Yao Yufei

Today, diaries have gradually become a popular publishing phenomenon and an intriguing reading landscape. The diary of the Qing Dynasty and the diary of the Republic of China not only received strong attention from the academic circles because of their rich information, but also loved by ordinary readers. Diaries contain historical details and trivia of life that often fascinate and delight readers. The more people want to see the past, the more carefully they look at the diary. "Microscopic" thus became the usual perspective of examining diaries, the basic method of studying diaries, and thus the tone of a series of articles in this column. In order to pay tribute to "Qing History Exploration" and "National History Exploration", this column is specially named "Diary Exploration", which tries to make people enjoy the fun of reading diaries and fully explore the value of diaries, find interesting materials, refine valuable questions, and also explore effective methods suitable for studying Chinese diaries.

Fu Lei's family letter on May 8 and 9, 1955, mentioned: "In order to facilitate the check of whether there is any loss, the letter can be numbered." As of April 30. Thirteen letters you sent back, and according to this number, they were compiled in accordance with this number, and the next letter was written with a number. If one or two letters have been sent home during this period, subsequent letters should be written no. 15 or 16. In your own small book, you should also register the letters and packages sent and received (month, day and number of letters). Fu Lei reminded his son that the numbering of letters was not an accidental innovation, but rooted in a long tradition. China is a great country of letters, and there is a long tradition in China in numbering letters. The letter numbering technology, which was formed in the Ming Dynasty and flourished in the Qing Dynasty, still had an influence after the Republic of China.

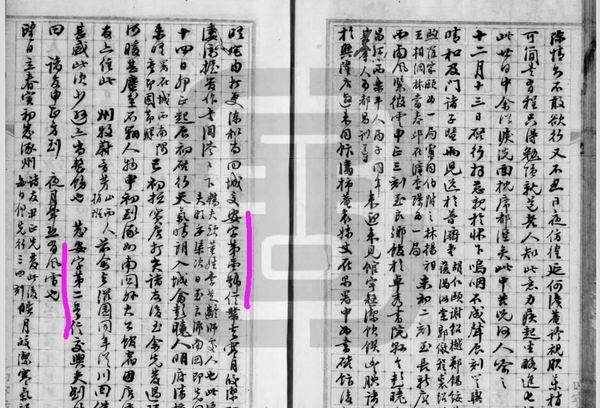

Weng Xincun's "Zhi Zhi Zhi Zhai Diary" Daoguang 13 december 13, 14th year of the letter number

When we trace the origins of this technology, we should focus on the Qing Dynasty. Although Xu Guangqi's family letter reveals that the number of letters was relatively mature during the Ming Dynasty, a large number of records of letter numbers are still mainly preserved in the Qing Dynasty. Reading the diary of the Qing Dynasty, you can often see words such as "Fa Geng Zi No. 3 Letter", "Dejing Zi No. 1 Book", "JieShun Zi No. 4 Book" and so on. Lin Zexu, Li Xingyuan, Weng Xincun, Wang Wenshao, Weng Tonggong, Guo Songtao, Gu Wenbin, Sun Yuwen, Jiang Biao, Wang Chengchuan, Yao Yongkuo, Pan Zhongrui, Liao Shouheng, Meng Sen, Lin Yichang, He Baozhen, Zheng Xiaoxu, Zhang Yuanji, Wang Zhensheng, Lin Jun, Fu Zhang, Deng Huaxi, Weng Zenghan, Liu Shaokuan and others have considerable records of this kind.

These texts related to the letters were intentionally numbered by the Qing people. Thanks to the developed letter culture, the Qing Dynasty gradually developed and matured the use of a series of letter numbering rules to cope with the large-scale correspondence in daily life. Letter numbering has its rules and special connotations, this article uses the diary as a material and means, cares about the external world of the letter, tries to reveal the principle and meaning of the letter numbering technology, and then highlights the characteristics of the diary in the vision of the letter.

I. Application Scenarios of Qing Dynasty Letter Numbering

Letter numbering has a wide range of applications in Qing Dynasty society. The Qing Dynasty continued the trend of good travel in the late Ming Dynasty, and the eunuch literati often traveled widely, while the frequent relocation of officials, the large-scale travel of scholars and literati to make a living, spawned a large number of letters, and the letters produced by this kind of travel at one time and one place were often presented in the form of numbers. The numbering of letters by the Qing people often occurred on travels, or as officials, or to deal with other matters. One side is on the go, the other is at home, and the correspondence between the two sides is often numbered.

Letter numbering is often based on practical needs. The transmission of a large number of private letters often depends on social relations with different degrees of maturity, and the instability of this transmission of letters can be seen from the five letters recorded by Weng Xincun Daoguang from the end of the twelfth year to the beginning of the thirteenth year of Daoguang's trip to Jiangxi Ren Xuezheng.

The transmission of Weng Xincun's family letters to Jiangxi to study politics is shown in the table:

According to Zhang Jian, "Weng Xin Cun Diary" (Zhonghua Bookstore, 2011 edition). Since the diaries of Daoguang from February 13, 1313 to November 9, 14, Daoguang do not exist today, only these five family letters can be counted.

Weng Xincun Daoguang set off on December 13, 12012, and arrived in Nanchang on the 24th day of the first month of the following year. From the above table, it can be seen that Weng Xincun went from Beijing to Nanchang, Jiangxi To study and govern, and issued five family letters, which were transmitted through five different channels. In Liangxiang, a suburb of Beijing, family letters were transmitted by the monk Chen, a datong; in Zhuozhou, they were transmitted by Youfu; to Hejian in Hebei, they were forwarded through Fangshi Wei Maolin (1773-1842 onwards); in Zou County, they were entrusted by Weng Lufeng (Zi Buchu); and in Nanchang, Jiangxi, they were sent by Hu Xiugang. The transmission of the five family letters is completed through five different interpersonal relationships, corresponding to the relationships of initial acquaintance, employment, teacher and student, kinship, and position. It can be seen that for a senior official like Weng Xincun, there is also a lack of a stable channel for the transmission of family letters, so it is necessary to number family letters to ensure the effectiveness of information transmission. In addition, due to the limitations of the conditions for writing letters and sending letters on the road, letters cannot be sent at a stable frequency, and the interval between two letters may often be longer. In the "Book of Pan De Public Opinion", it can be seen that most of the Pan De Public Opinion Books were delivered by Ding Yan, but in the letter, Pan Shi repeatedly mentioned the problem of delayed delivery and loss of letters. At this time, if the letter is numbered and recorded in the diary, it is conducive to the author of the letter recalling the time of the last letter, thus ensuring the continuity of the writing and transmission of the letter.

The form of the epistles also needs to be distinguished or integrated by numbers. Many letters in the Qing Dynasty required "mother-and-son sealing", that is, a letter was often wrapped in other envelopes, and these entrained letters needed to be numbered and distinguished. He Shaoji diary Xianfeng diary on the first day of October of the second year of The diary Cloud, "and to Zhuang Sibai, for Gui to say literary affairs, seal zi yu letter inside." Xianfeng Diary Cloud on the second day of the first month of May in the tenth year of The Diary: "Li Jiesheng twenty-seven allegorical books, there is a son yu a piece of paper." "Carrying other people's letters in the letter is also the best choice to save postage." In the twenty-eighth year of Daoguang, Weng Tongshu went to Guizhou to serve as a scholar, and his father Weng Xincun sent three letters to the family of "Guizi Yuan", which were written on September 10, September 24, and September 26, respectively, and this noble letter was sent out together with the letter sent to others. In addition, letters of different sizes can also be sent together, such as on the thirteenth day of the first month of the 29th year of Daoguang, Weng Xincun sent "Guizi No. 2 and No. 32 Trust Zi Lian Forwarding" to Weng Tongshu. Among them, the second book of Guizi was written on the 25th day of December in the 28th year of Daoguang, and when it was ready to be sent by the Tiancheng Letter Bureau on the 27th, the ship was suspended, so it was delayed until the following year, and it was sent together with the third letter of Guizi made on the 12th day of the first month of the 29th year of Daoguang.

The numbering of letters is intentional, but sometimes it does not begin to be numbered in one place. At the end of the Qing Dynasty, Feng Quan, the deputy minister in Tibet, only numbered the family letter after he arrived in Tibet, and before that, he could do it at any time. I am afraid that it is related to the inconvenience of transportation after entering Tibet and the fear of the loss of letters.

The letter number is generally written on the envelope so that the recipient can see at a glance, and it is also written in the body of the letter. For example, the "Letter No. 17 of An Zi" written to him by Wen Pei Guangxu, the wife of Feng Quan, the deputy minister in Tibet at the end of the Qing Dynasty (1905), was paid as "No. 17 of the Second More An Zi on the fourth day of the first month of March."

The numbering of Qing letters often occurred between close family members, and the correspondence between friends and friends outside the family and even non-core members of the family was often not numbered. In the diaries of Lin Zexu (1785-1850), Zeng Guofan (1811-1872) and others, there is a wealth of information on the correspondence between books and books, but only letters between family members are numbered. This is both a reflection of the ancient family culture and the relationship between the five luns, and also reflects that the exchange of letters by number may require the accumulation of certain letters. Those who can maintain correspondence for a long time during the journey are usually family members, and long-term correspondence has a large number of letters, so they must be numbered. Once the whole business trip was over, the letter numbering was also declared over. For example, the Suzhou man Pan Zhongrui (1823-1890) recorded that he accompanied his brother Pan Xia (1816-1894) to Hubei as a deputy to the envoy Si Yamen, and sent the first letter to his brother Pan Maoxian (Zi Songsheng) from April 24, and the diary recorded that Yun, "as the first book of the Song Brother Ezi", this letter number lasted until August 16, "to make the seventeenth book to Song Brother Ezi", and a few days later, Pan Zhongrui returned to Suzhou by boat. On August 19, he arrived in Shanghai, and at this time the diary only recorded "make a book to send Su", which is no longer numbered. During the whole hubei trip, Pan Zhongrui also numbered the letters from his hometown in Suzhou, such as the diary recorded on August 19, "Receiving Brother Song's Su Zi No. 12 Letter" and August 18 receiving "Brother Song's Fourteenth Letter". During the four-month trip to Hubei, Pan Zhongrui wrote 17 letters to his home and received a letter No. 14 from home.

Using the diary material, the basic situation of the letter number can be revealed more completely, and then the value and significance of the letter number can be analyzed. From March to May of the seventh year of Guangxu (1881), Pan Zhongrui returned to Shexian County to exhibit tombs to deal with the burial of the coffins of the ancestors of the Pan clan in Dafu County, Shexian County for a hundred years, and the funds sponsoring this matter came from the Suzhou Pan family, and the specific measures occurred in Shexian County, hundreds of miles away, so information communication was very important. During the two-month trip, Pan Zhongrui's correspondence was recorded in his diary, where the diary became the index and thread of the letters, and the letters became the hidden clues that connected this period of time. The correspondence of Pan Zhongrui's "Diary of Shexing" is made into a table, which shows the frequency and numbering nature of the letters.

A list of correspondence contained in Pan Zhongrui's Diary of a Journey:

According to Yao Yufei' collation of "Pan Zhongrui's Diary" (Phoenix Publishing House, 2019), combing.

From the first letter sent on the eighth day of March to the last letter on the second day of May, in fifty-four days, Pan Zhongrui sent eleven letters to Suzhou, an average of one letter every five days, except for the end of April when he went to Huangshan, about five days to send a letter. Letters received from Suzhou from March 21 to the first day of May, 8 letters were received in 40 days, which is roughly one letter every five days. The average postal time of letters sent from Suzhou to Shexian is about 10 days, and considering this time difference, if Pan Zhongrui travels for a long time, the frequency of communication may become more and more stable. The emergence of this relatively stable situation of receiving and sending letters benefited from the convenience of transportation in the Qing Dynasty, and the waterway itinerary in various places was very perfect, which was conducive to the circulation of personnel and information. In addition, the convenience of the transmission of letters in the Qing Dynasty also benefited from the developed postal system. In the Qing Dynasty, postal stations were composed of post, station, pond, station, institute, shop, etc., realizing the merger of "post" and "post", and collecting the culmination of the postal system of the previous dynasties, although it was originally for official service, in fact, many officials and writers passed on private letters.

It can also be seen in the table that the letters from Pan Zhongrui and relatives and friends in Suzhou are only numbered by Uncle Xipu (Pan Zunqi, 1808-1892), and others such as Pan Maoxian (Brother Song Sheng) are not numbered. Whether the letters are numbered or not, what is the reason for their dominance? If it is recognized that the purpose of Pan Zhongrui's visit is to deal with family affairs, it is not difficult to understand this numbering behavior. Pan Zunqi is the honorable head of the Pan clan in Suzhou, or the Pan family Songlin Yizhuang Zhuangzheng, handling the matter of the tomb of Dafu Zhan and the burial of the coffins of the clan, Pan Zhongrui is the actual executor, and the commander-in-chief behind it is Pan Zunqi. From this point of view, among the numbers of many family letters, letters dealing with important affairs are numbered in priority, while other general family letters are not numbered. Letter numbering shows that this set of correspondence relationships occupies a very important place in many letters between the numberers.

There is also a mismatch in the numbering of letters, i.e. one party is numbered and the other party is not numbered. In the tenth year of Guangxu (1884), Pan Zhongrui's brother Pan Wei served as a political envoy in Jiangxi, and Pan Zhongrui wrote a letter to Pan Xia in his hometown in Suzhou, all of which were numbered, and by the time Pan Zhongrui was impeached and stepped down, it had been numbered to the twentieth. However, Pan's letters to Pan Zhongrui were never numbered, and Pan Zhongrui did not number themselves. This seems to indicate that letters do not necessarily need to be numbered for those who are at home and in a fixed place of residence. In addition, it may also indicate that Pan Zhongrui attaches great importance to the relationship with Pan Xia, but Pan Xia does not value Pan Zhongrui so much. The asymmetry of letter numbering is a visual manifestation of the asymmetry of interpersonal relations between the two parties.

2. The manner and value of the numbering of letters

Judging from the numbering of Qingren's letters contained in the diary, the Qing people often used two numbering modes for letters: one was the double numbering of words and numbers, and the other was a simple numbering. In both epistle numbers, the numbers are basically sequential, starting with "first" and ending with numbering, sometimes starting with "one". This numbering method is more straightforward, but when there is multi-party communication, or when the author is distinguishing, it is often double numbered with words and numbers.

In the double numbering of words and numbers, the main difference is the choice of words. There are three kinds of text differences in this numbering method: one is named after the abbreviation of the location of the other party receiving and sending the letter, and the text is mostly shorthand for the address. For example, the words "鄂", "苏" and so on used in Pan Zhongrui's numbering above. In the twenty-eighth year of Daoguang, Weng Tongshu was appointed as a scholar in Guizhou, and the letters exchanged with his father Weng Xincun used the word "Gui" when numbered. The second numbered text can also be derived from the thousand-character text, and the text can also be the year number, or the heavenly stem and earth branch in the dry branch year. For example, in the nineteenth year of Lin Zexu Daoguang's nineteenth year as a minister of Chincha, he went south to Guangdong to preside over the anti-smoking matters, and the number of the letter was "self". On the third day of the first month of the new year, Lin Zexu arrived in Nanchang, Jiangxi, and his diary read, "Fengzi Zi No. 3 Family Letter." The word "己" should be taken from "己海", that is, starting with the Tiangan character number of the Ganzhi Chronicle. However, the numbering of individual letters can also vary from place to time. In the twenty-second year of Daoguang (1842), Lin Zexu moved to Yili, Xinjiang, and wrote a letter numbered only in numbers. Another example is the Republic of China (1913), the bibliophile Wang Baochen (1890-1937) "Xishan Small Farmer's Diary" in the letter named after Tiangan, and the receipt of the letter is based on the number of the earth branch. Some of the days of September of that year are recorded as follows:

(September) 4th Day Get up early. In the afternoon, I recorded my own poem, clicked on the five pages of "Tang", titled "Peony Pavilion" two absolute, and received a letter from Hui Nongzi. Under the lamp, read the "Legend of Swallow Notes".

On the fifth day of the first year, get up early. In the afternoon, as usual, I sent Huinong's letter B and ordered ten pages of "Tang Poems".

Thirteen days Get up early. In the afternoon, as usual, I ordered fifteen pages of poetry, and sent Huinong's letter and poems. Under the lights, click eighteen pages.

Eighteen days Get up early. In the afternoon, order the "Annals of Fishing and Oceans", send a letter from Hui Nongding and write several recent poems.

Twenty-three days Early rise. In the afternoon, as usual, I ordered six pages of poetry. Go to Uncle Yu and receive the letter from Hui Nongyin. Under the lamp, the nine pages of the poem are lit.

Twenty-four days Early rise. In the afternoon, as usual, I ordered five pages of poetry. Send a letter from Huinong E to Uncle Blunt.

The number of the Tiangandi branch is at the end of the year, and it is very convenient to record the diary. For example, the "Diary of the Northbound Journey" of Huang Peifang (1778-1859), a native of Xiangshan, Guangdong, contains the circumstances of jiaqing jidi (1819) and Gengchen (1820) sending and receiving letters, of which the "letter No. 1 of the Beijing 卯 No. 1" was issued from February 28 to the 23rd of December, with the beginning and end intact. The following year (庚辰), Huang Peifang's letter number was numbered with the word "Chen".

Letter numbering contained in Huang Peifang's Diary of a Northbound Journey, edited by Sang Bing, Volume 1 of the Manuscripts of the Qing Dynasty, Guangdong People's Publishing House, 2007, pp. 244-245.

Third, there are some auspicious words that are also widely used for epistle numbering. Such as "peace and smoothness" and other blessing words. For example, in the "Diary of Erle and Bu", on July 25, 1870, the ninth year of Tongzhi (1870), the difference between "letters with Shunzi No. 3 and letters from relatives and friends", it is mentioned here that the number of the family letter is "Shunzi No. 3". Words like "safe and smooth" imply a safe and auspicious journey, and are often used in travel, which is a reaction to the uneasy mentality of the journey. When Erle and Bu Tongzhi lived in Shengjing for nine years, the number of correspondence with their families in Jingshi was a numeric number, that is, the "x" family letter. Of course, this numbering is sometimes mixed, so it can be seen that the numberer of the epistles uses it more casually here. Other letter numbering may be based on the default numbering of both sides, such as Hu Linyi's letter "Concubine of Cheng's Mother-in-Law and Father-in-law Tao Shu" mentioning that he used the word "Grace" for letter numbering. At this time, Tao Shu died, and his family planned to transport his coffin from Jiangning back to Anhua, Hunan. Here, the meaning of the word "grace" is not clear, which may express the meaning of Hu Linyi not forgetting the grace of his father-in-law Tao Shu. Some of the signs of epistles are not numbered, but merely pronouns. For example, from the sixth day of the first month of the tenth year of Guangxu to the ninth day of the first month, Jiang Biao recorded an item of "writing a new year's letter" every day, and the meaning of the text was to write a new year's letter. "Year's letter" means "New Year's letter".

For example, Feng Quan, the assistant minister in Tibet at the end of the Qing Dynasty, wrote letters to his family with the word "Ping", while letters written to Feng Quan at home were numbered with the word "An". At the end of the Qing Dynasty, when Tibetan affairs were complicated and delicate, the number of Feng Quan's letters to and from his family implied a wish for "peace". Some of the letter numbers are unclear, such as Jiang Biao's diary Guangxu Sixteenth Year (1890) began to send "Xizi No. 1 Family Letter", November 24 "SendIng Xi Zi Second Ceremony", Guangxu Seventeenth Year February First Day "Shangxi Character Fourth Ceremony", March 10th "Making Xi Zi Fifth Ceremony", And April 8 "Sending Xi Zi Seventh Ceremony, and Harvesting Autumn Book". Judging from the diary records, this series of letters sent from Beijing to his hometown in Suzhou was written to Jiang Biao's mother. In November of the sixteenth year of Guangxu, Jiang Biao moved to Beijing with his family, or was quite happy, so he named this series of letters after the word "xi". However, the day before the first numbered letter, Jiang Biao also went to mourn his mentor Pan Zuyin, so it is difficult to conclude that Jiang Biao was in a happy mood at this time.

Some of the words used for epistolary numbering may be used repeatedly. Weng Xincun Daoguang served as a scholar in Jiangxi in the winter of the twelfth year, and issued the "An Zi No. 1 Letter" on December 13 of this year, and the "Cao An Zi No. 5 Family Letter" on the 27th day of the first month of the thirteenth year of Daoguang. In November of the following year, Jiangxi Xuezheng was succeeded by Xu Naipu (1787-1866), and in November, Ri Weng Xincun set off from Nanchang, and on the evening of November 26, he sent two children to the "Cao'an Zi No. 1 Home Letter" in Lingbi, Anhui. It can be seen that the word "An" is a word that Weng Xincun uses more often when he is numbered as a family letter.

Moreover, the double numbering of words and numbers in the numbering of epistles is not a meaningless and cumbersome exercise. At least as far as the current situation is concerned, those who use words and numbers for double numbering tend to do frequent business trips, and the number of letters sent and received is very large, and most of them have a sense of literature preservation. In this way, the text in this number has a significant marking effect, which is convenient for users to quickly find letters when reviewing or sorting out letters, and it is also conducive to the archiving of letters. In this regard, the numbering scheme was heavily used in various areas of Qing dynasty life. Since the Tang and Song dynasties, it has been common to number personal belongings, and Qing Dynasty books, calligraphy and paintings, rubbings, book boxes and other items have a variety of numbers. This tradition of numbering objects may affect the numbering of letters. In addition, in addition to private letters, the management of letters by institutions is more standardized. In the operation and management of Shanxi Jinshang Ticket Number, the most important thing is the "letter management". He Zhuang's "Preliminary Study on the Archives of Jinshang Ticket Documents and Their Management" generally reads: "The × month × date from the ×× to the ×× the ×× letter" or "the × month ××× with (forwarding) to the ×× letter". The number contains information such as the time of issuance, the sender, the recipient and the number of letters, which is similar to the number of today's official documents, has the functions of sorting and for reference, and also provides conditions for subsequent management work. "Not only are they numbered, but the letters are also numbered. The numbering of letters by the literati of the Qing Dynasty was an inevitable measure for individuals to face a large number of letters. The handling of rich letters institutionalized many Qing Dynasty literati and had to undertake the function of handling letters similar to that of business names.

The numbering of letters appears as a conscious act of documentation. Although the literati's self-compiled collections of letters have appeared since the beginning of the Southern Song Dynasty, the universality and scale of many self-compiled epistle collections by many literati in the Qing Dynasty were beyond the reach of previous generations. For example, Tan Xian's self-compiled "Futang Teacher and Friend Codex", Yuan Chang also "hand-compiled letters from friends and friends, decorated into a book, and the inscription "Stopping clouds and leaving traces". The fact that letter numbering can facilitate the compilation and inspection of epistolary collections may also be the reason why letter numbering is widely used. It is probably no accident that those who consciously number letters often have a large number of letters in existence. In the diaries of Tan Xian and others, there are also records of his own collation of letters. Hu Shi, who is good at preserving documents, clearly marks the number of words in each letter, so as to pave the way for the future compilation and publication of letters.

A copy of Hu Shi's self-edited catalogue of letters, see Geng Yunzhi's Manuscripts and Secret Letters, vol. 13, Huangshan Book Society, 1994, p. 258.

Numbering letters is not only helpful for archiving and sorting letters, but also convenient for checking whether letters have been lost. Guo Songtao's diary Guangxu 3rd year (1877) on the seventh day of the first month of May, received a letter from his brother Guo Luntao (Zizhicheng) on the fourth day of the first month of March, Xiao Zhuyun: "A letter on the fourth day of the first month of the first month. At this point, it is the second letter, and the letter is also number two. And Yun Zhengyue Twenty-Eight Tiger Xuanshang has brought a letter from Shanghai, why not?" This letter, Guo Luntao, compiled himself as the second number, but in the letter said that his son Guo Huxuan still carried a letter on the twenty-eighth day of the first month. Guo Songtao thus doubted the whereabouts of the letter. It can also be seen from this that the numbering of letters sometimes does not follow the number of the letter writer, but the author renumbers the letters received. This situation is similar to the current courier station recoding the waybill number. For Guo Songtao, who had crossed the ocean, the number of letters was very critical. According to the diary, on the ninth day of the first month of May, Guo Songtao received a package no. 23 from the Bureau of Literature and Periodicals from march 22, including the no. 2 home letter. On May 23, the Newspaper Bureau was sealed on March 29, 24. On the fifth day of the first month of June, the Bureau of Culture and Communications received the twenty-sixth encapsulation on April 14 (delivered by the British Company's Golizhi ship. Its Twenty-Fifth was delivered by the Meijiang Ship and has fallen to the Ocean and the Sea), and guo Luntao's third letter is attached. On the fourth day of the first month of July, he received the sixth letter, "the two letters of the fourth (April 13th) and the fifth (April 25th) have not yet been received." For Guo Songtao, the loss of family letters is still a big problem. Perhaps it was precisely because of the uncertainty of postal transmission between China and Europe at that time that Guo Songtao took the trouble to number letters and packages. The loss of letters suffered by Guo Songtao was not an isolated case in the late Qing Dynasty, and even in China, the loss of letters was a common occurrence. For example, wu Yinpei, a Suzhou tanhua in Beijing, recorded in his diary on the sixth day of the first month of October 1901: "On the day, I got the third family letter, and I knew that the second mail had not arrived." This situation may not have improved much during the Republic of China, so a large number of family letters written by Liang Qichao, Hu Shi and others often used numerical numbers.

In order to ensure the accurate transmission of letters, the qing letter numbers were not only for the envelopes of the letters, but also for the main text of the letters. This double numbering of the text of the letter and the envelope has its significance, such as Lin Zexu Daoguang's December 14, 2022 "To Lady Zheng and Lin Ruzhou No. 16" letter, which states that the eleventh family letter was received within forty-six days, which was very fast, "but the envelope was completely torn apart, and the red paper and copy of the family letter were exposed, which was obvious to all, although it was extremely hateful, but it was nothing like it." There is no scruple in the station, as far as this is concerned. "Letters sent by the station may lose the envelope, so the envelope number is not insured. Another example is Chen Yongguang's "Taiyizhou Anthology" Volume V "Book of Bozhi": "Recall that in June, two letters were sent on the sixth and sixth, and the letter sent in this month was listed in the seventh number, but Lan Rui did not know, but the external number was not listed, which showed his carelessness." This time I am still listed number seven also. "The letter does not have a time to be paid, but it can still be inferred from limited information. In this letter to his nephew Chen Lanxiang (Zi Bozhi), Chen Yongguang criticized his son Chen Lanrui (1789-1823) for being careless. Chen Yongguang numbered the letters to Chen Lanxiang, and in June he wrote two letters, numbered six and six. This month (when it was July), another letter Was written, but when Chen Lanrui sent the seventh letter, there was no number on the envelope, so that Chen Lanxiang was suspicious of it, so Chen Yongguang explained it in the letter. This material indicates that the letter has a number inside and outside, which is a double insurance, but the registration is often based on the envelope number, so Chen Yongguangxin's letter is still numbered as no. 7. It also reveals that the epistle number may be incorrect. Of course, there are also envelope numbers, and the body of the letter does not mention the numbered information. For example, on February 27, 1850, the 30th year of Daoguang (1850), Weng Xincun "obtained the Gengzi Yuan number book issued on the 25th day of the third month of the first month, and ten pieces outside", but this letter was not numbered in the main text of Weng Xincun's letter.

For Qing letters, the number may be more true than the date on which the letter was written. Weng Xincun's diary Daoguang 20 years on the first day of February recorded, "Fa Geng Zi No. 1 Family Letter. (Signed on the 29th day of the first month)", in fact, this letter was written on the thirtieth day of the first month. The diary of the second day of the first month of February, "also wrote a letter to Yangzhou Shoudaiqing in the same year." (Signed on the nineteenth day of the first month)". This indicates that the participation in the numbering of letters, if the number exists in the content of the letter, the specific date is filled in the envelope. If the letter is unnumbered, the specific date information is reflected in the text of the letter. The actual time of the Qing people's letter writing, the time of payment, the time of sending the letter, the time of sending the difference, and other places are not consistent most of the time, and it is not reliable to judge the order of some letters only from a certain date information. There are also some letters that do not have dates. Weng Xincun kept a diary Daoguang on July 3, 299, "Bo Twilight got Wang Xiaoshan's book, (not the book of the month and day, but the clouds and the sun are sunny, the water has not receded, about June 10 or so book also.) At this time, if the number of letters is followed, the relationship between the time of writing can be clarified.

3. The number of the family letter of Weng Xin's twenty-ninth year of Daoguang

In the twenty-ninth year of Daoguang, Weng Xincun went out of the mountains again, and set out from Changshu to jingshi in the spring. Since then, he has maintained close correspondence with his hometown in Changshu and his son Weng Tongshu, who is a scholar in Guizhou. For the letters on these two stable communication lines, Weng Xincun was numbered. This provides vivid case studies of the role of epistolary numbering in the daily life of individuals.

The twenty-ninth year of Daoguang was a relatively frequent year of correspondence with Weng Xincun. According to the receipt and dispatch of letters contained in the "Diary of Weng Xin Cun", the preliminary statistics of the number of monthly correspondence are: 27 letters in January, 10 letters in February, 8 letters in March, 15 letters in April, 18 letters in leap April, 30 letters in May, 25 letters in June, 14 letters in July, 30 letters in August, 24 letters in September, 11 letters in October, 32 letters in November, 38 letters in December, and a total of 283 letters were received and sent this year. Among them, 76 letters were exchanged with close relatives, accounting for 24.7%. Most of them are numbered, which shows the weight of family in Weng's mind. At the end of the diary of that day, Weng Xincun wrote: "At night, I feel nostalgic for the moon, and I can't help but feel sorry for my children and grandchildren who are far away from my knees, or hundreds of miles away, or thousands of miles away." The family letter became a spiritual comfort for Weng Xincun in the face of his relatives' situation at the end of the world, so he carefully managed it here.

In this year, Weng Xin had dealt with 76 family letters, and if it was not managed by numbering and other means, the entire communication connection could be chaotic. Even though Weng Xincun managed family communication between the two most important regions in the sequences of "gui" and "己字", there were still some problems with the number of letters. Fortunately, these small problems are mostly caused by the wrong number. With the arrival of the Gengji New Year, the number of the letter sent by Weng Xincun to his family was immediately changed, and on the thirteenth day of the first month of the 30th year of Daoguang, "The First Book of Fa Gengzi". The number of letters in the home also changed, such as on February 3, "The First Book of the Fifth Son's First Moon Looking at the Day". However, for the letters of Weng Tongshu in Guizhou, Weng Xincun still used guizi numbers, and the order was inherited, such as the eighteenth book of Guizi on the twentieth day of the first month of the 30th year of Daoguang. However, weng Tongshu's letters from Guizhou were already numbered by Tiangan, and on February 27, 30th of Daoguang, Weng Xincun "got the Gengzi Yuan number book issued on the 25th day of the third month of the first month." This shows that for Weng Xincun, the connection with his hometown in Changshu is quite stable, so with the arrival of the New Year, the number changes accordingly. However, Weng Tongshu, who was far away in Guizhou, made Weng very worried, and he chose to continue to arrange this series of letters in the word "Gui". This numbering method began on the twenty-eighth day of September in the twenty-eighth year of Daoguang (1848) and ended on the eighth day of the first lunar month of the third year of Xianfeng (1853) and was numbered to the sixty-second. Spanning five years and 62 letters, the traces are all seen in Weng Xin's diary, which proves the deep love between father and son. In the first month of the third year of Xianfeng, Weng Tongshu's two terms of office in Guizhou xuezheng expired, and he planned to return to Beijing to report for duty. Upon hearing this news, Weng Xincun initially changed the number of the letters with Weng Tongshu to the word "Ping". On the tenth day of the first month of the third year of Xianfeng, Weng Xincun's letter to Weng Tongshu was marked in his diary as "Pingzi No. 1". Weng Xincun changed the number of the letter from "Gui" to "Ping", and from then on, the suspense of Guizhou became an expectation for his son's return to Beijing, "the word peace is worth thousands of gold", and a father's wish jumped on the paper.

The numbering of letters became a striking textual landscape in the diary, drawing attention to what was the most important relationship of the diarist in a certain time and space. People communicate with others, and family members are undoubtedly the most closely related to each other. Daoguang's 29-year-old Weng Xincun sent and received 283 letters, and 76 correspondence with his family, far exceeding other types of interpersonal relationships. In fact, there are many letters that are transmitted through the channel of family communication, symbolizing the attachment of other interpersonal relationships to family relations. As Weng Xin recorded on November 17, 2009, "The eleventh book of the Fa Zi Zi contains a letter to Ni Observation, the Second Nephew, and Shao Xiang, and a letter from Zeng Yuan to his brother." "The important position occupied by family letters in the personal communication network once again shows that the family is indeed an extremely important factor in the cultural ecology of the Qing Dynasty." The number of the family letter is a declaration of this solid and continuous relationship. Not all epistle numbers occur between relatives, and other relatively stable relationships with close friends also contribute to the numbering of letters. For example, Tan Xian Tongzhi had a close correspondence between the three years and four years and Zhou Xingzhi, and the twenty-seventh day of December of the third year of Tongzhi recorded that the "Seventy-fifth Book of Supplements and Seasons" shows that tan xian's letters to Zhou Xingzhi this year have reached 75. Continuous correspondence numbering is the embodiment of strong interpersonal ties, and those that are not numbered may also contain very important content, but the two parties to the communication are not intimate and stable relationships, but appear as weak connections.

Not all family letters are numbered. It can be seen from the above table that the letters between Weng Xincun and his grandson Weng Zengwen are not numbered, nor are the letters exchanged by Weng Tonggong during his travels. This situation may be because the correspondence between Weng Xincun and Weng Zengwen is only an occasional branch between the communication between the large family and the individual, which is an accidental sexual act and lacks continuity. As for the correspondence between Weng Tonggong and Weng xinxin this year, they are also in a state of instability. In the spring of that year, Weng Tonggong went north with his father and did not have to communicate. On May 11, Weng Tonggong returned to his hometown to take the test, and when he arrived home on June 6, weng Tonggong wrote letters halfway through, according to Weng Xincun's diary, there were four letters: on May 14, Hejian Twenty Mile Shop, On May 20, On May 20, Yuan PuZhouci, and on the first day of June, Yangzhou issued, but in Weng Tonggong's diary, only the first two writers' books were recorded. It can be seen that Weng Tonggong during the journey did not particularly care about this. After all, the trip was just over a month old. After returning home, Weng Tonggong's communication channel with his father was again added to the communication connection of the entire large family in Changshu, so there was no need to number.

Even though the close correspondence between Weng Xincun and the sons of Weng Tongshu of Guizhou and Weng Tongjue of Changshu was mostly numbered, some of the letters were still consciously "out of numbers". Taking the diary of Weng Xincun in the twenty-ninth year of Daoguang as an example, it can be seen that the following numbers of correspondence are not listed.

On the night of the eighth day of May, he made a book with the five children and handed over the six children to take with him.

May 12 is the first day of the fortyth year of the wife of the third son, who is a soup cake for the family. The grass is not listed one letter and three children, and there is a clothing bag and a boot bag.

On August 1, the fifth letter sent by the third son on the twenty-first day of June did not list two letters, and zhuge stele a piece of paper.

October 4 Issued a noble word not to list the family letter and a bag of clothes and a boot bag, and Tuo Nguyen Hou Ting took it with him.

October 5 Issued a family letter with a noble character and two letters from Shao Xiang. The outer brown bag, mushroom, and green peach were handed over to He Lishan to take with them.

In the correspondence between the two sides with continuous numbers, there may be two reasons behind the sudden intention to insert some unlisted letters: one is that these letters may involve some secrets, about human feelings, requests for trust, etc., so such letters often come with some items; second, the unlisted books have a reliable sender who can ensure the safe delivery of the letters, so there is no need to be numbered.

Although the Qing dynasty's postal system was relatively well-developed, the risk of instability remained. Weng Xin kept Daoguang's diary of April 20, 20013, "The fourth book of the fourth day of the fourth day of the fourth month of the fifth son, the first two were destroyed, and the situation was robbed on the way." "Daoguang 30 april 23rd," received the third book of the fifth day of the fifth month of March, from Tiancheng, fifty days naida, can be described as late. "The risks of transmission of letters make it imperative to number them in order to preserve the validity of the transmission of information.

In addition, although Weng had a deliberate intention to number the letters, he was too busy with daily affairs, so the number was frequently signed. On November 15, 2009, Daoguang "obtained the eleventh book of the twenty-sixth day of the twenty-sixth day of the fifth and sixth months (Shi No. 12, mistakenly signed)". Weng Xincun's diary was often recorded according to the facts, but after seeing other letters, He understood that he might have misunderstood the serial number in the early days, so he often explained it in the original text of the diary. This also reflects the large workload of the Qing people in handling letters on a daily basis. For Weng Xincun, the diary holds the consecutive numbers of letters, which is equivalent to a register for sending and receiving letters. Here, the diary provides an intuitive memorandum for the sending and receiving of letters, and the receipt and reception of letters can therefore be entered into the diary in a dignified manner, becoming a must-have item in the diary. As a result, the diary, which undertook the function of memo, eventually became an important form of writing for the Qing dynasty, and an indispensable form of writing for daily life. In this process, the epistles play a role in the symbiosis of hooking. Letters entered the diary, and the diary inevitably recorded the letters, and as the Qing people's letter writing and diary writing became more common, the letters and diaries increased each other's dependence on each other.

Fourth, continuity: public and private, scholarly society and humanity

As we turn our attention to the broader social stage, to the stage of public scholarship, thought, and public opinion, whether letter numbering is still working effectively and what is the difference in its role. In the Qing Dynasty, there was not only a scholar society, but also a letter society. In the Qing Dynasty, the outline of the "literati republic" began to take shape, and the letters played a great role. As Ehrman said in his book From Science to Simplicity, there were many scholars in the Qing Dynasty like Qian Daxin, "with the help of this method (letters) can be pertinently evaluated, recognized and widely noticed by the academic community." "Letters of this kind of academic exchange are often of a public nature, and the numbering method is also different from that of private letters.

The numbering of public correspondence tends to be highly marked. On relevant academic issues, ideological propositions, literary issues, etc., this kind of treatise, thesis and other books, eventually presented in the Qing Dynasty collection, are often marked as "with (answer) so-and-so on so-and-so books" and other forms, such as Zhang Xuecheng's discussion of Fang Zhixue's books, that is, "Answer Zhen Xiucai on Xiuzhi First Book", "Answer Zhen Xiucai on Xiuzhi Second Book" and so on. The numbering of such letters is mainly generated around the content, so its numbering information mainly focuses on the characters and contents, and then names them in numerical order. Compared with the above-mentioned private letters, it is not difficult to find that the numbering of such letters often ignores time and place information, and emphasizes more on the object of the letter writing and the content of the focus, especially the content, often throwing out a few keywords to summarize the main issues discussed. Therefore, unlike private letters, which are numbered for daily affairs, the numbering of such letters is generated by the discussion of academic, ideological, and other issues, and the development of their numbering also increases with the deepening of the problem, and the numbering ends when the discussion of the problem is over. Since the numbering of the epistles is based on the content, it is not necessarily a true reflection of the order of correspondence. Although the numbering of the epistles is clear, and the issues concerned with the epistles are continuous, most of the epistle numbers are the product of the compilation of epistles, not the actual situation of correspondence transmission.

In many ways, there was a world of book weaving in Qing Dynasty society, and there was also a world of letter weaving. In terms of the weaving of letters in the academic world, Liang Qichao has pointed out in his Introduction to Qing Dynasty Scholarship that Qing Scholars "have every righteousness, and they are friends of their common learning ... Whoever writes a book will be carefully surveyed by his best friends for generations, but it will be published, and its investigation will be written by letter. ...... This kind of atmosphere also existed in his time, and The Qing Dynasty was unique. Taking Li Rui, a famous arithmetic scholar in the Qianjia period, as an example, In the eleventh year of Jiaqing (1806), Li Rui lived in Suzhou and never went out, but according to the statistics of his "Guan Miaoju Diary", Li Rui's correspondence this year was still as high as 92, most of which were on books with Ruan Yuan, Jiao Xun and others. In the spring of the fifteenth year of Jiaqing (1810), Li Rui was in the Nanchang Prefecture Office in Jiangxi Province, and it is said that the diary statistics, the number of letters written reached 30, except for the 4 family letters of "Gengzi", the remaining 24 letters were mainly with friends and friends, of which the letters with Yun Jing and others were obviously mainly papers and treatises. In terms of the weaving of letters in the family world, the individual and the other party in the five lun relations almost all have correspondence. That is, from the perspective of gender, the wide circulation of female letters since the 17th century constitutes the "epistle world of talented women" (for related discussions, see Wei Ailian's "Writing, Reading and Travel of Talented Women in the Late Ming Dynasty"), and various female rulers are not uncommon.

The phenomenon of the Qing people weaving the world with letters had a real impact, that is, the cluster effect was often created through continuous letter numbering. Highlighting the continuity of a transaction helps to increase the value of the transaction, making it a more compelling "landscape". In the case of private correspondence, the continuous numbering highlights the importance of this period to the life of the epistle author, as a thematic exhibition of family life or friendship portrayals, or a kind of periodic summary. For public correspondence, continuous numbering implies a thematic discussion of relevant issues. Such topics can be theoretical propositions, political opinions, a certain type of ideological problem, or the expression of contemporary opinions. Through numbering, public discussions are limited to specific intervals, outside of numbering, and such discussions cannot have a holistic impact. In short, the numbering brings together these epistles, giving them relative independence and thus acquiring the meaning of completeness. Sometimes, these numbered letters also have an "intertextual" effect. Carefully labeled letters are deliberate divisions of everyday life and an effective division of public topics. The numbering of correspondence with family members indicates that this series of letters has a unique significance in family life, while the numbering of public treatises indicates that this series of letters discusses important issues with me and is worthy of repeated discussion. The numbering of letters named after the destination may be considered a commemoration of a journey. Through numbering, letters became an effective means for the Qing people to mark their daily lives, and became a physical means of distinguishing academic and ideological problems in the Qing Dynasty. Through the clustering effect of letters caused by numbering, letters are better involved in public affairs, and also provide an intrinsic and solid emotional bond for personal relations and social interactions.

Various interpretations of the number of letters are helpful for understanding the literati society of the Qing Dynasty and the personality of a specific literati. First, the letter number may reflect a person's character. He Shaoji's diary contains more than 600,000 words, and many of the letters are recorded, but they rarely use numbers as numbers, and occasionally or numbered, they are also intermittent. He Shaoji more often used the date plus name or the location plus name to name the letter. It seems that he recorded the receipt and dispatch of letters in his diary, mostly as a memorandum, and did not intentionally value the continuity and systematization of the letters. After He Shaoji's death, a large number of calligraphy, paintings and manuscripts in his collection have not been preserved in their entirety or are related to this. Unlike He Shaoji, Changshu Weng Tonggong, Suzhou Pan Zuyin and others seem to have a fondness for letter numbering, and their related literature can be preserved in large quantities after their deaths or are also related to the way they handled the documents before their deaths.

In addition, the continuous numbering of letters reinforces the regional perspective of the daily interactions of the Qing people. The temporal and spatial information presented in the letter numbers is constantly changing and shifting as the letter numbers travel, drawing attention to the flow of information between the entire imperial territory. Based on intuitive impressions, it can be preliminarily inferred that in the numbering of relevant letters in the Qing Dynasty, the words "Jing" and Jiangnan and other places undoubtedly appear the most, which shows that Beijing and Jiangnan were the centers of communication between the literati and scholars of the Qing Dynasty, and once again shows that these two areas are the highlands of Qing Dynasty culture. Correspondence between Kyoshi, Gangnam, and other places is intuitively presented in the frequency of the regional abbreviations of the letter numbers. For example, the geographical abbreviation of the number of letters in the Qing Dynasty diary is used for big data statistics, and the geographical distribution map of the exchange of letters of the Qing people can be outlined in a large range. In addition, after Jiaqing and Daoguang, as the literacy rate increased, some female letters also used numbers. This situation is recorded in men's diaries, showing that the relationship between husband and wife changed during this period, or can be seen as a return to the culture of women in the late Ming Dynasty. The continuous numbering of letters made this batch of letters increasingly important, and eventually became a representation of the remarkable times.

5. Diary: Record the life history of epistles

The diary section reproduces the scene of the active letter and preserves the information of the external world of the letter to the greatest extent. In contrast to pure collections of letters, or texts of epistles in collections, diaries provide a trajectory of the flow of letters in everyday life, outlining how letters work together to create the daily life and social connections of the literati. Because of the existence of diaries, information about the beating of letters in daily life can be roughly outlined. The circumstances in which letters were written are often directly revealed in diaries and may not need to be speculated through the content of the letters and other materials. In other words, the diary provides a direct commentary on the flow of letters. The writing time of the letter can be accurate to a certain hour, the place of writing is a specific space, and the state of mind of writing the letter also has a direct expression. This information about time, place, and state of mind does not come from the content of the epistle itself, but from the account of the external life of the epistle writer (i.e., the diary). Not only can the time and space of writing letters be clearly recognized, but the frequency of writing letters can also be accurately speculated. A considerable number of literati recorded all traces of letters in their diaries, so they speculated on the frequency of sending and receiving letters, so as to make an intuitive judgment on the position of letters in the lives of literati.

Not only are the scenes of letter writing kept in the diary, but the complexities of the transmission of letters are also clearly reflected in the diary. The means by which a letter was transmitted, such as the postal system, private representation, etc., are revealed in the diary. What is more interesting is that for some important letters or letters that are at risk of reception, diaries often mark out the people who deliver the letters, they are either compromises in a certain place, or relatives and friends in their hometown, or business buddies, or servants in the family, these famous and nameless messengers appear, so that the transmission of letters becomes a warm information relay, an emotional transmission of human stories. The smoothness of the transmission of letters has also become a matter of concern. When natural factors such as disasters or unnatural factors such as war cause problems in the transmission of letters, the concern for the transmission of letters is more than the words of the diary. The transmission of a letter is no longer a calculation of the distance and time difference between the writer and the recipient, no longer an optional footnote to the main content of the letter, it should be perceived and valued. If we carefully read the diary, it is not difficult to find the life history of the epistles.

If the epistle is regarded as a living thing, the diary records the life history of the epistle to the greatest extent possible. The letter is born in the world of the letter writer (who is also the diarist), and through the hands of one or more people, it eventually reaches the end of its life, the recipient. In this process, whether the letter can successfully "grow" depends on the process of transmission. Letter transmission is the long journey of the growth of the physical life of the letter, during which it is either as plain as water, as rugged and dense, or interesting, or boring, but in any case, this journey is the key to whether the letter can eventually "grow". Arriving at the recipient does not mean the end of the life of the epistle, it can be transmitted, transmitted, and thus obtained the meaning of the next stage, but the opening of the second, third, or even multiple "life journeys" of the epistle life is roughly similar to the first journey, so it is no longer specifically discussed.

In order to ensure or determine the completion of this journey, the letter writer and the recipient had to take some necessary means of safeguarding. This means of safeguarding existed in the text of the letters, which directly affected the genre and style of the Qing Dynasty letters. Although letter numbering had appeared before the Qing Dynasty, the qing dynasty's letter numbering technology was more complex and mature than before. The numbering of many of the letters in the previous generation may have been done by the collators, while the Qing people had a more general consciousness of self-compiled letters. Previous generations of letter numbering mostly focused on integrating ideas and content, while the Qing Dynasty letter numbering seems to emphasize more on the reliability of transmitting information. In other words, Qing dynasty letter numbering paid more attention to completeness and was not limited to the daily trivial nature of letters. Part of the reason for this is to ensure the security of the transmission of letters. At the beginning of many letters, it is often necessary to begin with a few sentences explaining the receipt and dispatch of the previous letter or letters, for which the contents of the previous letters must be briefly repeated. For example, Pan Zuyin wrote a letter to Wu Dayi at the beginning of the letter: "Your Excellency, Qing Qing Rendi: Three letters in a row, and I was worried about purchasing the prince's gongding dunshi, thinking that I had reached it first, or I did not reach it." Hereby learn to make it convenient, and then to serve the pleading. (Quoted from Li Jun's compilation of "Pan Wenqin Gongzhi Wu Shuzhai Codex", "Historical Documents", No. 23) The repeated statements in the content of the letters are intended to ensure the continuity of the information conveyed by the letters. In addition to the letters, the diary records both these means of protection and is also a means of guarantee of letters. Letters written into the diary become a memo for the writer to detect the manufacture, transmission, and arrival of the letters. The diary records the receipt and dispatch of letters, the specific channels of transmission of letters and the person responsible, all in order to ensure the effective circulation of letters. In this process, the numbering of letters becomes a letter protection technology used by both the recipient and the sender. Letter numbering ensures the continuity of correspondence transmission, and at the same time can determine the sending and receiving of letters, so that the flow of information between the letter writer and the recipient is not interrupted or misunderstanding. The existence of the letter number also plays a supervisory role for the messenger of the letter, and the person entrusted with the delivery of the letter seems to be under an invisible supervision. Thanks to the existence of the letter number, the circulation of letters can be smoother. Because of this technology, diaries (i.e., epistolary writers) are also able to reduce the amount of heavy epistolary records. Precisely because of the number of letters, the diary writer does not have to record every numbered letter, because the intermittent recording of the receipt and dispatch of such letters does not affect his judgment of the receipt and dispatch of the letters as a whole.

Using the spatio-temporal information provided by the number of letters contained in the diary, it is possible to accurately tie the year and place of the book, thereby improving the depth of the letter collation. In this regard, the collated editions such as the "Weng Tongshu Codex Annual Examination" and the "Yu Fan HanZha Series" have made active explorations. Conversely, an understanding of the numbering sequence of letters also helps to read some ambiguous words in the manuscript diary and to correct some missing words. For example, Weng Xincun Daoguang's 29th year diary records correspondence with his grandson Weng Zengyuan: on April 27, "Fa Mi Zi No. 1 Family Letter", April 26, "Deyuan Sun March 19 Issued Shu Zi No. 4 Book". Judging from the handwriting in the photocopy, it is not easy to determine whether it is "self" or "巳", but the year is the year of self-unitary, and according to Weng Xincun's rules for the numbering of letters, it seems more appropriate to pronounce this word as "self".

Another example is weng Xin's diary of the twenty-seventh day of September in the thirtieth year of Daoguang, "On the twenty-second day, he received the third book issued by the third son of the third child. ...... And the third book issued by the fifth son of the third month", if according to the numbering rules of the letters, it can be known that the word "厶" in the first two sentences refers to eight and ten respectively.

Although relatively simple, epistolary numbering may be regarded as a safeguard technology that has developed and matured around the circulation of epistles in addition to the text of epistles. The use of such assurance techniques has its limits and general rules of application, which can be summarized as follows: in a given period of time, the two parties to the communication are relatively far apart, in order to ensure a continuous and stable exchange of information, one or both parties adopt the method of marking letters. For both parties to the communication, the use of letter numbering technology can not only determine the transmission of letters, ensure the continuity of information communication, but also a private file management technology, which can maximize the classification of private letters, and many large-scale collections of letters are the products under the influence of letter numbering technology.

A series of practices and specific means of operation on the technique of letter numbering are largely preserved in diaries and not within the text of the letters. This reminds us that, in the case of letters, external information of letters may be overlooked. The physical characteristics of the letter, the flow process and the external world in which the letter is active need to be comprehensively sketched by the materials of various parties. The diary preserves various scenes of the birth and growth of letters, including the content of the letters themselves, and thus becomes a valuable material for the study of letters and their external worlds. A diary can not only paint a clearer picture of the world of epistles, but also reveal technical factors that were previously unnoticed, or one of them. This microscopic technique is not meaningless for epistolary studies. It reveals the effective responses of the literati in an era of epistle prosperity, demonstrating their wisdom. If you read the letters and diaries in pairs, it is not difficult to find that for the letter writer, the numbered letter or more important letter, so as to make a judgment on the importance of the letter. In addition, the use of this technique played a relatively important role in the establishment and circulation of complete epistolary archives and in the compilation of epistolary collections in later generations.

The diary here is not only an auxiliary document for the study of epistles, but also an indispensable document for the study of epistles. Diaries are not only material for studying epistles, but also means of studying epistles. Through the numbering of letters, the study of letters was "transferred" to the field of diaries, and at the same time, the study of diaries was "extended" to the category of letters. In this way, it can not only enrich the cognition of letters, but also add new understandings to the function of the diary. The "transition" and "extension" of research on different literature may help to highlight some marginal techniques that are less concerned about traditional category literature research. The richness of information contained in the diary and the almost all-encompassing capacity of the literature determine that it is the most valuable reference system for revealing the many qualities of the category literature. Perhaps when people use diaries, they should not just "stare" at the part they need, but should look back and see what this "gaze" makes them miss. Using a certain category of literature and diaries to refer to each other, so as to deeply depict the contours of the categorical literature and choose the deep-seated characteristics, is a feasible and worthy of looking forward to the research path of the category literature. For diaries, if almost all disciplines can gain a little from it, then the openness of the diary itself is worthy of awe to researchers, and this openness of the diary may contain something quite valuable, and people should not devote themselves to finding something from the diary and filtering out the "gaze" of others. There are many unique things about the diary, and if we give it enough subjectivity, if we have enough respect for the diary tradition, we may be able to go out of the research path that really belongs to the diary.

Editor-in-Charge: Shanshan Peng

Proofreader: Liu Wei