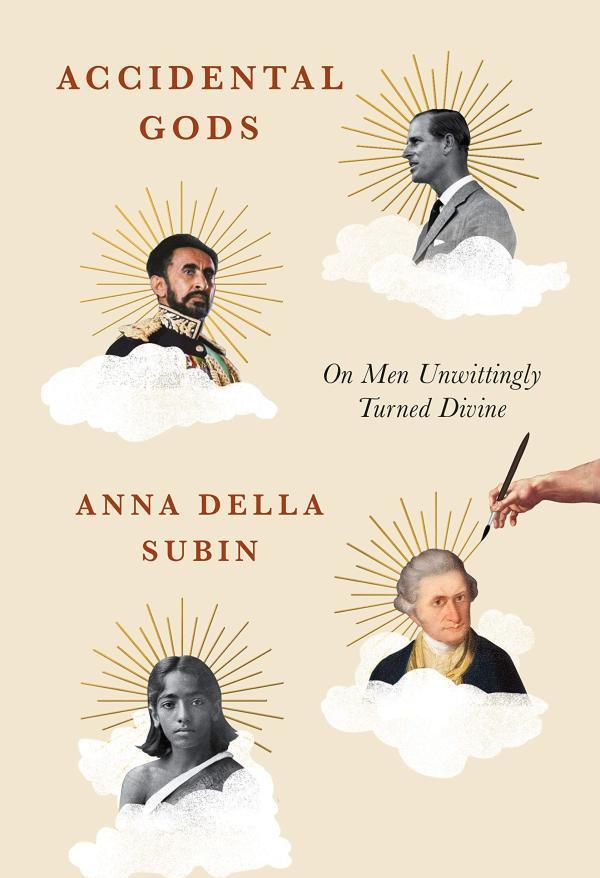

Accidental Gods: On Men Unwittingly Turned Divine, Anna Della Subin, Metropolitan, December 2021, 462pp

In October 1492, Christopher Columbus's first act after he thought it was a landing in India or Japan was to declare possession of the land on behalf of the Spanish crown. He then distributed cloth hats, glass beads, broken pottery pieces, "and many other worthless things" to the local population, who recorded in his diary that they were "very simple" peoples who could easily "imprison ... (and) enslave them and force them to do things." The locals reminded Columbus of the natives of the Canary Islands, the latest victims of the Conquest, Christianization and Enslavement of the Castilians at the time, "who were of the same skin color as the Canarians, neither black nor white".

Columbus also believed that the "Indians" regarded him and his crew as a descending god. He left his initial description of this two days after landing, although he was still unsure at the time: "They seemed to be asking if we were from heaven. Speculation quickly turned into conviction. Although the locals "regret not being able to understand me, and I can't understand them," Columbus confidently speculated that they were "convinced that we came from heaven." Every tribe he met seemed to have the same idea: and that explained why they were all so friendly.

In the decades that followed, this idea became an essential element for Europeans to describe their encounters in the New World. According to the Sixteenth-century General History of All Things in New Spain (compiled by a Franciscan monk in Mexico), Hernán Cortés lightning conquered montezuma's empire in 1519 because the Aztecs mistakenly believed that he was "the god of Quetzalcoatl (the feathered serpent god) who had been waiting for his arrival" in the sixteenth century. The following year, the Magallan fleet, which was circling the Cape of South America, encountered a tall native who "began to be surprised and frightened when he came before us, and he held up a finger high, thinking we were from heaven". The Incas in Peru initially accepted Francisco Pizarro as an incarnation of the god Viracosa, so one of his companions later wrote that the conquerors were worshipped because "they believed that there was a certain divinity in the conquerors."

This is a well-known and repeatedly stated exception. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, whites who traveled to other parts of the world to colonize were almost no longer surprised when they encountered similar instances of mistaking them for gods. After all, this error seems to encompass the innocent ignorance, low intelligence, and instinctive obedience of the people they were born to rule. What's more, as Anna Della Subin explores in her refreshingly original book, Accidental Gods, this inadvertent worship of god is a very common phenomenon that spans centuries and continents.

In Guyana, the enduring "Voltari" prophecy gave Sir Walter Raleigh a divine help against the Spaniards. In Hawaii, the death of Captain James Cook is thought to be the result of a tragic deification of a man who was mistaken for a god. Across British India, many shrines appeared around the graves and statues of colonists, who were worshipped as gods with supernatural powers. Sir Thomas Beckwyth has a clay doll modeled after him on his mausoleum in Mahabaleshwa, which is enshrined on plates of hot rice. The former Governor- Lord Cornwallis hung a wreath of flowers on the statue in Mumbai for many years, and the faithful went to visit and pray for blessings to see him and stain the "darshan".

The fate of Christian missionaries who fought for the sake of the local pagans to get out of the way was similar. James Crowe of the Presbyterian Church, the first pastor of St Andrew's Church in Mumbai, has become an object of pagan worship, despite having returned to Scotland many years ago. The church's "local servants" performed a ritual for the portrait in the church's vestment room and tried to take the fragments from the canvas as personal amulets.

Known for his cult of personality of the murderous soldier John Nicholson, a staunch Northern Irish Protestant who began his career in the disastrous British invasion of Afghanistan in 1839, he was promoted to deputy district commissioner stationed in Peshawar and Rawalpindi. The brutality of this man is indescribable, he has a severed head on his desk for a long time, he has a huge hatred for the entire subcontinent, and he has begged his superiors to allow him to strip or puncture suspicious rebels alive — his instinctive habit of violence has led him to think that "just hanging" disobedient Indians can "make people jump like thunder". However, before he led the relentless British invasion, massacre and plunder of Delhi in 1857 and finally died in it, hundreds of "Nikasani" followers worshipped him, including local soldiers and ascetics, and despite his own reluctance, the faithful always surrounded him, solemnly reciting prayers and paying homage to their idols.

General Douglas MacArthur, the conqueror of World War II, encountered a similar situation. From Panama to Japan, from Korea to Melanesia, his image has been endowed with different deities, carved into wooden idols, placed in shamanic shrines, seen as surreal figures, and seen as the embodiment of the Papan god Manarmakeri, whose return will herald the age of heaven. Even Western anthropologists are often drawn into such value systems as involuntary deities, despite their attempts to describe them as neutral external observers.

Resistance is always futile: denying one's own divinity never seems to be able to eliminate it. Nicholson was deeply disgusted by being adored. He angrily rebuked the "Nikasani" believers who followed him, kicked them to the ground, brutally beat and flogged them, and tied them up with chains, but the believers interpreted all this as "the righteous punishment of their God." Gandhi began repeatedly declaring "I am not a god" from the early 1920s, but to no avail, as stories of his supernatural powers grew, and people who wanted to touch his feet kept pestering him. The word 'Mahatma' stinks in my nostrils" – "I am not God; I am a man".

In 1961, a group of Jamaican Rastafarians traveled to Addis Ababa to meet their living deity, Hale Selassie, for the first time. They disagreed with the elderly Ethiopian emperor's own position on the issue. These apostles believed, "If He does not believe that He is God, we know That He is God." "The Government of Jamaica, which was in a desperate mood at the time, invited Selassie to a state visit in the hope that Selassie's public denial of the delusions of his followers would weaken the growing power and political influence of this faith movement. The diminutive, seventy-year-old man arrived in the Caribbean with courtesy to his dazzling followers: "Don't worship me, I'm not God." "But this has only had the opposite effect, because rastafarian theologians are well aware of the bible's teachings." Whoever exalts himself will be humbled, and whoever is inferior will rise to a high. ”

How should we view these events? As described in "Accidental Canonization", observers from Europe quickly came to seemingly obvious conclusions. This accidentally canonized divinity reflects the indigenous people's recognition of the great image of their rulers personally. Nicholson was worshipped because he was the epitome of "the best, the most masculine, the most noble," as a typical Victorian ode put it. And why this cult is sometimes directed at some arbitrary, vague, and non-heroic figure (violent sadist, deserter, nameless wife of a white ruler, etc.) is buried under the accepted notion that weak natives are subject to their masculine conquerors.

This is also considered evidence of the mental retardation of indigenous peoples. As the academic study of religious belief developed in the nineteenth century, European scholars' definition of "religion" led them to classify the practice of "uncivilized race" as superstitious, outdated, or "degenerate"—thus further justifying colonialism. In contrast to the "true" religion (most importantly Christianity) with fixed temples, scriptures, and "rational" monotheistic worship, they considered the beliefs of the "lower races" to be at an early stage of development. The worship of deified mortals is a primitive classification error, and "the irrational, misplaced piety of the natives leads them to fend for themselves," one of the many golden verses in Subin's book sums up this: it proves that they are incapable of ruling over themselves.

In fact, starting with Columbus, Europeans have repeatedly fallen into situations that they did not understand correctly, and then they have always re-described the meaning of these situations as a way of justifying their actions. The indigenous discourses and rituals they encounter throughout the Americas, the Pacific, and Asia are actually often used in fact to rulers and other powerful figures, not just gods, and only to show reverence, rather than some kind of demarcated, non-human, "god-like" status. Similarly, since people who die cannot be reincarnated, Indians have for thousands of years been accustomed to appeasing powerful souls who have been trapped forever in the underworld – which is why they have singled out many of the various British who died prematurely to be treated the same way, not in awe of white power. The deification of the living colonizers is not usually for the sake of their honor, nor is it intended to reflect certain individual virtues: it is simply a way of mediating and appropriating their power, a way of creating collective meaning in the turmoil and violence caused by imperialism.

Above all, the idea of a binary opposition between man and God is itself a distinct dogma of Christianity. In most other belief systems, the two are not strictly separate, but overlap. Reincarnation, theosophical, living Buddhas, possessed, demigods, the power to see ancestors as gods, and kings and lords—all of these are part of a spectrum of natural and supernatural powers. The same was roughly true of ancient Europe. The ancient Greeks believed that it was normal for man to become a god. In Rome, deification was an instrument of national politics and the ultimate form of remembrance. Cicero wanted to deify his daughter Tulia; Hadrian made his wife and mother-in-law, as well as his young lover Antinus, a god. For the emperor, this became a regular honor — it is said that on his deathbed in 79 AD, Vesbastian joked, "Poor me, I'm about to become a god." ”

A similar concept circulated among the early followers of Jesus. It was only from the Middle Ages that Christians considered the concept of mortals to become gods absurd, even though their own prophets, saints, and sages practiced similar principles. Modern Europeans, on the other hand, ventured far and wide and began to impose their own classification errors on other people's opinions. As Subin sharply dissects in his book: "The correct knowledge of divinity is never the question of which doctrine is best, but of who has a more powerful army." ”

"AccidentalLy Sealed God" is simple and fun to read, and it also includes a series of lyrical and thought-provoking meditations on the grandest themes of humanity. How should we think about human identity? What is the meaning of being human? How does the narrative work, grow, and stay alive? According to Subin, faith itself is both a series of relationships between people and an absolute, black-and-white state of mind. Europeans once defended colonialism and white supremacy theories with myths that describe the primitive mentality of others, and this is still the case. The treatment of indigenous customs as contrary to the "rational" assumptions of "developed" cultures has always led Western observers to ignore their complicity in creating these views, and to regard them merely as errors stemming from "superstitious ideas, silo tendencies", "not the product of imperial violence and the new capitalist profit machine that binds the people".

Such mistakes also help obscure the extent to which Western-style positions depend on their own magical forms of thinking. For example, our culture is obsessed with goods, money, and material consumption as indicators of personal and social well-being. What's more, as Subin points out, none of us can really get out of this fixed relationship:

Although we can dissolve the gods of others and tarnish their idols, our ability to critique commodity fetishism and disenchant it still cannot break its spell on us, because its power is rooted in the deep structure of social practice rather than simple belief. While fetishism created by African priests is denounced as irrational, fetishism in the capitalist market has long been seen as a microcosm of rationalism.

Mastering a myth in its entirety is another matter entirely than merely observing it. This myth flips out different surfaces, changes its shape, slips out of grasp, and disappears out of view. The further Subin explored, the more fragmented her sources of information became, and the greater the gap between the chosen concerns of those sources. But more than once she has been able to depict in near real time how indigenous and Western mythological shapings are intertwined, coexist, and reinforce.

Since the "discovery" of Captain Cook in 1774, the island of Tanner in Melanesia has been nearly destroyed by centuries of colonial exploitation: residents have been kidnapped to provide cheap labor, vegetation has been cut down for short-term profits, and culture has been destroyed by missionaries. This encounter in the early twentieth century sparked a series of indigenous saviours and movements, hoping to expel colonists and restore a golden age of abundance. It is believed that the Savior will incarnate as the local volcano god, although it is not clear what exactly human form he will appear in.

One idea that has been popular for many years is that the savior will appear as an American (it could be Franklin Roosevelt, or it could be some black soldier). That's because the island was under British and French control — a deification movement sparked by colonial injustices that often sought to gain the power of rivals or enemies who enslaved them. In 1964, the lavongai people of occupied Papua and New Guinea organized elections in which their colonial rulers wrote down President Lyndon Johnson's name and elected him king, and refused to pay taxes to their Australian oppressors. For similar reasons, certain religious denominations in India and Africa in the mid-twentieth century sometimes worshipped the image of the British enemy – in India, Hitler was seen as the ultimate mortal of Vishnu, while Nigerians worshipped "Germany, the destroyer of the land". The enemy of the enemy is my ally.

During World War I, the aborigines of the distant Allied colonies independently developed a cult of Kaiser Wilhelm II, believing that Kaiser Wilhelm II would soon sweep away the English-speaking whites who stole their land and exploited their people. On the plateau north of the Bay of Bengal, on the plateau of Jota Nagpur, tens of thousands of Oraang tea plantation workers gather in secret midnight ceremonies, vowing to exterminate the British. They referred to the Germans as "Suraj Baba" (the sun god), passed on portraits of emperors who were considered gods, and sang praises to him for expelling the British and establishing an independent Orion regime:

Germanic Baba is coming.

Come slowly and slowly.

They cast out the devils.

Throw it into the sea and go with the flow.

Suraj Baba is coming...

What stands out in this story is not this disconnect between hope and reality, but what they say. What can powerless people do? In the face of endless failures, who can they appeal to to restore the proper order of things? In 1964, a Papua skeptic challenged an apostle of President Johnson's faith and asked, "Did you know that America killed all black people?" "You are wise," replied the apostle, "but there is nothing good you can do to save us." ”

Around the same time, the British colonists on Tanner Island were instilling the virtues of the young Queen Elizabeth II and her handsome husband in the local population, informing them that the king was not actually from England, or Greece, or some particular place. Coincidentally, the legend of the volcano god also tells that one of his sons has turned into human form, gone high, and married a powerful foreign woman. Prince Philip once vacationed in the archipelago and participated in a pig-killing ceremony dedicated to a local chief. He was Duke of Edinburgh, and the archipelago where Tanner Island was located was once known as the New Hebrides. In 1974, one of the many local Saviours realized that this man must be their Savior.

This proved to be a match made in heaven, as the British royal family became increasingly dependent on invented rituals and created myths as its authority declined. Upon learning of the Prince's deification, Buckingham Palace immediately began to celebrate and promote the story, subtly positioning it as evidence that the Royal Family (and by extension, all britons) were widely loved throughout the former British Empire, and in this way balancing the Prince's bad reputation as an incorrigible racist at home. This Westernized interest, in turn, attracted a steady stream of international attention and visitors who came to Thanna to investigate and report on the strange "cult" of the islanders, which not only helped to strengthen the myth's appeal in the local area, but even influenced its form.

A BBC reporter came to the island in 2005 to report on the "faith" and brought with him a pile of documents compiled by the prince's former private secretary, including official letters from the 1970s, news clippings and other English descriptions of the islanders' beliefs. His sharing of these documents, and his lengthy discussions with locals, inadvertently sowed new myths, a large part of which, as Subin sarcastically points out, sounded "like a pry draft of the court describing charitable activities in underdeveloped areas." Myths remain alive through constant adaptation, inclusion, and complementarity. This is a classic example of the interaction between the two sides shaping the myth: the deification of Prince Philip originated from Buckingham Palace and Fleet Street, but also from the South Pacific region. To this day, white men from Europe and the United States continue to land on Thana Island, claiming to be fulfilling the prophecy of the god of return.

In Subin's irresistible history, anthropology, and exhilarating and brilliantly written golden tunes, the most powerful stories are those that became the shaping of indigenous myths that became radical political revolts. In many cases, the purpose of turning whites into gods was completely subversive: not just to channel the forces of the colonial empire to achieve its own goals, but to grasp the power of the colonizers and make them stand against them. In 1864, the Maori revolt, led by the Prophet Te Ua Haumene, killed several British soldiers and pierced the captain's head on a wooden stick, becoming a protector for the rebels against other white invaders, who also regarded it as a sacred connection with the angel Gabriel. Just as they reinterpreted the Bible to mean that Maori land should be recovered and the British should be driven away, they borrowed the real mouth of a colonizer to tell the truth that belonged to them.

Even more disturbing is the fact that, beginning in the 1920s, the rulers of Britain, France, and Belgium discovered a strange soul-possessed infectious disease in newly conquered African territories, and indigenous peoples suffering from this disease would transform into colonists. People, after falling into a trance, claim to be communicating with the Governor of the Red Sea or a white soldier, secretary, judge, or imperial administrator. Demanding hoods, drinking gin, marching in droves like zombies, giving orders, and refusing to obey the orders of the Empire, the infected patients in the Sahel region on the southern edge of the Sahara Desert called themselves Hauka, or "madness," and in Ethiopia and Sudan they called themselves Zar.

A version of the disease that is prevalent in congo claims to have created deified replicas for every Belgian colonist. Whenever an African veteran joined the movement, he would follow the name of a particular colonist, while his wife would follow the name of that spouse. In this way, Hauka took possession of the entire colonist community, from the governor to the lowest clerks. After the aborigines went into a trance, they usurped the authority of the colonists: their wives painted their faces in chalk, put on special clothes, shouted in shrill voices, demanded bananas and hens, and held a bunch of feathers under their arms, representing handbags.

Because this soul possession was not deliberate and torturous, it became a means of resistance that was difficult for the imperial power mechanism to easily resolve. At first, a district commissioner from Niger named Major Horace Crosikia decided to suppress it by force. He rounded up sixty major Hauka psychic mediums, chained them up and brought them to the capital, Niamey, where they were imprisoned for three days and three nights without food. Then Crosikia forced them to admit that their spirit could not be compared with the power of his Buddha-figures, and mocked them that Hauka had disappeared. He teased repeatedly, "Where is Hauka?" She also beat one of the mediums until she admitted that the possessed soul had disappeared.

This makes the situation worse. A new, extremely powerful deity immediately joined the Pantheon of Souls. Throughout Niger, the villagers are now possessed by the retributive and violent incarnation of The Venetian Androscopic Krosichia himself– also known as Crocisia, Conmandan, Major Mugu or the evil Major. Such acts of deification are a ritualized revolt, a defiance of imperialist power that not only mocks but also seizes its authority.

All of these examples also explain why, in the mid-twentieth century, a powerful, proud, anti-imperialist black ruler would rise up in the heart of Africa and be able to enchant people on the other side of the globe who had been dehumanized for centuries because of the color of their skin. For the blacks in the New World who are in babylon, Ethiopia has long been seen as their Zion, the land they will return to in the future. Even before Ethiopia's new emperor ascended the throne in 1930, the United States and Jamaica had prophecies heralding the arrival of the black Messiah. Rastafari became the religion of all who opposed white hegemony: to worship Haile Selassie as a living deity was to oppose colonial Christianity, racial hierarchies, and subordination, and to celebrate the power of blacks. It's no wonder its credo spread across the globe, attracting nearly a million followers. As Subin's informative and fascinating book demonstrates, religion is a symbolic act: although we have no control over our circumstances, we all continue to make our own gods for our own reasons.

(The original English version of this article was published in the New York Review of Books on January 13, 2022, with the author's permission to translate)