Guide

Did all three pandemics originate in China?

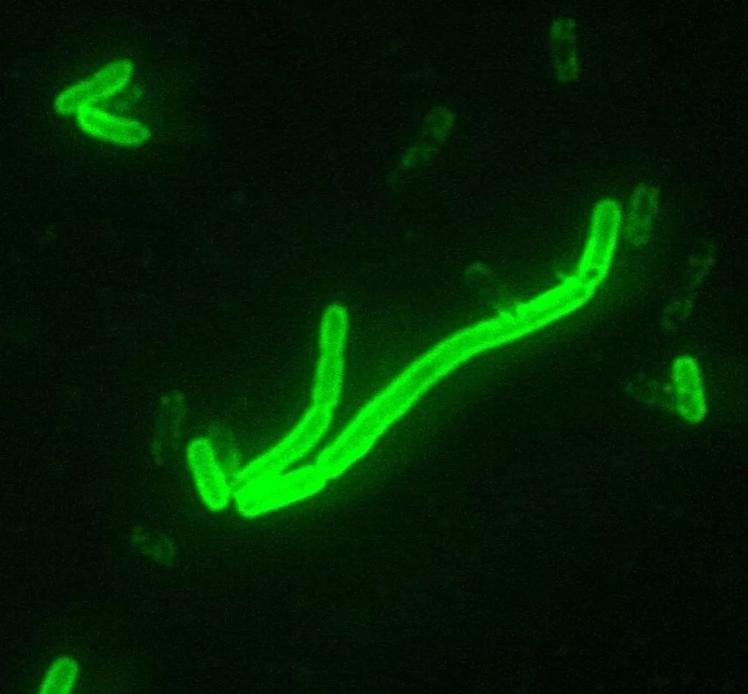

Fluorescent plague rod http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/dbrief/files/2016/06/yersinia_pestis_fluorescent.jpeg

Chinese and German scientists analyzed the complete genomes of 17 strains of Y. pestis from around the world and found that the common ancestor of Y. pestis may have originated in China or nearby regions, as Y. pestis isolated from China contains more genetic mutation sites. In addition, scientists have also found that the lethality of Y. pestis is not innate, but gradually evolved.

Written by | Tang Bo

Editor-in-charge | Zhu Liyuan

According to the Beijing Municipal Health Commission, on November 12, 2019, two elderly couples from Xilingol League in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region were diagnosed with pneumonic plague in Beijing, and no abnormal conditions have been observed in close contacts with the two people, and medical observation has been lifted. On 16 November, another case of bubonic plague was confirmed in Xilingol League, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, and 28 people in close contact with him were isolated and currently have no fever symptoms. Despite successive plague infections, the probability of a plague pandemic is very small. Since the plague has killed hundreds of millions of people in human history, the news has attracted widespread public attention. However, as scientists' understanding of plague and its pathogen, Y. pestis, continues to grow, plague prevention and control has become easier and easier for the public not to worry too much.

1. Once changed human history

Plague is a fierce infectious disease caused by Y. pestis, and its transmission route is mainly based on rat flea bites, droplets, skin wounds, digestive tract infections, etc., and the main clinical symptoms include fever, lymphadenopathy, pneumonia, toxemia symptoms, etc. Depending on the symptoms and the site of onset, plague can be divided into types such as bubonic plague, septic plague, and pneumonic plague.

This is not the first time that plague has occurred in China in 2019, according to the information released by the official website of the National Health commission, in September this year, China has reported 1 case of plague incidence and 1 death case, but it did not cause concern at that time. In addition, in the past ten years, a total of 26 plague outbreaks have been reported in China, of which 11 have died, and the number of cases and deaths has decreased year by year. The incidence of plague worldwide is also decreasing year by year, with only a few countries experiencing plague in recent years. According to the World Health Organization, the number of plague outbreaks in Madagascar reached 2348 in 2017, and 202 deaths, making it the worst plague outbreak in the world in recent years. In fact, the plague has occurred three times in the history of the world, killing hundreds of millions of people.

Since his accession to the throne in 527 AD, Justinian I of the Eastern Roman Empire was ambitious, hoping to restore the glory of the Roman Empire across Eurasia and Africa as soon as possible, and he sent armies around to conquer North Africa, Italy and Spain, but a sudden plague shattered Justinian's dreams. Justinian himself contracted the plague and survived the active treatment of the imperial physicians, but many of his subjects were not spared.

According to the historian Procopius at the time, the plague first appeared in Egypt and other African regions in 541 AD, then spread to Constantinople (present-day Istanbul, Turkey), and then swept across Europe, including England, as well as some parts of Africa and Asia. The infected people first had fever, and then lymphatic swelling appeared at the base of the thighs, armpits and other parts, followed by incurable deaths, and some people in contact with the infected people also fell ill and died, and the number of deaths in the city during the peak period was as high as 5,000, or even tens of thousands of people. This plague outbreak lasted until around 750 AD, causing a total of 25 million to 50 million deaths, reducing the population of Europe by more than half, known as the "Justinian Plague". Some historians believe that the Justinian plague may have been an important cause of the decline of the Roman Empire and the rise of Arab states, and even changed the pattern of the world.

After 600 years of silence, a similar plague pandemic has returned. In the 1630s, China, India, the Middle East and other countries and regions took the lead in the plague, by 1347, the plague through the then maritime hegemony of the Republic of Genoa Kaffa (now in the Ukrainian Crimea), once again swept across Europe, by 1352, the European population has decreased by more than 30%, and caused more than 50 million deaths in Europe, Asia and Africa. In this plague pandemic, in addition to the symptoms similar to the Justinian plague, patients will also have black spots or lilac black spots on their arms or thighs, so they are called the "Black Death". Until the late 18th century, similar plagues continued to occur in Europe, but they were not as deadly as the Black Death of the 14th century.

Sufferers of black disease in the 14th century

https://www.historic-uk.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/great-plague-1665.jpg

The most recent plague pandemic began in 1855 in Yunnan Province, China, and then spread to Guangdong Province, Hong Kong and other places, and the plague also spread along international trade routes to India, California, Australia and other places, until 1959, causing more than 15 million deaths.

The pandemic also allowed humanity to find out for the first time the culprit behind it and find an effective response. In 1894, the Swiss-French physician Alexandre Yersin first discovered from Hong Kong patients that the culprit of the plague was Y. pestis, and scientists later named the deadly bacterium, Yersinia pestis, after Yersinia pestis. Four years later, French doctor Paul-Louis Simond discovered in Karachi that brown rats are the main hosts of Y. pestis, and fleas that parasitize brown rats are the main vectors of the bacteria, and then Simond and his colleagues also used Y. pestis to make inactivated vaccines and attenuated vaccines, which played a role in controlling the epidemic. With the widespread use of antibiotics and the introduction of isolation measures, plague has also been effectively controlled worldwide.

2. Did all three pandemics originate in China?

Since many severe infectious diseases in history have caused heavy casualties, how do scientists determine that these great plagues are plagues? The dna information specific to Y. pestis gave the scientists the answer.

In April 2014, scientists at research institutions such as Northern Arizona University in the United States published a paper in The Lancet Infectious Disease, revealing for the first time that the Justinian plague that occurred in Europe and other places between 541 and 543 AD was the plague caused by the plague bacillus. The researchers found two bodies from a medieval tomb in Aschheim, Bavaria, Germany, and radiocarbon dating showed that the two bodies were dated to 504 and 533 AD, respectively. Scientists isolated specific gene sequences from the teeth of the two corpses, and thus deduced that the Justinian plague was indeed plague, but these strains were not the same as those that caused the Black Death in the 14th century.

As early as 2010, scientists from research institutions such as the Institute of Anthropology of Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, Germany, found the unique DNA and protein characteristics of Y. pestis from human teeth or bone tablets in tombs in Northern, Central and Southern Europe from the 14th to 17th centuries, proving that the outbreak of the 14th century and the resurgence of the Black Death in the centuries after that were also caused by Y. pestis. The following year, Kirsten Bos and others at McMaster University in Canada genetically screened 46 teeth and 53 bones excavated from the East Smithfield Cemetery in London, England, and found plasmid DNA unique to Y. pestis, which was once the burial place of victims of the Black Death who died between 1348 and 1349. The researchers then extracted Y. pestis from five of the teeth and sketched the genome of Y. pestis that triggered the 14th-century Black Death, speculating that the existing Y. pestis was closely related to Y. pestis in the 14th century. The study was published in the journal Nature.

In 2019, two research teams led by the Max Planck Institute for The Science of Human History in Germany analyzed the genomes of Y. pestis associated with the first and second plague pandemics, respectively, and demonstrated that these plague pandemics had multiple deadly strains of Y. pestis at the same time, and that by the end of the pandemic, these deadly Y. pestis had lost some key gene fragments, resulting in a weakening of their infectivity and virality, and the outbreak was controlled.

Where do these Y. pestis bacteria come from? In October 2010, researchers from the Max Planck Institute of Infectious Diseases and the Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology in Germany analyzed the complete genomes of 17 strains of Y. pestis isolates worldwide, and used nearly 900 snp sites to map the phylogenetic trees of Y. pestis, and found that the common ancestor of these Y. pestis bacteria may have originated in or near China, and then spread to all parts of the world through international trade. Because Y. pestis isolated from China contains more genetic mutation loci.

The researchers also speculate that Y. pestis existed in China 2,600 years ago and then spread to neighboring countries and even around the world at different stages through multiple international trade routes, such as Zheng He's fleet may have brought rats suffering from plague to regions such as North Africa and West Asia, causing the plague to subsequently sweep across Europe, triggering the Black Death in the 14th century. The third plague pandemic of the 19th century itself originated in Yunnan Province, China, and the 6th-century Plague of Justinian may also have been linked to the Plague Bacillus active in China.

In 2013, the team again performed snp polymorphism analysis on 133 genomes of 133 Y. pestis isolated from China, Mongolia, the Soviet Union, Myanmar and Madagascar, and found that Y. pestis isolated from the Tibetan Plateau in China had the richest genetic diversity, further speculating that Y. pestis may originate from the Tibetan Plateau in China or nearby regions.

3. The evolutionary path of Plague bacillus

By tracking the genetic information of dna that remains in human remains of Y. pestis, scientists have discovered that the lethality of Y. pestis is not innate, but has evolved step by step. In 1999, researchers at the Max Planck International Genetic Institute in Germany and the Institut Pasteur in France analyzed the genetic information of Y. pestis and other related bacteria worldwide, speculating that Y. pestis evolved from pseudotuberculus bacteria in the soil 20,000 years ago, and obtained two key plasmids (pmt1 and ppcp1) in the process of evolution, which gave Y. pestis the ability to infect mammalian cells.

When did Y. pestis evolve pathogenicity? In 2018, researchers at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany wrote in Nature Communications that Y. pestis only had the ability to infect rat fleas during the Bronze Age about 3800 years ago, so that it could infect mice and humans on a large scale. That same year, Katharine Dean of the University of Oslo in Norway and colleagues studied nine large-scale plagues that occurred in European cities between 1348 and 1813, including Barcelona, Florence, London, Stockholm, Moscow, and Gdansk, Poland, in which 125,000 people died. Rat fleas are generally thought to be the main vector for the transmission of Y. pestis, but Dean et al. came to a completely different conclusion, believing that human ectoplasms (such as body lice and human fleas) were the main vectors of Y. pestis that caused the Black Death.

Plague doctor wearing a bird's beak mask

http://discovermagazine.com/~/media/images/issues/2016/october/plague-doctor.jpg

The earliest record of plague bacillus infecting humans dates back 5,000 years. In October 2015, researchers at the Danish University of Science and Technology and the University of Copenhagen in Denmark genetically analyzed the remains of 101 Bronze-age teeth, and seven of them were detected with specific gene sequences of Bacillus pestis. These teeth are dated from Europeans and Asians between 2800 and 5000 years ago, and the common ancestor of these plague bacteria dates back to 5783 years ago, speculating that these early humans may have also been infected with plague bacillus, but these ancient plague bacteria were less virulent than later strains, making it difficult to cause a plague pandemic. The study was published in the journal Cell, and the first author was Dr. Simon Rasmussen.

In January 2019, the research team with Dr. Rasmassen as the corresponding author once again published the latest research in the journal Cell. Through genetic analysis of Y. pestis, they found from a late Neolithic human tomb in Sweden dating back 4900 years that the owner of a tooth was infected with Y. pestis, which belonged to a young woman about 20 years old. Combining their own and others' research, Rasmassen's team deduced that there were many different strains of Y. pestis in Late Neolithic Europe, which may have led to a significant decline in the population of Europe at that time, and that Y. pestis spread with the trade of humans during the Neolithic period, not because of the large-scale migration of Eurasian populations at that time.

As scientists continue to study the mechanism of action, genetic variation and evolutionary history of Y. pestis, plague prevention and control will become more and more relaxed and effective, and there will be no more plague pandemic tragedies like the 6th, 14th and 19th centuries.

Plate editing | Pippi fish