When it comes to traditional Japanese culture, many people always think of "samurai"; when it comes to samurai, the so-called "loyalty" is one of their proudest labels. In fact, the sheer number of samurai groups could themselves be seen as a miniature society, especially in a hierarchical society like Japan, where the class contradictions of such a miniature society would become more acute. We have the impression that samurai are united and tenacious, preferring to die, which is actually something that the Japanese can show when they promote their culture. Historically, the samurai group has actually done a lot of things, especially for the lower samurai, the so-called "Bushido spirit" is just lip service.

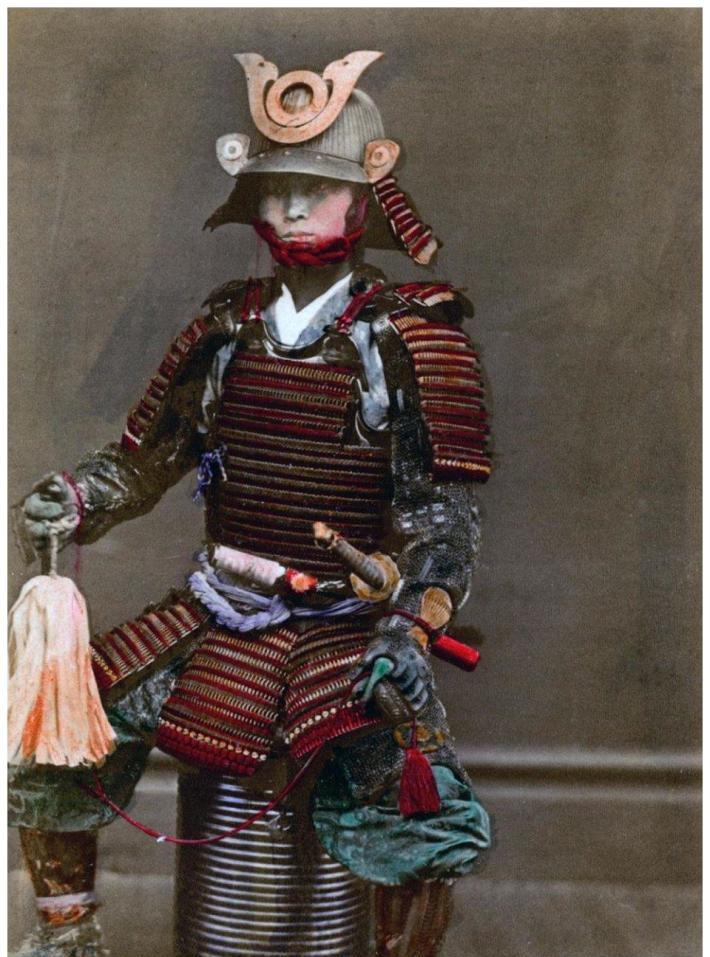

Samurai played a very special role in Japanese history, and there was a certain similarity between them and the Junker landlord class that gradually formed in Germany in the 16th century. Samurai can be divided into 12 ranks according to rank: Shoi Daimyō, Daimyo, Laozhong, Miyako, Daimyo, Kinō, Shōgun, Samurai Shogun, Ashikaga Shogun, Ashikaga- daimyō, Ashikaga-tou, and FootLight, among which the so-called "Shogun" was originally a temporary high-ranking military position set up during the Nara period of Japan to conquer the Ezo clans occupying eastern Honshu and Hokkaido; the yamen of the Shogun was called the "Shogunate". In 1192, genrai became the shogun of the Seiyi Dynasty and established the Kamakura shogunate, and princes and soldiers from all over the country heeded his call.

Initially a private force at best, the samurai were recognized by the court for repeatedly helping the court suppress rebellions, and gradually evolved into a social class. On the whole, the status of the samurai class in Japanese society does not seem to be low, in fact, the treatment of different levels of samurai can be described as a world of difference. First of all, the samurai were very concerned about their origins, and to put it simply, in Japan at that time, titles and social status were most likely inherited. The ancestors were nobles, so they were born with the title of nobility; if the peasants wanted to turn themselves into local lords, I am afraid that they would not be able to dream. The more prominent the samurai became, the greater the power they gained. There are often daimyoes who serve as both mayors and police chiefs, and even the commander of the local army.

Among the samurai there are very special people, who are called "flag books". During the Edo period, these samurai were direct vassals of the Tokugawa Army, and although they were both high and low, and some of them may be only 100 stone years old, they were all allowed to have their own armies, and they had great political freedom and special status in the shogunate group. Before the Meiji Restoration, Japan's population hovered around 30 million, with samurai accounting for 6.7 percent of it, while fewer than 4,000 Japanese samurai enjoyed privileges like kikimoto. That is to say, even the samurai, a group of higher social status, still cannot escape the chaos of "most of the resources are in the hands of a small number of people", and the lower samurai carry a face, in fact, they are more tired than the commoners.

Japanese samurai of the daimyo level often pay tens of thousands of tons of money, and the lower samurai can only be hungry. The lowest ashikaga samurai among the samurai is, to put it bluntly, a group of cannon fodder, "footlight", as the name suggests, is to run fast, on the battlefield, the pro-clan daimyōs wear armor but do not have to charge into battle, and the poorer foot light may not even have a saber, and can only hold a bamboo gun to fight with the enemy. In ancient China, ordinary soldiers still had the opportunity to be promoted to generals by virtue of their military achievements, and these foot-light samurai, although they held the title of "samurai", were born to be cannon fodder; even if they were born into a samurai family, their ranks were difficult to promote. As the saying goes, "Do not suffer from widowhood but from inequality", and it is not difficult to imagine that over time, these low-level samurai must be very depressed in their hearts.

It is worth mentioning that, like the scholar-doctor class in the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, everyone's sword may not be used to slash people for a lifetime, but to some extent, this is a symbol of their status and status, which must be left unavoidable. For the Japanese samurai, surnames and swords were things they had been promised early on, and some of the downcast grassroots samurai were so poor that they couldn't even mix swords, which was somewhat humiliating. These samurai have no place to go, so it often happens in Japan that if a ragged foot light samurai meets a merchant in brocade, if the merchant does not give way, the samurai will draw his sword and kill him. Many samurai who had just received their sabers ran out into the street to try their swords on the lowly commoners and tramps. Even if the officials received a report of investigation and learned that it was the samurai who had committed it, there was a good chance that such a case would not be resolved.

However, with the change of times, Japanese society had difficulty supporting a growing group of samurai, and the lives of middle- and lower-class samurai became more and more impoverished. Their situation was a bit like that of the Eight Banners disciples at the end of the Qing Dynasty, and many lower-class samurai had to temporarily lose their dignity, dressed neatly, with sabers hanging from their waists, and run to the countryside to cultivate the land. Some samurai who were accustomed to the days of clothes reaching out simply served as bodyguards for rich merchants or married the daughters of rich merchants as door-to-door sons-in-law. In this case, the big men at the top of the samurai class were very annoyed, believing that when the samurai were desperate, they should kill themselves by cutting themselves off, and should not abandon their dignity to eat soft food. As a result, many samurai who married into the magnates or served as bodyguards for wealthy merchants soon disappeared suddenly and never appeared again.

The poverty of the lower and middle-class samurai became an urgent problem to be solved, and the upper-class samurai turned a deaf ear to it, and the contradictions between them suddenly increased. On the one hand, the lower samurai were far less loyal than their fathers and grandfathers, and on the other hand, this directly affected the Japanese idea of "Shimokagami". In the 1860s, under the onslaught of Western capitalism, Japan embarked on a top-down reform of the shogunate. At the emperor's call, the fallen middle and lower-class samurai launched a fatal counterattack, and they rushed into the homes of the daimyo, plundering and slaughtering them. A large number of ronin mercenaries were used against the shogunate army, and interestingly, two groups of people with the same Bushido spirit fought to the death.

This reform movement soon became a good opportunity for the fallen samurai to vent their anger, and the shogunate that had ruled Japan for centuries was soon scorched by burning anger. Ironically, however, shortly after the fall of the shogunate, the Emperor decided to abolish the samurai class, and these unfortunate middle- and lower-class samurai served as cannon fodder at the end of their careers.