【Everyone】

Author: Leng Chuan (Special Researcher, Research Center of Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences)

The most heartwarming moment in the history of scholarship is that a scholar with accumulation meets a vigorous era. Tang Tao's turn to modern literary research coincided with such a historical moment.

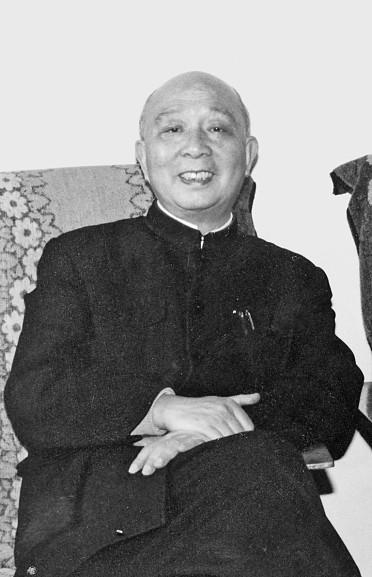

Biography of scholars

Tang Tao (1913-1992), formerly known as Duan Yi, pen names Fengzi, Obscure, Wei Chang, etc. People from Zhenhai, Zhejiang. Writer, literary historian. At the age of 16, he was admitted to the Shanghai Post Office as a postmaster, and began to publish essays and essays in 1933, and participated in the editing of the 1938 edition of The Complete Works of Lu Xun. After the liberation of Shanghai, he was elected as a standing committee member of the postal trade union and the head of the cultural and educational section, and later entered the university and cultural departments. In 1959, he was transferred to the Institute of Literature of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (now part of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) as a researcher. He is the author of "Push back collection", "Haitian collection", "Article Cultivation", "Obscure Shushu", etc., edited "Lu Xun Complete Collection Supplement", "Lu Xun Complete Collection Supplement Continuation", and edited "History of Modern Chinese Literature".

Start with Zheng Zhenduo's last wish

The story of Tang Tao's going to Beijing to enter the field of modern literary research probably begins with Mr. Zheng Zhenduo's last wish. On October 18, 1958, Mr. Zheng Zhenduo, then Vice Minister of Culture and Director of the Institute of Literature of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (now the Institute of Literature of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences), died in a plane crash during his visit. Mr. Zheng had two unfulfilled wishes before his death: one was that he presided over a large-scale ancient book collation project, the "Guben Opera Series" had just come out of the fourth series at this time, and the "Guben Novel Series" proposed by He Qifang had not yet been implemented; the other was to transfer Tang Tao to Beijing and preside over the modern literature research work of the Institute of Literature. Why did Zheng Zhenduo trust Tang Tao so much? I am afraid that this is related to the proximity of the two people's academic philosophies and the experience of cooperation in the left-wing cultural circles under the leadership of the CCP.

Tang Tao, whose real name is Tang Duanyi, is a native of Zhenhai, Zhejiang, who dropped out of school due to his family's poverty in middle school, but was admitted to the Shanghai Postal Administration with hard self-study. Tang Tao's interests are extensive, especially for the miscellaneous works of wild history, and he is deeply influenced by Zhang Xuecheng's thinking of "six classics are all history", and he also has careful speculation on the context of the article. In the early 1930s, he submitted a series of articles in "Declaration and Freedom Talk", which resembled Lu Xun's literary style and quickly attracted the attention of the literary world, and critics surrounded and suppressed it as a new pen name of Lu Xun, and praisers were amazed at the sophistication and calmness of the author's writing, which was a great honor for a young man in his early twenties. Lu Xun himself also noticed Tang Tao, and when they first met, he jokingly said: "Mr. Tang wrote an article, and I was scolded for you." Later, Lu Xun noticed that the young man had a similar reading interest to his own, and realized that under the young man's gentle and cautious appearance, there was a similar sense of enthusiasm and distinct love and hatred as his own. In the limited exchanges, Lu Xun gave Tang Tao extremely frank and targeted suggestions, such as attaching importance to self-study foreign languages, supplementing foreign literature, controlling and adhering to long articles, trying to write a modern history of literature and networks, using realistic concerns to guide and organize the center of gravity and direction of his own literary and historical reading, and naturally including the consideration of current literary activities and personnel choices... Although these suggestions were not fully implemented in that era of change, they undoubtedly helped Tang Tao's improvement a lot. In fact, it was precisely under Lu Xun's suggestion and care that by the time the War of Resistance Broke out in full swing, Tang Tao had grown into a relatively mature fighter in the left-wing cultural camp. For the literary circles of the 1930s, Tang Tao was a witness, and he had a practical understanding of his achievements and limitations, such as the "controversy over the two slogans" that had a far-reaching impact on the literary world and the research circles since then, he had his own understanding and judgment - Chinese has always had the tradition of "knowing people and discussing the world", and he turned to academic research after the founding of New China to understand the characteristics of modern Chinese literature, and the advantages of this kind of witness are unmatched by other researchers. However, Tang Tao did not join the Left League and the CCP at that time, which was also due to the care of the party organization and Lu Xun and others. According to the recollections of Xu Maoyong and others, Lu Xun suggested that there should be no rush to expand the scope of left alliance members, and that some people stay outside the organization, making it easier to contribute to the cause of the left in complex struggles. In order to cope with the mail inspection of the secret agents, the party organizations and the left often asked the progressive people in the post office to put in the materials when the inspection was over and the parcel was sealed when the letters were mailed, and the letters were "deposited and waiting to be collected" to confirm that no agents had found out, and then arranged for someone to collect them. In this process, Tang Tao and others made great contributions. Tang Tao once wrote a short essay, "Comrades' Trust", about how Lu Xun took the risk to protect and deliver Fang Zhimin's letters and manuscripts, saying that "Mr. Lu Xun is not a member of the Communist Party of China, but in the minds of all Communists, he will always be the most trustworthy comrade who can be entrusted with his life"—the same applies to Tang Tao himself during the revolutionary struggle.

Tang Tao and Zheng Zhenduo's contacts became increasingly close in the 1930s. Compared with Tang Tao's prudence and thoughtfulness, Zheng Zhenduo was more enthusiastic and straightforward, and all his love and hatred were fully revealed. Zheng was fifteen years older than Tang and was a veritable elder brother, and the two were getting closer and closer in the course of progressive cultural undertakings. Especially after Lu Xun's death, Xu Guangping, Zheng Zhenduo, Wang Renshu and others presided over the compilation of the Complete Works of Lu Xun in the name of the Fushe Society, such a fruitful work, such a tight time, all the reviewers are embracing the love of Mr. Lu Xun volunteer work, Tang Tao is one of them. Every day after busy postal work, he came to the editorial board to silently proofread, and this experience was also the beginning of Tang Tao's future work on the compilation and research of Lu Xun's works. In 1944, when the news reached Shanghai that Lu Xun's Beiping collection was about to be sold, the most powerful person to call for it was Mr. Zheng Zhenduo, and it was Tang Tao who was ordered to go north to negotiate with Zhu An to prevent the sale. During this trip, Tang Tao really saw the dilemma of Zhu An and others' lives, heard his appeal that "I am also a relic of Lu Xun, and you must also save me", and also thoroughly saw through the indifference and miserliness of Zhou Zuoren, who was stranded in Beiping in the name of "supporting the elderly mother and widow". As some researchers have noticed, Tang Tao's literary temperament is actually between the Zhou brothers, intellectually, he admires and follows Lu Xun's fighting spirit, while literary tastes are more focused on Zhou Zuoren's soothing and calmness because of his temperament. The trip to Peiping was an emotionally watershed. Tang Tao's "Tao" character, the original meaning of "bow clothes", not only has the meaning of introverted peace, but also has the passion and sharpness hidden in it, under the inspiration of the national righteousness, he is more and more close to Lu Xun's perseverance and enthusiasm, Zheng Zhenduo's love and hatred.

In line with Zheng Zhenduo, there is also the vision and enthusiasm of the two for literature. Mr. Zheng's deeds of rescuing documents for the nation during the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression are well known, and Tang Tao, the "little brother", is also silently contributing his own strength. At that time, it was reported that in the fallen Shanghai, only two people were trying their best to collect books, and the big one was Zheng Zhenduo, all kinds of orphan books, whether it was an individual pouring out his financial resources or relying on social forces to provide support, he always tried every means to buy them so that they would not be destroyed by war and lost overseas; the small hand was Tang Tao, limited by financial resources and the social relations that could be mobilized, and his focus was not on rare books, but on periodicals and books of new literature. At that time, a large number of new literary books and periodicals flowed into the waste paper collection station, and Tang Tao often soaked in the waste paper collection all day, completely relying on his own food and clothing, using only two burnt cakes a day to fill the hunger, from which a large number of periodicals and books were rescued, such as the complete set of "New Youth", "Novel Monthly", "Modern Review", "Literature", some "Enlightenment" supplements, "Xue lantern" supplements, Beiping's "Morning News", "Beijing News" supplements, etc., as well as the first edition of a large number of new literary books. Due to the national government's book inspection system, some books and periodicals are banned from publication, and occasionally the outflow is an orphan book; some bookstores have weak financial resources, a single distribution channel, a small number of books printed, a narrow scope of sales, and a very limited number of books that can be retained - it seems that all of them are contemporary publications, but the scarcity of literature and the urgency of rescue are actually not weaker than the search and purchase of ancient books. Earlier, when Zhao Jiabi presided over the compilation of the New Chinese Literature Series (1917-1927), the collection of bibliophile Ah Ying ensured the smooth development of this work. Tang Tao, on the other hand, was another person after Ah Ying who had a conscious awareness and practical achievement in the preservation and screening of new literary books and periodicals. It is precisely in this large-scale data rescue work that Tang Tao's literature ability and version awareness are far ahead of his contemporaries.

Zheng and Tang not only have the enthusiasm to receive books, but also have a common understanding of the value of literature. Zheng Zhenduo wrote the "History of Chinese Folk Literature", printed the collection of folk songs earlier in China, devoted himself to the collection and collation of miscellaneous dramas and Dunhuang variations, and also published atlases such as "Beiping Notes" with Lu Xun. After the victory of the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, he began to write, in addition to attaching importance to the exposition of traditional philological values, he also tried his best to preserve the relevant historical records, and tried to preserve the information of the times and humanistic feelings attached to each book, and the broader literary concepts he adhered to were very similar to those of Zheng Zhenduo and others. The aforementioned post office literature transmission work, Tang and Zheng have a long-term cooperation. According to their close friend Liu Zhemin, during the fall of Shanghai, there were more than 300 correspondence between Zheng Zhenduo and the bibliophile Zhang Yongni alone, all of which were related to the rescue and collation of documents, all of which were sent by Tang Tao on their behalf. With more than three hundred emails, Tang Tao's risks can be imagined. The friendship and trust between Zheng Zhenduo, the eldest brother, and the little brother Tang Tao, and their academic commonality and understanding were firmly established in the trials of China's revolutionary struggle and in the exploration and understanding of modern Chinese scholarship.

Data picture of "History of Modern Chinese Literature" edited by Tang Tao

The establishment of the Institute of Literature and its exploration of the academic path in China

The Institute of Literature, of which Zheng Zhenduo is also the director, was established in February 1953. Before the institute was transferred to the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, it was successively affiliated with Peking University and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, but the determination of its work policy and the management of senior researchers were always directly responsible for the Central Propaganda Department, especially after 1958, the politics, ideology and business of the Institute of Literature were directly led by the Central Propaganda Department, and the work it engaged in was incorporated into the national medium- and long-term scientific research and ideological planning. The systematic research on the institution has just begun, but researchers have keenly noticed the ups and downs of the scientific research strength of the Academy of Social Sciences system, the writers association system and the university system after the founding of New China. To put it simply, with the adjustment of faculties and departments in 1952, the most core social scientific research force in New China was not in colleges and universities, but concentrated in the Academy of Social Sciences and the Writers Association, and this situation did not undergo a fundamental change until the 1990s. According to Wang Pingfan's recollection, the guidelines and tasks for the establishment of the Institute listed in the "Plan for the Institute of Literature" are: "From the viewpoint of Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought, we will conduct step-by-step and focused research, collation, and introduction of the development of Chinese and foreign literature from ancient times to modern times and the main works of its major writers." "The composition of the personnel of the institute mainly includes two parts, one is that such a famous artist as Zheng Zhenduo, who has achieved recognized academic achievements, such as Yu Pingbo, Wang Boxiang, Yu Guanying, Sun Kaidi, Qian Zhongshu, etc., and the other is the intellectuals from Yan'an who have a good Marxist education, such as How Qifang, Chen Yong, Mao Xing, Zhu Zhai, Wang Liaoying, and so on. As for the specific work, it was determined at the end of 1957 that the country was second, The seven tasks to be accomplished during the Third Five-Year Plan are described in the most detail: 1. Study the problems in our current literary and art movement, make frequent comments, and regularly sort out some materials; 2. Study and compile a multi-volume history of Chinese literature including new research results and minority literature; 3. Compile some anthologies of Chinese literature and reference materials related to literary history; 4. In the field of foreign literature, study the literature of major countries, and compile some collections of papers according to the times as a preparation for the future compilation of foreign literary history; 5. Compile a series of books of masterpieces of foreign literature in Chinese translation Each work is crowned with a preface to help the general reader understand and appreciate; 6. Study literary and art theory and compile a more popular literary and art science that combines the actual Chinese practice; 7. Compile a series of books on Chinese translation of foreign literary and art theory.

In these seven tasks, literary and artistic reviews and literary history are the focus, and the latter should start from the collection and collation of materials, and the aforementioned "Guben Opera Series" was photocopied and published by Zheng Zhenduo and others in 1954, which is the basis for the "great literary history" and "academic literary history" advocated by literature since then. Transferring Tang Tao into the Institute is also a measure that is in line with the work ideas of the Institute of Literature. Previously, he has achieved outstanding results in the compilation and identification of Lu Xun's works, the writing of books and words has also received widespread attention from researchers, and the commentaries are even more beautiful, as a researcher with outstanding data skills, Tang Tao entered the Institute of Literature, which means that the kind of academic ideas that emphasize historical materials, heavy documents, and also emphasize the guidance of Marxist-Leninist theory have penetrated from the field of ancient literary research to the discipline of modern literature.

From the perspective of the background of the times, Tang Tao's transfer to the Institute of Literature coincided with a joint point in the academic transformation of New China. At the beginning of the founding of New China, the compilation of various types of textbooks had strong traces of the "Soviet model", and the works of theoreticians Zhdanov and Pydakov and Timofiev's "History of Soviet Literature" gave Chinese scholars who explored modern literary textbooks an example to imitate; at the same time, due to the highly homogeneous nature of modern literary history and modern revolutionary history, the earlier popularization of "The History of the United Communist Party (Brazzaville)" is also an important reference book for literary researchers. Wang Yao's Manuscripts of the History of New Chinese Literature, published in 1951, can be seen to a large extent as the product of the combination of modern literary investigations begun by Zhu Ziqing and others and the writing of Soviet-style textbooks. Wang Yao takes the theory of new democracy as the basic logic for expounding the occurrence and development of modern literature, and coordinates the literary periodization with the political period as much as possible; in each time period, the development of different literary styles is introduced in different categories. The "New Chinese Literary History Manuscript" is a pioneering work in the compilation of modern literary history, and it is precisely because of the first trend that the volume of the writers' works involved has an incomparable advantage in subsequent works. The works of Zhang Bilai, Ding Yi and Liu Shousong, which appeared one after another in the mid-1950s, moved closer to the Soviet-style template, basically continuing the model of "general theory + chapters", "ideological trends + stylistic categories", and "key writers + ordinary writer groups" in the history of Soviet literature. In these works, a large number of revolutionary history narratives are used instead of literary style interpretation and analysis, which invisibly lowers the threshold of literary history writing as a scientific research work, making it possible to copy in batches.

Since then, the compilation of literary history has entered the "Great Leap Forward" state, and students in some colleges and universities have simply thrown away experts and professors to write textbooks by themselves, the most famous of which are the "History of Chinese Literature" written by the 55th grade students of the Chinese Department of Peking University and the "History of Chinese Folk Literature" and "Lecture Notes on Chinese Literature" written by students of the Chinese Department of Beijing Normal University. These works have a very serious tendency to simplify, conceptualize, and vulgarly politicize, and Mr. Zheng Zhenduo's "Illustrated History of Chinese Literature" and "History of Chinese Folk Literature" have become one of their key criticisms. In mid-1959, at a seminar jointly held by the Institute of Literature, the Writers Association, Peking University, and Beijing Normal University, He Qifang's speech was extremely eye-catching. Under the title of "Several Issues in the Discussion of Literary History", he clearly put forward that a literary history should have three basic characteristics: first, accurately describe the facts of literary history; second, summarize the experience and laws of literary development; and third, properly evaluate the works of writers. In her speech, He Qifang euphemistically but clearly criticized the above-mentioned literary history for trying to use the formulas of "realism" and "anti-realism" to summarize the shortcomings caused by complex literary phenomena, and took the 55-level literary history of Peking University as an example, and specifically explained the problems of conceptual confusion, confusion of evaluation standards, separation from history and harsh ancients, simple application of Marxism-Leninism expressions, and lack of necessary historical common sense. It was also at this conference that He Qifang mentioned that the Institute of Literature also has a literary history writing program, but its goal is academic.

With the loosening of Sino-Soviet relations in the late 1950s, the compilation of a modern literary history with Chinese characteristics was put on the agenda. The relevant leaders of the competent departments proposed that the positioning of the literary research institute should focus on "improvement" rather than "popularization", requiring the literary institute to "vigorously engage in materials" and establish the most complete data reserves from ancient times to the present. In early 1960, after the Central Propaganda Department decided that the Modern Group of the Institute of Literature was responsible for compiling the "History of Modern Chinese Literature", this work was not rushed, and the members of the Modern Group studied and commented on more than a dozen literary histories compiled by colleges and universities in various places from 1958 to 1960 in accordance with the requirements, and made a comprehensive census of the development of the discipline. More importantly, with the direct help of Zhou Yang, then deputy director of the Central Propaganda Department, Tang Tao invited Mao Dun, Xia Yan, Luo Sun, Li Shu, Tao Ran, and other witnesses of the modern literary movement to come to the forum, or introduce the historical facts of the literary movement they knew, or make suggestions on how to write a literary history. What this group of writers and scholars talked about deeply shocked the young people in the writing group. For example, Fan Jun, who was still a young scientific researcher at that time, said in his recollection that Xia Yan on the one hand frankly stated that the "proletarian literature" advocated in the 1920s and thirties had made a "left-leaning" mistake, and on the other hand, he also said that the left-wing movement could flourish under the harsh rule of the Kuomintang and should be analyzed dialectically in the compilation of literary history; historian Li Shu was extremely enthusiastic about Li Jieren's "big wave" trilogy, and this work actually did not attract the attention of the research circles after the founding of New China; Luo Sun reminded young scientific researchers. Literature and art serve politics, but "success is also Xiao He is also Xiao He", how to take into account the relationship between the two needs to be carefully considered... These conversations have greatly expanded the horizons of the writers, enlivened their thinking, and made them realize the huge historical and cultural content of modern literature in the past thirty years—which shows the academic accomplishment actually possessed by the Chinese Communists, and also reflects the political connotation and historical character of modern literature from another angle.

Tang Tao as a literary historian and the establishment of the "threshold" for modern literary research

In the autumn of 1959, Tang Tao was transferred from Shanghai to the Institute of Literature, serving as a researcher and head of the modern literature group. At the beginning of his entry into the institute, he expressed his wish to He Qifang, one is to write a biography of Lu Xun, and the other is to independently write a modern literary history with characteristics. Tang Tao's experience and knowledge structure are different from those of intellectuals such as Wang Yao, Ding Yi, and Liu Shousong, who have been growing up in colleges and universities, and his keen artistic perception and literary talent as a writer, his proficiency in modern literary periodicals and works as a bibliophile, and his understanding and consideration of literary history as a witness to modern literature have made him the perfect candidate for writing the history of modern literature. Different from the basic model of "ideological trends + style" that was popular at that time, Tang Tao had his own perspective, as he mentioned many times in the 80s, "According to my vision, it is best to write mainly in literary societies, writing genres and styles." However, personal history was not mainstream in the fifties and sixties, and the Institute of Literature was an exemplary unit, and soon the idea of individual history writing gave way to the collective program of the Institute of Academic Literary History, but as mentioned above, the vision and ambition of this premature project in the preparatory period were still heartwarming.

But things soon changed again. In 1961, Zhou Yang was appointed to focus on the construction of liberal arts textbooks in colleges and universities, and the writing of modern literary history was the top priority, and tang Tao and the backbone members of his team were undoubtedly the most trusted candidates. Both He Qifang and Tang Tao himself, after a brief hesitation, their principle of party spirit made them resolutely turn to the writing of the History of Modern Chinese Literature as a textbook for liberal arts. Just as Huang Xiuji, who was engaged in the study of the history of the discipline earlier, said, in order to compile this set of teaching materials, the strength of the state's investment is unprecedented. Tang Tao was the editor-in-chief of the book, and Wang Yao, Liu Shousong, Liu Panxi, and others who had previously made achievements in writing literary history all participated, and the young and middle-aged scholars who participated in the writing of this book, such as Li Wenbao, Yang Zhansheng, Zhang Enhe, Cai Qingfu, Lü Qixiang, Chen Ziai, and Wang Dekuan of the Beijing Normal University, Fan Jun, Lu Kan, Wu Zimin, Xu Zhiying, Xu Tixiang of the Institute of Literature, Yan Jiayan of Peking University, Wan Pingjin of Xiamen University, and Huang Manjun of the Central China Normal College, most of them became key figures in the discipline in the future. Textbooks require knowledge and stability, it does not have to be the most exploratory and pioneering, but it must be solid and accurate, and the evaluation of writers' works must withstand scrutiny and convey true historical information to the greatest extent. In other words, from the perspective of writing history, this literary history provides us with a bottom line, or the "entry threshold" that modern literary research should have.

According to the recollections of many participants at that time, Tang Tao, as the editor-in-chief, and the team members jointly established five principles of writing: First, first-hand materials must be used, and the works should be checked in the journals originally published, at least according to the first edition or early prints, so as to prevent the reversal of the attack and spread falsehoods. Second, pay attention to writing the atmosphere of the times, literary history is written in the context of historical evolution, only by mastering the horizontal appearance of the times, can we write about the development of history. Other articles on the same issue contained in the press should be fully utilized. Third, try to absorb the existing research results of the academic community, and even if the personal opinions are incisive, they will not be written into the book until they are recognized by the public. Fourth, to recount the content of the work, to strive for conciseness, not to violate the original intention, but also to avoid lengthy and procrastination, which is a kind of artistic re-creation in literary historians. V. Literary history adopts the "Spring and Autumn Brushwork" as much as possible, and praise and criticism must be revealed from the narrative.

In addition to the third article, which is a conservative choice that textbooks have to have, the other four have clear practical pertinence, and also reflect the determination of Tang Tao and others to establish technical standards for modern literary research: familiar with the original periodicals and returning to the historical field means the return of the historical character of literary history compilation; from the atmosphere of the times when writing works to combing the historical context of clear literary development, it is Tang Tao who repeatedly reminds young researchers of the progressive research logic of "points, surfaces, and lines", which not only echoes the exploration of the law of literary and cultural development at that time. It also makes every judgment valid. The emphasis on the Spring and Autumn Brushwork avoided simple and crude political criticism and was a rejection of the popular way of compiling "taking history with arguments" and even "replacing history with arguments". It is precisely because of adhering to the above principles that this work has the effect of clearing the source in many aspects, such as the opening article on the May Fourth literary revolution, the necessary affirmation of the contributions of Hu Shi and Chen Duxiu, and the investigation of the ideological development of Li Dazhao and Chen Duxiu in those years, and the characterization of the May Fourth Movement, these problems are handled rationally and well-founded, showing great academic courage; for sensitive topics such as the controversy of the two slogans, it also truthfully describes the process of controversy and the impact of positive and negative aspects, and adopts the "coexistence" advocated by Lu Xun. This reflects the compilers' in-depth understanding of the party's policy of the anti-Japanese national united front. To the greatest extent, this work organically unifies the principles of party spirit and the spirit of historians, and is both clear-cut and well-founded, and the wording is tactful, leaving readers with plenty of room for reflection and deliberation. In particular, the two chapters of Lu Xun, written by Tang Tao himself, are the chapters with the highest level in the whole book, and they can best reflect the author's theory from history and implicitly contain the style, even if they are read now, they have a sense of enduring renewal. The concepts on which academic research is based are varied, but the scholarship itself is never outdated.

As a writer of "Article Cultivation" and "Creative Ramblings", tang Tao, who is also a stylist, he emphasizes historical materials, but opposes the accumulation of materials, requiring literary history writers to repeat works with concise and beautiful brushstrokes, criticize and praise, and use words that can withstand chewing. Many people have recalled Tang Tao's emphasis on writing, such as Wu Zimin, Lan Dizhi, Yan Jiayan said, the setting of a text title, the beginning of an article, changing six or seven times is extremely common, the text or large straight writing, or finely crafted, sprinkled light as if the clouds flowing water, occasionally four or six pairs, ancient Meaning Senran, the people who pay attention to are in the natural flow of the literary atmosphere, always deliberately operating, but also strive to find no trace of the realm. At present, we emphasize the "research" of scholarship, the ancients are relatively more important is the weight of "article", in Tang Tao, he is intentional to integrate the two, such as the long paper "The Artistic Characteristics of Lu Xun's Essays" written in 1956, which can withstand Guo Xiaochuan's recitation at the memorial conference, the performers are full of emotion, the text read is round and smooth, and the listener is amazed - this pursuit of academic papers is a special contribution of Tang Tao, and its intention is high, even in the present, it is almost luxurious.

The fate of Tang Han's literary history is too bad to be repeated. Its formal publication and popularization have already been after a new period, when the discourse of modernity has replaced the previous single revolutionary perspective, and this work, which embodies the countless painstaking efforts of Tang Tao and his assistants, is destined to be only an "intermediate object of history". However, its significance to the discipline of modern literature goes far beyond the text itself, from a certain point of view, the compilation of this book can be regarded as the first generation of scholars and the second generation of scholars after the founding of New China in the academic methods and knowledge cultivation of the most concentrated exchange, especially the emphasis on first-hand information and systematic reading, so that the young scholars involved in this project have a practical understanding of the family background and research methods of modern literary disciplines, and popularized in the new era, "reading journals" has become a compulsory course for graduate students majoring in modern literature. The data collation and community school research ideas valued by Tang Tao have also become the most reliable resources when the discipline starts again in the 1980s, the former has Ma Liangchun, Xu Qixiang and Zhang Daming presided over the large-scale document project "Compilation of Chinese Literary History Materials", and the latter has Yan Jiayan's "History of Chinese Novel Genres" and Yang Yi's "History of Modern Chinese Novels" and other fruitful achievements. From the reform and opening up to the mid-to-late 1980s, in less than a decade, the achievements of the modern literary research community have shown a spurt trend, and they have quickly caught up with and surpassed the achievements of overseas sinology circles in terms of content volume and depth and breadth of literary understanding, and it can also be seen that the great potential contained in the academic thinking of Tang Tao and others can also be seen.

When we discuss the value and contribution of Tang Tao's academic research today, the focus is not on the distribution of honorary rights. We should note Tang Tao's upbringing in the progressive cultural undertakings led by the Communist Party of China, the mission of the institute of literature where he works, and the trust and support of the competent authorities. Tang Tao regards the writer's works as the "point" of interpreting the times, in fact, he himself is also a point, we should interpret the influence of the times from him, sort out how he combines his personal academic accumulation and interest with the grand proposition of exploring China's academic path, and draws resources from tradition and finds support from reality for modern literary research.

Guangming Daily ( 2021-08-02 13 edition)

Source: Guangming Network - Guangming Daily