Lee asks for it

In India, a new film about Kashmir has sparked a new round of ethnic hatred.

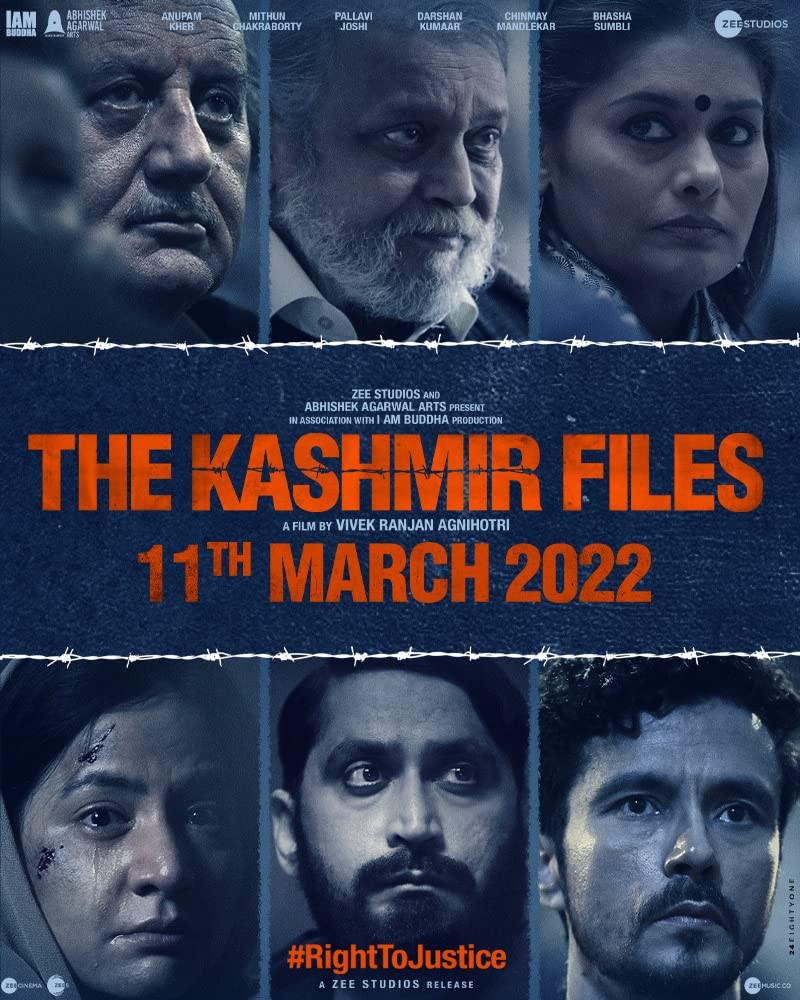

The commercial drama film, called The Kashmir Files, was planned for 2019 and funded by a subsidiary of India's private broadcast tv giant Zee Media Group, and entered theater release in early March 2022. In just one month, The Kashmir Archives became the highest-grossing Hindi film in India since the start of the pandemic. As of April 11, it had grossed more than 2.5 billion rupees (about 210 million yuan).

Poster of the Kashmir Archives

The film is controversial because it is highly consistent with the hate politics of the Modi government and the Hindu right it represents. Director Vivek Agnihotri chose Kashmir in the 1990s as the setting for the story, depicting the "genocide" of "Kashmiri Brahmins" through the film, as a pretext for India's subsequent hard-line policies towards Kashmir and the Hindu right-wing politics of the Modi era.

Although opposition parties, the left and many members of society have attacked the film for one-sidedly intercepting facts and inciting hatred. But unsurprisingly, after the film was released, Modi and many Hindu right-wing politicians inside and outside the ruling party immediately raised it to the level of "historical facts" and endorsed it. Modi himself has publicly stated that the film "truthfully reflects" violence against Kashmiri brahmins. At the end of March, yogi Attianath, the chief minister (governor) of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party and star of Hindu nationalist politics, received the film's main creative team. The Hindu monk governor said, "The film boldly reveals the inhuman catastrophe of religious fanaticism and terrorism. ”

In the past decade in power by the Modi government, India's central government has taken radical unilateral coercive measures against Indian-controlled Kashmir, which has not yet been attributed in a U.N. resolution. In August 2019, the Indian government repealed Article 370 of the Constitution by amending the Constitution. The article originally provided for Kashmir to have a special autonomous status. Subsequently, the Indian government split the former state of Jammu and Kashmir in two and cancelled local elections.

The abolition of Kashmir's autonomy and the complete incorporation of Indian-controlled Kashmir into India itself have been the consistent political goals of Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party and its parent organization, the National Volunteer Service Corps (RSS), for decades. The popularity of the Kashmir Archives is an extension of this Hindu right-wing political mobilization.

Constructing the "genocide" narrative in Kashmir

Agni Holti, the director of The Kashmir Archives, is a filmmaker with a strong political stance. He has said in numerous interviews that he opposes the former ruling Indian Congress party and Cold War-era socialist politics. In 2016, he directed the film Buddha in a Traffic Jam, which satirized and attacked India's Maoist revolution. He accused Indian academic intellectuals of being "urban Maoists," arguing that they and the communist guerrillas were "conspiring to overthrow the Indian government."

Agni Holty

In 2019, he launched the Tashkent Archives. The film revolves around the sudden death of India's second prime minister, Lal Bahadur Shastri. In 1966, after the outbreak of the Second Indo-Pakistani War over Kashmir, the Soviet Union brokered the signing of an armistice in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Just after the agreement was signed, Shastri died suddenly in the hotel. Agnihortti delved into history "on his own", arguing that behind the prime minister's death was a conspiracy to turn India into a foreign colony and a "socialist state."

The Tashkent Archives is the first installment of the director's "Modern Indian History Trilogy", and the second is the Kashmir Archives. He also plans to make another film in the future, The Delhi Archives, which is likely to be some kind of "reinterpretation" of the Sikh massacres of Hindus in Delhi in 1984.

In The Kashmiri Archives, the director arranges a story of a young man "discovering his identity": Krishna, a student at Nehru University, comes from a Kashmiri Brahmin family. Both of his parents died. He thought they had been killed in an accident. At Nitha, a prestigious school with a tradition of socialist student organizations, Krishna met his teacher Menon, who supported the Kashmiri movement for autonomy and struggle, and Krishna initially followed him. But Krishna slowly learned through friends and elders that his parents died at the hands of Muslim militants in Kashmir around 1990. Friends explained that militants in Kashmir had committed "genocide" against brahmin families like him. He eventually "woke up" and broke with his teachers on campus.

The "Kashmiri Brahmins" are the predominantly Hindu minority in the Muslim-majority Kashmir Valley region. India's founding prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, came from a Kashmiri Brahmin family. Before 1990, they accounted for 4 percent of the entire valley population — about 120,000 — in the entire valley region centered on the capital Srinagar. At that time, although there had been wars in Kashmir and local independence movements or pakistani movements, there was peace between brahmins and Muslims. With the outbreak of large-scale armed uprisings and violent attacks in the 1990s. In response to the dire security situation, from February to March 1990, more than 100,000 Kashmiri Brahmins moved out of the valley areas where they had lived for generations. According to statistics at the time, at least 32 Kashmiri Brahmins were killed in the conflict during this time.

The story was interpreted by the Hindu right as "the genocide of Hindus by Kashmiri Muslims". Before 1990, the international understanding of Kashmir was mainly the India-Pakistan conflict. Pakistan believes that India has adopted a very repressive rule over Indian-controlled Kashmir, and that the Indian military and police have arbitrarily arrested and killed local independence or joined pakistani movements. Thus, india's rule over Kashmir was morally passive.

By the 1990s, however, with unusually brutal and bloody massacres in Bosnia and Herzegovina in Europe (in Srebrenica) and Rwanda in Africa, the words "genocide" began to reappear. The Hindu right smells the power of the term. Represented by the pamphlet "Genocide By Hindus in Kashmir," published by right-wing peripheral organizations in the 1990s, Hindu nationalists began to use the kashmiri brahmins' escapes to construct a narrative of "genocide."

Looking back, Kashmir in the 1990s did see a large number of assassinations, raids and even small-scale mass killings. During this decade, there were two waves of armed resistance against India in the Indian-controlled Kashmir Valley. The first wave came from kashmir-based nationalists, the Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF), who attacked locals working with the Indian government; the other wave of religious militants influenced by Middle Eastern and Pakistani politics, led by the Jihadist Party (Hizbul Mujahideen), who launched numerous attacks on the military and police, but also clashed with local nationalists. In a decade, more than 30,000 Indian military police and militants have been killed. More civilians have died in military-police crackdowns or militant attacks.

But historical research points out that these killings and violence are not the same thing as "genocide." Indian scholar Sumantra Bose pointed out that because Kashmiri Brahmins account for a higher proportion of senior local government officials than they do in the general population, many Brahmin officials became victims in the 1990 assassination wave (such as the judge who sentenced the former leader of the Kashmiri Liberation Front to death in 1989), giving the impression that militants specifically targeted this group. But these assassinations were not based on race and ethnicity – local Muslim officials were the vast majority of the victims. However, in the countryside and in the suburbs, there were also attacks and killings against specific ethnic groups during this period. For example, in a massacre around Srinagar, 23 Kashmiri Brahmins were killed. However, it should be noted that the government military police and paramilitary forces at that time also committed many acts of collective killing. In 1993, for example, security forces killed 37 pro-independence activists in one go in Bijbehara, south of the valley. On the other hand, in the same year, some Brahmins who supported the Kashmiri Liberation Front, such as the left-wing intellectual Hriday Nath Wanchoo, were also assassinated, with the suspicion that these assassinations involved cross-border jihadist forces or the Indian security services.

On June 26, 2007, activists from the Jammu and Kashmir Salvation Movement (JKSM), a separatist party in Kashmir, burned a portrait of Anand Sharma, chairman of the hardline Hindu party Shiv Sena, during a protest in Srinagar.

The right tends to claim that Kashmiri Brahmins have all been "genocidated" out of the valley. But Baus's investigation in the mid-90s found that there were still a significant number of Brahmins in the Kashmir Valley region that had not been removed, and many had received help from Muslim neighbors. At the beginning of the new millennium, the local Brahmin community continued to organize religious ceremonies, sometimes with tens of thousands of participants. But despite this, the exodus of the Brahmins remains a huge stain and failure for the nationalist movement in Kashmir. This not only gives the right wing an opportunity to invoke the narrative of "genocide" to mask systematic, party-based and internationally game-based violence and killings, but also brings to the brink of bankruptcy the socialist-nationalist ideology that the Kashmiri Liberation Front has represented for more than half a century, emphasizing non-ethnic and religious beliefs, losing Kashmir's voice to the jihadist party and other forces heavily influenced by political Islam.

Historically, two resolutions adopted by the United Nations Security Council in 1948 and 1950 stipulated whether Kashmir would be incorporated into India or Pakistan in the future would be decided by a referendum on the ground. But for more than half a century, the implementation of these resolutions has become almost impossible. At the same time, the Kashmir issue in India is increasingly no longer the original issue of local nationalism, but has become a national identity political symbol of "Hindu vs Muslim".

The emphasis on "genocide" in the film Kashmir Archives is intended to continue to produce and expand this identity politics.

The film provokes ethnic violence

With Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party government coming to power in 2014, many of the agendas of Hindu nationalism have been greatly advanced. These include the abolition of Kashmir's autonomous status, push for the abolition of the Muslim Civil Code, and the rebuilding of the Hindu Rama Temple on the ruins of the Babri Mosque in Uttar Pradesh. In 2019, the Indian government introduced the National Status Act, which focuses on the national status of non-Hindus and foreign refugees. The Hindu right even began to recruit Muslim members, such as the National Volunteer Service Corps, which formed its own Muslim organization, Muslim Rashtriya Manch. According to research by Yale university scholar Felix Pal, some social elites and middle-class Muslims believe that Hinduization in India is inevitable and will choose to join Hindu right-wing organizations to seek asylum or more social resources.

In fact, it can be said that in Modi's Time India, the dominance of Hindu nationalist politics has been established, and the Muslim community with a population of over 100 million is no longer an "equal" minority under secularism, but is actually close to "second-class citizens".

However, the political mobilization of Hindu nationalism did not have the will to stop, but continued to expand the invocation of the politics of ethnic identity. The Indian media outlet The Wire did an interesting investigative report some time ago, and they found that the Kashmir Archives has become a mobilization symbol for the Hindu right-wing group. Many groups associated with the right-wing matrix, the National Volunteer Service Corps, have used the film online to post messages about Hindu nationalism.

For example, Deepak Singh Hindu and Vinod Sharma, who helped the Indian government appear in the 2020 Delhi Farmers' Protests, used the film to speak out. Deepak Singh Hindu said it was important to enforce uniform civil law, or Hindus would face a demographic cleansing. Sushil Tiwari, the leader of the right-wing Hindu Army, used the film's popularity to demand that Hindus take steps to reduce the fertility rate of Muslims (it is worth mentioning that the fertility rate in Kashmir is lower than in most Indian states). Others used the film to promote: "If Hindu men marry Muslim women (i.e., "transform" them into Hindus), we can reduce their population for the next three generations." ”

On December 21, 2020 local time, farmers protested in Delhi, India, and a large number of farmers gathered at the scene.

Various short videos have also been popular on the Internet through movies. One of the themes was the shouting of slogans in movie theaters – "Shoot those who betray the country!" ”(Desh ke gaddaro ko goli maaro saalon ko)。 The origin of this slogan was shouted by Kapil Mishra, one of the leaders of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, when the Modi government introduced the citizenship bill in 2020. The stigma of "betrayal of the state" predates — in 2015, Hindu nationalist student groups clashed with left-wing student groups supporting kashmir autonomy at Nehru University. Modi and his political forces took the opportunity to describe the left as "traitors" and have since vigorously purged nehru university management and student organizations.

Worryingly, as the Box Office of The Kashmir Archive continues to rise, the "revenge" mentality that its narrative instills in the public is getting stronger and stronger. In India, there are perennial bloody conflicts between right-wing ethnic groups and religious politics. In February 2020, during an ethnic clash in North Delhi, a group of Hindu mobs attacked the Muslim community, triggering a brawl that killed at least 36 Muslims and 15 Hindus. With the kashmiri archives and the intense anger fuelled by Hindu nationalism, a new wave of ethnic violence is brewing.

The Golden Age of Hindu Nationalism?

Although the Kashmir Archives has a ten-fold difference in revenue so far compared to the most successful box office film in Bollywood history, "Wrestling Daddy", such a film would not have received such high attention in the past few decades. Take the same director's 2019 Tashkent Archives, for example, when society at the time generally thought it was a bad film, all conspiracy theories.

The success of the Kashmir Archives means that after several years of strategy, Hindu nationalist politics has gained a foothold in the mainstream cultural industry. Compared to previous years of Bollywood Kashmir-themed films, such as 2014's Haider, the Kashmir Archive shifts the narrative axes from denunciation of politics against civilians to emphasis on individual and group revenge. More ambitiously, it also draws leftist intellectuals in India in for satire and trampling.

Poster of Haider

Some cultural observers have found that in recent years the Bollywood film industry has increasingly leaned towards the propaganda of the Modi government. Modi's government has been very friendly to business magnates in privatization and marketization, while the mogulists who run the cultural industries have invested heavily in films that align with government values — depicting border conflicts, military operations, and domestic counterterrorism. Traditionally, Bollywood films emphasize ethnic tolerance and mutual understanding, and in recent years there have been fewer and fewer secularist "mainstream narratives" of the Congress era.

And as geopolitics change in South Asia and around the world, the future initiative is in fact on the side of Hindu nationalists. After all, with the needs of the "Indo-Pacific policy" of the United States, India has more bargaining chips in the international environment in which it lives. The United States and the West have remained so silent on the Kashmir issue that it has been angrily criticized as "double standard" by former Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan. And in the future, this silence is likely to continue. One example is that U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris, of Indian descent, has been vehemently critical of Modi's Hindu nationalist politics. But after her election in September 2021, when she visited India and met with Modi, she had shifted her rhetoric to a joint "defense of democracy" between the two countries. On the other hand, concerns and moral support for Kashmir from Middle Eastern countries such as Iran or Turkey or Saudi Arabia are also waning. For India, the current situation is a "period of strategic opportunity" for Kashmir to "cook a mature meal". Even, in this context, the narrative of Hindu nationalism represented by the Kashmir Archives is expanding into international markets. Recently, director Agni Holti said that the film will break into the Israeli market and become a key step in entering the overseas market.

All of this reflects that with Modi's successive rulings, India has not only turned to the right politically as a whole, but has also moved significantly closer to the narrative of Hindu nationalism in terms of mass culture and even historical narrative. And this direction of development will hardly change in the future. As political power declines, India's intellectual and cultural industries, which support secularism or left-wing politics, are rapidly losing their ability to define agendas and promote discourse.

In contrast, Much of India's intellectual community is still immersed in the "defense" of the secularist Republic of India of the past. Their argument is that everything from Kashmir to domestic minority issues reflects the "lack of tolerance" of the Hindu nationalist state. On the right, however, the question is not about inclusion or non-inclusion, but about how to mobilize society – through film, culture, politics. Ultimately, they want to radically transform India in all directions – both politically economically and culturally – in order to radically change the definition of the country itself since independence in 1947.

Editor-in-Charge: Wu Qin