Adams: The Birth of 40 Works Part VIII

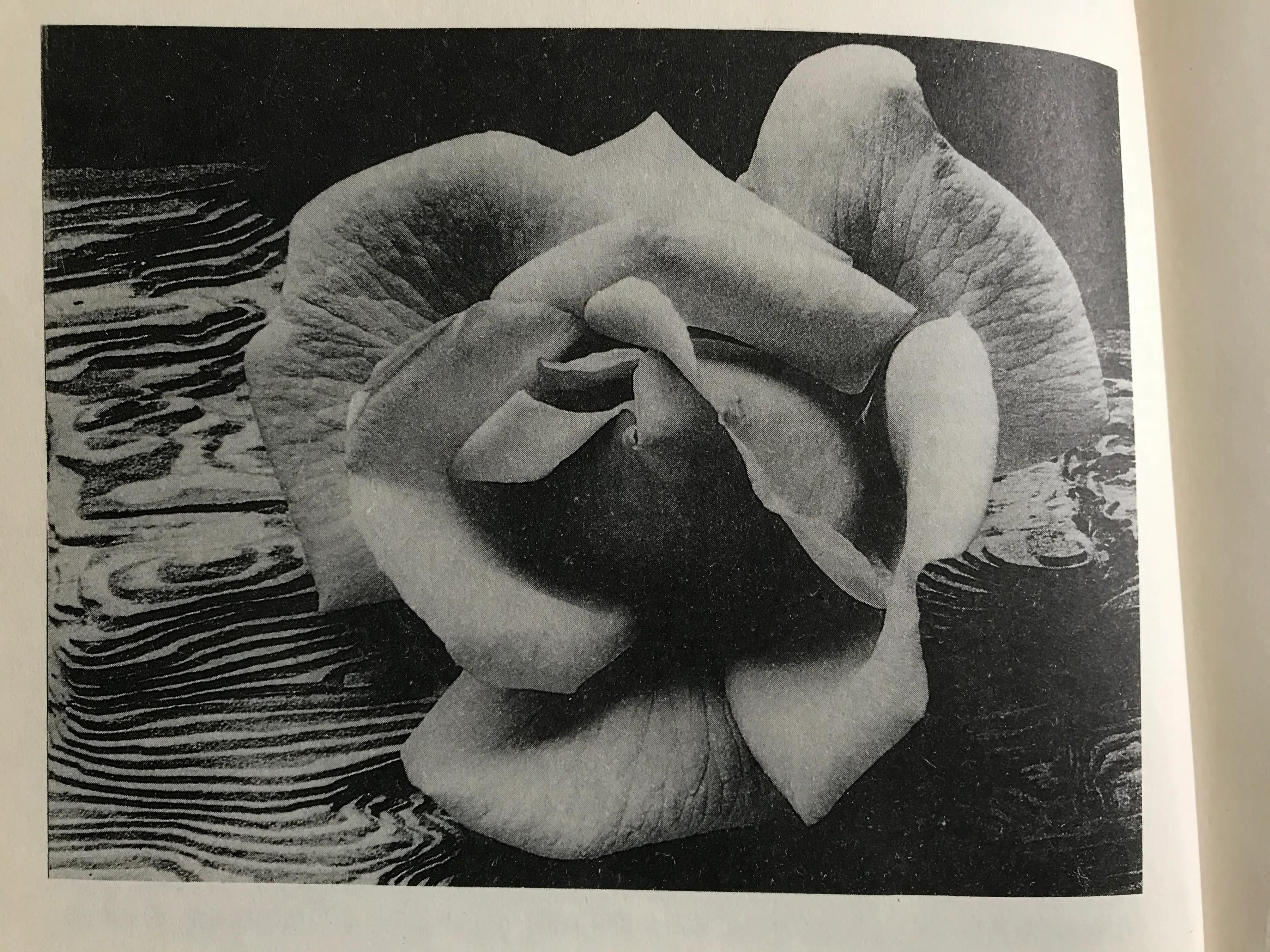

Roses and driftwood

Roses and driftwood

(San Francisco around 1932)

My home is in San Francisco. In my house there is a room with windows facing north that provides good lighting, especially in foggy weather. My mother plucked a large pink rose from the garden and proudly gave it to me. I immediately thought of photographing the flowers. For translucent rose petals, the light from the north side of the window is ideal, but I can't find the right background. I experimented with anything I could find—large bowls, pillows, neatly stacked books, and so on—but none of them were satisfactory. I finally remembered that I had a piece of wind-blown plywood, an old plank fished out of the sea near Baker Beach. I placed two pillows on the table, put wooden planks on top of them, cushioned them to a suitable height under the window, and then placed the roses on top. The pattern on the board against the shape of the petals is very coordinated, and I completed this photo in time.

I used a large 4×5-inch camera, an 8-inch Zeiss kodak desorption lens. This is one of the lenses I used in the early days. I remember using ASA50 Kodak film. I admit that I took 6 shots of different grades with "bracket exposure"; One of them was very successful! I was close to flowers when I was shooting, and I ended up having problems with depth of field. In order to get the best negatives, I used the smallest aperture on the lens, F/45, and the exposure time was about 5 seconds. At that time, I did not understand the effect of the law of inversion.

The initial image is quite soft, but the shadows on the negatives are too thin. I could more or less imagine an image, but at the time I didn't know basic exposure and development control. A few years later, when I occasionally took this negative to make a photo, I printed a photo with a richer light and dark layer. The first photo is of Givanovo Brom photo paper. The recently produced photo uses Oriental Seagull No. 2 photo paper, with selenium toner toning tones.

Someone once asked me what prompted me to take this picture. At that time, it was widely believed that every photograph should be related to an example represented in another art form. I also never thought that one photo might be influenced by another. Of course I have seen flower paintings, but as far as I can recall, I have never seen a painting of a large flower alone. I certainly haven't seen Georgia O'Keefe's large-scale, graceful paintings of flowers in all its forms. After reminiscing, I think this photo is the product of my personal inspiration, without any work inspiration and has nothing to do with the art I know. It is nothing more than a beautiful subject with a harmonious background and comfortable light.

This is undoubtedly a subject that has been manipulated. I have no doubt about this arrangement or manipulation, although it does not fall under what I later consecrated as "the subject of the discovery.".

There is a big difference between a spotted subject and a subject at the mercy of a subject. A discovered subject is something that exists objectively and is discovered by a photographer. In the complex world around us, we often find something or something that stirs up our imagination. For me, this is one of the most frequent direct reactions; The more I tried to look for something important to photograph, the less likely I was to find something meaningful.

The subjects that have been manipulated need to be selectively organized and arranged, while the captured subjects need to be found analytically and thoughtfully. Of course, imagining an image is a rapid response of the brain, but it needs to take into account the viewpoint, the focal length of the lens, exposure and development program, etc., in order to achieve the desired effect.

The manipulated subject is not saying there is something wrong; Most of the various works taken in the studio are well-designed and arranged photographs, and some of them are very beautiful. When I take pictures in the studio, I design and arrange the subjects as if they were stage sets. In addition to the camera, I have to carefully arrange the shapes, shades and contrasts, lights, backgrounds, etc. The camera and the entire arrangement process are then used to record the humanly modified subject. Dealing with the subjects that are discovered is completely different, requiring brains and emotional experiences. Edward Weston, in his sensitive and persistent pursuits, carefully arranged the shells and green peppers to form a vivid composition, and no one doubted their beauty. He must have continued to work on "indoor shooting tasks", and the effect was the same in terms of appeal as the large-scale vistas he took while working outdoors, partial close-ups of natural scenes, and cross-sections.

We actually often observe some objects up close. Because we walk on the ground, we generally observe the objective things around us at a distance of about two meters. If we are riding on a horse or sitting in a car, then we are some distance away from the environment around us. The "landscapes" we observe and photograph; Our vast world has been inappropriately described as a "landscape." The things we are most familiar with and see every day are generally pages of books printed in printed form. Small and mundane things tend to be rarely explored.

With the exception of taking a few scientific photographs, the camera rarely takes into account a few things close to us. In his book Art Forms in Nature, Blosfeld reveals a new perspective on vision. Arget Lunger – Pachak, Cunningham, Worth, Strand, Edward, and Brett Weston – all observe the world up close; Their cameras were once aimed at the hitherto overlooked universe. The microscopic world (the world that human vision cannot see) has another special image, but the microscopic world seems to be the most suitable for lens and creative expression.

Most of the photographs I took before 1930 were not very fascinating, but when I mastered the inherent properties of cameras, lenses, filters, and exposures, I was free to observe the whole landscape around us with a keener eye, a landscape that included scissors and threads, sand grains, the texture of leaves, the human face, and a single rose.

My meeting with Paul Strand and the development of the F/64 group led me to consciously consider the artistic component in my selection, observation and filming. If I hadn't met Strand and Stiglitz and joined the F/64 team, I don't know what my work would have looked like. It was the influence of The Strand and the F/64 group that made me decide to switch from music to photography, or I might have continued to be a musician. We can never know that some of the big choices in our lives might take us there.

Ansel Adams

"We don't just take pictures with our cameras, we take to photography all the books we've read, the movies we've seen, the music we've heard, the people we've loved."

—Ansel Adams