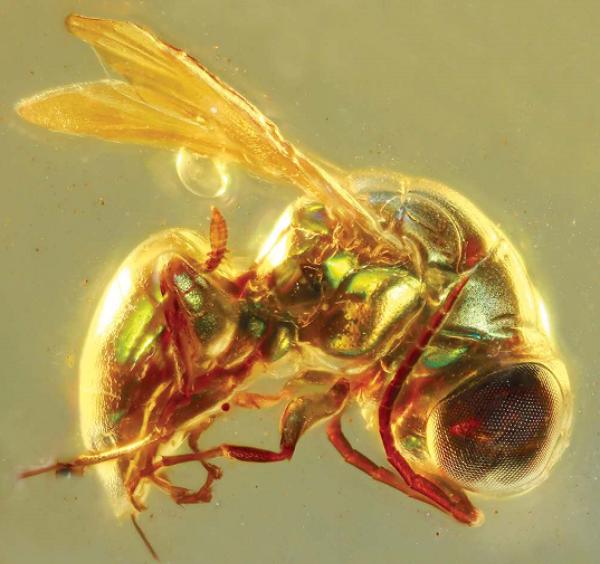

Insects from 100 million years ago in amber fossils. Courtesy of respondents.

From the bright glow of peacock feathers, to the bright warning colors of poison dart frogs, to the white camouflage of polar bears, nature is colorful. However, fossils rarely preserve biological color details, and most paleontological restorations are reconstructed from the artist's imagination.

On July 1, the surging news (www.thepaper.cn) learned from the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences that the research team of the institute has uncovered the secret of the true color of insects nearly 100 million years ago through research. The relevant research paper was published online on the 1st in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B. The paper provides a new perspective on the insects that coexisted with dinosaurs in the Cretaceous rainforest.

A green wasp with a yellow-green metallic luster 100 million years ago.

There are three main sources of color in nature: bioluminescence, pigment color, and structural color. Pigment colors are also called chemical colors, while structural colors are also called physical colors. Structural colors are the purest and most intense colors in nature, usually produced by the action of biological nano-optical structures and natural light. Structural colors in fossils can provide important evidence for visual communication between organisms and the functional evolution of colors. However, it may be that evidence of primitive structural colors in geological history is extremely rare due to the fact that structural colors are easily lost in long-term fossil burials.

Recently, the research team led by Cai Chenyang and Pan Yanhong, researchers of the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, conducted a systematic study of a large number of metal-colored insects in Cretaceous Burmese amber, and found that pure and intense colors can be directly preserved on the surface of a variety of insect bodies. Through the analysis of amber ultra-thin sections, scanning electron microscopy and transmission electron microscopy, it was found that the blue-green color on the thorax surface of a green bee insect is composed of a multilayer of repetitive nanoscale structures, representing a typical and common structural color type, that is, multilayer reflector, and through further optical theoretical model analysis, the reflected wavelength is close to the observed insect color wavelength. It has been confirmed that the color displayed on the surface of the Cretaceous amber insect's body may be the original color.

This discovery directly proves that ultra-micro and nano-sized optical elements can be stably preserved in long geological history, rejects the previous view that insect metallic colors cannot be preserved in Mesozoic fossils, and is of great significance for understanding the evolution of the ecological function of early insect structural colors.

Cai Chenyang et al. selected 35 beautifully preserved insect fossils with metallic luster from mid-Cretaceous specimens (about 100 million years ago), including 3 orders (Hymenoptera, Coleoptera and Diptera), at least 7 families; the vast majority of which belong to the Hymenoptera cynodocetes, a small number of which belong to the Coleoptera cryptoptera, The Wax-Spotted Beetle family, and the Cryptoptera family, and the Diptera waterflies. Most of the insect species have a strong metallic green, blue, blue, yellow-green, or bluish-purple body structure. Through comparative studies with paleozoic and present species, it is found that the corresponding living species of these fossil insects also have similar colors with metallic luster. Therefore, this discovery directly proves that the bright structural color of Mesozoic insects can be preserved. And through ultra-micro analysis of one of the fossil green wasp specimens, it was confirmed that the multilayer reflective film is the direct cause of structural color, which also represents the most common form of structural color in nature.

It is worth mentioning that the seemingly permanently preserved colored metallic structural color in Burmese amber is not unchanged. If any small part of the structure of the amber insect is damaged during the preliminary preparation (such as cutting, polishing and polishing), so that it comes into contact with air or moisture, its color will become a single silver in the short term, but the metallic luster can still be preserved, and this change is irreversible. The discovery of this phenomenon has important reference value for the identification and description of early insect characteristics in order to reveal the formation causes of silver insects in Burmese amber and even other amber.

Researchers believe that the structural color of amber insects has important ecological significance, and the more common green is likely to be a hidden color in a dense forest environment, which can help insects hide themselves from predators. In addition, the possibility of structural colors involved in insect thermal regulation cannot be completely ruled out. Therefore, the structural colors of different colors appear in different species of insects, to some extent suggesting that complex ecological relationships already existed in the forests of the middle Cretaceous Period.

This study was jointly funded by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Association for the Promotion of Youth Science in Chinese Studies.