Article source

Arab World Studies, No. 1, 2022

Executive Summary

The eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea is the meeting place of the ancient two river basin civilizations and the ancient Egyptian civilizations, and has always been a region where different cultures and ethnic groups have blended. In the middle of the 3rd millennium BC, the city-state of Ebla in northern Syria flourished, leaving a wealth of literature for future generations. Although syria-Palestine has always been regarded as a colony of Northwest Semites, Ebra has a distinct east-Semitic identity in many fields, including language, writing, religion, and art. At the same time, the Ebla culture also contains many Northwest Semitic and even non-Semitic elements. The issue of cultural and ethnic affiliation in Ebola is a classic case study of the relationship between the spread of early civilizations and the migration of ethnic groups. By analyzing the identity of ancient ethnic groups such as Ebra's language, gods, personal names, and art, this paper argues that Ebra as a whole should be regarded as an East Semitic group that has long been influenced by the surrounding Northwest Semitic culture. This mixture, based on Eastern Semitic elements, is key to understanding the issues of Ebra culture and ethnic affiliation.

keyword

Ebla; ethnic affiliation; ancient West Asia; eastern shores of the Mediterranean

About the Author

Mei Hualong, Ph.D., is an assistant professor at the Department of Western Asia, School of Foreign Chinese, Peking University

body

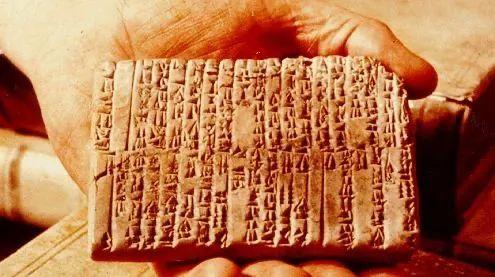

Image credit: Pinterest

The ancient state of Ebla in the 3rd millennium BC was located in the region of Syria west of the Two Rivers Valley. The heart of the Ebla ruins is the Tell Mardikh mound, located about 60 kilometers southwest of Aleppo in northwestern Syria. The city-state of Ebla was a representative political and cultural center of Syria from the mid-3rd to mid-2nd millennium BC BC. The history of the city-state of Ebla can be divided into three periods. First, the more than 15,000 cuneiform clay tablets (24th century BC) found by archaeologists in the main palace of the site between 1974 and 1975 are among the most important discoveries within the site of Ebra, revealing the first glorious and powerful era in Ebra's history, the First Ebra. Second, from the 22nd century BC to the 21st century BC, the city of Ebra was destroyed, but soon revived under the system of your Third Dynasty as the second Ebla. Finally, with the fall of the Third Dynasty of your, Ebra declined again, and only revived it after entering the 2nd Millennium BC as the Third Ebra. By this time Ebra's political position in the region had deteriorated considerably, gradually giving way to the Yamḫad kingdom, centered on Aleppo, and eventually being wiped out by the Hurrians and Hittites. Compared with the two booms of the 3rd Millennium BC, the culture and art of Ebra in the 2nd Millennium BC have undergone certain changes. Although it is uncertain who destroyed the Second Ebra at the end of the 3rd millennium BC, the Third Ebra did arise against the backdrop of the Amorites, who spoke the Northwest Semitic language, gradually came to power in the Two Rivers Valley and Syria, established many local dynasties, and eventually destroyed your Third Dynasty. In the Third Era of Ebra, the cultural characteristics of the city-state, while inheriting the style of the First and Second Ebla periods, took on the overall characteristics of the Amorite era. Considering that the city-states and territorial states of Syria and the Two Rivers region at that time were mostly ruled by the Amorite dynasty and may have been accompanied by the migration of Amorites, it is difficult to imagine that Ebola could stay out of it and be completely unaffected by the tide of Amorite immigration. In other words, Ebra in the early to mid-2000 BC period should be considered part of the northwest Semitic Amorite world.

So, who were the Eblas in the 3,000 BC period? What is the connection between them and the Amorites? Since the Amorites were seen as representatives of the early Northwest Semites, and because Ebra was located in northwestern Syria, it was easy to see Syria and the periphery of Ebra as the traditional sphere of influence of the Northwest Semitic culture. However, the historical reality of the 3,000 BC period is clearly not as clear as the Amorite era hundreds of years later. Even if the Amorites who were in the eastern two river valleys were really from the west, we cannot conclude that the Eblas in the 3rd millennium BC were Amorites or Northwest Semitics. Thus, the ethnic affiliation of the founders of the Ebra culture in the 3rd millennium BC is the central issue explored in this article.

The analysis of the attributes of ancient West Asian ethnic groups is often inseparable from clues such as pottery style, artistic characteristics, settlement and funerary customs, social structure and culture, language and writing, religious beliefs and personal names. Compared with many ethnic groups in early West Asia, Ebla in the middle of the third millennium BC left a wealth of written materials, giving scholars a more direct and relatively conclusive element of ethnic analysis relative to material culture. Academic research from the perspective of anonymology, toponymy, and Ebra language family, and the debate mainly revolves around whether the Ebra culture belongs to the Eastern Semitic tradition or the Western Semitic tradition. Among them, G. Bucheratti (G. Buccellati proposed that the relationship between Ebola and the Amorites should be understood in terms of the urban-rural rather than the eastern-Western Semitic binary. Based on written data and supplemented by archaeological findings, this paper analyzes the ethnic belonging characteristics of Ebola in the 3rd millennium BC and its development and changes in different eras from the three aspects of language, religious belief and artistic characteristics that best reflect the characteristics of ethnic groups. On this basis, this article will review Bucheratti's hypothesis and explore the issue of ethnic affiliation of the Ebra people and its connection to the later Northwest Semitic Amorites.

I. Language and the ethnic affiliation of the early Ebra

The main source of information we understand about the Ebla language is the Ebla archives written in the 24th century BC. Most of the cuneiform clay tablets unearthed by Ebla are administrative and economic documents, but also international treaties, incantations, divination, or documents of a literary and mythological nature (such as ARET V.6, 7). In terms of writing and writing tradition, Ebra's cuneiform tradition is both external and indigenous: its early writing and phonics may have been influenced by the Eastern Two Rivers Valley and Mali; since the time of King Irkab-dāmu, the Ebra cuneiform tradition has gradually taken on its own in the details of the text.

Our focus is on the language itself, especially the place of Ebra in the Semitic language and whether it is a separate language. Strictly speaking, the latter is not only a linguistic problem, but also a matter of terminology and nomenclature. More importantly, in modern society, the division of language is influenced by political and cultural factors. Some fully interoperable languages are seen as different languages as politics diverges. When discussing whether an ancient language should be regarded as an "independent" language, it is often difficult to understand the political motivations behind it, so we should pay more attention to the overall characteristics of the language and its commonalities with other languages, and explore the genealogy of language accordingly. While focusing on the overall characteristics of the language, attention should also be paid to its uniqueness, in particular the obvious differences in originality compared to the languages of the same genus, and which characteristics are influenced by other languages.

(i) The overall characteristics of the Ebra language

The Ebla language as a whole embodies the characteristics of the Eastern Semitic language and differs greatly from the Northwest Semitic language of different periods in Syria. In terms of vocabulary, Eblad has more vocabulary in common with other Akkadian dialects. In terms of verb conjugations, verbs in Ebla, like various dialects of Akkadian, use prefix conjugation forms to describe actions that occurred in the past, i.e. "preterite", unlike most Northwest Semitic languages that use suffix conjugations, the "perfect tense". Like what:

da-si-ig [tassiq] = You kissed (ARET XIII 1 r. XII 12)

daš-gul[taṯqul]=you weighed (ARET XIII 15 v. I 8; III 17)

i-sa-gur[yiskur] = he said (ARET XVI 1 r. VIII 23)

Second, the verb form in Eblad to indicate present or future also uses prefix conjugation and, like Akkadian, has an "a" between the first and second consonants of the root:

i-ra-ba-ša-am6[yirabbaṯ-am] = he (will) appeal / he will confirm his legal claims (ARET XVI 11 v. IV 5)

ne-sa-bar[nisappar]=We (will) send, send (ARET XIII 13 v. III 7)

Again, the suffix conjugation of the Eblad verb, as in Akkadian, denotes a state (Stative), sometimes with a passive meaning. In many Northwest Semitics, the suffix conjugation is the finished body, which can take direct objects.

Finally, Ebla, like Akkadian, has a verb finish with a -ta-midspecific, and this conjugation is largely absent in Northwest Semitic:

ig-da-ra-ab[yiktarab]=He has been blessed (ARET XI 1 v. VIII 15)

ne-da-ma-ru12[nītamar]=We have seen (ARET XVI 10 v. II 3)

The above features indicate that Eblad and Akkadian are highly consistent in terms of verb conjugation.

In addition, in terms of the distribution and characteristics of stems, the Causative Stem in Eblad is represented by the same as the Akkadian word -š- Of course, although the symbol of the stem of many northwest Semitic envoys is -h- or -ˀ-, the mere fact that -š alone cannot conclude that Ebola belongs to The Eastern Semitic language. In Ugaritic, as a Northwest Semitic language, the stem of the servant is also denoted by -š-.

In addition to verbs, there are several noun variations in Ebola that are consistent with Akkadian and are largely absent in Northwest Semitic, such as the noun suffix [-ūm] indicating place and the noun suffix [-iš] indicating tendency (e.g., ga-tum-ma ga-ti-iš[qātūmma qātiś], "from one hand to the other"). The masculine plural form of the adjective in Ebra is also the same as that of Akkadian (-ūtum). It is important to note that the end-of-word form of the positive plural of the Eblad adjective is not consistent with the plural of the positive noun. In Northwest Semitic, the noun and the adjective end the same. Among them, the positive plural of adjectives generally ends with -ū/īm (Ugarit, Hebrew, Phoenician, etc.) or -īn (Aramaic, Moabite, etc.).

In terms of word order, Ebra, like Akkadian, is dominated by the subject-guest predicate, but there are also two kinds of word order, the subject-guest and the subject-predicate. Among them, the guest of honor embodies the northwest Semitic characteristics, but may also be a remnant of the original Semitic language. Therefore, it can be said that the word order of the Ebra language as a whole also reflects the characteristics of The Semitic language.

(ii) Differences between Ebra and other Eastern Semitic languages

There are also significant differences between Ebra and Akkadine, which is also an Eastern Semitic language. Some of these differences seem rarer than other Akkadian dialects. In Semitic, the verb affix -t- often gives the verb a mutual, passive, or reflexive meaning (e.g., the Akkadian stem of Gt, Dt, Št; the Hebrew tD is the Hithpael stem). In Eblas, there is a form of prefixing ta-/tu-, with the suffix -ta,, which has the same meaning as a reflexive or reciprocal verb with only one -t-suffix. For example , the infinitive of the gt(n) verb stem is generally pitrusum or pitarrusum ( p-r-s ) in Akkadian ; in Eblad , it has the form dar-da-bí-tum [tartappidum ]. Similarly, the infinitive of the Št(n) stem takes the form of šutaprusum in Akkadian; in Eblas there is du-uš-da-ḫi-sum[tustaˀḫiḏum] and du-uš-da-gi-lum [tustaˀkilum]. In these examples, the form of the Ebla language is t-embellished with two t-words.

In terms of vocabulary, the prepositional sin (si-in, sometimes spelled si-ma, meaning "towards...") is not found in Akkadian or Northwest Semitic. With the exception of Ebla, this preposition exists only in Sabaean/Sabaic in Ebla and Old South Arabian dialects. There is a preposition in the Cyberjaya language, s1wn ("toward..."). S1 in Theboy corresponds to the š in the Proto-Semitic language, and this consonant is pronounced in Eblad [s], so that the correspondence between the two words is possible. This preposition may be an accidental legacy of proto-Semitic languages in two distant branch languages.

Ebla language also has two characteristic features of suspected phonetics: one is that sometimes the consonant r is written as l; the other is that the consonant l can occasionally fall off.

r is written as l as follows:

ti-la-ba-šu[tirabbaṯū](ARET XVIII 13 r. II 4)

ma-ḫi-la[maḫir](ARET II 5 r. VIII 1)

l The case of shedding is as follows:

ti-na-da-ú[tinaṭṭalū](ARET XI 1 v. V 7)

i-a-ba-ad[yilappat](ARET XI 1 v. VIII 18; 2 v. VII 25)

ne-ˀà-la-a[niḥallal](ARET XVI 5 r. V 9)

i-da-kam4[yihtalk-am](ARET XIII 5 v. X 12)

ne-mi-ga-am6[nimlik-am](ARET XVI 5 r. V 9)

We first need to be clear: do these features represent a writing or orthography problem, or a real phonetic problem? r is spelled l, and the existing evidence seems difficult to judge. The shedding of l seems to be explicitly a phonetic problem by the last example above (ne-mi-ga-am6=[nimlik-am]), because the syllables that begin with a complex consonant such as [mli] are not in line with the writing habits of cuneiform writing. At the same time, the shedding of l is not certain – many l are retained. The above examples show that l can fall off in different contexts, including between vowels, at the end of the word, at the end of the syllable before the consonant begins, and at the beginning of the syllable that immediately follows the consonant at the end of the previous syllable. However, these examples do not reflect the relationship between stress and l-shedding. The two phenomena of eblade writing l and l off may have come from the influence of the underlying language, but some scholars have pointed out that similar phenomena occasionally appear in the literature of Mali during your Third Dynasty and later ancient Babylon.

It should be noted that some of the differences between the Ebra languages and the Akkadian dialects reflect distinctly Western (Northern) Semitic characteristics. Such differences are concentrated in the lexical field. For example, in terms of personal pronouns, the "I" in Eblad is not anāku in Akkady, but is similar to the Arabic ˀanā and the Aramaic ˀánâ. In addition, many verb roots in Eblas only appear in Northwest Semitic and are not found in Akkadian dialects such as ˀhb, ˀmn, pll, rkn, rmm, skr, etc. Some roots appear only in Akkadian in the Amalna epistles, which were heavily influenced by the Northwest Semitic language, such as ntṣb. In addition, the personal prefix used for the third-person positive plural of verbs is both yi-and ti- (i-in later Babylonian and Assyrian Akkadian), and this feature is also found in Mari Akkadian, Amarna Epistles, and Ugarit. The first two were influenced by northwestern Semitic languages, while Ugarit itself belongs to northwestern Semitic languages. Finally, the prepositions of the Ebla language also often embody the characteristics of the Northwest Semitic language, such as ˁal (in... on), min (from... ), balu (no... ), bana (in... both are prepositions commonly found in Northwest Semitic (some also found in Arabic) such as Hebrew and Aramaic. Prepositions common to the Akkadian dialects of Ebra include ana (toward, to, right), in (in... Inside), ašti/išti (from... ) and so on.

Scholars have a whether these differences are sufficient to conclude that Eblad is a separate East Semitic language rather than a dialect of Akkadian. Although Ebla language differs in detail in terms of phonetic and morphological variations, there is no substantial difference in general from other Akkadian dialects. In the words of Michael Streck, the difference between Ebra and later Assyrian and Babylonian dialects is not greater than that between Assyrian and Babylonian dialects, and there are not many unique innovative features. In terms of vocabulary, the common basic vocabulary between Ebla and Akkadian dialects is many, but at the same time it is clearly influenced by Northwest Semitic. Due to the limitations of material, determining factors other than linguistic characteristics (such as political sovereignty, nationalism, etc.) are difficult to explore in this case. Based on phonetics, lexicals, syntax, and basic vocabulary, it seems that Eblad should be regarded as a dialect of Old Akkadian that is deeply influenced by Northwest Semitic (belonging to the Eastern Semitic branch of the Afro-Asian Semitic family).

Ii. Religious traditions and the ethnic affiliation of the early Ebra

(i) The native deity of Ebra

Some of the gods of Ebola appear in different types of literature, especially in the statistics of sacrifices, while others appear only in personal names. Some of these deities have distinct indigenous and Syrian features of Eblas and are less relevant to the Northwest Semitic tradition or the Two Rivers Valley traditions. Such deities include such as Kura, Išḫara, and NIdabal/Hadabal.

The dKu-ra is without a doubt the most important deity in the Ebla literature. Ebla's archives mention Kula at least more than 200 times. Most of this document records tributes to the god Kula (nindaba = "sacrifice"; níg.ba = "gift"), including gold and silver ingots, gold and silver ornaments (such as gú-gi-lum = "bracelet"), sheep, bread, and clothing. Also mentioned in these texts is the chariot in which the god Kula rides (giš-gígir-sumša-tiu5 dKu-ra..., such as AREET XI 2 23) and the temple dedicated to kura (édKu-ra, such as ARET III 800 I). It is not yet possible to map the temple of Kura to the temple in the archaeological finds, but its location is probably in or near the palace (sa.zaxki). Moreover, unlike some other deities of the same period (such as Hada in Aleppo), Kula was only enshrined in the Ebla area, so it can be regarded as the exclusive protector of Ebla. As patron saints, Kura and his consort, Barama, are closely related to Ebra's concept of king, queen, and kingship itself. Every year in January, when the Kura Festival comes, the king attends a cleansing ceremony in which the king's power is renewed. Because of kura and barama's close relationship with the goddess Nindur, who symbolizes the mother, Nyndur also symbolically gives Kula a new life at this ceremony. The scholar Zaraberger thus believes that Kura should be regarded as the so-called "younger generation" god of war. The "younger generation" refers to the fact that most of the gods are sons or subordinates of the Lord of the gods. In the Two Rivers Valley, the protector of the city-state with the characteristics of the god of war may be regarded as the son of Enlil, the lord god of the Two Rivers Valley. In Ugarit in the late 2000s BC, there is a myth that Baal, a young god with both the characteristics of the storm god and the god of war, was promoted to the king of the gods. However, Kura does not have the characteristics of a storm god. Therefore, we cannot speculate about the qualities of Kula and its relationship to other gods based on the mythological traditions of the Two Rivers Basin or the Northwest Semites. In addition, Zaraberger's research shows that while similar in name, it is difficult to determine whether there is a direct relationship between Kura and gods in Hurrians cultural circles such as Kurwe/Kura and Kurri. After all, it is inconclusive whether Ebra's "Kula" should be interpreted in this way. In addition to tribute records, Kula also appears in personal names (such as ku-ra-da-mu; šu-ma-dKu-ra), 24 times in total. In short, Kura is not a Semitic deity commonly found in Western Asia, but is a manifestation of the indigenous characteristics of the Ebla religion.

Another important indigenous deity is Ishalla, an influential goddess in northern Syria. In Ebola, Ishal (dAMA-ra/dBARA7/dSIG7.AMA/dBARA7-ra/dBARA7-iš) is mentioned more than 40 times. The literature also occasionally mentions multiple Ishhara clones, in particular the recent 20 dBARABARA7-iš/ra má-NEki and the 13-appearance of dBARA7/dGÁxSIG7-iš/-išzu/su-ra-am/muki. There is also a close relationship between Ishhara and Kula, the main god of Ebra. Although Balama was the official consort of Kura, Ishhara was seen as the patron goddess of the city-state and its rulers. The "dagxdAMA-raen" (king's sanctuary of ischhara" (dagxdama-raen) is mentioned several times in the records of the sacrifice, reflecting the special relationship between the goddess Ishalla and the king. The association between Ishal and Ebla is also reflected in the Epic of Emancipation in Hittite and Huri at the end of the third millennium BC. Ishal is described in this epic as the patron saint of Ebra, indicating that her special status in Eblah continued into the end of the 3rd Millennium BC.

The origin of this goddess is unknown. The Italian scholar A. A. Archi) believes that Ishalla has a long history and represents the underlying culture of Ebla. The name Išḫara may be related to The Semitic "š-ḫ-r". Ishhara was also seen as the consort of the Northwest Semitic god Dagan. Eventually, Ishal's influence extended to Anatolia and the Two Rivers Valley, merging with the goddess Ištar and eventually becoming one of the holi gods. In any case, the special relationship between Ishal and Ebra allows it to be classified as a native deity of Ebra with distinctive northern Syrian characteristics.

Nidabal is another important deity of Ebla, appearing 40 times in the records of Ebla's sacrifice. Nidabar's doppelgangers in various places are mostly found in the records of sacrifices. For example, "NI-da-bal lu-ba-anki" is mentioned more than 110 times, "dNI-da-bal a-ru12-ga-duki" is mentioned as many as 66 times, and "dNI-da-bal ˀa-gi-luki" appears nearly 40 times. There is also the "dNI-da-bal ˀa-ma-duki" (Hama-D'a), the city of the same name in what is now Syria. Among them, Nidabar is particularly closely related to the two cities of Luban and Arugadu, which belong to the Ebra vassal state of Ararah. The two Princesses of Ebola served as "dam.dingir", or priestess, in Luban. This doppelganger of the god Nidabal cruises between different towns (šu-mu-nígin) every November. The "dNI-da-bal sa-zaki" (dNI-da-bal sa-zaki) is also mentioned in the Ebra archives, which may be related to the Nidabar altar in Ebra's palace. As with other gods, large tributes were distributed to Nidabar. However, this god name is rare among human names. In short, Nidabal may be one of the core gods of the Ebra gods after Kura.

The three gods mentioned above are only representatives of the native gods of Ebra. They embody the religious traditions of northern Syria in the 3rd millennium BC, and some may be related to the later Holi traditions. However, this does not mean that their source is the Holi culture. In addition, while ishal's name may have a Northwest Semitic background, the main deities of Ebra as a whole have distinct local features that distinguish them from the descendants of the Northwest Semitic traditions.

(ii) The god Ebra with the characteristics of a Northwest Semitic

Northern Syria has historically been a region of cultural intermingling, and in addition to these gods with distinct Ebra characteristics, the northwest semitic gods also have a higher status in the Ebla sacrificial literature. Some of the Northwest Semitic gods, like the main Ebra gods mentioned above, had worship centers in the area and received large tributes. Among them, the most important is the Ada (80 dˀà-da) that has been mentioned more than times. Ada's doppelganger in Aleppo is mentioned 57 times, and Aleppo was a vassal state of Ebra during this period and a center of worship for the god Ada. Hadad/Haddu (Adam of the Two Rivers) was the highest-ranking wind god of the later Northwest Semitic culture, and was the most important god of the Arameans in the first millennium BC. Another Northwestern Semitic deity that is extremely important in later life is dra-sa-ap. This god with close ties to the underworld was also found in Mali and later in the Ugarit, Phoenician, Aramaic, and even Hebrew Bibles (as in Deuteronomy 32:24, "רשף").

Some of the most important Northwest Semitic names appear only in personal names. For example, il/ilum is both a common term for "god" and a specific god in Semitic. In Ugarita and other Canaanite cultures, as well as in the Hebrew Bible, El (i.e. אל, the form of El in Hebrew) is regarded as the Lord of the Gods. However, since the Ebla document does not mention the sacrificial center of Iller, "il or ilum" here may be a generic term for "god". Archie argues that early Syrian populations had tribal and even nomadic backgrounds, so explicit, city-centered worship of gods was not mature. The part of the god name in the early names did not necessarily refer to a definite city lord god. Thus, "Iller" can refer to any deity that a family trusts and relies on. In Archie's view, this also reflects the personal and family religious traditions common in the ancient Near East. Archie's views are largely credible. It is worth noting that although another northwestern Semitic main deity, Dagan, also appeared only in the name of Ebra (16 times), the sacrificial record mentions the "Lord of Tutur" (dBE du-du-lu/la-laki) more than 30 times, accepting different types of sacrifices or gifts (nindaba/níg.badbe du-du-lu/la-laki; ARET I 10 3; II 12 4)。 In other words, Dagan had his own sacrificial center in Ebra and accepted offerings such as gold and silver. Given that "El" is so common in personal names, if it refers here to the proper noun "Ilyushin", it should not appear in the name but not in the Ebra sacrificial literature (i.e., there is no altar, sanctuary of its own). Therefore, Eile may not have specifically referred to a particular deity in Ebla.

(iii) The influence of the gods of the Two Rivers Basin on Ebra

Some of the gods mentioned in the Eblas material also reflect the influence of the two river basin religions on Eblah. The Ebla sacrifice record mentions many famous Sumerian deities from the Two Rivers Valley, including Enlil, king of the gods, Enki, the god of wisdom, and his consort, Ninki, Enzu (spelled zu-i-nu in his Semitic form in his personal name, also found in the glossary VE 799), the sun god Utu, and The symbolic goddess of learning, Nisaba, and Zababa, the main god of war of Kish, a powerful country in the northern part of the Two Rivers Valley. The changing status of the Semitic goddess Ištar (spelled Asta daš-dar in Ebra) in Ebra is also noteworthy. In the period recorded in the Evra Archives, Ishtar appears in the records of sacrifice and in the names of people. These records also refer to istá doppelgangers of Ista in different regions (the plural of Ishtar also appears in TM.75.G.12717). Some documents refer to trips to the Ista Temple in Hanedu (du-duin ḫa-a-NE-dukiáš-daédaš-dar; TM.75.G.2328 R. xiii 6-11) and to the large amount of gold and silver (ARET VII 9 17:21 et al.) prepared for the "daš-dar za-àr-ba-adki" (ARET VII 9 17:21 et al.). According to the glossary VE 805, Ishta is the same as in The Two Rivers valleys in Eblah, which is equivalent to Inanna (VE 805:dinanna=aš-dar), while Inanna appears in a Hymn of Ebla (ARET V 7 V 2'). Overall, Ishtar's influence in Ebla during this period was limited. However, archaeological data from the early 2000 BC period, the Amorite period, suggests that Ishtar may have replaced Kula as the most important deity of Ebra during this period.

(iv) Other characteristics of the Ebla religious tradition

Judging from the names of Ebra, some of the elements in the names appear in the names of the gods, but they have other meanings in themselves, and they are not gods who have a center of worship. As common in the names of King Ebra - līm (tribe) and -dāmu (kinship), -šum and -zikir denote "name" or "offspring". Elements such as "king" (-malik-) and "justice" (-išar-) also appear in personal names, acting as "god names" elements. Some place names may be deified and appear in personal names, such as the powerful syrian states of Mali and Nagar in the 3,000 BC region and the name Aleppo attached to Ebra, which can serve as a divine element in personal names. Nagar's counterpart to the form of the consort of the deity, nin-nagar, appears in The Malian literature.

In addition to sacrifices, the Ebra people also won God's intervention in real life through spells, divination, and other means. These activities may also reflect Ebra's relationship with the religious traditions of the Two Rivers Basin. In the case of divination, Ebla's divination activities, like those in the Two Rivers Valley, revolve around sheep as sacrifices. The diviner takes the lamb liver out and predicts the outcome of the war and the economic situation based on the shape, texture, fat distribution, etc. of the liver. Ebla's divination terminology is also close to that of the Two Rivers Valley, such as the action of "observing" sheep's liver written ba-la-um (barûm), with Akkadish; "diviner" writing lúmáš (-máš), which in Sumerian means sheep used for divination.

Overall, Ebra's religion and beliefs embody a combination of three cultures: the native Syriac region, the Two Rivers Valley, and the Northwest Semites. First, the specific characteristics of the so-called "ancient Syria" indigenous culture are difficult to define. During this period, the Huri people and their culture, who later became active in the region, were not yet fully formed, but it can be seen from the name of the god that the religious culture of Ebra had obvious non-Semitic, non-two-river elements, such as "Kura", a name that could not be explained in Semitic or Sumerian. Second, the Northwest Semitic deities found in the Ebra data reflect the environment in which Ebra lived, and also reflect that the Amorite influence of the Northwest Semite culture was already prevalent in Syria before the rise of influence. Finally, the two river basins of mythology and religious practice (e.g., sacrifice, parade, and sheep liver divination) provided a platform for the emergence and development of indigenous traditions in Ebra. Although it is impossible to conclude that the source of Ebola's religious culture is the Sumerian and Akkadian cultures of the Two Rivers Valley, the Two Rivers civilization itself, especially its religious customs and ideas, has undoubtedly enabled the integration, development and system of indigenous customs, beliefs and values of Ebra.

Artistic characteristics and the ethnic affiliation of early Ebra

Like many other aspects of early Syrian civilization, Ebra shows a blend of indigenous traditions and foreign influences, particularly the two-river basin civilization, in the manufacture of pottery and the use of pottery and metalwork as a vehicle for figurative art and other artefacts.

First, Ebra embodied the common features of pottery manufacturing in early Syria in terms of pottery craftsmanship. Our current knowledge of pottery styles, pottery production and use in Ebla and its surrounding areas is mainly derived from concentrated excavations in several regions. Inside the city of Ebla, a large number of different types of pottery were found in the G Palace. Outside the palace, a functional collection of pottery was also found in a house (Building P4) located in the south of The P District in the northwest of the lower part of the ruins of Ebla. A large number of pottery has also been unearthed at small sites outside the city of Ebla, such as Tell Tuqan, a small regional center built after the destruction of the city of Ebla, 45 km southeast of Aleppo. Studies have shown that there is no significant difference in raw materials and craftsmanship between the native pottery inside Ebla (sampled from inside the G Palace) and outside the city (Tukan). In terms of overall production technology, the pottery of the Ebla G Palace is similar to the pottery production technology and style of the Ebla region in the same period, including Tukan, Tell Afis and other places. Among them, the production of pottery in urban areas is more inclined to produce standardized products, such as goblets, oval pots, etc. During this period, the overall centralization and standardization of pottery production in Syria was still not obvious, and it had the characteristics of polycentre.

Unlike the native Syrian character of pottery, Ebra has a local character in graphic art, with the Two Rivers Valley as its source, such as the use of cylinder seals. Among them, the imprinting of the print with different motifs is an important way for us to understand the art of Ebra images. In Ebra, the bullae and pottery surfaces used for sealing were the main mediums for the appearance of roll seals. The roll marks on the mud are often similar to the artistic style of the Two Rivers Valley in the early dynasties, but the main scenes of fighting are the scenes, and the banquet scenes are basically not found on the Ebra rolling seals. Ebla's roll prints generally consist of only one strip pattern (not two above and below), some with a strip of geometric patterns at the top and bottom, and some at the top of which there is a band of human and animal heads. Battle motifs generally involve animals (such as more docile animals such as lions, cows, and deer) humans, minotaurs, and gods. On a stamp, a Minotaur also held up a plate that appeared to consist of four human heads. On other seals there are male figures holding deer hind legs and female figures hugging cow-shaped figures. The seal pattern on the pottery, about 50 cases have been found in the Ebla region. According to the Italian scholar Stefania Mazzoni, most of the seal motifs focus on two types of pottery, the spherical corrugated jar and the spherical tripod jar. At the same time, the seal pattern on the pottery is mainly divided into two types: geometric and plant themes and fertile female motifs. Among them, the former mainly appears on corrugated tanks, and the latter mainly appears on three-legged tanks. It is difficult to determine whether the scrolled images on the pottery play a decorative, symbolic role, or an administrative category. Mazzoni points out that the seals may indicate the function of the vessel or the items contained in it. Images of fertility and grazing may be for good fortune.

In addition to the roll-print images, a wealth of artworks have been unearthed in Ebra that embody the understanding, construction, and expression of the discourse of power by Ebola's cultural and political elite. Archaeologists have found wooden statues of the king and a woman (perhaps the queen) in the G Palace, along with alabaster panels with statues of the king and his retinue. Talc male and female headdresses have also been unearthed inside the palace, possibly belongings to kings and queens. The scholar Frances Pinnock believes that the image of the king occupies a key place in the overall iconographic art tradition of Ebla and even in Syria in the 3rd millennium BC. In contrast to the contemporaneous two-river tradition, which emphasized the king's close relationship with the gods, the display of power in the Ebla region revolved primarily around the king and his family (especially the queen and her ministers) themselves, and the palace was the central area that presented these images and the value system behind them. There is not even an image of a god on the flag unearthed inside the G Palace. In addition, life-size statues of kings stand on either side of the entrance to the main hall where the throne is located. The other rooms of the palace are also decorated with panels with the image of the king. On wood furniture carved and inlaid with ornaments, a specialty of Ebra, images of kings and other royal figures also appear frequently. The artistic style of Ebra and other early Syrian political centers centered on the display of the image of the king may have also influenced the idea of kingship and its artistic presentation in later Syria and even in the New Assyrian Empire in the Two Rivers Valley. Finally, although the image of the Chinese king in Ebra's artwork occupies an important position, the king inscription commonly found in Ebra in the Two Rivers Valley has not yet been found.

It should be pointed out that in addition to the continued influence of the Two Rivers Basin, Syria, which is located at the intersection of the Two Rivers Civilization and the Egyptian Civilization, naturally has also established cultural ties with the latter. For example, an alabaster container lid inscribed with the title of Pharaoh Pepi I of Egypt from egypt's Sixth Dynasty, the palace of Eblad G, was unearthed.

In short, As an important commercial and trade town, Ebra culturally reflects the fusion of different regional characteristics. Among them, the use of roll printing makes Ebra's art take on a distinctly two-river feature. As a representative of the urban civilization of early Syria, Ebra has its own characteristics in the concept system and ideology of power expressed through art.

The Ebra and Amorites: Ethnic Affiliation or Urban-Rural Differences?

This discussion provides the basis for us to clearly answer the question of what ethnic group the Eblas belong to. Strictly speaking, our inferences are limited by the inability to confirm whether the rulers and commoners of the Eblad region belonged to the same ethnic group, and the vast majority of documents and archaeological sources that only provide information about the ruling class. If the linguistic and religious characteristics of the Ebla ruling class reflect the origin of the founders of the Ebla culture, the culture already had a distinctly mixed character in the early days. First, Ebla is an East Semitic language with local characteristics. Second, although Ebra's most influential deities, such as Kula, may have a non-Semitic background, and some were later incorporated into the Holi gods, many of Ebra's important deities were crucial in the later Northwest Semitic religion. Finally, artistically, Ebra is characterized by both the Two Rivers Basin and the Native Syria. In addition to these three points, it is also important to note that the native names of Ebra are mainly Semitic names and mostly have Northwest Semitic characteristics. There were also names of unknown ethnic groups on the northern edge of Syria during this period, which are completely unexplainable in Semitic or Sumerian. At least a small part of it may be related to the Huri people, who later became very important in the region. In short, the early Eblar culture was characterized by a mixture of eastern and western Semitic and non-Semitic.

Thus, the characteristics embodied in the early Eblar culture are difficult to attribute to any particular ethnic group. It is worth noting that in terms of language and religion (especially the elements of the name of the gods in personal names), the traditional sources that play a mainstream role are the Eastern and Western Semitic traditions, respectively. So, should the creators of Ebla culture be classified as East Semites or West Semitics? Did the East Semites adopt certain beliefs and cultural elements of the Northwest Semites, or did the native Northwest Semites learn the East Semitic language and cuneiform script?

The Italian scholar Giorgio Buccellati took a different approach, arguing that in the 3rd millennium BC, the "Northwest Semit" as a concept of culture-language-ethnic groups may not have yet appeared, so the "east-west distinction" did not exist. He argues that the Amorites, who were later regarded as early representatives of the "Northwest Semitic" culture, should not be seen as a group that had a special connection to the "West" orientation and was linguistically and ethnically distinct from other Semitic peoples. Under the influence of natural conditions and corresponding economic models, Semitic inhabitants living in the countryside may be semi-nomadic in some parts of southern and eastern Syria due to insufficient precipitation. At the same time, rural life has made them both subordinate to a political entity with the city at its core and gradually distinguished it from the inhabitants and culture of the city. Even their language gradually became distinct from that of the city dwellers, resulting in a sort of "sociolect" rather than a dialect of traditional language influenced by geography. The so-called Amorites are rural people, and they correspond to the population of urban centers such as Ebra and Akkad. The two languages were not completely separated at the time, but the rural dialects were more ancient. If Bucheratti's claim holds, then it seems that we can assume that the so-called "Northwest Semitic" element in Eblas is only a common feature of the northern Semitic languages that have not yet diverged (such as the "southern" region with the Arabian Peninsula as a Semitic language). These elements have been preserved by the persistence of the rural language, but have disappeared in the urban language of Akkadhi. In this way, the ethnic background of the Ebla culture should be classified as some kind of northern Semitic culture mixed with rural linguistic characteristics, and has nothing to do with the "east" and "west" divisions.

However, while Bucheratti's theory is not lacking in novelty, there are some problems that remain unexplained. First, if the internal differentiation of the Semitic languages of the northern 3,000S BC period is not bounded by east and west, but rather the duality of urban and rural areas, then why is there a large gap in dialects between different urban centers? As mentioned above, Ebla language differs greatly from the Sargon Akkadian (also an urban dialect) in terms of vocabulary (prepositions, verbs) and some morphological and phonological features. This difference is precisely a regional difference rather than a rural-urban difference. Secondly, according to Bucheratti's logic, it may be inferred that since the rural language, that is, the Amorite language, is ancient, the "Northwest Semitic" characteristic of the Ebra language is also because of the existence of antiquity, and the reason for the survival of antiquity is that they are greatly influenced by the rural population (that is, the Amorites in his eyes). However, according to the Evra literature, the Amorites (known in Sumerian as Mardu in the Eblas literature) in Eblas appear to be seen as a political entity located in present-day central and eastern Syria that stretches northeast from Palmyra to the Euphrates River, and the Ebulah literature also mentions the "king" of Amorites. Thus, the Amorites and Ebra appear to be two separate groups. Bucherati herself believes that there seems to be no Amorites within Ebla. If the Amorites had little direct influence in the Ebla culture, then why did the Ebra language "survive" and differ from the Eastern Akkadian language? Bucheratti's theory fails to answer this question. Again, is the Amorite language really ancient? In fact, we know very little about the Amorite language of the 3,000 bc period, and most of them can only be understood by personal names. To determine whether a person's name is Amorite or Akkadian, sometimes only look at whether the verb prefix is ya-or yi-. The lack of an incomplete body with a prefix plus a double-written second root letter in extant Amorite names and an explicit, object-suffix conjugate (the suffix conjugate in a personal name is distinguished from the verb state type). It is precisely the presence or absence of these two characteristics that affects our judgment of whether a Semitic language exists or not. Therefore, Bucheratti's conclusion that the Amori language is ancient is actually difficult to prove.

Combining some of the cultural characteristics of Ebla in the foregoing, we may wish to make a more concise point of view: that the inhabitants of Syrian city-states such as Ebla and nearby townships and even some villages are Eastern Semitic immigrants, who themselves speak the same language as Akkadian in the Two Rivers Valley. At the same time, the Northwestern Semites, represented by the Amorites, had formed another ethnic group that was linguistically and religiously distinctive by that time, and the rural areas of Syria were precisely their settlements. After a period of coexistence and exchange, the East Semitic population of Ebra absorbed the existing Northwest Semitic elements in language, religion, personal names, and even art. In terms of language, morphological variations and syntax are basically similar to those of Akkadian in sargon's time, but the lexical level has a northwest Semitic feature, which indicates that Ebla is essentially an Eastern Semitic language. Grammar and morphological changes are conservative, and the vocabulary is widely influenced by Northwest Semitic, which is also in line with the occurrence of borrowing phenomena in language contact. In terms of religion, personal names, etc., the influence of non-Semitic and Northwest Semitic elements is even greater. The Northwest Semitic and non-Semitic cultures of Northern Syria during this period may have been low-level cultures, or perhaps the same as the Eastern Semitic cultures, which were immigrants, but they all added new colors to The Eastern Semitic cultures such as Ebra.

5. Conclusion

The 3,000-century BC Syrian culture, represented by the city-state of Ebla, shows us the characteristics of early civilizations on the eastern shores of the Mediterranean. Syria at this time clearly had the characteristics of the East Semitic culture in the Two Rivers Valley in terms of the basic attributes of civilization (language and some religious characteristics). At the same time, the characteristics of the Northwest Semites have penetrated into language, personal names, religion, and art, and in some ways even play a mainstream role. This article argues that East Semites are the main body of their ethnic culture, mainly because their language belongs to East Semitic. The emergence of The Eastern Semitic language in Syria, the later Northwest Semitic language area, may be because the Eastern Semitic language was widely used in the early Syrian city-states, and then gradually engulfed by the Northwest Semitic population; or because the Northwest Semitic population has long lived here, and cities such as Ebra are "language islands" formed by the foreign Eastern Semites. In either case, it is clear that the inhabitants of Ebra in the third millennium BC and their cultural origins were the same as the inhabitants of Akkad.

This conclusion is not surprising. In fact, as early as the end of the 4th millennium BC, the development of early civilization in West Asia was closely related to the outward expansion of the core area of the civilization in the Two Rivers Valley. During this period, the economic and cultural level of the Sumerian region in the southern part of the Two Rivers Valley reached a certain height. At the same time, in order to better control the resources and trade routes far from the Sumerian city-states, sumerian political forces represented by Uruk began to expand outward, establishing colonies and strongholds in Iran, the northern Part of the Two Rivers, Anatolia, and the Habur River and Balikh River in northern Syria. This wave of urbanization continued in northern Syria until the end of the early 3rd millennium BC. Of course, since no Uruk-type pottery has been found in the Ebla region, it should not be a direct product of Uruk's expansion. Some scholars believe that the initial development of Ebla may have stemmed from the second wave of urbanization in northern Syria that began in the mid-3rd millennium BC after the end of the Uruk expansion. Factors contributing to the second wave of urbanization may also include a second wave of migration from the core of the two river basins. In the mid-3000s BC, The East Semitic-speaking population, like the Sumerians, was a propagator of cultural elements of the Two Rivers Valley, probably migrating westward and establishing a city-state civilization in syria. Ebra, who speaks Eastern Semitic, is one of its representatives. Of course, as of the twenty-fourth century BC recorded in the Ebra literature, the Northwest Semitic and non-Semitic elements of Syria had also become an integral part of the cultural identity of Ebra. In short, Ebra provides us with a classic case study of the relationship between the spread of early civilizations, the establishment of political power, and the migration of ethnic groups in terms of language, writing, religion, personal names, and art.

(The views in this article are only the personal views of the author and do not represent the position of the Shanghai Foreign Middle East Research Institute and this WeChat subscription account.) )

This subscription account focuses on the major theoretical and practical issues of Middle East studies, and publishes academic information on the Middle East Research Institute of Shanghai Chinese University.