Today, the world of life is full of brilliant colors. The male peacock's feathers are colorful and used for courtship; the poisonous mushroom warns the hungry ghosts with bright and exaggerated colors: I am poisonous, don't touch me! The bright colors of butterflies combine courtship and deterrence.

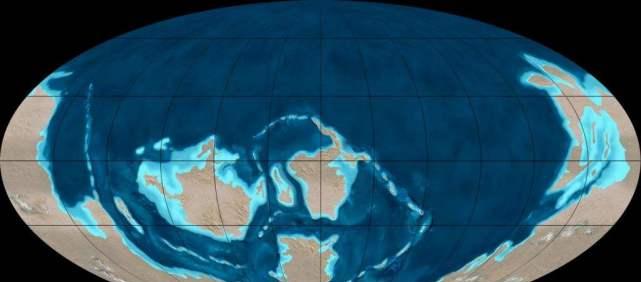

Life was born on Earth about 3.8 billion years ago, and it wasn't until the early Cambrian period, more than 500 million years ago, that pioneers of various complex types of organisms emerged. So, when did the colorful colors of life begin? So far, people know very little about the body color of prehistoric creatures, but the research of a British paleontologist has opened a window for us to glimpse the color of prehistoric organisms.

<h2 class= "pgc-h-arrow-right" > bright light on the feet of the mesozoites</h2>

Please follow me on an imaginative journey to visit this flourishing paleontologist. The British Museum of Nature in London has a 250-year history and a collection of over 70 million pieces, making it one of the world's top museums. Dr. Andrew Parker of the museum has been studying cambrian fossil organisms for many years and has achieved fruitful results.

Parker said: "For a long time, biological fossils were buried deep in the rock, and after withstanding high temperatures and high pressures, it was almost impossible to retain the colors that organisms originally possessed. The color of the fossils we usually see is only the color of the rock formed after the components of the biological remains were replaced by minerals. However, because of a chance luck, I encountered the bright colors of Cambrian creatures. ”

In 1993, Parker participated in a collaborative scientific project by multinational scientists to investigate marine life around Australia, where Parker studied a class of marine animals called mesozoans.

Mesozoans are tiny crustaceans shaped like shrimps, no more than a few millimeters long, and their bodies are wrapped in two hard shells. The body of the mesozoite is so small that after being salvaged from the ocean, the detailed structure of its body can only be seen under a microscope; their shell is hard and slippery, and it is difficult to flip and fix it with tools. Parker said: "Despite the difficulties, the observation of mesembles inspired my later research. ”

One day, when Parker was observing the mesozoites in the laboratory of the marine survey vessel, he saw the mesozoites' bodies glow in an instant. Parker thought his eyes were glazed over, and he rubbed his eyes and continued to look through the eyepieces of the microscope. Many observations since then have proved that this is not an illusion, and that the mesembran can indeed emit a green light. Recalling the scene now, Parker is still excited, saying: "The mesozoite's body can emit light, which is not mentioned in any literature, but I thought it was important at the time and explored it further." ”

Upon further observation, Parker discovered that the mesozoite's green glow was emitted from fine hairs on the feet. Like the shrimp and crabs we often see, the mesembranous feet and fine hairs on the feet are wrapped in chitinoskeletons, and the light is emitted from the surface of the exoskeleton. After bringing the mesozoites back to the British Museum of Nature, Parker performed a detailed analysis of the specimens with an electron microscope. He found that the surface of the fine hairs on the feet of the mesomorphs had a special structure, which is called a "light grid" in physics. Rasters reflect light and produce a variety of colors through the interference and diffraction of light. As a result, Parker had a certain conviction in his heart: the green light on the mesozoite's foot must have been emitted by the light grid on the foot!

Grating of Cambrian fossils

The grating structure of the mesomorphic body surface gave Parker great inspiration. "Unlike pigments, colors produced by the structure of objects, like gratings, can be preserved in fossils," he said. A butterfly that dances in a flower bush, the color of its wings is also produced by the structure. If prehistoric creatures also had structural colors, they must be found in the fossils they left behind. ”

With this in mind, Parker immediately took action, first visiting the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., which houses a huge collection of biological specimens and paleontological fossils. After analyzing the Cambrian era fossils in the museum, Parker actually got his wish and found three fossils with grating structures. The Smithsonian Museum's collection of Cambrian fossils from the Burgess Shale in the Canadian Rockies, which lived in shallow seas more than 500 million years ago, were the precursors of modern biology created by the famous Cambrian explosion.

The first fossil with a grating structure found by Parker was called Wiwaxia. The body of the Vevasi worm is only about 5 centimeters long, and it is more like two rows of thorny pebbles than an animal. Parker found the grating structure from the scales on the surface of its body and the surface of the thorns on its back, and when it was alive, its body must have shone with colorful brilliance, crawling slowly on the bottom of the sea.

Next up is Marrella. The shape of this bug resembles the famous ancient creature Trilobite, but the most exaggerated part of its body is the pair of feet and antennae. It is only about 2 centimeters long and lives near the bottom of the sea, sometimes crawling and sometimes swimming. The surface of its feet and antennae is covered with a grating structure, indicating that the body of this small animal is also colored when it is alive.

Finally, there's the Canadian worm (Canadia). The animal is about 2 centimeters long and covered with fine fuzz, like a caterpillar on a tree. Parker found that its slightly hairy surface was filled with a grating structure, indicating that when the animal was alive, its fluff must have shone like a filament lamp.

With a different idea, Parker discovered the grating structure of the fossil's surface, proving that these ancient creatures had brilliant colors. Parker is still continuing to search for the grating of Cambrian creatures, and he will present us with a more colorful world of Cambrian marine life.

The colors of living things have practical functions. A few years ago, while studying mesozoites off the coast of Australia, Parker discovered that the light on the mesozoites' feet was used to attract the opposite sex. When male and female mesenchymals meet, the males first circle around the females while boasting to the females with their glowing feet, just as a male peacock shows beautiful feathers to the females. Next, if the male and female are in love, they hug each other and begin to mate.

Parker argues that since many creatures today use color as a medium to communicate, the brilliant colors of sea life in the Cambrian era must have also played two basic functions, namely courtship and avoidance. Parker said: "The Cambrian era was the oldest era when evidence of biological color was found in fossils, and the creatures of that time must have used color as one of the means of communication, just like the creatures of today." The Cambrian period not only saw a great biological explosion, but it was also the era when life first communicated with color. ”