As modern warfare becomes more lethal, it's reassuring that today's soldiers have a better chance than ever to survive the wounds of war. In Afghanistan, battlefield first aid, rapid evacuation, and rapid arrival at military field hospitals have saved thousands of men and women who could die. Notably, these casualty management procedures did not change much from when they were adopted by the Federal Army in the 1860s.

In the early days of the Civil War, innovations in battlefield health care emerged in response to the harsh conditions faced by wounded soldiers. A classic example is the Battle of The Second Manassas (the Second Bull Run of the Confederate Army), in which the Confederate Army defeated the Northern Army in a clash in late August 1862. More than 22,000 soldiers were killed or wounded in the Virginia conflict, nearly 14,000 of whom were in the Union Army. Wounded soldiers were scattered across the battlefield, in dire need of water and medical care. As time went on, their screams and groans grew louder. A full week passed before all the wounded of the Union army were transferred from the battlefield to hospitals, which was a terrible testimony to the army's inefficiency in dealing with the wounded.

Incredibly, just two weeks later, the condition of the wounded changed. On September 17, 1862, the Northern and Confederate armies fought another Battle of Antitam in Sharpsburg, Maryland. After 12 hours of fighting, about 23,000 men (more than 12,000 Northern soldiers and more than 10,000 Confederate soldiers) were killed, the bloodiest day in American history. In stark contrast to the delays on the battlefield of Manassas, all wounded Confederate soldiers were evacuated from the battlefield of Antitam within 24 hours.

What changed all this was a slender, bearded man who looked like Donald Sutherland — a 37-year-old military doctor, Major Jonathan Letterman, who was appointed medical director of the American Podomac Legion Association three months ago. Letterman's genius was evident the moment he took on his new role. He immediately undertook revolutionary reforms in battlefield casualty management, and in Antitam he began to pay off. Letterman's innovations were so visionary that they are still in use today, earning him the title of father of war medicine.

To hasten the evacuation of the wounded, Letterman created the first ambulance team of the Federal Army. He established a unified system of first aid stations and field hospitals, bringing order to the previously chaotic and inconsistent treatment of the wounded. He also ensured that medical units were provided with the necessary equipment and supplies. Long before the introduction of the classification system for medical evaluation in World War I, Letterman developed criteria for prioritizing treatment based on injury severity and likelihood of survival. Thanks to his efforts, thousands of soldiers survived, otherwise they could have died in their wounds.

Born in 1824, Letterman was the son of a prominent penn surgeon. He grew up in Fort Cannon and graduated from the local Jefferson College in 1845. After graduating from Jefferson Medical School in Philadelphia four years later, he immediately applied to become a military surgeon. He was stationed in California at the outbreak of the Civil War and returned to the East at the end of 1861. In May of the following year, he became director of the West Virginia Department of Medicine, followed by his appointment as Director of The Medical Department of the American Society of the Army of the Boltom. At the time, the Potomac Corps was in a state of regret, with thousands of soldiers wounded and sick. Letterman realized that many soldiers suffered from scurvy, and he quickly cured it by increasing the rationing of fresh vegetables. Other problems are not so easy to solve.

Letterman and his Fellow Civil War physicians had to deal with massive battlefield casualties that no one could have predicted. The Second Battle of Manassas alone produced twice as many casualties as the entire Revolutionary War. The appalling massacre was the result of improved weapons and outdated military tactics. Generals on both sides still used napoleonic large-scale attacks, yet in the face of new types of weapons, such frontal attacks amounted to suicide. It was not uncommon for troops to lose a third or more of their soldiers in a frontal attack.

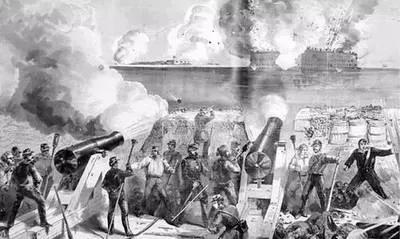

More than 90 percent of the wounds in the American Civil War came from gunshot wounds, most of which came from unsightly half-inch-long metal projectiles fired from Springfield rifles, a soft lead bullet that can break a person's bones and punch a fist-sized hole in a person's body. The other two extremely effective projectiles are shotgun shells and grape shells—cannonballs loaded with dozens of small iron balls. When the shells were fired, their shells cracked, and iron bullets shot at oncoming soldiers in the Wall of Death, like a giant cut-short shotgun.

Throughout the war, extreme battlefield casualties and unusually heavy casualties placed a heavy burden on the heavily understaffed Army medical teams. In 1860, the U.S. Army had just over 100 doctors to treat 16,000 soldiers. Although by the end of the war the medical corps had increased to more than 10,000 surgeons, the ratio of doctors to soldiers had actually declined, since by 1865 the Federal Army had expanded to well over 2 million men. (The Confederate doctors faced an even more difficult situation, with only 4,000 doctors to treat more than 1 million soldiers.) )

In addition to having too few doctors, the military had to rely on doctors with basic skills. Basic medical procedures have not changed much over the generations. Doctors usually receive only simple training, usually in non-standard two-year medical schools. Most new doctors have never treated a gunshot wound or performed any form of surgery. They were truly trained to heal the unfortunate soldiers lying on the operating table. Thankfully, chloroform was widely used years ago, and morphine and opium could also be used to alleviate the suffering of soldiers.

Since most Civil War-era doctors were not eligible to operate on severe wounds on the head, chest or abdomen, these wounds were considered fatal and were often not treated except for painkillers given to the victims. The most common wounds are limb injuries, making amputation the most common surgical procedure. A skilled surgeon can cut off a severed arm or leg in ten minutes with all sorts of terrible knives and saws.

In the heat of the fighting, the typical field hospital looks like a scene from Texas Chainsaw Massacre, with surgeons splashed with blood clots and parts of the wounded body falling on a strange pile of stuff. Surgeons struggled to work amid the screams of the wounded, the explosions of cannons and the sound of musket fire at hand. As they bent over the operating table for hours on end, sweat and blood flashed on their bare arms.

Unaware of the relationship between bacteria and infections, Civil War-era doctors used the same surgical instruments over and over again, even bothering to sterilize them, leading to postoperative infections, including blood poisoning, tetanus, and gangrene. Despite the lack of surgical hygiene, almost three of the four amputees survived, but there are still many other ways of dying. Of the 360,000 Northern Army soldiers who died in the war, about 220,000 died from chronic diarrhoea, dysentery, typhoid fever, pneumonia, tuberculosis, smallpox, malaria and measles.

In the early days of the war, the disorganized organization of army medical units exacerbated the deadly mix of wounds and illnesses. When Jonathan Letterman took over as medical director of the Podomac Legion Medical Center, the medical staff had no ambulances or specialized stretcher hands. To make matters worse, there is no uniform hierarchy in the treatment of the wounded, and doctors often lack critical supplies. Letterman knew the key to saving wounded soldiers was getting them timely help. His Plan for the Army of the Potomac required a convoy that would only be used to transport the wounded, and required each regiment to assign stretcher bearers who were not required to take on combat missions.

Letterman divides the treatment of the wounded into three phases: battlefield first aid stations as a stopgap measure, nearby mobile field hospitals as surgery and other emergency procedures, and further afield general hospitals as follow-up care. This simple three-tier system remains the blueprint for modern field medicine (the U.S. Mobile Army Surgical Hospital, known in the 1970 film Army Hospital Integrated Medical Services, followed by a television series that was the ultimate embodiment of the Army Field Hospital in the Letterman era). Finally, Letterman organized a reliable system that would provide surgeons with the medical equipment and supplies they needed.

Letterman's overhaul of the Potomac Legion Medical Corps continues to prove its worth after the Battle of Antitam. At the Battle of Gettysburg in southern Pennsylvania, on July 1-3, 1863, the new system was put to the greatest test. One of the most famous battles of the war involved more than 158,000 soldiers—some 83,000 northern soldiers led by General George G. Mead and 75,000 resistance troops under the command of General Robert E. Lee. The victory of the Confederate Army caused a staggering 51,000 casualties (23,000 Northern Army and 28,000 Confederates). Letterman's ambulance team dispatched 1,000 horse-drawn carriages, operated by 3,000 coachmen and stretcher handlers. Notably, medical personnel had cleared the wounded from the battlefield by July 4.

Six months after the Battle of Gettysburg, Letterman abruptly terminated his cooperation with the Army of the Potomac due to a political squabble. Fortunately for the average soldier, the changes that Letterman facilitated have persisted. In March 1864, the casualty management model of the Army of the Potomac was extended to the entire army.

In December 1864, Letterman resigned from the Army Board and moved to San Francisco, where he practiced medicine and won the post of coroner. In 1866, he published his memoirs of the Civil War, a medical memoir of the Army of the Potomac. Letterman died in March 1872 at the age of 48. In 1911, the Army Hospital in Presidio, San Francisco, was named after him. Letterman is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. His tombstone reads: "From 23 June 1862 to 30 December 1863, the medical director of the health organization of the Regiment of the Army of the Potomac, who brought order and efficiency to the medical service, he was the founder of the modern method of medical organization in the army."

From a human perspective, Letterman did much more than that simple epitaph suggests. He has touched thousands of lives, from his own time all the way to the present. The battlefield is littered with monuments to the warriors, but few have noticed the heroic achievements of those who worked to save lives rather than sacrifice them. These doctors who treated the fallen soldiers always did everything they could to alleviate the suffering of the soldiers. In this worthwhile endeavor, they are no better than Jonathan Letterman was a better ally.