Machine Heart report

Edit: Egg sauce

As researchers continue to flood into the "new world" of advanced AI chatbots, publishers like Nature need to acknowledge their legitimate uses and set clear guidelines to avoid abuse.

For several years now, AI is gaining the ability to generate fluent language, beginning to mass-produce sentences that are increasingly difficult to distinguish from human-generated text. Some scientists have long used chatbots as research assistants to help organize their thinking, generate feedback on their work, assist in writing code, and abstract research literature.

But the AI chatbot ChatGPT, released in November 2022, officially brought this tool capability known as a large language model to the public. Its R&D arm, San Francisco-based startup OpenAI, offers free access to the chatbot, which can be easily used even by people without technical expertise.

Millions of people are using it, and the results are sometimes fun and sometimes scary. The explosive growth of "AI writing experiments" has made people increasingly excited and uneasy about these tools.

The joys and sorrows of ChatGPT's superpowers

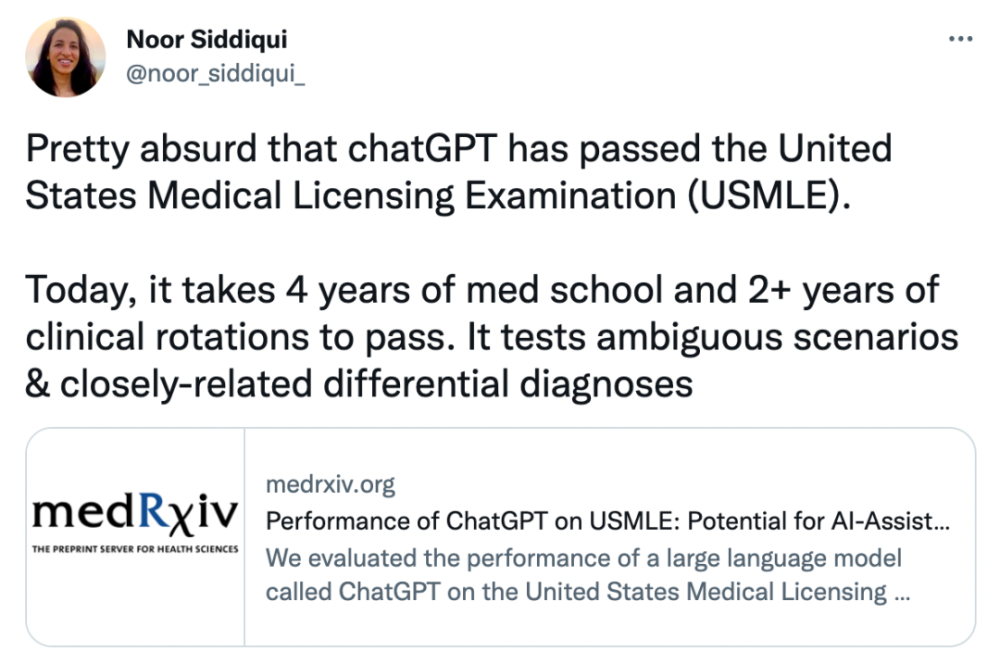

ChatGPT can write beautiful student essays, summarize research papers, answer questions, generate usable computer code, and even pass medical exams, MBA exams, bar exams, etc.

Some time ago, ChatGPT was "close" to passing the U.S. Medical License Examination (USMLE) in an experiment. Generally, it takes four years of medical school study and more than two years of clinical experience to pass.

Step 1 is taken after 2 years of study at medical school and includes basic science, pharmacology, and pathophysiology. Students study an average of more than 300 hours to pass.

Step 2 is conducted after 4 years + 1.5-2 years of clinical experience in medical school, including clinical inference and medical management.

Step 3 is attended by physicians who have completed 0.5-1 years of graduate medical education.

ChatGPT also successfully passed Wharton's MBA Operations Management final exam. Of course, this kind of exam is not the hardest question, but it must be considered "breakthrough" to complete in 1 second.

In the matter of bar exams, ChatGPT still shows extraordinary ability. In the United States, in order to take the bar professional license exam, most jurisdictions require applicants to complete at least seven years of postsecondary education, including three years at an accredited law school. In addition, most test takers go through weeks to months of exam preparation. Despite the significant investment of time and money, about 20% of test takers still score below the requirements to pass the exam on the first exam.

But in a recent study, researchers found that for optimal prompts and parameters, ChatGPT achieved an average accuracy rate of 50.3% on the full NCBE MBE practice exam, significantly exceeding the baseline guessing rate of 25%, and achieving an average pass rate in both evidence and infringement. ChatGPT's answer ranking is also highly correlated with accuracy rate; Its Top 2 and Top 3 choices have 71% and 88% correctness rates, respectively. According to the authors, these results strongly suggest that large language models will pass the MBE portion of the bar exam in the near future.

The level of research abstracts written by ChatGPT is also so high that scientists find it difficult to detect that these abstracts are written by computers. Conversely, ChatGPT may also make spam, ransomware, and other malicious output more vulnerable to society as a whole.

So far, the content generated by language models cannot be completely guaranteed to be correct, and even in some professional fields, the error rate is high. Without the ability to distinguish between human-written content and AI model-generated content, humans face serious problems of being misled by AI. Although OpenAI has tried to set limits on the chatbot's behavior, users have found ways to circumvent the restrictions.

Academic concerns

The biggest concern of the academic research community is that students and scientists can fraudulently treat the text written by large models as their own, or use large models in simplistic ways (such as conducting incomplete literature reviews) to generate some unreliable work.

In a recent study by Catherine Gao et al. at Northwestern University, researchers took manual research papers published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), the British Medical Journal (BMJ), The Lancet, and Nature Medicine, used ChatGPT to generate abstracts for the papers, and then tested whether reviewers could find that the abstracts were AI-generated.

The experimental results showed that reviewers correctly identified only 68% of the generated abstracts and 86% of the original abstracts. They incorrectly identified 32% of the generated digests as raw and 14% as AI-generated. "It is surprisingly difficult to distinguish between the two, and the resulting abstract is vague and gives a formulaic feel," the reviewer said.

There are even preprints and published articles that have given official authorship to ChatGPT. Some academic conferences have been the first to publicly object, such as the machine learning conference ICML, which said: "ChatGPT is trained on public data, which is usually collected without consent, which brings a series of accountability problems."

So perhaps it's time for researchers and publishers to set ground rules for the ethical use of large language models. Nature publicly states that two principles have been developed in conjunction with all Springer Nature journals and have been added to existing author guidelines:

First, any large language modeling tool will not be accepted as a byline author of a research paper. This is because the attribution of any author comes with responsibility for the work, and AI tools cannot assume that responsibility.

Second, researchers using large language model tools should document this use in the Methods or Acknowledgements section. If the paper does not include these sections, the use of large language models can be documented with an introduction or other appropriate section.

Author's Guide: https://www.nature.com/nature/for-authors/initial-submission

The corresponding author should be marked with an asterisk. Large Language Models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT, do not currently meet our authorship criteria. It is worth noting that the author's attribution comes with responsibility for the work, which cannot effectively apply to LLM. The use of LLM should be properly documented in the method section of the manuscript (or in the appropriate alternative section if there is no method section).

It is understood that other scientific publishers may take a similar stance. "We do not allow AI to be listed as authors of our published papers, and using AI-generated text without proper citations may be considered plagiarism," says Holden Horp, editor-in-chief of the Science series.

Why are these rules in place?

Can editors and publishers detect text generated by large language models? Now, the answer is "maybe." If examined closely, the raw output of ChatGPT can be identified, especially when there are more than a few paragraphs involved and the subject matter involves scientific work. This is because large language models generate lexical patterns based on their training data and the statistical correlations they see in prompts, which means that their output may look very bland or contain simple errors. In addition, they cannot yet cite sources to record their output.

But in the future, AI researchers may be able to solve these problems — for example, there are already experiments linking chatbots to tools that reference resources, and still others training chatbots with specialized scientific text.

Some tools claim to detect output generated by large language models, and Springer Nature, publisher of Nature, was one of the teams developing the technology. But large language models will improve rapidly. The creators of these models want to be able to watermark the output of their tools in some way, although this may not technically be foolproof.

A recent popular paper on adding "watermarks" to the output of large language models. Address: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2301.10226v1.pdf

From the earliest days, "science" has advocated transparency about methods and evidence, regardless of the technology that was popular at the time. Researchers should ask themselves how the transparency and credibility on which the process of generating knowledge depends can be maintained if the software they or their colleagues use works in a way that is simply not transparent.

That's why Nature has developed these principles: Ultimately, research methods must be transparent and authors must be honest and truthful. After all, this is the basis on which science is based.