Coca-Cola propaganda poster during World War II

01 19th century British obsessed with sugar and tea in pursuit of status?

In my 1985 book Sweetness and Power, I made the argument that advocating large-scale enjoyment of tea, sugar, tobacco, and a few other things was typical of the consumption habits of the 18th-century British working class, and probably the first example of the collective consumption of imported food by the masses. In that book, I tried to show what special appeal those novel foods had for those new consumer groups.

Recently, two historians have tried to take a new perspective, deciding that the "real" reason should be the "pursuit of status." Identity may sound concrete and clear at first glance, but if you add Norbert Elias's research into the other side, it only reveals half the mystery. We still don't really understand the truth, for example, why so many British people are so easy to become a consumer of tea and sugar. The so-called "status" may exhaust many traits, such as hospitality, generosity, proper manners, rigor, social competitiveness, and other traits. If our purpose is to explain what special influence a particular food (or even a certain type of food) has on consciousness and will, then the unanswered (and perhaps unanswerable) question remains.

19th century English afternoon tea

I have pointed out in the past that the british consumption of sugar includes the following factors: first, tea and other emerging beverages, such as coffee and cocoa, contain powerful stimulants, and these drinks are sugared; second, the British working class at that time had malnutrition problems, so high-calorie sugar, so people actively or unconsciously like it; third, human beings are obviously generally born with a preference for sweetness; fourth, if the situation permits, in most (if not all) of society, People always want to imitate the life of high society; fifth, "novelty" itself may have its influence; sixth, tobacco and drinks with an excitatory effect help to soothe the tired industrial life. Faced with this exuberant list, it is difficult to sort out the relationship between the specific food of society and the operation of influence.

The British began to drink sugar and tea during the country's overseas expansion and colony seizures, when the African slave trade was booming and the number of colonial farms was increasing. In the United Kingdom, the degree of social industrialization, rural exodus and urbanization is increasing. Sugar, in its early years, was a rare and precious imported medicine and condiment, and by this time it was no longer expensive (the price first plummeted and then continued to fall); however, the price of sugar, despite the decline, was multiplied in use. The easier it is for people to get sugar, the more occasions they use it.

Once even the most meager earners could afford to eat sugar, its use exploded. So sugar entered the realm of everyday life, especially with tea, coffee, and cocoa, three refreshing drinks (in Britain, tea soon took the lead).

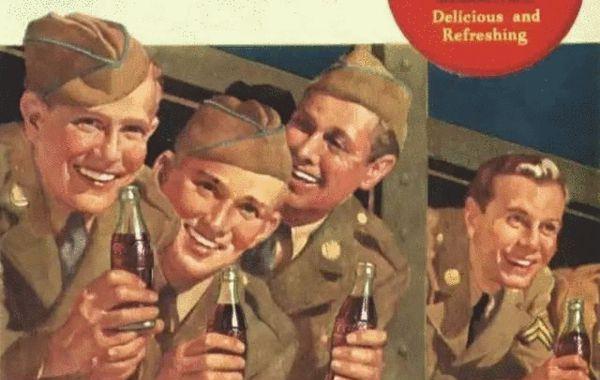

02 Fight for Coca-Cola: World War II made soft drinks in the Southern United States popular all over the world?

In human history, the method of changing eating habits has been the most effective in war, and in wartime, civilians and soldiers have been included in the jurisdiction of the military - this is especially true in modern times. Food resources, as well as other resources, are uniformly allocated by the government. The army is supported by the stomach; therefore, the general, who is also an economist and nutritionist at this time, decides what to feed Brother Abing. That was what they had to do, but it also depended on the economic power of the state and those who sustained the economy to meet the general's demands. During World War II, more than fifteen million Americans were conscripted into the army, and millions more were supported in the rear. The service members all dined together in the big restaurant. They can only eat the dishes made by the gang room; and the person in power who decides what to cook in the gang room is not a person in the army, and has never experienced the suffering of the army.

American soldiers carrying Coca-Cola during World War II

Those who served in the military enjoyed a number of benefits, one of which was meat to eat for twenty-one meals a week, and even an extra meat dish to choose from on Fridays (usually sliced cold meat). Most soldiers had never eaten so much meat before (of course, meat was not so regular during combat). Soldiers also had access to a large number of coffees and various desserts; there were sugar cans at each table, and two meals a day were served dessert at the end, without exception. (In fact, when Brother A bing queues up to receive his salary every month, there is no limit to the supply of cigarettes.) Although the food preferences of civilians have not changed so much, they have changed slightly, and everyone probably already knows this. Because meat was so rare for civilians, the wartime media was filled with stories and jokes about hooking up with butcher shop owners. In addition, sugar, coffee, and cigarettes are also quite rare. As a result, their food preferences inevitably change dramatically. Since then, North Americans have developed new food preferences due to the war (in fact, this "bias" is actually biased, because it is forced by the situation).

One thing, whether military or civilian, is not in the ration, is Coca-Cola; but in order to make it available to everyone, some people have worked hard to make it available. During World War II, George Catlett Marshall, the chief of staff of the U.S. Army, was a Southerner. Shortly after Pearl Harbor, General Marshall informed all the generals to ask the government to add a Coca-Cola production plant so that products could be supplied to the front. Affected by Marshall's move, Coca-Cola enjoyed the same economic status as food and weapons during the war, and thus did not have to be limited by sugar rations. A total of 64 Coca-Cola production plants have been established in the Allied Theater of Operations in the Pacific Theater, the North African Theater, Australia and other regions. At the request of the armed forces, coca-cola sent technicians to take charge of cola production, sending a total of 148 technicians, 3 of whom were even killed in war zones.

Although Coca-Cola was beautiful after the end of the Second World War, it is worth mentioning that before the war, let alone a trademark with a head and a face in the world, it may not be a household name in the United States. Although the company had exported to Cuba in the early years, Coca-Cola was basically a domestic beverage in the United States, and the actual situation at that time was probably that no one except southerners would drink Coca-Cola without ingredients. In addition, during World War II, most of the professional officers of the US military were Southerners, which should also be an important factor in the rise of Coca-Cola.

How the "external" meaning has made Coca-Cola popular around the world is not difficult to see. Coca-Cola's extensive production plants in the Allied theaters have a lot to do with its growing popularity. In times like these, state power itself, in the eyes of united Americans, is clearly less obnoxious. The allocation of food production resources is also related to the choice of consumers. However, in this case, 95 percent of the non-alcoholic beverages sold at the US military base were Coca-Cola products. There is a choice, but it is up to one company to decide the range of options.

The symbolism associated with Coca-Cola, such as the national momentum established during the War, is truly impressive. At that time, the soldiers who served overseas were not only deprived of all the things that displayed their personal characteristics (such as clothing, jewelry, hairstyles), but also because they were in a distant foreign land, they could not see the substance that represented their culture. In this environment, it can make people feel more lonely, and if there is something that can fill this cultural gap, such as food or drink, this thing has additional potential power. Coca-Cola happens to be a treasure trove of near-perfect symbolism. In the home letters sent back home by servicemen who served overseas, it was often written that they were fighting for the right to drink Coca-Cola. The "intrinsic" meaning of Coca-Cola is clearly revealed in the mood of these soldiers, who fought and did other things "to protect the custom of drinking Coca-Cola and to protect the thousands of well-beings that the state brings to its people" — a true passage about Coca-Cola found during the inspection of letters during the war. In this way, Coca-Cola became a symbol in the hearts of young warriors in the 1940s — a symbol that truly represented the country.

03 Is haute cuisine one of the ways in which a certain class expresses its prerogatives?

We have to leave some space for another difference in eating behavior in society, which has nothing to do with locality in origin and nature, but is a sign between different groups. In the case of the United States, of course, we think of class: some eat Philip tender beef loin, some eat cheap neck and shoulder areas; some eat caviar, some eat cod; some drink a few dollars a bottle of red wine, some drink Lafite Rothschild's expensive wine; and even distinguish between fast food shops and French restaurants! Mary McCarthy once compared American eating behavior with that of Europeans and found a striking difference, which is that everyone eats the same thing among Europeans regardless of class. In Europe, she said, different classes of people love different amounts of food, but regardless of whether they are expensive or poor, the food itself is about the same. Looking at the situation in the United States, she believes that people of different classes really eat different foods.

Song Dynasty banquets

Sometimes people use "dish" to refer to "high-end cuisine", like the Chinese cuisine expert I will mention below: Michael Freeman. Freeman lists four elements of the dish. But just read his article and you'll immediately understand that he's talking about "haute cuisine":

The emergence of (high-end) "dishes" includes the following factors: easy access to raw materials, many picky consumers, chefs who are not bound by conventions and religious rituals, and people who go down to restaurants. In China under the Zhao dynasty (960-1279 AD), agriculture and commerce coincidentally flourished together, which was associated with political events, accompanied by a change in attitudes towards food.

During the Song Dynasty, an important (and perhaps decisive) factor in the development of Chinese cuisine was the agricultural changes that took place at that time. Such changes are important first and foremost because they increase the overall food supply.

Freimann mentions (1) ingredients; (2) and (3) consumers and chefs – two distinct groups that are not related to the local food sub-system– and (4) there has been a fundamental shift in people's attitudes toward food, which Freuds sees as the four fundamental factors in the emergence of a high-end dish.

If one way of eating is seen as "lower level" than the other, then a class system arises. Therefore, when we compare high-class dishes or luxurious dishes with the foods that people usually eat in that society, we think that they belong to a certain class or privileged group. When people talk about North American food, they don't think that Texas-Mexican cuisine is high-end and Boston cuisine is vulgar, and vice versa. But they must know what is exquisite and what is ordinary. We may also compare different periods of the same society, including when high-end dishes were produced or lost. We can say that China once had high-end cuisine (many people think that most of them are now only in its Taiwan and Hong Kong regions). However, if we say that there are still high-end dishes in China, we obviously do not mean the kind of dishes that every Chinese eats.

In what way does a class or privileged group express its status? The "dishes cooked and presented" – nightingale tongue and caviar – are sometimes consolidated by limiting the power of consumption (only kings, royals and nobles can eat them, as well as swans and sturgeon). "Seasonal products by supply"—the first fruits plucked, the best in season, the last one left—are sometimes reprocessed to add flavor, such as salting, air-drying, candy, distillation, etc. [so pears can be made into syrup-stained pears, called eau de poire or Poire William; frosted pears, pear dew, pear jam – the process of making these foods increases the value of the food). "By cooking" – how many man-hours and how much technology each bite of food takes before it is delivered into the mouth (the two are usually related to each other). And "through the use of special raw materials" – produced only in one place and not completely replaced. It is the same as the lotte but is by no means the same; farmed salmon is different from wild salmon; there is no flounder comparable to dover's flounder, and so on. Local products are repeatedly absorbed into high-end dishes, but always at great expense.

Although Freiman believes that abundance and variety are essential to sustain (high-grade) dishes, quantity alone is not enough to produce (high-grade) dishes. It's not just a matter of quantity. Nor is the dish just about "how to cook", but not just a little more explanation: "A dish is certainly not just the 'way or style of cooking' as defined in the dictionary; we really can't imagine something like a 'fast food dish'". Haute cuisine is also not just table towels, porcelain, full tableware, the order in which it is served, the length of time each dish is used or the whole meal, the furnishings, the row of seats, the etiquette – although these elements, or similarities, are often the hallmarks of the dish.

In human nature, there may not be a need for food diversity, but this desire always feels quite common. One of Freeman's claims seems particularly interesting: "The dish is the product of an attitude toward food, of putting the pleasures of eating first, not for the purely ritualistic purposes of it." This view is thought-provoking, because At this point, Freeman seems to have regressed to the level where haute cuisine first arose. Such a view does not seem to have to consider the level of hierarchy, nor the attitude of which societies have a good attitude towards food, and which societies do not. In other words, it means that haute cuisine (food of a privileged class) comes from a broader range of food values, an attitude held by many people (and perhaps even most) people in society as a whole.

Freeman noted that the technological achievements of the Chinese Song Dynasty in agriculture increased the absolute total supply of certain foods at that time, increased the variability of food, and significantly increased the types of food available to civilians: new varieties of rice, lychees, fresh fish, etc. Tea and sugar are also commonly consumed. These achievements are not necessarily related to the refinement of elite cuisine, nor to the general increase in food sources throughout civilization. They are neither the same thing nor mutually exclusive as the development of haute cuisine. In France, the attitude and cooking habits of the "common people" are the authentic dishes, and the situation in China is similar, you can see a unique culture, on the one hand, the food is valued by all people, and on the other hand, there are high-class dishes that only the elite class can enjoy. For example, Chinese banquets do not eat white rice, which clearly means that this is a banquet. However, there is an incredible consistency between the conventional food supply methods and the relationship between the standardization of the food, the order of serving, and the guests from the top to the bottom. Such conventions seem to transcend regional and social classes, and indicate that their occurrence may predate the rise of high-end cuisine. I think that it is only through this method that the social basis for the unique cuisine of a country can be established.

I would like to return to Freeman's view that "the dish is the product of an attitude toward food, a matter of putting the pleasures of eating first, not for the sake of purely ritual purposes." Putting the real pleasure of eating first, I think, is tantamount to saying that it is widely believed that the "real pleasure of eating" is the foundation of all dishes, not just high-end dishes. If the true pleasure of eating is the most important thing for diners, then at least in part the general perception of food must exist before high-end dishes are produced. Admittedly, this view is unanswered about how the cuisine relates to high-end dishes. But I suspect that Freimann's main view, the "decisive" factor in the Case of China, is that there has been a significant increase in the availability and change of food, which must be accompanied by an equally decisive universal "value," namely, "the view of food as a source of sensual pleasure." Do we dare to say that the vast majority of civilians in Italy, France, Turkey, China, etc., would still have high-end cuisine in these regions without first giving the real pleasure of eating without first giving them the "primacy"? I don't think we dare.

Only three to four conclusions need to be made here. "Nationally endemic dishes" is a paradox; for there may be local dishes but there will be no national dishes. I think that, in general, the so-called nationally specific dish is a generalization, sweeping away the food eaten by a group of people living in a political system. To be more precisely defined, "cuisine" must involve eating habits passed down from generation to generation in a region, where people actively exchange views on food, so that the shared concept of cooking and the stable production of thematic foods can continue. High-end dishes, although so called, the content is a collection of foods, styles, and dishes in some regions, and then purified as a result, selecting the most distinctive dishes and a wide range of representative characteristics from each region to create a country-specific dish. Haute cuisine differs from dishes in that the former represents more than one region, replaces the original with expensive materials, and sometimes even gains international status. Like it or not, it's "restaurant food" that only appears in restaurants abroad or in big cities.

In cultures that value food, a strong interest in food taste probably predates local dishes. At the local level, this interest not only goes beyond ordinary foods such as bread, macaroni, and vegetables, but also adheres to the concepts widely held and understood by local representative dishes. This, in my opinion, is the true meaning of the dish.

(Thanks to the Electronic Industry Press, Sanhui Books for providing text)

| about the | of the book

By Sidney W. Mintz

Publisher: Sanhui Books/Electronic Industry Press

Subtitle: Ramblings about the power and influence of food

原作名: Tasting Food, Tasting Freedom. Excursions into Eating, Culture, and the Past

Translator: Lin Weizheng

Publication year: 2015-8