Richard Maeby

【Editor's Note】 Plantain, Summer Dry Grass, Pansy, Cow's Knee Chrysanthemum, Calendula, as well as Leaf Storage, Burdock, Three-pointed Tree... In your eyes, are they cute and pleasant idle flowers and weeds, or are they annoying agricultural hazards? Is it a symbol of life that burns endlessly in the wilderness and is born again in the spring breeze, or is it a troublemaker in the garden?

Richard Mabey, a British naturalist who has long explored the relationship between nature and culture, says the definition of weeds depends on the way humans perceive them. They live next to us, they are undesirable plants in nature, but if you look at history, fiction, poetry, drama and folktales, you will find that there is an intricate relationship between weeds and human civilization.

"The Story of Weeds" is such a book that "defends" weeds. Richard Mayby depicts a variety of weeds commonly found in human society, reviews their historical image and culture in literature, folklore, and explores why they are crudely labeled "useless, vulgar, and nasty" by humans.

"From the point of view of the development of farming, the natural world can be divided into two completely different camps, on the one hand the creatures that have been domesticated, controlled and multiplied for the benefit of mankind, and on the other hand the 'wild' creatures, who still live in their own territories and live more or less freely, and this simple and simple dichotomy collapses when the weeds appear.""

In Richard's eyes, weeds are boundary breakers, belonging minorities, and it is their "wild" intrusion that makes us know that life cannot always be so neat and spotless, while reminding us to look at plants from a grander space-time perspective, a non-anthropocentric perspective. Because such "wildness" is also the magic of natural creation.

With the permission of the publisher, this article excerpts several wonderful passages from the book (for convenience of reading, slightly deleted, subtitles are prepared by the editor), let us follow the author's text and explore the story of Shakespeare's pansies!

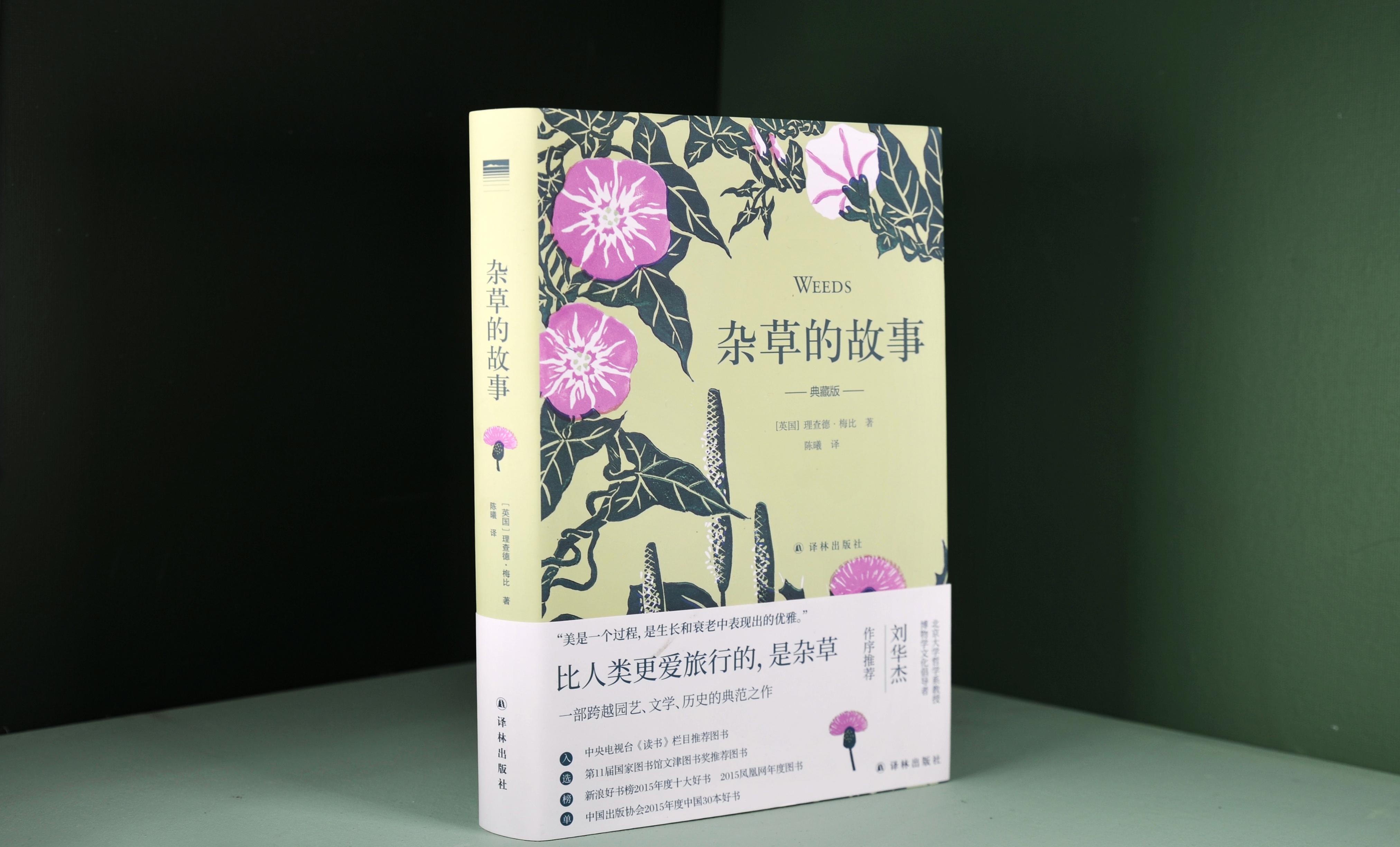

The Story of Weeds (Collector's Edition); [UK] Richard Mayby (author), Chen Xi (translation); August 2020; Translation Forest Press

Shakespeare and the Pansies of Love

Pansy is a common farmland weed that, taxonomically speaking, refers to two species of plants. One is viola tricolor, also known as the meditation flower, the pattern on the flowers is a combination of purple and yellow, which is more critical of the environment, and is distributed throughout the sandy and acidic soil of The United Kingdom. The other is viola arvensis,viola arvensis, which can be seen where there is arable land. The two plants are very different in size and color, but can be freely hybridized if they grow next to each other.

Although pansies are ubiquitous and interesting, they are not often used in medicine. Gerald believed they could treat pediatric convulsions, pruritus, and STDs. Calpeper agrees with this and adds something very personal to him: "This plant is typical of Saturn dominating plants, cold and sticky. The juice from the decoction of this plant and its flowers ... It is a special drug for the treatment of syphilis, and this herb is a powerful anti-sexually disease drug. This medicinal description is very different from the image of the pansy in people's minds — or it may be an example of homeopathy commonly used in the time of witch doctors: the weed that causes a disease is also the best medicine to treat it — because in the ordinary world, the pansy is a symbol of love. Since the Middle Ages at the latest, they have captivated human beings and triggered all kinds of romantic imaginations. In the traditional view, the villagers in the countryside will only see their practical value in the face of wild plants, and they may not have time to pay attention to other metaphysical things, or they cannot understand, but the romantic meaning of the rural weed pansies undoubtedly proves that this view is wrong.

Viola tricolor, also known as the meditation flower, has a pattern of purple and yellow on the flowers. Infographic

Wild viola arvensis (viola arvensis) with smaller flowers can be seen where there is arable land. Infographic

The reason why the pansies became symbols of love is not difficult to understand. Its flowers look like a face, with two high eyebrows, cheeks and a chin, and thin lines that look like eyes or laugh lines. Their common appearance is that there are several purple stripes on the dark milky white petals, but on closer inspection, each flower is different, as if it were randomly graffitied by a watercolor brush. Some flowers may wear dark eye masks, and some flowers may have purple beauty moles on their eyebrows or chins. I've also seen pansies with blue and purple stripes or spots, and occasionally all-purple flowers.

In France these contemplative little faces represent thinkers, so in the Middle Ages these flowers were called pensées (French, meaning "thoughts"), and later Englishized as pansy, or "pansies". But what people in the English-speaking area see from the pansies is two faces, and what these two people are doing is not at all as "advanced" as thinking—they are kissing, the petals on the sides are sweet lips, and the petals on the top are their hats. The pansies are commonly known in Somerset as "Kiss Me and Then Raise Your Head", and other common names include "Kiss Behind the Garden Gate", "Give Me a Kiss at the Garden Gate", "Give Me a Dragonfly Kiss", "Jump Up and Give Me a Kiss", and finally this romantic naming event is culminated in the Lincolnshire version of "Go to the Door to Meet Her and Kiss Her in the Underground Warehouse". But their more widely known name is "meditation flowers," and perhaps that's a sign of their usefulness: picking a small bouquet of pansies and giving them to a lover, giving them a sweet kiss through the intimacy of the flowers, and then the heart settles down.

Pansy has a more melancholy name in Warwickshire and the Midwest: Futile Love. The name may have arisen because the three petals on the lower side of the pansies can be seen as a woman caught between two lovers; the flower therefore represents a frustrating, fruitless, futile love. In the late 16th century, this allegory was accurately grasped by Warwickshire's most talented pride and written into a poetic story about plants.

Many of the pansy's names are associated with love. Infographic

Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream is probably the only drama in English literature that unfolds with the effect of a weed as its main story. The mandarin ducks in the forest are all caused by parker, the immortal king's subordinate, who squeezes the juices of the pansies on their eyelids while several of the protagonists are asleep. That way, when they wake up, they'll fall in love with the person they see for the first time.

Born and raised in Stratford-upon-Avon, Shakespeare is well versed in warwickshire's wildflowers and folktales. So he took it for granted that his audience must also be familiar with these plants, familiar with their common names and anecdotes. More than a hundred species of wild plants are mentioned in his work, and not surprisingly, most of them are very common plants, i.e. weeds.

Daisies, the "variegated" chrysanthemums mentioned in The Futility of Love, appear in at least four plays, and in The Humiliation of Lucreth, the daisies symbolize not only the purity of the virgin, but also the coming of spring:

Her other hand, hanging quietly and low by the edge of the bed,

Reflecting the pale green sheets, it looks white and delicate,

Like a April daisy, spitting out Fangfei on the grassland.

The daisy is also one of the components of the "strange garland" in the hands of the drowned Ophelia— "buttercup, nettle, daisy, and long-necked orchid" is the material for the garland, but the exact plant species referred to is still debated by botanists and critics. Shakespeare's audience should know the species and symbolism of these plants. The metaphor of nature was a common literary technique in the 16th century, and Shakespeare used this technique between puns, metaphors and winks, but these metaphors are only used in small areas and are too local to be understood by the audience. A mournful line in "Xin Bailin" reads: "Caizi Jiaowa returns to the spring soil / Just like the chimney sweeper." The metaphor sounds strange, but once you learn that the "chimney sweeper" in the Warwickshire dialect refers to a dandelion full of fluff after yellow flowers fall, the mystery is solved.

John Affle Millais' masterpiece Ophelia depicts the drowning of Rio Felia in Hamlet. "Buttercup, nettle, daisy and long-necked orchid" is the material for the garland in Ophelia's hand. Wikipedia Figures

"A Midsummer Night's Dream" is full of wonderful sentences containing botanical imagery. Much of the play takes place in a forest, which is set near Athens and is entirely a British landscape of British plants. However, this scenery is not completely arranged according to reality, and the protagonists of various plants come from different seasons and different growing places. Even the Arden Woods of Warwickshire can't be like the "fennel-in-bloom water beach" of the fairy Titenia, allowing you to pick a bouquet of fragrant, colorful but open flowers at any time.

The plot of A Midsummer Night's Dream seems very simple. The Athenian nobleman Ezis planned a grand wedding and wanted to marry his daughter Hermia and Dimetris. But she rejected the marriage because she loved another man named Lassander. So she fled into the forest, unaware that she was followed by her ghostly friend Helena, who secretly fell in love with Dimitris. But by the time they entered the forest, there was already conflict. The fairy king Aubrean quarreled with his fairy queen Titenia because she refused to give the little prince of India (stolen by the fairy queen's elves) to the fairy king as a waiter. Then the Weed Spell appears, and a little plant prank turns the little conflict into an uproar.

The 19th-century Scottish painter Joseph Noel Payton's The Quarrel Between Aubrand and Titenia is now in the Scottish Art Gallery. Wikipedia Figures

Being able to turn his own knowledge—such as folk knowledge about plants—into tools for dramatic plots is part of Shakespeare's extraordinary talent. If Shakespeare had ever gone to school to study drama, he would have learned this technique, a technique that elizabethans called "flexible turning." Add a clever narrative change to a superstitious statement, a rumor, a myth, or a true historical event, and the old story will be rejuvenated with new dramatic vitality. O'Brown's cronies, Parker, were also the plot movers who created "flexible turns." Parker's image comes from the good man Robin, who is mischievous and familiar with various plants. O'Brown, heartbroken by Tethynia's stubbornness, sends Parker to fetch the juice of a special plant and drop it on her eyelids while the queen is asleep, so that she will "fall madly in love" with the first creature she sees when she opens her eyes, but Parker is so naughty that she faints and drops this magical juice onto the eyelids of almost every frustrated lover wandering in the forest.

In this story, Shakespeare combines classic mythology, Central English folktales, and comedy. O'Brown called the pansy "a little flower of the West" and brought it to the audience from the far reaches of Athens. But the flower has been magically enchanted by one of Cupid's arrows, and its originally milky white color has also been "dyed purple by the trauma of love"—a description that faithfully reflects the color of the pansy and echoes the change of mulberry from white to blood-stained dark red in Ovid's Metamorphosis. Shakespeare called the pansies by the beautiful common name common to his hometown, "futile love", which is simply a plant tailored for the young people of Athens who suffer from love in the story. But Parker's squeeze of the sap of this plant into the eyelids of the hapless protagonist is not from any folktale, I think it should be Shakespeare's own creation, a perfect comedic technique.

O'Brown's cronies Parker dripped the juices of the pansy on Titenia's eyelids, so that she would "fall madly in love" with the first creature she saw when she opened her eyes. Grandmasgraphics diagram

If I had studied the symbolism of Shakespeare's plants myself, I would have studied it to this extent. But I was very fortunate to experience the spirit of a handful of professionals who studied this subject. In 2005, Greg Dolan, head of the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford, was preparing a new version of A Midsummer Night's Dream, and he invited me to work with him on the use of natural symbolism in the play, and to make material for the tv documentary that was being filmed at the same time. He was particularly interested in the description of Titenia's "water beach" and why the combination of plants has extraordinary charm:

I know of a beach where fennel is blooming,

Full of primrose and plump violets,

Rich honeysuckle, wild roses,

A fragrant brocade opened up in the sky,

Sometimes Titenia gets drunk in the flowers,

Soft Dance Qingge caressed her lowly to sleep.

This list of plants is really weird. Although these plants are wild (with the exception of musk rose), they are not weeds. But the differences between them are enough to ignore their small similarities. They include shrubs, climbing plants, and small clumps of perennials. They grow in different environments and flowering times are scattered at different times of the year.

Richard Dadd's (1817-1886) Titania Sleeping is now in the collection of the Louvre in Paris, France. Wikipedia Figures

This not only created difficulties in interpreting the script lines, but also created a problem for the entire project to operate, because Greg wanted to be able to film the discussion next to real plants. We carefully compared the different locations, weighed the distance and the advantages and disadvantages of the scenery, looked at the weather forecast over a long period of time, and finally selected a very scenic chalk hill in Chiltern, where I knew a lot, and I estimated that there we could photograph four of the six plants on Titenia's "water beach". We headed for the windmill of Tver, which was only a few days before Midsummer. "Primrose" (Primrose) and "Violet" (Viola) pre-bloom, but we still found the "Wild Rose of Qianze" (multi-flowered rose) and a piece of real "Fennel" (safflower thyme) blooming "Water Beach" (riverbank).

Safflower thyme Wikipedia Figure

We sat on the shore and looked out over the villages in the valley, savoring the alluring flora of Titenia. Red kites and eagles—just back in the hills—circle in updraft, a sight no different from the sky of Shakespeare's day. Below us was a wheat field surrounded by chalky soil, which looked like it was about to be lit by a large scarlet chimney next to it. The weed gets its name from its slender gray-green leaves, which look a lot like mist– fumus terrae, literally translated as "smoke of the earth." But here and now, the flowers are blooming, not at all like smoke, but like "embers of the earth."

Chimney Wikipedia Figure

Greg told me that Shakespeare," in his depiction of the corolla of the mad King Lear, mentioned the plant's common name, "ground tobacco": "Singing loudly, its head is covered with foul-smelling ground tobacco, burdock, ginseng, nettle, rhododendrons, and various weeds that grow among the acres." "Weaving weeds into a crown is ironclad evidence of King Lear's loss of mind. Listening to Greg recite these lines, I could feel the power contained in the names of these plants, the sense of humiliation that burst out. He told me that A Midsummer Night's Dream was written to celebrate the wedding of one of Shakespeare's patrons, and there were a lot of personal and local jokes. One of Parker's elven friends sang a song about the yellow-flowered nine-wheeled grass: "The gold coat is decorated with moles; / Those are the carnelians given by the fairies, / There is a wisp of fragrance hidden in it." She called the flower "close attendant," and it got its name from Elizabeth I's courtiers who jumped around in extravagant gold embroidered costumes.

Yellow-flowered nine-wheeled grass. Infographic

It is true that in all of Shakespeare's works, his language is multi-layered: there are explicit writings, metaphors, and at the same time catchy, a combination of the three, sound, shape, and meaning. His use of weed metaphors shows that weeds are not as simple as they seem (or at least not at the time) on the surface, but are considered only agricultural scourges, but have deeper cultural and ecological connotations that are encoded in their names like genes.

Editor-in-Charge: Wang Yu

Proofreader: Zhang Liangliang