--Based on the perspective of public service

After the completion of poverty alleviation, rural revitalization will be a more difficult task facing China. Different from the analysis of mainstream economics, the article argues that the reason for the decline of the countryside is not the lack of autonomy of farmers in land transactions, but the lack of infrastructure and public services caused by the disintegration of rural collective organizations, the fragmentation of land property rights, and the shielding of capital by the collective economy are the root causes of the development gap between urban and rural areas. Returning to the classical cost function, the market is regarded as a monistic whole composed of the public and the individual, and the symbiotic relationship between public wealth and private wealth can be analyzed to find that the institutional potential of collective ownership has not been fully tapped. The direction of the future reform of the rural system should be to transform the village collective organization into a modern organization that can capture all kinds of capital, and it will undertake asset-heavy public services, so that farmers can operate asset-light. Since there is an inherent conflict between the production model of smallholder farmers and the public service collective, it is necessary to separate the ownership and use of arable land, rebuild the interest relationship between the state and farmers, and then build an agricultural platform on this basis to complete the capitalization of agriculture. Whether public services have been improved and whether sufficient cash flow can be created independently is an important criterion for testing rural revitalization, so it is necessary to try to design price-based policy tools, explore diversified operating models, and strive to promote capital to go to the countryside.

Since the reform and opening up, the understanding of China's rural problems has been blamed on the collective ownership system implemented in the era of the planned economy. This judgment was further supported by the great success of rural reforms in the 1980s, with the household contract responsibility system at its core. Since then, almost all rural reforms have taken the weakening of the collective and the strengthening of the individual as the main direction of institutional improvement. By returning to the classical cost function and introducing fixed costs, this paper explains the symbiotic relationship between public wealth and private wealth, and then proposes that the decline in the supply capacity of public services caused by the disintegration of grass-roots collective organizations is the main reason for the current rural problems and the main bottleneck restricting future rural development. China's rural revitalization must begin with the reconstruction of rural public services.

First, the source of the problem

Wealth is composed of two parts: public wealth and private wealth, and the so-called public wealth mainly refers to various public goods (services) provided by the government. Since public services have a great impact on the cost of private wealth and determine the price of rural assets to a considerable extent, the level of public services basically determines the richness of a village.

1. Neglected premises

Historically, public services in traditional Chinese rural areas were provided through autonomy through the bond of clans and squires, which determined that rural public services were primary and low-level. The people's commune system provides rural areas with heavy assets with means of production (especially farmland irrigation infrastructure) as the core, and the level of related public services has been greatly improved. After the reform and opening up, the household contract responsibility system has made the family become an independent wealth unit again, and this reform has greatly stimulated the production enthusiasm of the labor force, the heavy assets formed in the period of collective ownership have been instantly revitalized, and the long-stagnant agricultural production has grown by leaps and bounds. It can be said that without the public service stock and dividends created by the collective economy, compared with other developing countries that have already adopted the private ownership economy, the reform effect of implementing the household contract responsibility system in China will not be fundamentally different.

2. Dissolution of public services

At the beginning of the implementation of the household contract responsibility system, the collective economy did not completely disintegrate, and the public services in the rural areas were mainly maintained by levying "three mentions and five unifications" from the villagers. In 2006, while exempting agricultural taxes, the "three mentions and five unifications" were abolished at the same time, and the contractual relationship between cultivated land owners and the state that had been implied for thousands of years disappeared, landowners no longer had farming obligations to the state, and cultivated land was arbitrarily diverted or even abandoned; the public services originally supported by taxes and fees quickly disintegrated, and the decline of collective economic relations caused the original interpersonal relations of mutual assistance and sharing in the countryside to disintegrate, and the autonomous public services that had long existed disappeared one after another As productive public goods such as farmland infrastructure are gradually depreciated, agriculture will be forced to return to traditional farming, and as costs continue to increase, agricultural production will gradually degenerate into economic activities with no commercial value, which in turn will lead to a further decline in the number of agricultural workers, and the deterioration of living public services will exacerbate this trend. In the face of rural decline, the government began to gradually take over some rural public services, but this practice of using industry to feed agriculture has led to a rapid decline in the autonomy of rural public services and the further loss of related mechanisms.

3. Property rights fragmentation and capital shielding

Another reason for the disintegration of public services is the rural land contracting system implemented in the 1980s with the basic content of "dividing the land into households and remaining unchanged for thirty years", coupled with the traditional Chinese average inheritance system, which has continuously fragmented the property rights of homesteads and farmland in rural China. This will not only greatly reduce the collective action capacity of village-level communities, resulting in a rapid rise in the institutional cost of public service delivery, but also once the growth rate of assets (mainly arable land in rural areas) is lower than the growth rate of population, it will lead to a continuous decline in per capita capital, making it inevitable that the countryside will be caught up in the infighting.

Since the original members who left the village collective could not transfer and realize the collective economic share they owned, the newly joined members of the village collective naturally could not obtain the collective share guaranteed by law. As far as investment is concerned, unless the investor is a member of the village, he may be at risk that the property rights are not protected by law, and the original collective members use their collective identity to have almost no risk of default, and this asymmetry leads to the extremely high cost of mutual trust between the capital input party and the capital receiver. Because long-term returns are difficult to obtain effective legal protection, it hinders the entry of external capital, intangible capital

Barriers prevent village collectives with responsibility for providing rural public services from performing their duties effectively. However, the probability of appearing among the members of the village who have the ability to operate capital and can get the support of the whole village is not high, which makes the rural revitalization show a greater contingency.

Second, theoretical reconstruction

Recently, the central government has revived the need to strengthen the collective economy, but due to the lack of corresponding theoretical support, more people regard the strengthening of the collective economy in rural areas as a step backwards in reform. Actual poverty often stems from theoretical poverty, and to achieve rural revitalization, we must start from theoretical reconstruction.

1. Poverty in traditional theories

In the 1980s, China's implementation of the household contract responsibility system characterized by "dividing the land into households" achieved world-renowned success, and was regarded as a classic case of privatization of property rights in neoliberal economics and promoted. In the view of mainstream economics, the lack of effective incentives for families and even individuals is the root cause of poverty. Only by thoroughly reforming collective ownership and solving the incentive problem of micro subjects can it be possible for the market to "play a decisive role" and the rural problem will be solved, so privatization of property rights is regarded as the only way to achieve this goal.

This understanding also determines the direction of the formulation of the "three rural policies" - to give up profits and decentralization to farmers, that is, to further strengthen the household contract responsibility system, reduce taxes and burdens, confirm land rights, and let the market play a greater role... But similar reforms, far from allowing the countryside to reproduce the prosperity at the beginning of the reforms, have plunged them into a continuous withering. The agricultural sector, which once contributed the most to China's economy, has gradually become a heavy financial burden. Setbacks in practice have led many to re-examine the collective economy, and reality suggests that viewing private and public ownership, planning and market as dualistic opposites may not be the right paradigm. To achieve rural revitalization, it is first necessary to establish a theoretical analysis framework completely different from neoclassical economics.

2. Heavy assets and fixed costs

According to the cost function of classical economics, the production cost of agriculture consists of two parts: fixed cost and variable cost. Unless the natural conditions are blessed, agriculture in most areas requires large fixed costs centered on irrigation, electricity, roads, and even health care and education, which are heavy assets of the rural economy. As the commodity economy continues to develop, transaction information has become a new fixed cost of agricultural production. In the 1980s, the state abolished the unified purchase and marketing, which on the one hand gave farmers greater operational autonomy, but on the other hand, it also increased the market risk of agricultural production.

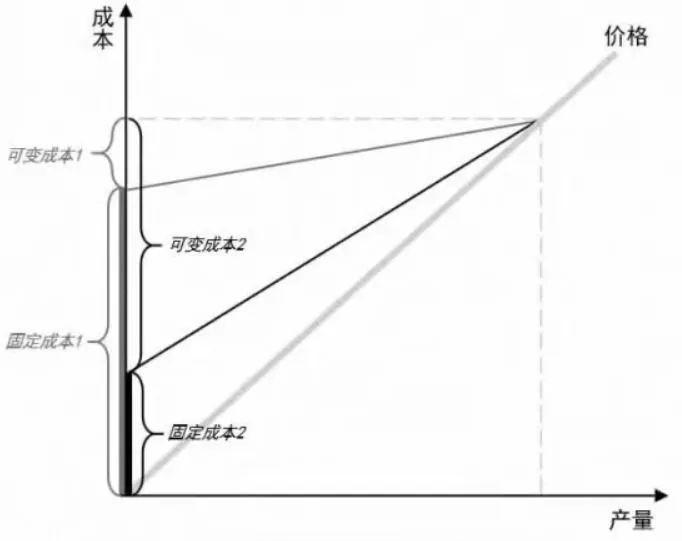

High fixed costs are the biggest obstacle to rural economic development, and it is clear that this part of the cost is difficult for smallholder economies to afford. Since infrastructure investment has typical economies of scale, the establishment of collective organizations and the provision of infrastructure and public services by them are necessary conditions for the upgrading of rural industries. In other words, only when collective organizations provide heavy assets for the rural economy can family farmers achieve asset-light operations. Since there is a dissipation relationship between fixed costs and variable costs under the same yield, see the chart below, the higher the proportion of collective assets, the more developed public services, and the smaller the minimum asset size (such as arable land) required for household economic operation.

3. One-dollar market structure

Once fixed costs and variable costs are introduced, it will be found that perfect competition described by mainstream economics is a "hypothetical" market composed of countless independent individuals with zero fixed costs, and the government that provides public services is regarded as an exogenous variable of the market, and the relationship between the two is antithetical. But the complete structure of the real market consists of a combination of the public sector, which provides collectively heavy assets, and the private sector, which is engaged in the production of private products. According to new research advances, under this market structure, the public services provided by the government are not only not superfluous, but necessary. Only under the premise of providing a high level of public service can individual operating costs be reduced and thus win the competition.

Traditional economic theory puts collective consumption (production) and private consumption (production) into a single dimension, and the collective action of the public part must be planned and monopolized; while the individual part, on the contrary, faces an unknown market, needs continuous independent innovation, so that satisfying one party's policies must be at the expense of the other party's interests. Contradictory needs lead to contradictory policies, and supportive theories can be found from each perspective. In this "dualistic" market structure, the organization of production can only choose between the collective economy and the private economy, and if the collective economy does not work in practice, then the private economy must be correct, and vice versa.

Once the discussion of collective action and individual action is perfected from the "binary opposition" under the traditional economic theory of "individual" to the "unity" of "public", the provision of public services and the provision of private goods are not either-or, but can be symbiotic - the higher the level of supply of public goods, the more developed the private economy. Applied to the rural economy, that is, collective organizations that provide public services and private organizations engaged in individual production are two sides of the market, and the direction of institutional design should be to strive to change the relationship between the collective and the individual from a trade-off to symbiosis.

Third, the direction of the system

To achieve rural revitalization, we must rebuild the market conceptually. The small-scale peasant economy is the "end" of agriculture, and public services are the "foundation" of agriculture.

Land annexation is a necessary condition for improving public services, which requires the redesign of land systems and financing schemes.

1. Rebuild the market

A "unified" market is composed of "stage" and "actors". In the era of the small-scale peasant economy, there are only "actors" (families) but no "stage" (infrastructure), and the high cost of production makes it impossible for production activities to produce the necessary surplus; in the era of collective economy, there is only "stage" but no "actor", and "stage" as capital cannot be transformed into benefits. The direction of the future reform of the rural system is neither to completely privatize and throw isolated peasant households into the "market"; nor is it to return to the collective economy and once again deprive peasant households of their autonomy in operation. Rather, it is to construct a public service and individual economic sharing mechanism to restore grass-roots public services so that every farmer can quickly respond to the signal of market demand at the lowest cost.

In view of the fact that public services are the common heavy assets of all individuals, in the face of the huge scale of individual agriculture in developed countries, the basic public services in rural China can only be far superior to the former, so that China's small-scale family farming can gain market competitiveness comparable to large-scale farm operations in Europe and the United States. In contrast, the smallholder economies of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan survive not because of private ownership of land, but because collective organizations such as "agricultural cooperatives" provide perfect public services.

2. Land annexation and conversion

Public services are a collection of all weight assets with significant economies of scale. In the process of improving the level of public services, land annexation will inevitably be accompanied by land annexation, so it is necessary to prevent the resulting division between the rich and the poor. For the choice of agricultural production methods, the dilemma of equal wealth and high efficiency is a dilemma.

Despite its vast territory, China's rural household economy is smaller in size (measured by contracted land) than other East Asian economies. Obviously, relying on traditional agriculture alone cannot bring enough cash flow to support rural public services, and even with "collectives" such as people's communes, it is difficult to complete the accumulation of heavy assets required for agriculture. As a result, if rural areas are to have access to capital to support high-level public services, they will have to rely on the non-farming of farmland. This leads to an absurd result – if the countryside is to be revitalized, agriculture must be eliminated. If peasants are simply given greater land rights (such as "farmland into the market" and "same rights in the same land"), the result must be that farmland is constantly being converted into more productive non-agricultural land, which is obviously contrary to the original intention of rural reform, and the greater the power of the "landlords", the faster agriculture will disappear. The only way to maintain the autonomy of the individual small-scale peasant economy and to provide collective public services through economies of scale is to split the land property rights and adapt them to the two contradictory demands of land property rights adjustment, namely, the concentration of collective requirements and the dispersion of individual requirements.

3. Separation of land rights

For thousands of years, China has continued the tradition of "granting land" by the state to maintain the responsibility of landowners to the state. The abolition of the agricultural tax in 2006 severed the relationship of responsibility-obligation between farmers and the state, and the state lost the right to intervene in the qualifications of agricultural practitioners and the disposal of means of production (especially land). If the State is to sustain agricultural development, it cannot rely on the "voluntary" choices of the market, but must restore its rights and obligations as a rural public service provider on the basis of the "separation of powers" of agricultural land, and restore and preserve the link between the State and the users of arable land by designing new land ownership relations.

The specific operation is to learn from the ownership structure of "field bottom" and "field surface" that have appeared in Chinese history, and split the ownership of cultivated land ("field bottom") and the right to use ("field surface") - the whole people own the "field bottom" of all cultivated land, and the state as the representative of the whole people is the ultimate owner of the "field bottom", authorizing organizations at different levels (local governments, social enterprises, agricultural cooperatives, Internet platforms or village collectives, etc.) to hold on behalf of them, and the nominee holder is equivalent to the "landlord" and is responsible for holding cultivated land assets for a long time. The use of the land may be determined, and at the same time it has the obligation to continuously improve the public services attached to the land and ensure its continuous preservation and appreciation, the nominee holder may subcontract the land to the members of the collective in accordance with the requirements of the State, the rent shall be divided between the State and the "landlord", and accordingly, the two shall share the public services of the village collective (equivalent to the power of the first level of government), and all the increase or decrease of arable land and the change of use must be licensed and registered by the State; the family farmer is equivalent to the former "sharecropper", under the condition of satisfying the basic requirements of the "landlord" ( Protect arable land and pay for public services), freely engage in production, collective members can cultivate their own land, can also transfer "tenant rights" to other collective members, and the tenants must meet the basic requirements and pay rent to the state (collective). They can also transfer tenant rights in the land market at any time, vote with their feet between different landlords (village collectives), and village collectives attract and retain tenant farmers (families) by improving public services, and the "field bottom" and "field surface" correspond to the capital market and the labor market respectively, and trade freely in their respective markets – the former can be continuously merged according to the requirements of economies of scale; the latter can be continuously subdivided as the level of public services improves.

By not having to burden the heavy assets of agricultural investment, sharecropper contracts can be very short (even on a harvest cycle), and asset-lightness makes sharecroppers unfettered foot looser. With the accumulation of capital and the improvement of the level of public services, more asset-light employment opportunities will appear in rural areas. Such as specialized wheat customers, sowing, fertilization, logistics, etc., to provide seasonal jobs similar to industrial workers. With the increase in the density of agricultural technology, the labor intensity gradually declined, and agriculture became a more attractive employment industry for young people.

4. Capitalization of agriculture

The grain production link itself cannot create enough cash flow, and only by linking the industrial chain of agriculture and urban division of labor (catering, tourism, green, leisure, etc.) can the capital entering the countryside get enough returns from agricultural investment. The natural closure of the current village collective system makes it difficult to integrate into the high-value industrial chain. The most important thing to transform rural collective organizations in accordance with modern enterprise standards is to do so

Enable traditional rural assets to obtain a legal capital interface. To achieve this goal, it is necessary to capitalize (equity) separately on the basis of the separation of rural land and land rights - open up the capital market, so that urban capital can obtain the right to operate the village through the acquisition of collective shares under the premise of meeting the national policy objectives; individuals and enterprises can enter the village collective through the purchase of equity, and enjoy the share of homestead and cultivated land, and share the village collective public services and the dividends of the corresponding shares. This policy design ensures that capital can enter agriculture, thereby connecting the rural economy to the high-value division of labor chain, while avoiding the loss of the property rights of the owners of the "field surface" caused by the capitalization of the "field bottom" (such as land annexation). After the upgrading and transformation of the rural collective ownership system, through the opening of the "field bottom" rights and interests and the introduction of state and social capital, the upgrading of agricultural infrastructure and the reconstruction of rural public services have been completed.

This means that the institutional design direction of rural reform should not be to disintegrate collective property rights into smaller private property rights, but to promote the transformation of collective property rights into a modern property rights structure, rebuild public services in rural areas, and complete the heavy asset investment and construction necessary for agricultural development. The reform of the rural system should abandon the dogma criticizing land privatization, establish a strong and open collective platform, complete the capitalization of agriculture through access to the non-agricultural industrial chain, and put the establishment of a rural self-"hematopoietic" mechanism at the core of rural revitalization.

5. Revitalization criteria and exit paths

There are three criteria for measuring whether rural revitalization has been achieved: first, whether the owners of the "field" (farmers) can independently generate positive cash flow; second, whether the cash flow obtained by the owners of the "field" (collective) is sufficient to cover the public service expenditure in the countryside; and third, whether the rural and urban areas have the same cost performance as far as public services are concerned. The objectives of all policies are to reduce the fixed cost of agriculture and increase the per capita cash flow income of the countryside. Every investment and policy to support rural areas must be based on whether public services have been increased and whether cash flow income can be created as the standard, and all poverty alleviation that cannot bring new cash flow will be difficult to sustain once it leaves the subsidy.

For those villages that really cannot be revitalized, as long as these villages can bring ecological and natural capital appreciation at a larger scale (regional and national levels) and generate more cash flow, the state can help farmers in the corresponding areas to withdraw from the villages that cannot participate in the modern economic division of labor through redemption, and restore agricultural resources to other natural resources of higher value (such as returning farmland to forests).

Fourth, revitalization measures

Following the institutional direction of the above analysis, this paper believes that the following specific measures should be taken for rural revitalization.

1. Design price-based policy tools

In the stage of rapid urbanization, it is unrealistic to demand that arable land is not diverted at all. In the era of underdeveloped monetary economy, most of the tools for farmland protection were based on various mandatory administrative "red lines"; as the monetary economy replaced the regulated economy, administrative-based policy tools gradually failed, and the policy "red lines" were constantly broken, and it was necessary to design price tools based on monetary economy. An effective way is to allow local governments to levy "non-fiscal policy fees" that do not aim at fiscal revenue increases – taxing behaviors that do not meet policy objectives, and rewarding the full amount of income earned to behaviors that meet policy objectives, thereby achieving incentive horizontal transfers between different entities.

Land can be divided into two categories: construction land and non-construction land (mainly agricultural and ecological land). The former pays the construction land use fee every year according to different purposes, and the relevant income is used to establish a land conservation fund; the latter obtains the non-construction land compensation according to the area and effect evaluation every year according to different standards. The new construction land indicators are in the form of public auctions, and villages that promise that the villages with a higher amount of construction land use funds every year have priority in obtaining construction land indicators in the next year. Compared with the land ticket system, the system design of the compensatory use of construction land indicators can transform one-time capital into continuous cash flow, bring additional income to the original low-value farmland, increase the opportunity cost of farmland conversion, and ensure that the new construction land can generate corresponding cash flow. For farmers, protecting arable land becomes a valuable act; for governments, the market value of arable land can be affected by raising or lowering the standard of arable land compensation.

2. Innovate rural operating models

China's territory is vast, regional development is unbalanced, and the path of rural collective property rights formation is bound to be diverse. Separating "field bottom" and "field surface", there are basically two paths: one path is bottom-up, similar to the owner's choice of property company, the villagers who have the right to contract ("field noodles") choose the best provider of public services; the other path is from top to bottom, the state takes back the land ownership ("field bottom"), and it is in the market to select the best public service provider for the villagers.

The above two paths can evolve into a kaleidoscopic market form, and a large number of modern rural operating models have emerged. For example, rural assets can be quantified, and investors with modern business models can be introduced under the premise of fully protecting the interests of indigenous people; the government can also outsource the business of providing public services to rural areas to social enterprises, and allow some enterprise taxes to be transferred to village collectives to cover the cash flow expenditure of maintaining the operation of public services; in addition, e-commerce platforms and large logistics enterprises can also be transformed into public service providers such as cooperatives and agricultural cooperatives, providing farmers with full-process services from seed selection, fertilization, sowing, harvesting to acquisition. Shorten the entry of individual residents into the final market, reduce the risk and cost of individual price finding. Different rural public service providers compete in the market, and farmers can choose the public service consumption mode that best suits local characteristics. In rural areas where public service providers cannot be found in the market, the government can obtain shares through the land conservation fund and directly provide infrastructure and public services as "landlords", while farmers are transformed into "sharecroppers" of the government.

3. Promote capital to go to the countryside

(1) Collective capital

The "collective" formed by the recollectivization of the countryside is not a narrow "village collective" with the villagers as the main body, but a continuous genealogy composed of a series of organizations that provide public goods from the village collective to the agricultural cooperative, from the platform enterprise to the agricultural cooperative, and from the local government to the central government. Among them, the most critical is the village collective organization authorized by the Constitution. After the reform, the "field bottom" of the village collective can be a mixed property rights combination and can be transferred in the capital market. The property rights of different collectives can be merged, or they can go to the market to "attract investment" and find operators who can provide high-quality public services.

(2) Industrial capital

Social enterprises can obtain partial ownership of village collectives through competitive land markets and introduce their non-agricultural business into village collectives (such as tourism and pensions); they can also purchase assets related to their business (such as scenery and cultural relics) and revitalize rural assets (such as homestays and tourism) under the premise of satisfying relevant national policies (such as farmland protection), so as to open up the connection between rural and urban non-agricultural industries.

The characteristics of high dispersion and low return of production factors determine that the provision of public services in rural areas must be high cost and low efficiency, and it is difficult to compete with urban public services. It is difficult for industrial capital to pursue efficiency as the protagonist of rural public services, and if it relies only on village collectives, it can only provide a limited level of basic public services, and it is difficult to reach the standard of "revitalization". The reason why the Japanese Agricultural Cooperatives can provide comprehensive and diverse professional services for small farmers is closely related to the government's permission to monopolize the cooperatives in the financial and food circulation fields. Therefore, the central government can also try to transform the current collective economy into a part of the market-oriented agricultural cooperatives through finance (low interest rates) and finance (subsidies) to provide paid services for the rural areas.

(3) State capital

At present, most of the state capital enters the countryside in the form of subsidies through financial channels, and the upper limit of the financial budget determines the level of support for rural public services. Relying on financial subsidies to provide rural public services, the result must be "blood transfusion", which eventually leads to the loss of rural self-"hematopoietic" function. Finance not only plays a small role in rural capital, but because the operating rules of commercial banks determine that finance will even reverse the extraction of rural capital. For now, the central bank is basically a bystander role in rural revitalization. Based on this, a direction that can be explored in the future is to change the channel for the central bank to issue base currency through commercial banks, and try to inject base money directly into the rural public service field. To this end, first of all, the establishment of a national rural revitalization fund independent of finance. Second, the central bank issued base currency to purchase the rural revitalization fund on a large scale. The State Rural Fund uses these low-interest, high-energy currencies to purchase arable land (field floors), transform farmland infrastructure, and establish agricultural public service platforms. Finally, these assets attached to high-level public services are used as collateral for base currency issuance, and the interest-free money that enters the countryside and then enters the bank's savings system, becoming the source of access to the base currency for commercial banks. In this process, the interest on the base currency originally attributed to the central bank was left in the field of rural public services, and the issuance of rmb was direct financing for rural public services.

V. Conclusion: The Fourth Revolution

After the completion of poverty alleviation, the more difficult task of rural revitalization is in front of us, especially in today's globalization, ensuring food security has risen to a national strategy, making rural revitalization more urgent. If farmers' poverty alleviation can be solved by policy means such as transfer payments, counterpart support, and special subsidies, rural revitalization must be based on their own sustainable endogenous wealth. "Blood transfusion" can help get rid of poverty, and "hematopoiesis" can be truly revitalized. The right policy must be based on the right answers to the question. In order to formulate a correct rural revitalization strategy, it is necessary to give a correct explanation for the reasons for the loss of hematopoietic function of the rural economy.

If the agrarian reform is the first revolution in China's rural areas, the collectivization of the countryside and the people's communes are the second revolution in the countryside. The former passes

The subdivision of land solves the problem of incentives for landless workers, who try to provide rural public services without land annexation. Due to the inherent conflict between the production model of smallholder farmers and the collective provision of public services, the design of the relevant institutions for rural reform is doomed to face a dilemma. After the reform and opening up, the third rural reform with the household contract responsibility system as the core is essentially a return to the first revolution, solving the problem of lack of incentives brought about by collectivized production, experiencing the cycle of development, and public services have once again become the main problem in rural areas. In fact, the repeated land annexations and redistributions in China's history stem from the inherent conflict between the two goals mentioned above.

Today we propose once again that rural revitalization should not be a repeated jump between the first and second revolutions, but to create a fourth revolution that will solve the problem of small-scale peasant economy and public services at the same time. This requires a redesign of the property structure that is compatible with both goals, separating capital from labor, and reducing the high fixed costs inherent in smallholder economies by rebuilding rural public services. Unlike the background in which it was before, today's China has an unprecedented huge capital and advanced technology (especially communications and transportation), and is fully capable of establishing a developed public service system in the vast rural areas, so that smallholder production has a similar market competitiveness to large-scale industrial operations.

To complete the Fourth Rural Revolution, we must first break the superstition of privatization in traditional economics and establish a new theoretical framework in which the collective economy and the individual economy are no longer trade-offs, but symbiotic. The key to establishing this framework is to split land rights into ownership (the bottom of the field) and the right to use (the surface of the field), and enter the circulation of capital and labor markets according to different rules. In this way, the original "flat" rural structure can be expanded into a "three-dimensional" rural structure, and the originally incompatible collective power and individual rights can coexist in a new framework.

The future rural revitalization policy is neither to return to the previous collective economy, nor to simply maintain the current household co-production contract, but to rebuild a new modern collective economy on the basis of maintaining the existing system. A strong, multi-level network of public services in the countryside was established by transforming the original village collective organization into a modern organization capable of capturing all kinds of capital. Once the countryside can obtain public services close to the city, agriculture can operate as lightly as other urban industries, and the entry of collective land into the market becomes a false proposition, because the countryside at this time is already a "city".

(The author Is Yanjing Zhao, a double-appointed professor at the School of Architecture and Civil Engineering/School of Economics, Xiamen University, and an associate professor at the School of Economics, Xiamen University; Rural Discoveries are transferred from: Social Science Front, No. 1, 2022)