Beijing Youth Daily

"Left-Handed Women"

"The Soil of Bones"

Recently, the Swedish Academy of Letters announced the winners of the 2018 and 2019 Nobel Prizes in Literature, one of whom is the austrian writer Peter Handke, who has long been famous in the world, and the other is the Polish female writer Olga Tokarczuk. Interestingly, the two have something in common on many levels, most notably, they are both European writers and both love and know about mushrooms (not sure why). However, for the author, what I want to talk about most is that both of them have the experience of film screenwriting, and the works they directly participated in the screenwriting have received praise at the three major international film festivals in Europe. Through these films, we may be able to glimpse some aspects of the creation of the two writers.

Confusion and drift:

Under the Berlin Sky

"The Anxiety of Goalkeepers When Faced with Penalties"

"Wrong Move"

It is not a rare thing that the representative works of Nobel Prize writers have been adapted into movies, far from saying that the famous Spanish director Pedro Almodóvar adapted a series of works by 2013 Nobel Literature Prize winner Alice Monroe to create the business card "Juliet Tower"; the representative work of 2017 Nobel Literature Prize winner Kazuo Ishiguro, "Traces of Gone to Japan", was also put on the screen by director James Ivory and his screenwriters earlier. In these cases, the original author often does not get involved in the process of adapting the literary work, but this time the two writers who won the award are different, they can be said to be directly involved in the creation of the film script from the beginning, and we can even think that these two are not only novelists, but also film screenwriters.

In the case of Peter Handke, his collaboration with the famous German director Wim Wenders dates back to Wenders' debut feature film in the early 1970s, and has continued until 2016's new work Alanjuez's Good Days. However, due to the different depths of involvement, the results of the two people's cooperation often look different, and the textual meaning is not very different.

To put it simply, the co-creation of the two can be divided into three main types: the first is Handke's limited assistance to Wenders, but in fact, he is not deeply involved in the process of creating film scripts, the most representative example of which is the film history masterpiece "Under the Berlin Sky" (1987) that fans are familiar with. This was also confirmed in an interview with the duo at MOMA in New York. Wenders once said: "Peter magically imagined and guessed the film I wanted to make, and like my archangel helped me, completed these scenes that he didn't even know had been filmed." That is to say, Handke provided some dialogue and ideas, and the construction of the overall structure of the script and the writing of the main content were completed by Wenders himself before and during the shooting. In fact, viewers who have seen this film will understand that there is a great tension between the warm humanity expressed in "Under the Berlin Sky" and the creative style of Handke's novels, which is probably why Handke does not think that "Under the Berlin Sky" has any representation in his literary works.

The second category was when Peter Handke wrote original screenplays or adapted his novels into screenplays, while Wenders made his screenplays into films, including Wenders' feature-length debut, The Anxiety of Goalkeepers When Faced with Penalties (1972). In this film, a goalkeeper is fired, then kills a woman for some inconspicuous reason, and then embarks on a "casual" escape. The Wrong Move (1975, the famous "Highway Trilogy" Part II) three years later is also a very obvious example, the film is very loosely adapted from Goethe's original book, Handke almost only borrowed Goethe's central ideas and some of the most basic ideas, and then completed the script in his own language and way. Putting the two films together, we find very similar themes and internal motivations: they both show a certain kind of behavioral abnormality, as the title "Wrong Move" (aka "Wrong Way") suggests, and sometimes the protagonist completely and somehow does a wrong thing that completely changes the course of their lives, as if each action prompts the protagonist to fall into the abyss of self-excavation, forming a chain and cycle of wrong things.

Referring to "The Goalkeeper's Anxiety in the Face of a Penalty," Wenders said the film "is a film that only shows what is visible, it doesn't even show any emotion, it's very restrained about emotions." It deals only with the surface of things." Unlike traditional road movies, and even unlike the other two in the "Highway Trilogy" (both written by Wenders himself), the protagonists in several of handke's films that he directly participated in writing basically did not get new experiences and growth after a journey, but continued to sink. This is not only a critical creation of the road film genre at the text level, but also an objective record and expression of the living conditions of ordinary people in West German society at that time.

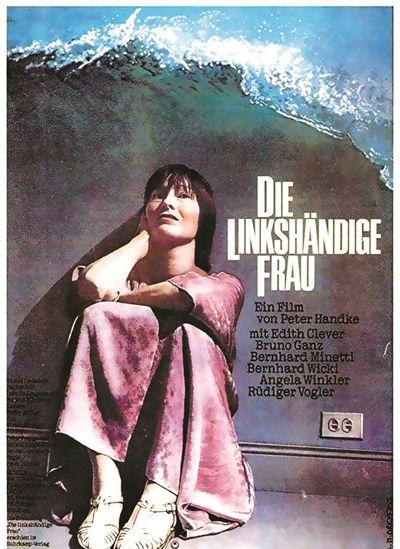

Female and independent

There is a third genre of co-creation between Wenders and Handke, in which Handke becomes a veritable nucleus and protagonist – he adapts his novel into a film as a director and screenwriter, and Wenders becomes his producer. In his work "Left-handed Women", the heroine resolutely leaves her husband who has just returned home from a business trip and begins a new life with her children. In the process, she began to face various challenges, and her body and mind were gradually on the verge of collapse in a state of loneliness. Until the end of the film, all the characters who have ever appeared in the film reappear and then all leave, and the heroine who witnessed all this returns to the house and says to herself, "I have not betrayed myself, and no one can insult me anymore." It seems difficult for us to actually see from this film how people have "insulted" her, but it is conceivable that the heroine is tired of endless waiting and waiting, and realizes that she must rely on herself and overcome herself after a long period of solitude before and during the film. Peter Handke concludes the film with the phrase "The man who creates space for himself" swears the importance of a certain independence of personality (both for the heroine of the film and for the writer himself) – which also reminds us of how the real-life writer Handke supported Yugoslavia and Milosevic, how to return the world's most cherished Bichna Prize, how to call himself "a bastard when he is not writing"... For him, it is only when people realize their existence and hold fast to their own views and behaviors that the whole world will open up to them and reveal their true faces.

It is interesting to note that Handke's film clearly consciously features women as protagonists, which reflects the author's understanding of the status of women in West German society and even in human society as a whole at that time and the problems of subjectivity they faced. If Handke is to express the dilemma faced by a woman through inner struggle, then the female writer Olga Tokarczuk has achieved an impact and subversion of the existing social structure in Poland with a more violent external action in her screenwriting work.

Feminism and dreams

In the Polish film "Soil of bones" (2017), written by Tokarczuk and won the Arfrebauer Prize and the Silver Bear Award at the Berlin Film Festival, the heroine suddenly found her dog missing after waking up one morning, and in the process of constantly searching for her dog, she found herself inexplicably hindered by various forces in the town. Some critics have a deep misunderstanding of the film, simply seeing it as an environmentalist film, so it is difficult to agree with the heroine's killing of animals. But in reality, the disappearance of the animal is only an inducement, and the heroine is not only an animal protectionist, but also rebels against not only the people who kill the animal, but the lower level, the male-dominated, airtight, and exclusive power world of Polish society. Interestingly, the hunting and church scenes in the film are also reminiscent of danish director Russ von Trier's two works, Breaking the Waves and This House I Made, making it easier for us to appreciate how violence asserts its power and transforms it into suffocating social power.

Of course, "The Land of Bones" only reflects one aspect of Tokarczuk's literary creation, and Tokarczuk as a feminist and director Holland are not "enemies of men". In fact, after all the dust settles at the end of the film, the heroine and her husband and a young couple flee the town in the dark, build a non-blood family deep in the unknown forest, and return to the idyllic life – although we don't know if such a bright and extraordinary scene is real. Maybe it's just a dream of independence and equality, but for Tokarczuk, at least it's worth the effort.

Discipline and language

Casper

As mentioned above, there is a very powerful scene in the Land of Bones, where in the church, the priest teaches children that they can and should kill animals according to the Bible, because the hunter is the messenger of heaven, and the hunting of animals can maintain a certain ecological balance. From this context, we can also derive the discipline of religious power on society, which in peter Handke's case is achieved precisely through the essence of the act of preaching, that is, language.

For Handke, language is an institution, which is very clearly reflected in his theatrical work Caspar. The work is based on the true story of Kasper Hauser, a legend in German history who knows where he came from, except that one day, this boy, who had been imprisoned in a dark, isolated room for 16 years, without any education, suddenly appeared on the streets of Nuremberg. At the age of 21, the boy was stabbed to death by unknown assassins. Some historians have speculated that he was related to the Grand Duchy of Baden, and others believe that he was just playing a trick, but these theories have never been confirmed.

Caspar's story provides excellent fodder for Western and especially German literature, and in Handke's version, Caspar is constantly learning human language, but this process also becomes a pure, unpolluted process of individual discipline and even self-destruction, and language becomes a tight suit on Casper's body, and the most common sentence he says in the play is, "I also want to be the kind of person that others once were." ”

Interestingly, six years after the premiere of Casper (1968), Werner Herzog, another of the four masters of the new German film, also filmed The Mystery of Caspar Hauser based on this person's background, precisely because there is no obvious reference between the two works, we can also see the similarities and differences between the two authors' interpretations of Caspar's character.

In fact, the human civilization faced by Kasper of Herzog was more complex and ambiguous: on the one hand he learned the human language, he was fascinated by human music, and for him language was not only a means of discipline, but also a way of understanding the world. But on the other hand, Casper also criticized certain extremely irrational institutional factors from a perspective that was almost external to human society, such as the tedious and meaningless religious ceremonies and aristocratic rituals of the time, and gradually changed from a plaything of the upper class to a frightening antisocial factor. As Brecht said of German society, "Discussing our current social form, or even the most insignificant part of it, will inevitably pose an immediate and complete threat to our social form", and in the film, these unscrupulous criticisms inadvertently uttered by Casper completely angered the conservative people of the time and eventually cost him his life. At the end of the film, the dead Casper is dissected, shouting that there is something wrong with his brain structure, and believing that his so-called "madness" comes from this "unusual" physiological condition. However, as outsiders in later generations, we all understand that the real problem is not in the physiological structure of the human body, but within institutions and civilizations and the limitations of human cognition. This is Herzog's profound questioning and ultimate critique of modernity, human reason, and even human civilization.

Although Peter Handke does not acknowledge that Casper is related to the Red Storm in France in 1968, it is clear that the work does reflect a certain symptom of the times, and is more closely related to the nature of modern society. Of course, Handke, with the help of Casper, explores not only the politics and society of the time, but also the eternal language, and he opposes the discipline of language on man, hoping to create the possibility of creating another kind of literature. From this point of view, handke's writing is more political and militant than a mere political essay, although this militancy and avant-garde were only recognized decades later by the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Great artists not only face the problems facing human society, but also must always face the problems faced by art itself, and the works of art they create must reflect the writer's efforts to correct confusion and deviation, and break the discipline of institutionalized literature on language.

It is undeniable that literary prizes themselves are part of this institutionalization, which is why writers like Peter Handke disdain to accept the Nobel Prize in Literature— he never wants to be another Caspar, a deplorable figure of his own, despite the influx of fame and fortune, which seems to be completely unavoidable. (Secretary of the Round Head)