Reporter | Dong Ziqi

Edit | Yellow Moon

1

When life is at an impasse, doing nothing becomes an effective way of self-fulfillment. In Not Working, Josh Cohen, a psychoanalyst and professor of literature at the University of London, divides inertia into four categories: burnout, slob, daydreamer, and slacker.

The weary begin to be driven to action by blind impulses, but they are caught off guard and sink into the ground, belonging to the Japanese family. Sloths are active in the children's cartoons we are familiar with, they are Snoopy, Garfield, openly lazy to do, shamelessly refuse to work. Compared with the first two pulled by geocentric gravity, daydreamers and idlers have more impulses to detach from gravity and transcend reality – daydreamers lock their doors and refuse to respond to social reality; idlers withdraw from regular life and live at their own pace. Each of these four categories of people has its own characteristics and overlaps with each other, but all confirm the significance of stopping from the "inertia of perpetual motion."

Use tiredness as a starting point

The Higuya people, who are seen as weary, may make us pay attention to the current social and cultural ills, and the author quotes Saito Kan's "Hikuju People" as a silent protest and desperate expression of individual differences and personal dissent that have been suppressed. People reflect on the situation through the Jingju people: Does the current society want to turn everyone into the Jingju people? While most people's symptoms aren't as extreme, there's a secret corner deep inside that resonates with the Hibiki.

On the one hand, people are frustrated by the lazy worms who enjoy their success, and on the other hand, many of them have become classic literary figures: Goncharov's Oblomov writes about a special figure who has been lying in the bed for many years, wrapping himself in a cocoon, who refuses the advice of friends to get up and embrace life, and regards lying as the normal state of life. Oblomov, who was lying in bed for a long time, also became a famous representative of the "lying flat school". Bernd Brenner, who defended Lying Flat, said that every era had its own Oblomov — he was lazy and even superfluous, but there was still a trace of sympathy for his eccentricities.

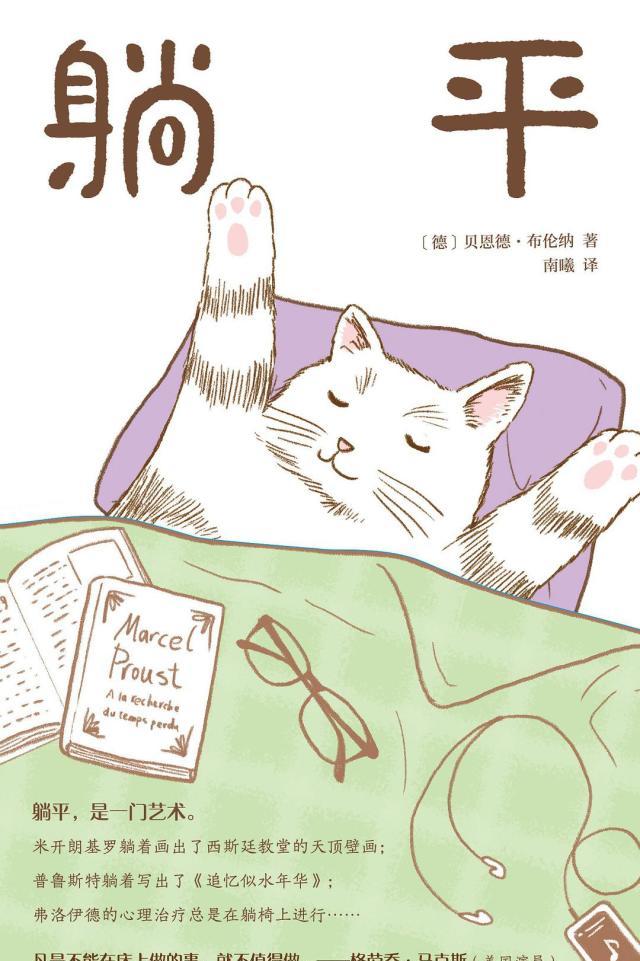

"Lying Flat"

Bernd Brenner by Nanxi translation

New Classics South Seas Publishing Company 2021

Diderot's Ramo is another famous slacker. In the novel "Ramo's Nephew", Rama adheres to the principle of happiness first, rather than hard work and self-blame, he shamelessly declares that he wants to eat delicious food, sleep in a spring soft bed, and lead to the peaceful end of life.

Daydreamers seem to be deserters of life, but they are extremely creative, creating their own reality with infinite possibilities. The American poet Emily Dickinson retreated into her bedroom, not to a state of listless rest, but to transcend earthly traditions of law by retreating.

As for the idlers, they are cold, suspicious, follow the rhythm of the self, refuse action and clear goals, and thus retain their individuality. In resisting dogmatic and religious fanaticism, and in being cautious about opinion leaders on social media, apathy and paranoia have become virtues. Josie Cohen himself is one of the idlers. When he was a doctoral student, he was confused by the lack of goals and nothing to do, and later found that his curiosity was not in harmony with a fixed work arrangement, and that work efficiency was not spurred by self-discipline, but stimulated by non-discipline, so he should not be anxious about wasting time and money.

Cover of the English edition of "Want to Do Anything, Don't Want to Do Anything" and author Josie Cohen

"I read, think, write, sometimes on a whim, sometimes all night, sometimes with a quarter of an hour of coffee breaks, sometimes as a natural result of a week of emptying." Between effort and letting nature take its course, Cohen chose the latter. He argues that effort can instead limit the development of creativity, and that "the patterns of observation, listening, and thinking that we strive to carefully take us to the unknown are almost impossible." This may have something in common with Jeff Dale, who has also been angry and burnout for a long time, waiting for inspiration to come by — Dale says that the great moments in hindsight are echoes of days of doing nothing.

Deprived of simplicity and laziness

One of the questions Josie Cohen pondered was, why is it so hard to stop? "Forced optimism" is one of the characteristics of his thinking. Nowadays, "active", "responsible" and "proactive voices" are filled with advertisements and chicken soup for the soul, and even the person receiving the job search allowance must prove that he has made a positive effort, no matter how frustrated the job seeker is, he must adapt himself to this set of "smiling and aggressive red tape". And this culture has led to apathy among the masses, who, even if they feel a loss of meaning and desire, dare not stand up against the condemnation of those who are not active enough.

In today's society, where we need to constantly choose, take sides, participate in, and make trade-offs, people are overstimulated to the point of neurasthenia. "Everyone can be who he wants to be" caused intense restlessness. In Worries, Francis O'Gorman has shown that contemporary market economies shape the spirit of choice, that society encourages people to actively choose and even control their looks and temper (with the help of plastic surgery and temper management courses), and that the consequence is that the selector needs to bear the burden of success or failure, and that free choice breeds more guilt and self-blame—self-criticism replaces social criticism. Cohen once met such a patient, "you can do anything you want" was injected into the patient's heart, becoming an internal appeal that made her scratch her heart.

Worry: A Literary and Cultural History

Translated by Francis O'Gorman by Zhang Xueying

Xinmin Says Guangxi Normal University Press, 2021

Attachment to actions and goals also shapes people's lives, and when people insist on planning their actions with a dense schedule, they deprive them of "the purest experience, that is, the experience of being." With regard to existence, he explained, the busyness of the body and mind deepens inertia like immutable, the unknown and the outside can not be intruded, and existence is the cure for this inertia. The author cites Oscar Wilde as opposed to the activists, calling fanatical action only a clever cover for its own emptiness, and that action is a refuge for those who have nothing to do. The concept of vocation transforms work from a practical means of subsistence to a sacred end, and the belief that man's essence is work also means that in order to perform his duties, people need to adapt to rhythms that are not their own, and suppress any unrelated and useless impulses.

"That means being in a waterlogging convoy or waiting for a delayed train on a crowded platform, it means trying to fit the rhythm of the keyboard and cash register, it means getting things done within tight deadlines and suppressing any urge to take a nap or take a walk." We don't like labor because it allows us to live in ways that don't belong to us. ”

This also ensures a culture that is never able to focus, josh Cohen writes, where the space for immobility and wasted time disappears, the true "shutdown" of things disappears, every moment of human life feels like punching in, and doing nothing and doing nothing can lead to panic.

Walking also becomes an act of non-work and anti-work, because man should work for the sake of production, and walking is a time of dead silence without wealth. Even advocating "slow life" is for the sake of the idea of man as an instrumental creature driving the task, slowing down, not for the sake of the soaring productivity of the brakes, but for the sake of healthier bodies and clear thoughts, in order to become better employees, parents and lovers - that is, useful.

But is it really that important to use effectively? As Thoreau, who loved to wander rather than toil and make money, had long written, as an adult, man seems to be given a special and petty use, carrying out a certain plan throughout his life, and thus not looking around to grasp the various things of life and life. What Josie Cohen misses most is also his childhood when he was sick off at home and lay on a soft and warm couch and watched tv aimlessly, he didn't care what the TV played, he just missed "being reduced to the most basic satisfaction of the body". He believes that people were lazy in childhood, like Snoopy and Garfield in the cartoon, but reluctantly adapted to the rules of reality in their growth, and the lazy fairy tale disappeared.

"I want to do everything, I don't want to do anything"

[English] Josie Cohen by Liu Han translated

Spring Tide CITIC Publishing Group 2022