Language as props, language as matter

Kokubun: I would like to ask Chiba you guy. I myself am a person who can't read poetry – I've always had this, some kind of feeling of inferiority. I think it's not just me, but there are a lot of people in my generation (after XX) who share it.

The language was dead, turned into rubble, and from there only barren fragments were picked up. Because it was already fragmented and there were no rich words, I had to work hard to sort out the order and write in as orderly as possible. That's what I got when I wrote the book. I feel like my language is very poor.

That's why in Japan in the 1970s there was a "Please buy a copy of my poetry!" "That kind of culture, everyone is touched by poetry, right?

Chiba: In Japan in the 1960s, poets had a very high cultural status, and when they said "アマタイ", they had the power of idols.

Kokubun: I'm talking about Tenzawa. But how many people now know about Tenzawa Rejiro? Last time, when I talked to Mr. Genichiro Takahashi, as soon as I said, "I don't read poetry," he said that it is true that their own poetry experience is probably completely different from the generations of the Kokubu people. Generations like Takahashi's, when they want to publish poetry, everyone jumps up with excitement.

However, as a reference for Mr. Takahashi, there was still criticism of poetry in Japan at that time. Although everyone is reading poetry, it is still not clear if there is no criticism. Poets also have critics, and poets criticize each other, so that readers can put them together and read them. I was relieved to hear that I didn't just read poetry at that time.

Qianye Jun, there are still many speeches about poetry.

Chiba: I'll write it myself.

Kokubun: The reading experience of poetry, or the experience of poetry — what is it like?

Senka: Words and deeds. For this reason, the association or disunity—the unfaithy of the 这种说对, 诗啊, and disapproval intentions. This is a sedging. Poetry doesn't understand the meaning. It's an object\object. )

My expressive activities were originally based on art production, so I think that the so-called language is basically an object. It was plain and straightforward thinking. So I'm not good at using language to convey meaning as efficiently as possible. For me, the material configuration of the text, how black the Chinese characters look when you suddenly see a web page, such a dimensional thing often comes to mind at the very beginning.

When I write, I am connected to this compromise between dimension and meaning, so I can't give up using language as a prop. Always fiddling with language as something rough and hard. That's also my weakness, not when I speak, but when I write, I write very slowly anyway, because the materiality of language stumbles on my feet.

Kokubun: Higashi Hiroki said on Twitter that I was able to grasp an article recently because I was able to write with a typewriter (ブロック, section\block, etc.), and I was exactly like this. Grasp the article with sections or paragraphs. Rather than reading sentence by sentence, it is more of a block view, and if the shape of which piece is not right, go to the content.

Chiba: Eh, interesting.

Kokubun: The next plate of a plate is such a size - it seems that there is a mistake in the structural level of the building, which is the judgment. Qianye Jun said that the eyes will first pay attention to the material configuration of language, and I think it is a little closer to this feeling.

In my book "The World of Medium Dynamics", in order to make it easier to read, line breaks and loose plates were added. However, when I look at the picture, there is a lot of black and so on on this page, and I understand that feeling. I feel a little too much black or something. However, although I probably made this judgment (reflection) once, after that, the pressure on how to convey it became stronger, and (I am not sure whether it is the meaning of the article\ the transmission of meaning) became stronger, and (I am not sure myself) whether the article was revised from the above perspective.

When I listened to it just now, I thought, Qianye Jun, I don't talk much about novels.

Chiba: Novels, I'm not good at it. In other words, because of the troubles and disputes between people, the behavior will happen in chains - this kind of thing is too stupid and stupid to do. Because ah, there are troubles \ disputes between people and people, very stupid = baga bar. Because it is stupid, there will be trouble. If all people's souls had risen one step, trouble wouldn't have happened, stories wouldn't have been necessary. That is to say, all novels are foolish, because they are written on the premise of the low rank of the soul. So, I don't feel the need to read novels.

Kokubun: A very radical proposition suddenly appears here (laughs).

Chiba: But there is no one in the poem. Only matter. So that's great.

Kokubun: That's the way it is. That's what you mean. Then again, my books are always said to feel like speculative fiction. This is especially true in deleuze's Philosophical Principles (Iwanami Shoten, 2013). What Jun Chiba said is the so-called modern novel.

Chiba: Hmm. I would find it interesting if it weren't for modern fiction, but for something more experimental, or something more ancient.

Kokubun: What I write may indeed be similar in form to speculative fiction, and I am very happy to be told that. The writer Onishi Giant once said that any novel has elements of speculative fiction. If you want to ask why, because novels want to solve the mystery of life, at this point any novel will become a speculative novel. I heard this directly from [the Giants of the Great West], although perhaps he did not write an article.

If so, philosophical books are also puzzles, so I think there will be such a side. Qianye Jun, you are thinking about what I am doing again, right?

Chiba: Because what Kunibi-san wrote is a speculative fiction-style unfolding, it is a premise to start reading from the front, and it is temporal. My book is considered in the direction of random acsess. So it's spatial. I think the difference between me and Kokusei your book is here. Kokubu Sang is betting his life on how to open the page (laughs).

Kokusai: Definitely let you read to the end. Definitely won't let you run away, such a feeling.

Chiba: It's too powerful to pinch, this kind of power.

Kokubun: However, at the time of Deleuze's Philosophical Principles, I was tired of reading it myself because of the speed of the straight-line onslaught (laughs). At this point, I thought it was bad at all, so at the end of each chapter, I added a commentary on the unfolding research for rest. Otherwise, I think it will become a reading that is always running on the treadmill. In philosophical books, there may not be many books that have reached this point of straight-line onslaught.

Chiba: It's usually a matter of twisting and turning from time to time, interrupting the question from time to time.

Kokubun: That's it. But in philosophical books, the kind of slow discussion while taking a long detour and then suddenly returning to the original question- this kind of unfolding book is very rare\ no, and I have been very dissatisfied with it before. There will be twists and turns along the way, but in the end "back to the original question" – I want to taste the pleasure. However, there are very few books that satisfy me, so I plan to write about it myself.

...... (Omitted)

Human beings are no longer prescribed by language

Kokubun: So far, Kiba-kun and I have actually had several conversations in several important venues. But to me, there doesn't seem to be a feeling of frequent conversation.

Chiba: Exactly. There are only a handful of conversations printed in movable type.

Kokubun: Like the Wing Jun and The Wing Jun in キャプテン翼, they occasionally form a golden combination (laughs). That's the impression.

Chiba: Personally, I talk a lot.

Kokubun: Although I often speak a little, I only appear occasionally in the world. Although it is such a rare combination, I feel that it is good to spread the things that the two of us talk about to the world.

Well, when I think about what to use as the subject of the conversation, it is really about "language". To recall, I dealt with language to the fullest in "The World of Medium Dynamics", and in The Philosophy of Learning, the first chapter of Chiba Jun also advocated being a person who was more language-oriented.

Chiba: Both are linguistics.

Kokubun: Yes. So anyway, what we're looking for is language. First of all, it is necessary to confirm the current situation of the language. Because language has really changed a lot, I feel that the language situation in the 21st century has probably almost emerged. That's a big change from the 20th century, when we started learning in the 1990s.

Chiba: That's right. When the thinking of the 20th century entered a new phase, as it is commonly known as the "turning point of linguistics", language (this thing) was first realized. Thus, the existence of linguistic consciousness at the base of twentieth-century thought (ベースにある), which should first be confirmed. Thus, if there is a weakening (weakening) of language in the 21st century, then it (thought) will turn to something different from the 20th-century model of the humanities.

In the twentieth century, the dimension of language was more important than anything else. For the liberal arts, the status of language is equivalent to mathematics for science people.

Kokubun: If the humanities do become unable to rely on language, it may be like physics cannot use mathematics.

Chiba: On the other hand, the discussion we have today deals with "language" as a whole\whole on a rather abstract level. But probably the average person doesn't grasp language by such standards. Generally speaking, if you talk about language (in everyday life), you will expect to refer to a specific Chinese such as English and Japanese. Therefore, it is a rare thing in everyday life to raise the question of language, which is the very existence of language itself— I think so.

Kokubun: That's the way it is. Let's expand on the question raised by Qianye Jun a little. This is an example I mentioned earlier, where there is a very interesting fragment in Forrest Gumpen's Use of the Body. According to Agamben, modern philosophy is essentially the study of human beings as transcendental subjects on the basis of Kant's philosophy. In contrast, philosophers such as Nietzsche, Benjamin, Foucault, and Benveniste tried to detach themselves from this and to do so by finding in language the "historical a priori" that defines humanity.

That is to say, human beings are defined by language—this 20th-century philosophy, which began around the end of the 19th century, is not a transcendental subject, but a person who speaks, a person who uses language. This is the origin of the linguistic turn.

Chiba: To add, in Kant's case, human thinking is thought to have been constrained [conditioned] by abstract rules. From the end of the 19th century, people became think of it as a historically formed language that sets the conditions for human thinking and behavior.

Kokubun: Yes. "Historical a priori" is the expression used by Foucault. Although it is both a priori and historical, it is contradictory, but in fact, if we look back at our thinking, there is actually something similar to the premise that is historically prescribed. And the search for language has become the basis of philosophy since Nietzsche.

The problem is that next, Agamben says, this philosophical attempt can be said to have reached an end point today. I quote slightly, "What has changed, however, is that linguistic activity no longer functions as a historical a priori—without thinking, as it is—as it prescribes the historical possibilities and conditions of the people who speak the language) (the Use of the Body, p. 192).

As such, the language that prescribes human beings has come to an end. Agamben's diagnosis was that human beings were no longer prescribed by language.

Chiba: The so-called "historical transcendence," despite its historicality, still exhibits the duality of something that is (itself) absolutely ahead, so I think this is precisely the term used to describe the language itself.

It is common to distinguish animals from humans by language. So where did human language ability, or cognitive ability to make human language ability possible, begin at the evolutionary level? - I don't know it very well. But on a historical level, this happened (だがそれは歴史的に始まった). However, as long as human beings exist, there is a language as a prerequisite for absoluteness. So, does Agamben mean that humanity distinguishes itself from other beings— and the way of this distinction is over?

Kokubun: Yes. To be precise, it is "animalized".

Chiba: Humans, as beings with animals and evolutionarily (spectrally) -- have become such a thing.

Kokumei: In the twentieth century, human existence was prescribed by language, which is a philosophical premise. Language is even considered a shackle that human beings cannot escape. But in contemporary times, there is a sense that language is retreating, that [man] is freed from its shackles.

As Jun Chiba just pointed out, abstractly problematizing the whole of language— this kind of thing is not common in everyday life. But in the modern era, this may be even more difficult to achieve. Even philosophy and thought will become unable to do so.

The age of directness evoking emotions

Chiba: Now, you can't grasp language without a prop-like view of language.

Kokubun: In Foucault's Words and Things (Shinji, Shinchosha, 2020), in the narrative of the 17th-century classicism era, language is seen as a transparent medium, so the existence of language itself is not seen. When it came to the 19th century, as Hölderlin's poems refer to, the language of matter as a hard, rough rock was discovered—and that was it.

From that point of view, contemporary language looks like a step back in time to the 17th century. Perhaps the difference from the 17th century is that communication is not necessarily dependent on language, but is becoming something quite emotional.

Chiba: When the emotional expression is now in front, the necessary language at the level of interpretation is superfluous. Emojis and emojis that can express emotions more directly have become popular. The so-called emoticon (emoticon) is a word made up of emotion and picture (icon), which is a emoji that expresses expressions and feelings. As this language indicates, I think that in contemporary times, with the weakening of language, we are shifting to an era of evoking emotions using images and directness.

Kokubun: What you can know through LINE and WhatsApp is that daily communication only requires memes and emojis. It is close to the type of communication that expresses joy by wagging its tail. As we said before, the weakening of metaphor and the unconscious happens at the same time.

Chiba: Speaking of which, language is troublesome because it is not a manifestation of immediacy, but is always indirect and roundabout. When one language points to something, it will provoke another language, and the meaning will be slightly deviated. Language is not directly related to reality, but is sandwiched between them. That is, language is an extension of direct satisfaction, or more simply patience. This extension of immediacy is effected by the existence of metaphors. In the activity of language, there are always some things that are impenetrable and have not reached the truth, that is, dissatisfaction exists, and around these dissatisfactions, all kinds of languages are not and are not unfolding, and thus the rich form of language is established.

However, the language surrounding such discontent has become no longer multiplying. If I want to ask why, I think one of the reasons is that direct sexual satisfaction is becoming more and more likely. Although this is a simple statement, in contemporary society, the situation of forced patience is decreasing and becoming instantly happy. That is, the conservatization of immediacy through the connection of language has become no longer necessary.

In Deleuze's letter to Foucault, desire and pleasure are opposed. Desire exists between what and what. Between the state of not being satisfied and the state of being satisfied, it is the state of striving for patience at the same time. In contrast, happiness is the end, associated with death. Foucault's words were very concerned with pleasure, but Deleuze himself said in that letter that he was more concerned with desire, which showed two philosophical directions of similarities and differences (Gil deleuze, Desire and Pleasure, Two Systems of the Madman, 1975-1982, Kawaide Den New Society, 2004).

But isn't what is found in the contemporary era a state of staying at the end of the line? This is already technically possible.

Chiba: For example, in order to manage your body purely and reasonably, you can immediately purchase and consume the exact grams of nutrients you need at a convenience store. There, there was no patience. I think that's something that should be feared, although it's really convenient.

Kokusho: In Freud's words, patience is the principle of reality. For the so-called principle of reality is an extension of the realization of the principle of happiness. Because human beings cannot cope with reality by the principle of pleasure alone, they can accept the principle of reality even if they are reluctantly—this is Freud's premise, and here, in the midst of the confrontation between the two, human growth is taken for granted. And [now] that's no longer taken for granted, right?

Use language like a toy

Chiba: Language is the distance itself relative to the situation, so the loss of language [loss] means the disappearance of distance. In this way, the distance between the hostile relations will also disappear, so it will become a direct conflict.

In other words, the materiality of language has the side of the buffer material to avoid direct conflict. The social significance of this buffer material is also linked to the existential meaning of literature or art.

Literature and art do not use language directly like props, but use language as a language. This meta-linguistic use also exists in everyday life, becoming a breakwater for society not to move in a directly emotional direction.

Kokusai: It feels like, as William Morris said, art is necessary in everyday life. Not a cup of industrial products, but a cup made from an unknown craftsman, and living while loving this cup. Live while decorating your daily life. If you think the same way about language, it would be to play between languages (言を遊ぶ).

Chiba: In The Philosophy of Learning, I mentioned the toy use of language. The so-called learning refers to stepping out of the thinking framework that has so far defined the things of one's life. Moreover, life so far is linked to the way a particular language is used, so to say that going outside of that world means changing the way language is used.

It's just that at that time, if you just move from one usage A to another, it's just a transfer to another life. What I call "deep learning" in that book is not just a transfer to another method of use, but a position that allows oneself to stand outside the environment to which I belong. To do this, we cannot use language simply as props, we must be aware of language itself.

The key here is the way toy language is used. Usually, when we say "help me get salt" or "I hate you," we think of language as something that has the power to directly cause an event, but if we look at things from the perspective of being detached from this situation, language becomes just something to say (ただ言ってるだけのものになる). It is only the language of speaking, because it is value-neutral, so the discussion is valid. While it may be a little bad to say this, it is precisely in this way that the language of speaking is considered to be deep learning, and the operation of language as a language is connected to literature as a language game through channels (スペクトラム).

Language is "magic"

Guofen: In this way, the distribution between public and non-public places becomes more difficult. When colleges started online classes, the first thing I said was that classrooms are not public places at all. Because it is not public, it doesn't matter if you can say what you like, and it doesn't matter if you make a mistake. Its closedness is important to ensure the freedom of the classroom. But, on the other hand, if the classroom is too closed, there will be a problem of teachers becoming absolute monarchs. Therefore, I think it is important for the classroom to be semi-public, semi-private, both open and closed.

But now, when you speak in lectures, don't you always have to be afraid of public things? Although it sounds a bit exaggerated, I am reminded of what Heidegger pointed out in his Letters of Humanitarianism: "Language is yielding to the dictatorship of the public" (Martin Heidegger, On "Humanitarianism"—Letter to Jean Beaufort in Paris, ちくま学ま研文庫, 1997, 26.26). I really felt that.

Chiba: It's back to the big theme of language. After all, man weaves reality through language. Because only by wrapping up the fictional level of language (レイヤ) can people survive, if they are not careful about it, they will damage human nature (間らしさ)

Language is a dangerous thing, and in some cases, a single sentence can greatly influence a person's behavior. Although people say that the power of science is like magic, I think that the actions of scientists who can make atomic bombs or other things, the language that can be changed in a word, is more like magic. But, because of this, if (in Japan and the world?) The repression of the liberal arts is on the rise right now—this may be my ironic statement—but in that sense, the contempt for language is also intensifying.

Kokubun: Impressing people with language may refer to the ability of people to create desires with language. Indeed, it was "magic." Information and numbers can give awareness, but isn't it language that is necessary to create desires? Politics is basically based on language – Hannah Arendt's proposition should also be understood to mean that it is not based on information and numbers, but on language. What moves people is language.

Senka: Repellent of the character of the Ying-essy, Yawa-yōsō losing [down] Yu. The power of the wording ability tairyo, the tao-ying,,I'm very very sorry for what,(现丢掉语边发 exhibition [Isn't it toward the direction of lessing words]?

Whether it's Tolkien or Dragon Quest, I think the magic that appears in the fictional world is basically a metaphor for language. Don't magic people also read old books? That's a metaphor for a literature researcher.

Kokubun: [Literature researcher] Just don't use that language as magic, but engage in some kind of information management.

Chiba: Information is anonymous and systematic, and it is the same no matter who sends it; but language is intertwined with human nature, human plurality. This is indeed an Arendtian statement.

A book review from a friend:

Qianye transforms DG's attitude toward emotion into a kind of emotion at the end of history, believing that at the end of history, the language of metaphor and ambiguity is dead, giving way to a language that directly calls for emotion. In fact, almost after the "loss of symbolic order" in the Higashi Hiroki period, Chiba said, "Language (metaphor and ambiguity) has also fallen." Then, in the transitional era when the metaphorical and ambiguity of language is weakening, but it is still not yet dead, we should go back and rethink the meaning of language. The concept of "subjectivization" is still a crucial issue today (the judgment of dg is basically followed here), that is, "global capitalism has deconstructed all solidities, making the exchange of anything a possible state", so the problem of subjectivization is, how to retrieve the specificity of itself (the subject)? Of course, the title of the book, "The Annihilation of Language," is nothing more than a brainstorming of possibilities, but I retain nine-in-nine doubts about the opposite axis itself.